Rapidly rising rents in the Los Angeles and San Francisco metropolitan areas have once again produced calls for government rent control. This November, Californians voted on Proposition 10, which would have overturned a state law prohibiting local governments from imposing controls on units built after 1995. The measure was defeated, with 61% of voters giving a thumbs-down on the measure. However, rent-control advocates will almost certainly undertake other efforts in the near future, especially given that 39% of Californians favor rent controls, a sizable political base from which to launch another campaign.

Rent-control backers’ reasoning is straight-forward: “The rent is too damn high!” Renters are being priced out of economically dynamic big cities, driving them out to the suburbs, out of state, or onto the street. And rising rents and proposed controls seem to be destiny in the Golden State.

The backers’ working presumption is that rent control (or its less onerous variant, “rent stabilization”) will benefit a substantial majority of (if not almost all) renters, especially low-income tenants. Conventional economic analysis tends to support this view, at least in the short run: though the controls may discourage the addition of new units, they will benefit current renters by giving them a break on their monthly payments. But this view is too circumscribed and doesn’t recognize that even renters who keep their apartments and houses in the near term and long term will be made worse off by the controls, even with lower rental payments.

Conventional Rent-control Economics

To understand this, we must understand the economics behind landlords’ search for the best combination of rent and unit “amenities” (e.g., carpet, painting, maintenance, cabinets, lights) and “features” (e.g., air conditioning, security systems, balconies, showers, window treatments, upscale appliances) that augment the value and costs of the units they offer for rent. The negative consequences for renters emerge because controls on rents force landlords to reconfigure their units’ combinations, taking away these amenities and features or reducing their quality even though the takeaways are worth more to the tenants than the money saved by rent controls. Even in the short run, landlords can reduce the amount of living space available for, say, tenant storage, limit the number tenants in each unit, and convert units into condos. In the longer run they can let rental units deteriorate at an accelerated rate, reducing the count of rent-controlled units.

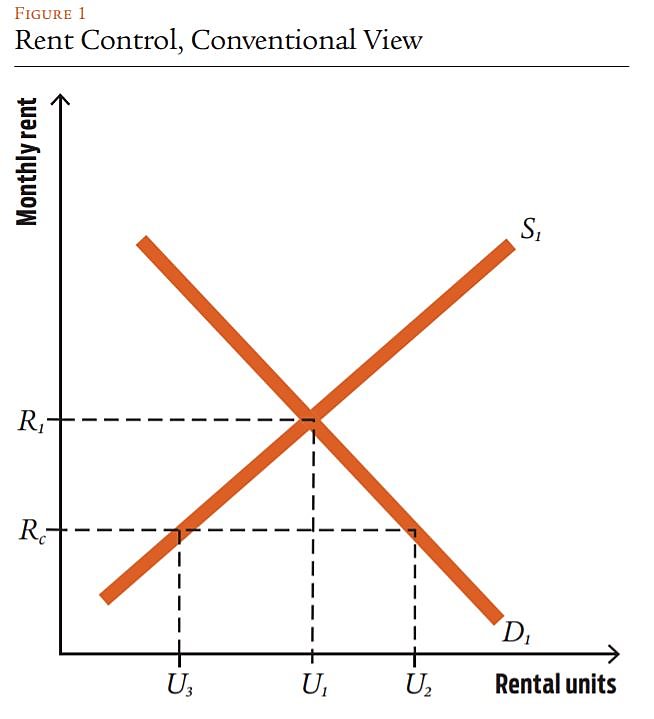

Figure 1 captures the supply and demand for basic rental units, which amount to a given square footage with minimal amenities and no features. This is an intentionally simple starting point to draw out the logic of adding features and, concomitantly, determining unit rents.

As in conventional rent-control analytics, the market forces in Figure 1 will lead to a monthly rent payment of R1 with U1 units made available—absent rent controls. Under conventional rent-control analytics, a controlled rent, Rc, will be set below R1. (There is no market effect from a rent control at or above R1.)

This figure illustrates how rent control alters the market equilibrium of rental housing in troubling ways:

- The controlled rent leads to a greater number of rental units demanded, U2, than would be demanded if the market rent were allowed to stay at R1.

- The supply of units will shrink from U1 to U3 as landlords take their units off the market, convert them to condos, fail to maintain them, and shelve plans to build more rental units.

- As a result, a shortage of rental units will grow over time, ultimately equaling the difference between U3 and U2.

Given the shortage, landlords can be choosier in selecting tenants. This means they will be more inclined to discriminate on whatever basis they like, including veiled discrimination for age, race, gender, or sexual orientation. Landlords can use a host of other characteristics to choose tenants, including physical attractiveness, whether the applicant has children or pets (and how many), criminal history, and credit scores. In short, rent control will boost various non-price forms of discrimination and will likely lead to an upgrade in the average “quality” of tenants from the landlords’ perspectives.

Rental Unit Features and Rent Control

Rental units typically come with an array of features. Even the most basic units have toilets, sinks, stoves, and carpet. In adding features beyond basic amenities, landlords follow a fundamental economic rule: add features (and/or upgrade their quality) so long as their prospective value to tenants is greater than the costs landlords incur in adding them.

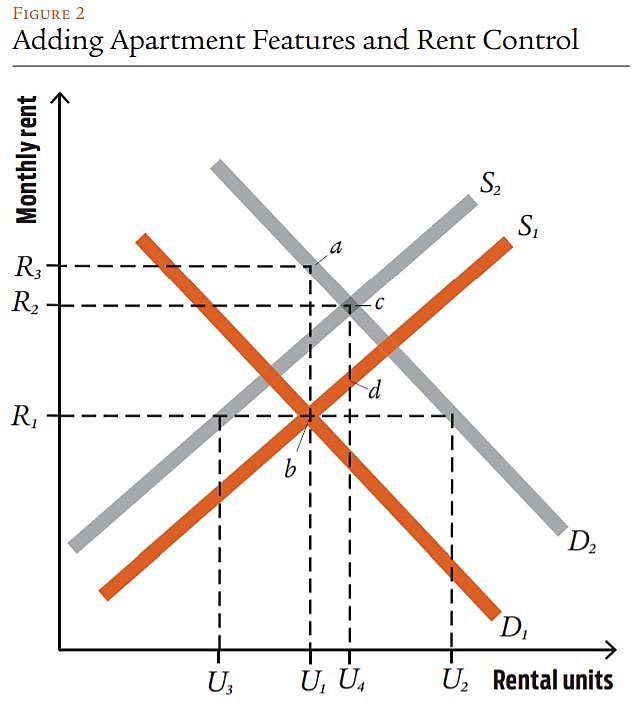

Consider the addition of air conditioning to basic units. If tenants value the air conditioning more than it costs the landlord to provide, the landlord has incentive to offer that feature. The demand and supply curves will shift, as represented in Figure 2. Because an air-conditioned unit is more desirable, the demand curve will shift outward from D1 to D2, moving upward the vertical distance ab, which represents how much more in monthly rent tenants are willing to pay for a basic unit with air conditioning. Likewise, the air conditioning will add to the landlord’s costs, which means the supply curve will shift upward from S1 to S2, moving the vertical distance cd. That distance reflects the increase in monthly rent the landlord must charge to recover the cost of the air conditioning.

Notice that the outward shift in the demand curve, ab, is greater than the upward shift in the supply curve, cd. This difference reflects the fact that the landlord will not add air conditioning unless it pays to do so, which is to say that ab must be greater than cd. If prospective tenants were only willing to pay $100 a month more for a rental unit with air conditioning but the air conditioning cost the landlord $150 a month, the landlord wouldn’t offer air conditioning (not for long, at least). If, however, the tenants were willing to pay $150 a month more for air conditioning that costs the landlord $100 a month to provide, the landlord would be leaving money on the table by offering only basic units. And even if a myopic landlord failed to exploit this opportunity, some enterprising real estate investor would recognize it, buy the landlord’s units, add the air conditioning, and raise the rent, pocketing the additional $50 (or somewhat less) per unit per month as added profit.

This new landlord would also be doing the tenants a favor in two ways. First, the number of units would rise from U1 to U4. Second, the tenants would receive ab in added value on their units but would have to pay less than that in additional rent, R2 – R1. The landlord would follow the same calculations in adding other features—maybe a higher grade of carpet, larger refrigerators, security systems—and would only stop adding features when the added cost exceeds the added benefits to tenants.

The general point is that financial forces and market competition will ensure that amenities and features mutually beneficial to landlords and tenants will spread across rental developments in markets. Landlords who, for whatever reason, refuse to add mutually beneficial features will tend to be pushed out of the market. By the same token, one of the reasons many people are priced out of rental markets is that other tenants are willing to pay more for added features. Rent controls are promoted as a means of controlling landlords, but they also control prospective tenants’ demands for amenities and features.

Rent-control Analytics Revised

We can now reconsider the economic consequences of rent control with the help of Figure 2. Let’s start with the market for rental units with air conditioning, settled with a market-clearing rental payment of R2 and with U4 rented units.

Let’s suppose that the local government designates R2 an “exploitive” or “immoral” rate for low-income tenants and decides that a reasonable, fair rent is R1 (the monthly payment for basic units). What’s a landlord to do? Conventional economic analytics assume that landlords either can’t do anything other than charge R1, as required, and marginally reduce the count of units. Supposedly the landlords could not see any way to take advantage of the resulting shortage of rental units (U2 – U3) and improve their units’ profitability (or reduce their losses). Rent-control advocates believe that by controlling rent they can magically suppress market competition and actually improve the economic positions of renters.

But in fact, landlords can and do react to rent control because of the shortage in housing units that would emerge. They have more tenants seeking their units than units available. Bluntly put, they don’t have to passively take what the local government says they must.

Landlords of basic units can engage in discrimination, as described above. For units above basic, they have other options: cut out the air conditioning, or reduce regular maintenance, or take away security guards, or do whatever else results in the greatest cost savings. In Figure 2, the removal of air conditioning will cause the tenants’ market demand to drop from D2 to D1, denying tenants the air-conditioning benefits equal to the vertical distance ab. As can be seen in Figure 2, that cut is more than the drop in the rental price, R2 – R1. The tenants who keep their units are worse off even though they are paying a lower, controlled rent.

Put differently, rent-control backers argue that rents are lowered by their control proposal. That is true for the out-of-pocket monthly rent payment, but it isn’t true of the tenants’ effective rent, which is the sum of the rent they pay and the lost value of amenities and features forgone because of rent control. In Figure 2, effective rent is represented by the controlled rental payment, R1, plus the loss in the air conditioning benefits, ab, which together equal R3. Notice that R3 is higher than the uncontrolled market rental rate, R2. That is, rent control increases, rather than decreases (as backers claim), tenants’ effective rents.

At the same time, landlords receive a lower effective rent. Their monthly costs go down by cd, but that cost reduction is less than the decrease in the rent they can charge, R2 – R1. As with the tenants, the landlords are worse off, on balance, because of the controls.

Notice in Figure 1 that the decrease in the available basic rental units is U1 – U3. The decrease in available rental units in Figure 2 is much lower, U4 – U1, than would have been the case had landlords not been able to take away features (resulting in a decrease in units to U4 – U3). This is the case because the landlords remove features and thus lower their costs, enabling them to continue to offer more—but less valuable—units to tenants.

In this way, price controls do damage in the covered markets. However, landlords, by taking away features, somewhat moderate the damage done: tenants are better off by losing features than losing more units. And it should be noted that landlords’ ability to take away features reduces their ability and willingness to discriminate against prospective tenants on whatever basis they fancy (e.g., race, gender, religion, physical attractiveness, pets).

Moreover, landlords must adjust their features, given extant competitive market forces that are at work establishing rental units’ combinations of amenities, features, and rent. Those landlords who are reluctant to remove the air conditioning, or curb regular maintenance, or delay the replacement of worn carpet can be expected to be bought out by landlords who are not so reluctant.

Again, landlords must heed competitive market forces. Rent-control backers seem to think that landlords, whom they chastise for being profit maximizing, will convert their businesses to charities and do the bidding of the rent-control advocates, even when rent-control advocates denigrate the landlords as “capitalist pigs” or other choice slurs. They scold landlords for having “monopoly power,” not realizing that the landlords’ market power will be enhanced by the shortages that rent control generates.

But there is more. Landlords, in addition to removing features, can develop an array of “tie-in sales.” For example, under rent controls in New York City decades ago, landlords began charging extra for keys to enter apartment buildings’ front doors. These charges, dubbed “key money,” capitalized the difference between the market rental payment and the controlled rent. The price of the key could be expected to vary with the controlled rent level (the lower the controlled rent, the more key money demanded) and the features removed (the more features eliminated, the less key money demanded). Key money is now illegal, but the effect of that control extension has been to increase the shortage of rental units.

Landlords can get even more creative. They can start charging for repainting, use of the pool, and use of provided furniture, as well as providing air conditioning, security systems, and other features. The one silver lining for tenants from these “creative reactions” to rent control is that they can result in landlords taking fewer housing units off the market than would otherwise occur.

Chasing the Rent-control Rainbow

Rent-control advocates might respond that, if their rent ceilings result in feature reductions, government can enact additional controls that mandate certain apartment features. But there is a limit to how much control government can exercise over rentals—if government truly wants to help renters.

With required features specified, landlords can move to other margins of their apartment “bundles.” They can simply withhold other features or become even more creative in adding tie-in sales. (New York City’s rent regulations are now a legal morass of what landlords can’t do.) Rent controls can push many landlords into progressively withdrawing maintenance as the market rent gradually moves up and the controlled rent remains fixed (or “stabilized” with increases in the controlled rent lower than increases in the market rent).

Along the control track, landlords can treat tenants progressively worse by using inconsiderate and unkind, if not outright nasty, comments and actions. Being nice and respectful to customers can be costly, after all. The landlords’ (and their managers’) surliness would reduce the development’s profits absent rent controls, but with rent controls the effect can be limited to causing tenants to go elsewhere (say, into up-market units with more features that the renters don’t consider worth the higher rents) but be replaced by other renters in the tight housing market.

To the extent that government can extend its regulations over more features (and amenities), landlords can be expected to do what comes naturally in the conventional rent-controlled models: take units off the market (through deterioration, conversions to condos, and scrapping building plans). This means that added controls can lead to more discrimination on several fronts among prospective tenants. Tenants with relatively low incomes and low credit scores (or with dogs and children) can expect their rental options to shrink more than those renters with higher incomes and credit scores. As rent controls are extended, low-income tenants can be expected to crowd ever more densely into basic units, or worse.

Of course, rent control advocates may continue to chase their rainbows by prodding government to extend controls ever more broadly over what landlords can do. In essence, government would assume the role of de facto owner—without investing public capital but with the usurpation of developers’ capital, all the while claiming the intent is to help hapless tenants.

That would be a neat trick if it could last. But developers would soon catch on to government’s tricks and stop risking their own capital in the jurisdictions where rent controls prevail. Of course, that would exacerbate the shortage of rental units at decent prices—precisely what the advocates oppose.

At that point, governments would recognize that the only option for providing affordable housing would be to build basic housing, dubbed “public housing.” Of course, government has long offered public housing, with disappointing results reflected in poorly maintained projects plagued by crime, cyclical poverty, and despair. The end of the rent-control rainbow is not a pot of gold, but a pot of coal.

Perverse Effects of Rent Controls on Maintenance

Landlords’ most immediately attractive line of defense against imposed rent controls might be to allow maintenance to slide, for example, by refusing to repair or delaying repairs on plumbing and electrical networks in their rental developments and by reducing the frequency of grass mowing, trimming shrubbery, and removing litter. Such strategies gradually transform landlords into “slumlords.” Tenants might not like the deteriorating looks of their rental homes but, with the housing shortage that emerges from rent controls, their complaints would be whistles into the wind.

The local governments might respond (mistakenly) by passing an ordinance allowing tenants to withhold their rents in the absence of repairs. If so, recognizing an opportunity to better themselves, many tenants would respond by failing to treat their units with the expected care. They might also sabotage their units by loosening, say, plumbing connections that can lead to leaks requiring repairs. If their landlords repair the problems intentionally created, the burden of the repair is on the landlords, who cannot pass along the repair costs to tenants in the form of higher rents. If the repairs are not made, then the tenants can withhold their rent payments, all very legally. The tenants might lose value in the maintenance problems they create, but they still can be expected to create the problems so long as the lost value from the repair problems is less than the rent payments they are able to miss.

Government would assume the role of de facto owner—without investing public capital, but with the usurpation of developers’ capital, all the while claiming that the intent is to help hapless tenants.

Through deterioration and withdrawal of units from the covered rental market, rent controls—if pursued vigorously over time by governments—can have effects similar to carpet bombing, with neighborhoods practically destroyed. Economist Thomas Sowell, in his book Basic Economics: A Common Sense Guide to the Economy (5th ed., Basic Books, 2014) observed years ago that New York City’s rent controls have had precisely that effect:

Owners have simply disappeared in order to escape the legal consequences of their abandonment, and such buildings often end up vacant and boarded up, though still physically sound enough to house people if they continued to be maintained and repaired. The number of abandoned building taken over by the New York City government over the years runs in the thousands. It has been estimated that there are a least four times as many abandoned housing units in New York City as there are homeless people living on the streets there.

Such are the perverse and unanticipated consequences of rent controls.

How Rent Control Favors the Rich

Advocates of rent control are concerned for the welfare of the poor and the “near poor.” As such, they should be distressed that the likely (and realized) effect of rent control is to benefit higher-income classes at the expense of others.

When rent control only applies to housing for the poor or to rental units that carry rents under some specified monthly rent level (now $2,700 in New York City), the rich benefit. The poor get fewer units in their housing markets because landlords will reduce the stock of rent-controlled units by leaving no-longer-profitable rental units vacant, converting their units to condos, or moving their investments to non-controlled units with high rents (and to other industries). Concerning the latter two strategies, as developers move to build uncontrolled high-price condos and rental units with luxury features, the supply of housing units for the rich increases. That, in turn, drives down high-end units’ prices and rents as compared to what they would be otherwise, absent rent controls on housing for lower-income groups. That is, the prices and rents of housing for the rich might still rise but by less than they would otherwise.

Despite the lower per-unit prices of these units as a result of stronger competition, high-end residential development further flourishes under these conditions, partially because the demand for those units can be expected to rise. This can be the case because, to obtain housing, some low- to moderate-income renters can be forced to move up-market, paying higher rents for more and higher-quality features that the renters consider not worth the added rents.

These supply and demand effects suggest that developers who specialize in converting low-income housing to high-income in wealthy markets (say, New York City) can find themselves building personal fortunes of millions and billions of dollars, helped along by rent control. Surely, many New York rent-control advocates would be chagrined to learn that their campaigns over the last 40 years have likely boosted, albeit marginally, the wealth of mega-developers like Donald Trump.

Conclusion

Conventional economics understates the consequences of rent controls. Its analytics suggest that, though controls can limit the supply of new rental housing, current tenants who keep their units are better off because of the controls. The perspective developed here is decidedly contrarian: even those tenants who stay in their units after the implementation of rent controls are worse off as measured by the difference between ab and R2 – R1, or by the difference between the rent they paid absent the control, R1, and the higher effective rent, R3, that they must pay because of the loss of features.

Rent-control advocates’ intentions are laudable: to make rental units more affordable to lower-income households. And they do accomplish this, but not in the benevolent way they think. Rent controls make the units more affordable by making them less desirable. As shown above, that lost value to tenants is greater than their reduction in rent.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.