Coming 2 America was a long journey. It took Eddie Murphy more than three decades to make the sequel to his 1988 comedy classic. By late 2019, filming was complete and its studio, Paramount Pictures, expected a Christmas 2020 release.

Then COVID struck.

Technically, releasing an expected blockbuster during a global pandemic is called bad timing. Cities were in lock-down. Theaters were shuttered. The much-awaited feature was in limbo.

Then Paramount flipped the script by selling global distribution rights to Amazon for $125 million. That netted Paramount a tidy $65 million profit and let others worry about how the show would go on. Jeff Bezos figured it out. Amazon promptly pulled the plug on theatrical release and announced a March 5, 2021, posting of Coming 2 America on its Amazon Prime video service. The blockbuster would be downloaded by Prime members, in 240 countries, free of charge.

The maneuver shook the entertainment world. Sending a studio’s potential mega-hit straight to streaming puts hundreds of millions of dollars in box office revenues at risk.

Politically, it was even more dicey. The idea of a movie owner, Amazon, yanking its film from independently owned theaters and exclusively offering the film to audiences via a unique retail platform it owns was considered highly suspicious — if not outright illegal — under the 1948 Supreme Court decision in U.S. v. Paramount Pictures and subsequent Justice Department consent decrees. That verdict sought to limit a movie’s “chain of production” — separating production and distribution from exhibition — ostensibly to foster competition. Amazon spit in the eye of that theory with Coming 2 America and is now tripling down as it seeks to buy major film studio MGM, one of the original Paramount defendants.

To appreciate all of this, we need to review the history of video entertainment in America: how the “big” studios of the Paramount decision were once entertainment industry outsiders, how they formed their own theater networks to exhibit then-novel feature films, how those networks were deemed anti-competitive by the courts, and then how new technologies — television, cable, and the internet — came along and upset everything.

Competition in the Talkies

The Paramount courts banned many practices then used by the eight corporate defendants to book movies into cinemas and mandated that the five vertically integrated studios (Fox, MGM, Paramount, RKO, and Warner Brothers) divest their theater chains. Although criticism of the economic arguments underlying the decisions has mushroomed over the years — culminating in the rescinding of the Paramount consent decrees in 2020 — some contemporary analysts nonetheless tout the Paramount opinion as the zenith in enlightened antitrust.

In fact, the policy flopped on its own terms, as movie production plummeted and theater ticket prices soared in the years following the decision. The first outcome may be explained by the coincident emergence of broadcast television, but the rise in theater pricing cannot. It is also curious that television failed to boost movie production under Paramount: a tremendously popular new means for video distribution should, all else equal, enrich studios.

In any event, the legal result was an economic embarrassment. As Brookings Institution economist Robert Crandall wrote in 2019:

The fascinating aspect of the Paramount divestiture decrees was their timing. The government forced the motion picture companies to divest their theater chains just as home television was beginning to take over…. Thus, the government forced the distributors to unload assets whose values would soon decline rapidly!

Crandall thus highlights the importance of new technologies, shifting organizational forms, and the entry of new competitors — something Paramount prosecutors failed to appreciate. It was an ironic oversight, given that years earlier the Paramount defendants had themselves been the Davids rather than the Goliaths, small but scrappy start-ups battling an entrenched behemoth.

In the early 20th century, a trust known as the Motion Pictures Patent Company (MPPC) sought to control all U.S. movie production via a patent pool. The MPPC owned rights to cameras, projectors, and film — Thomas Edison being the organizer and the Eastman Kodak Co. a member. The Edison Trust’s brightest buzz occurred in 1909 when it held theater owners to onerous terms, dictated severe limits on formats (5- and 10-minute “shorts” only), and blocked rival filmmakers by aggressively suing for infringement on their patents.

Against this technological powerhouse, a ragtag squad of theater owners dissolved the cartel bottleneck like battery acid on a croissant. Adolph Zukor (who led Paramount), Carl Laemmle (Universal), and William Fox (what became 20th Century Fox) integrated their nickelodeons into film distributors, and then creators, of films. They sought to serve their working-class patrons with full-length scripted motion pictures telling dramatic stories. This differed from the MPPC’s offering of short films displayed as high-tech novelties, followed by live vaudeville performers — a programming strategy that proved comical in hindsight. To compete, the upstarts first imported original content from European markets (silent films featured no language barrier), then built their own studios in Hollywood (where subpoenas from Trust lawyers had more trouble landing on their subjects, plus the weather was better), and then destroyed the Trust’s patent claims in court. By 1918, the Edison Trust was kaput.

Fear of Vertical Video

By the 1920s, the daring outsiders were driving an exciting new industry, introducing wildly popular products. They soon transitioned to “talkies” that could deliver mass market entertainment previously available, via live concerts and legitimate theater, only to elites. The pioneering firms that led this revolution innovated in both filmmaking and exhibitions.

Their entrepreneurial success led to regulatory backlash. Paramount asserted that vertical integration was an inherent threat to rivalry. Big studios might kneecap competitors by combining with theaters. The links could be outright ownership (vertical integration) or via marketing arrangements (such as block booking, which sold cinemas bundles of films rather than each feature separately). Let Paramount or Warner Brothers control theaters, said the authorities, and they would save their most popular flicks for themselves, killing independent movie houses. And the reverse: they would run even their duds, filling screens and leaving indie film producers without audiences.

How promoting bad pictures, while limiting the viewership of hits, would prove profitable was not well specified. Indeed, had the posited foreclosure actually occurred, its most likely result would have been to throw the excluded victims — cinemas seeking films and producers seeking theaters — together. In actual practice, the Paramount defendants widely showed their films in independently owned venues and exhibited many independent films on their screens.

The 1948 Paramount decision proved a failure. Between 1947 and 1962, the number of independent theaters fell by more than 1,100 while the number controlled by large chains increased by nearly twice that. Whereas independent exhibitors had accounted for nearly two-thirds of all cinemas in 1947, they accounted for just one-third (of a much smaller universe) 15 years later.

Over the Top

Today, artists and entrepreneurs are embracing the forms of integration that had once brought success to the old Hollywood studios. And another Golden Era has blossomed, thanks in part to television and the internet.

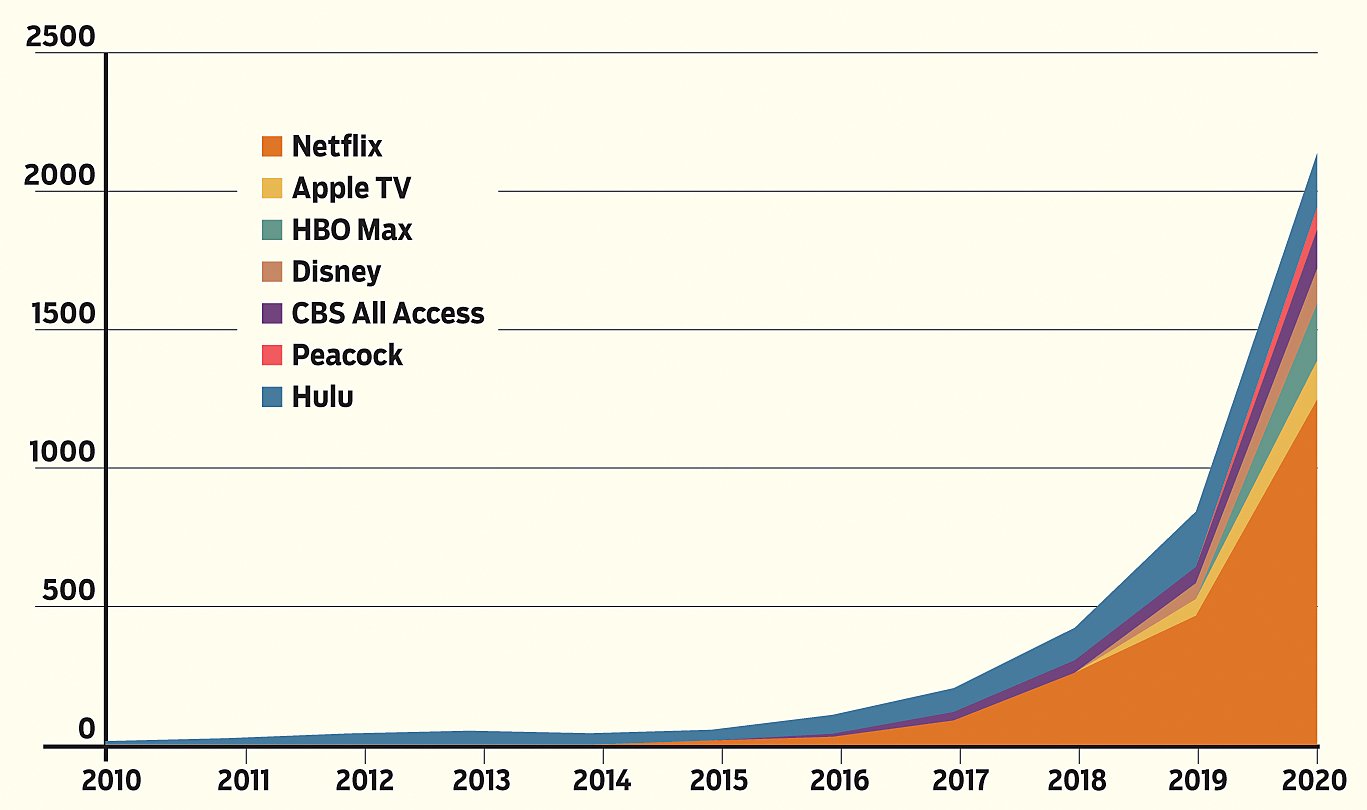

In 2009, after 60 years of television industry development, there were 210 scripted TV shows produced. A decade later, there were 532. And scripted shows were far outnumbered by unscripted programming. The unleashing of “over-the-top” (OTT) video streamed via broadband internet to home flat screens, tablets, and smartphones helped fuel this boom. In 2010, the total production of Netflix, Apple TV, HBO Max, Disney+, CBS All Access, Peacock, and Hulu, was 13 hours — for the year. In 2020, it was 2,136. (See Figure 1.) Netflix was the game changer: the company was streaming video to subscribers by 2007, but it jumped into the movie and TV studio business in 2013 — and all Hell broke loose.

Figure 1

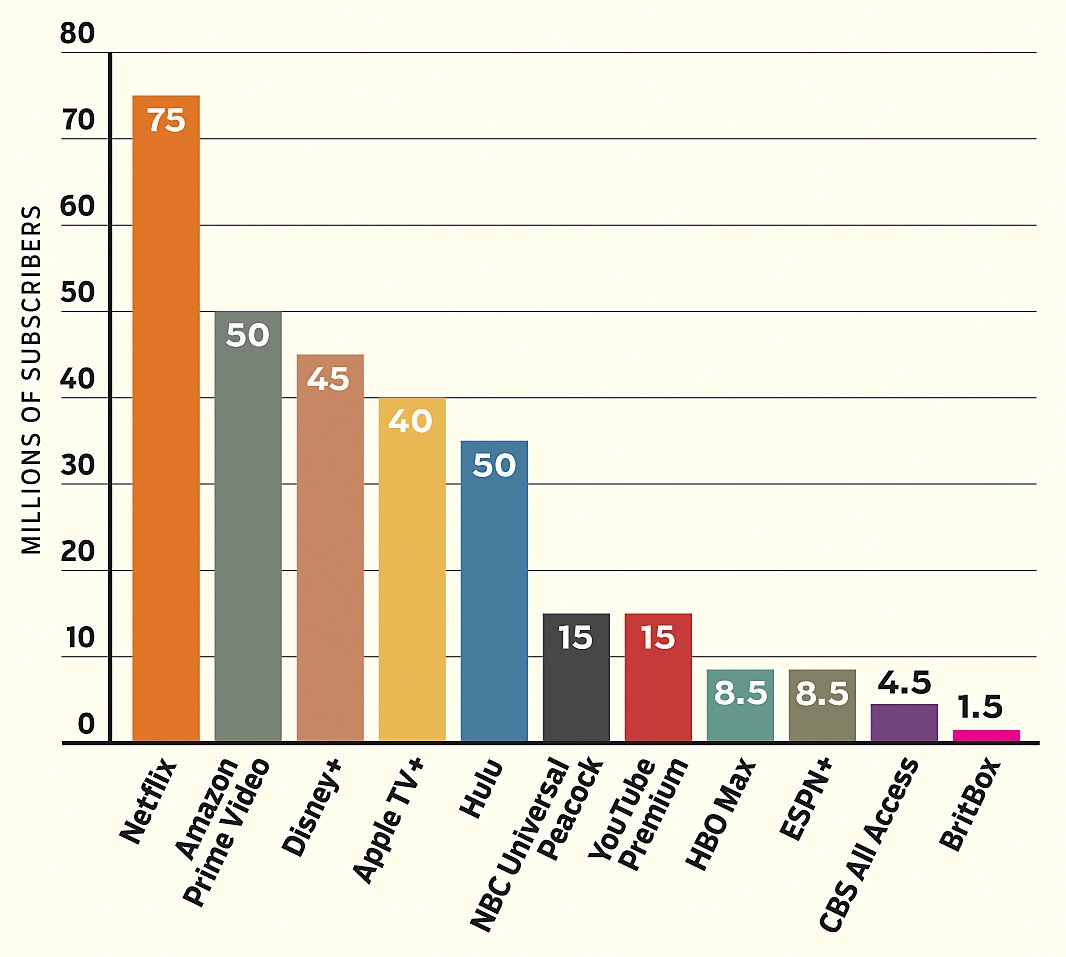

Figure 2

The radical reconfiguration of the marketplace — from "linear" program networks to video-on-demand — did not take place simply because of changes in technology. Three decades ago, cable TV operators were already giddy over the prospects of "pay-per-view" (PPV). But it was a flop. Yet now, the vision of a "500 Channel World" dreamt by cable billionaire John Malone in 1992 has come to pass, and then some, but not via Expanded Basic Cable or PPV. The Hollywood explosion runs video over cable TV operators' networks, but not within their menus. And vertical integration — decried, as with the Paramount ruling, for blocking competition — supplied the information superhighway for new products to emerge and then dominate.

As recently as 2005, a proposed merger between video rental chains Blockbuster and Hollywood Video was stopped by the Federal Trade Commission as monopolistic. As now seen, that market was irrelevant. What mattered was that cable operators and their telecommunications carrier rivals were building broadband access to the internet, adding massive capacity to supplant dial-up internet service — enough for real-time, internet-based PPV.

In 2011, Netflix's U.S. subscriber base was dominated four-to-one by traditional cable and satellite TV. This state of affairs was thought to be locked in. Harvard law professor Susan Crawford, in her 2013 book Captive Audience, noted that "the possibility of substituting online video for cable networks poses risks to both programmers and cable distributors." But the leading cable TV distributor, Comcast, which Crawford branded the "communications equivalent of Standard Oil," had the muscle to resist the threat. "The absence of any regulatory regime or oversight over the cable giant," she wrote, "makes it unlikely that Netflix will be able to challenge Comcast [which] has a number of options that will make it extremely difficult for independently provided, directly competitive professional online video to challenge its dominance."

Yet, by year-end 2021, Netflix customers will likely exceed those of the entire cable TV industry. The onslaught of virtual multichannel video program distributors (vMVPD) such as Apple, Google (YouTube), Sling (DISH), Roku, and Amazon has flushed out the major studios and TV networks, forcing them to chase the Netflix OTT model. HBO Max (AT&T/Time Warner), Disney+ (ABC/ESPN), Discovery+, Paramount+ (CBS–Viacom), and Peacock (Comcast–NBC–Universal) have jumped ship. (See Figure 2.) The entrants are dictating to the incumbents.

Surprise Ending

It is fascinating that Paramount's logic, while impressing regulators for seven decades, was so rudely upended. Today's explosion in video production has been triggered by the very forces alleged to be competitively problematic.

Cable was explicitly suppressed by the Federal Communications Commission in the 1960s. The agency argued that protecting broadcast TV from competition was in the "public interest" because an over-the-air oligopoly would supply news and informational programs supporting a healthy democracy. But it didn't. The discredited policy melted with the "deregulation wave" of the late 1970s and price deregulation in the 1984 Cable Act. Cable operators then won First Amendment rights in Preferred Communications v. City of Los Angeles (1986), unanimously decided by the Supreme Court.

With cable unbound, the ABC–CBS–NBC triopoly was finally laid low. By 1988, most U.S. households subscribed to cable. By the 1990s, cable was so profitable that it attracted competitive entry from satellite providers. DirecTV (launched in 1994) and DISH (1996) — feared by cable industry execs as the "Death Star" — forced cable providers to upgrade their 64-channel systems. The technological refresh enabled cable to match the crisper and more abundant digital channel bundles beamed from space. And it delivered a bonus: the cable companies could now offer the "triple play" of video, phone, and internet service.

This blindsided conventional wisdom. Bell Labs had years earlier developed high-speed data options for telephone carriers; our digital network future was planned and ready. But the rate-regulated phone companies had muted incentives for innovation and were sluggish in their deployments. Technological leadership shifted. Cable operators beat the phone carriers to residential broadband, pioneering a global internet disruption. It featured another clash of cultures, reprising the movie industry's classic battle of staid incumbents challenged by daring outsiders. "Bell executives sleep in pajamas with little feet in them," industry wags observed in the 1990s. "Cable cowboys sleep in the nude."

The March of Science plays a leading role in all of this. But so, too, the controversial practice of vertical integration. Combining video production and exhibition has been instrumental in creating today's streaming platforms, as well as the "studios" that crowd them with content. Show-producing competitors — Netflix, Google/You Tube, Amazon, Apple — have leveraged efficiencies in adjacent markets. These interlopers have forced the next wave of OTT rivalry by drawing the established content incumbents — Warner Bros., Disney, NBC–Universal, Discovery, Paramount — to join the competitive streaming fray. And, despite the predictions of the Supreme Court in Paramount, this has happened without stifling the upstarts. The recent $900 million sale of Reese Witherspoon's Hello Sunshine entertainment studio, producer of the popular streaming series The Morning Show and Big Little Lies, underscores that point.

Beyond Paramount

The lessons of Paramount seem poorly understood. The U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Antitrust issued a 2020 majority staff report (now the basis for at least half a dozen bills in Congress) urging a move to re-embrace 1940s regulation and celebrating Paramount:

The Subcommittee recommends that Congress explore presumptions involving vertical mergers, such as a presumption that vertical mergers are anticompetitive when either of the merging parties is a dominant firm operating in a concentrated market, or presumptions relating to input foreclosure and customer foreclosure.

But nowhere did the lengthy report consider the 1948 Paramount decision's actual performance, nor the role that vertical integration has played as a key enabler in the rise of today's Golden — or Platinum — Age for movies and television. It is revealing that the lure of progress pushed the world to ignore the Paramount constraints to create an online video world anew. That complaints are made about the scope and reach of tech platforms today, and the "fixes" of Paramount are offered as salvation, is a revealing pattern recognition glitch, too.

"As internet movie streaming services proliferate," wrote Analisa Torres, the federal district court judge who approved the Justice Department's relaxation of the Paramount rules, "film distributors have become less reliant on theatrical distribution." She noted that the largest studio was Disney, which did not own theaters; that one of the original Big Five, RKO, was basically out of business; and that another, MGM, released just three feature films in total in 2018 (as compared to Disney's industry-leading 10). And Judge Torres noted a more profound fact: "None of the internet streaming companies — Netflix, Amazon, Apple, and others — that produce and distribute movies are subject to the" Paramount rules limiting vertical integration.

The market for films has been turned upside-down. Content is orders of magnitude more diverse and competitive than it was under the old system. In the 1940s, consumer choice in video was defined by attending or not attending the Saturday double feature at the local theater. In the 1970s, it was selecting one of three primetime TV shows offered, per slot, by the broadcast networks. In the 1990s, we clicked across the Basic Cable TV menu — mocked by Bruce Springsteen's "57 Channels (and Nothin' On)." Now, broadband internet has emerged, pouring forth content produced by vertically integrated competitors. That might well make Zukor or Laemmle smile and even make Springsteen grin: 37 million channels on TV and much too much to watch.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.