- A large majority of health care spending involves a much smaller, less healthy portion of the insured population, which means that the distribution of health care spending is highly concentrated.

- Most individuals are healthy and need to spend very little on health care each year.

- Sustainable health insurance markets require that healthy customers pay more than they want so that less healthy customers can pay less for the care they need.

- Extensive government intervention, such as standardized benefits, generous subsidies, and limits on risk-based underwriting, is necessary in health care markets because those markets are prone to adverse selection and dangerous “death spirals.”

Voilà. These four points have given you the equivalent of graduate-level course work in health policy. You could pass yourself off as an expert. At a minimum, you could serve as either an insurance industry lobbyist, political advocate of conventional wisdom, or defender of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) intertwined mix of mandates, minimum benefits, insurance rating rules, and taxpayer subsidies. (Sometimes, it’s hard to keep those roles apart.)

But what’s more interesting is how limited is the empirical base on which this chain of standard assumptions is built and linked.

It turns out that health care spending, at least in the under-age-65 private markets for health insurance, has become less, not more, concentrated in recent decades. After a significant decline in spending concentration about two decades ago, it has stabilized at that lower level. There is a significant decline in concentrated spending among individuals from one year to the next. That decline in the “persistence” of high spending continues in people’s later years, though at a less significant rate.

Nevertheless, the overall pattern remains that a majority of individuals below Medicare age, or people not redirected to other forms of public insurance coverage (primarily Medicaid) as a result of longer-term disabling and income-limiting health conditions, just don’t need to spend that much of their income on health care. Whether they still should be required to pay much more for their insurance under the ACA or some other government intervention is largely a matter of policymakers’ choice rather than economic necessity.

Questioning the soft foundation of longstanding assumptions about the nature and sustainability of private health insurance markets matters across a range of contemporary policy discussions and health reform options. They involve issues such as community rating, standardized minimum benefits, risk-protection subsidies, the individual insurance purchasing mandate, health savings accounts, and retirement savings incentives.

DO LOW SPENDERS HAVE A DUTY TO PAY MORE?

Marc Berk and Zhengyi Fang offered one recent update to the still-modest volume of mainstream empirical research on these issues. They highlighted what should already be obvious to casual consumers of conventional health policy wisdom.

Berk and Fang found that the ongoing level of health care expenditures incurred by the lower-spending half of the U.S. population, for noninstitutionalized services, ranged between 2.7% and 3.5% between 1977 and 2014. They analyzed the most likely traits of low spenders and found these people considered themselves to be in good or excellent health. Compared to those in the upper half of annual health spending, the low spenders were younger (twice as likely to be below age 18 and four times less likely to be over age 65). They also were four times as likely to lack insurance coverage. High spenders were somewhat more likely to have public insurance coverage. The latter were more than twice as likely to report difficulty with immediate access to care.

So, for the substantial portion of the population that remains essentially healthy, has few direct concerns about access to care, and does not cost very much money to treat, it’s tempting to ask why public policy doesn’t largely “leave them alone.” But Berk and Fang instead raise concerns that the low spenders are less likely to support some provisions of the Affordable Care Act—perhaps because it does not benefit them, or at least provides benefits to others without requiring the others to make sacrifices while these low spenders do. This is the basis for the concern that if insurance coverage of the low spenders declines, insurers’ ability to offer affordable coverage to high spenders will also decline.

The implicit political translation at play here is that low spenders are often seen primarily as “donors” to fund the more expensive costs of high spenders—not through more-transparent taxes and public expenditures, but rather through the cross-subsidies produced by rating restrictions and coverage mandates.

DECLINING CONCENTRATION OF HEALTH SPENDING

Annual statistical snapshots of health spending distribution at the individual level can obscure two important trends: First, this spending itself became less concentrated in recent decades. Second, its persistence over longer periods of time is diminishing.

As often happens in policy-oriented extrapolations from statistical time series, findings can be shaped by how one slices and dices the underlying data. The time period highlighted, the cohorts of the overall population identified, the data source, and the subset of health coverage programs examined can shape different stories.

For example, Samuel Zuvekis and Joel Cohen were the first analysts to pick up a new trend toward less concentrated health care spending among top spenders since 1996. They used some of the same Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data that Berk and Fang would later use in their paper described above. However, Zuvekis and Cohen explained how, from 1996 to 2003, rapid growth in prescription drug spending was linked to slower growth in spending for inpatient care and thereby largely accounted for recent reductions in health spending concentration.

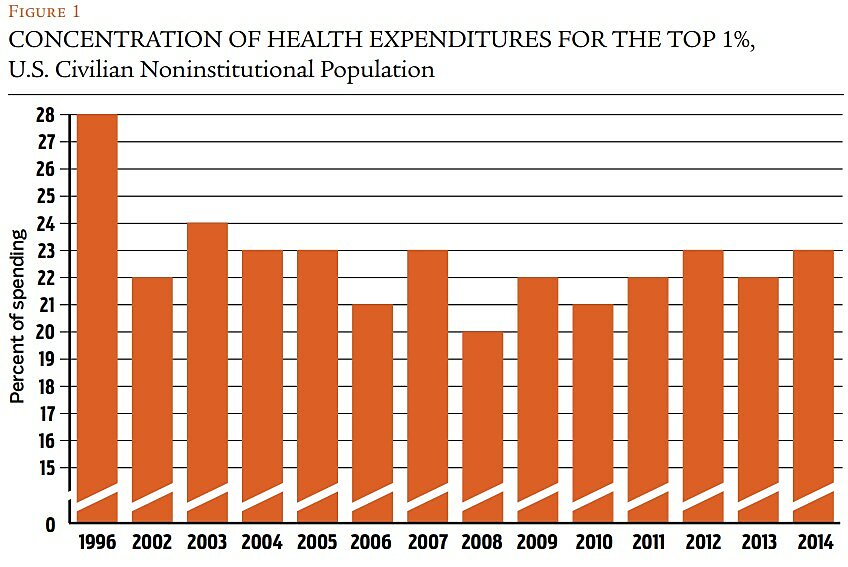

They began with earlier work by Berk and Alan Monheit that indicated that the top 1% of spenders in several surveys ranging from 1977 to 1996 accounted for more than one quarter of all health care expenses, and the top 5% accounted for more than half. Although the distribution of the top 5% apparently changed very little over those past three decades, subsequent examination found lessening of this concentration at the very top. William Yu and Trena Rice calculated that in 1998 the top 1% of spenders accounted for 28% of total expenditures, but that concentration measure decreased to 22% by 2002.

Zuvekis and Cohen concluded that increased use of prescription drugs was behind most of the reduced concentration in overall health spending. That conclusion resulted from their observation that recent spending on drugs was comparatively evenly concentrated across the population. However, they noted that the top 1% of people in the expenditure distribution still accounted for a relatively high share of all expenses, and that the top 10% accounted for nearly two-thirds. They call for efficiency-driven delivery system reforms to increase savings for this small but costly population.

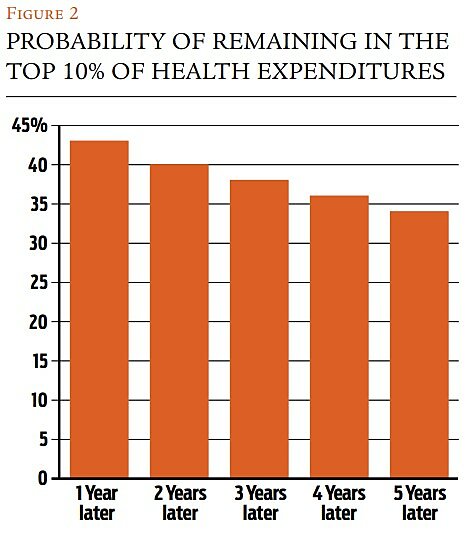

Top spenders / Steven Cohen enhanced this budding line of work by examining the “persistence” of concentrated levels of health spending in particular population cohorts over a two-year period. He noted the decrease in concentration at the upper tail (the top 1%) of the expenditure distribution from 1996 (28%) to 2013 (21.5%). Regarding persistence of this concentration among individual spending cohorts, Cohen found that of the top 1% in 2012, 14% maintained that ranking in 2013. Of the top 5% in 2012, 33.7% retained that ranking in 2013. Of the top 10%, 42.7% kept that top decile ranking in 2013, whereas 28% dropped down to the lower 75% level. So, as one expands the range of those in more concentrated spending cohorts, one finds more persistence across a two-year period. In the broadest cohorts, 74% of the individuals in the top half of the 2012 spending distribution retained that ranking the next year. At the other end of the spending distribution, roughly three out of four individuals (73%) in the bottom 50% of spending in 2012 similarly retained that ranking in the next year.

Low spenders are often seen primarily as “donors” to fund the more expensive costs of high spenders—not through more-transparent taxes and public expenditures, but through the cross-subsidies of mandates and restrictions.

Cohen’s analysis also unearthed some interesting findings about spending by the uninsured, who were disproportionately represented in the lower half of health care spending. The full-year uninsured comprised over 25% of those in the bottom half of health spending in both 2012 and 2013. Moreover, only 2% of individuals under age 65 who remained in the top decile of spending in both years were uninsured for all of 2013. In simpler terms, covering the full-year uninsured may not increase health care spending very much.

Other earlier analyses of spending persistence at the individual level through use of the MEPS data sharpened the direction of these trends. Steven Cohen and William Yu found that in 2005, 18.1% of the entire noninstitutionalized U.S. population in the top 1% of annual health spending retained that ranking in 2006. They also calculated that the full-year uninsured comprised 22.1% of the noninstitutionalized population under age 65 remaining in the bottom half of spending in both 2005 and 2006. Only 2.5% of those who remained in the top decile for both years were similarly uninsured during that period.

These MEPS-based analyses all remain limited to two-year intervals by that survey’s panel design for interviewing the same individuals over time. However, several other research efforts have tracked the spending distribution of smaller components of the U.S. population for somewhat longer periods.

Employer-sponsored insurance / Most notably, a research team led by Richard Hirth recently examined spending persistence within a large, under-65 population that was privately insured for six years through mainly self-insured medium and large employers. This unique study of long-term spending patterns relied on six recent years (2003–2008) of claims data from the Truven Health MarketScan Database. Over 2.5 million people could be followed for the entire period.

Hirth et al. found that almost 70% of individuals in the six-year sample never had annual health spending in the top 10% of the distribution. Of those in the top decile of spending in 2003, just 43.4% were likely to be there the next year (2004), but the drop-off in their spending then slowed in later years, with 34.4% of them in the top decile in 2008. In other words, the concentration of spending declines more moderately at the relatively high end (top 10%) over time, after the first two years. Another measure of this pattern can be found in how the top 1% of spenders in 2008 accounted for 24% of total health spending that year, whereas the top 1% of spenders for the full 2003–2008 period accounted for only 14% of all health spending during that interval.