In his new book Clashing over Commerce, Dartmouth College trade economist and economic historian Douglas Irwin “explores the economic and political factors that have shaped the battle over U.S. trade policy from the colonial period to the present.” The book divides American trade history into three periods: from the War of Independence to the Civil War; from the Civil War to the Great Depression; and from the Depression until today.

Founding to 1865 / Irwin presents the first broad period as characterized by a view of tariffs as a mere tool for raising government revenue. Until the creation of the income tax in 1913, tariffs provided the federal government with most of its money.

The founders, writes Irwin, “favored free and open commerce between nations and the abolition of all restraints and preferences that inhibited trade.” Like Adam Smith, they opposed the mercantilist—that is, protectionist—theories of the time. But that opposition was counterbalanced by some exceptions that Smith himself identified. One was concerns over national defense. Another was a desire for reciprocity—that is, equally open and nondiscriminatory trade with other countries—and possibly to retaliate through trade barriers in order to foster reciprocity (although Smith himself doubted that retaliation would work). After Independence, the British government discriminated against American exports. The adoption of the Constitution was due in part to the perceived necessity of negotiating trade reciprocity between the 13 states as a group and the British government.

A tension between free trade and protectionism appeared early in the Republic. In 1791, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton produced his Report on the Subject of Manufactures, which proposed tariffs and subsidies to foster domestic manufacturing given the “numerous and very injurious impediments” from Europe. As time went by, however, Hamilton’s Federalists became more free-trade, while the Republicans became more protectionist.

At the request of President Thomas Jefferson after clashes with the British Navy, Congress imposed a trade embargo against Britain in 1808–1809. Jefferson, who had written in 1787 that “a little rebellion now and then is a good thing,” adopted an uncompromising law-and-order attitude regarding the enforcement of the embargo. At the peak of the enforcement effort, American ships could not leave port, even for domestic destinations, without official clearance. “It is important,” he instructed his treasury secretary, “to crush every example of forcible opposition to the law.” Although Irwin does not put it this way, that was an early instance of Leviathan’s mission creep.

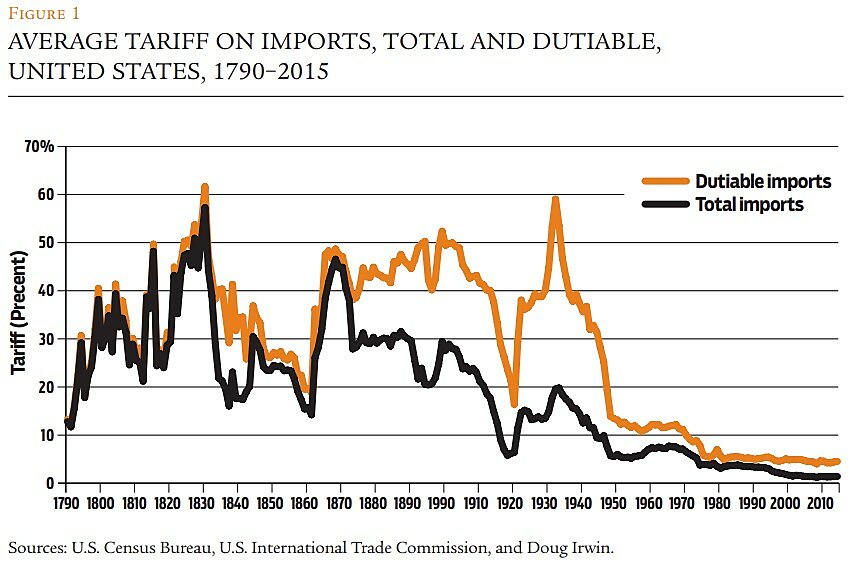

Figure 1 (p. 68) reproduces Irwin’s graph showing the evolution of the average tariff (or duty) on total imports (which include the free-entry list) and on dutiable imports. In both cases, the tariff increased from less than 15% in 1790 to about 60% in 1830, after the 1828 “Tariff of Abominations.” Tariffs were raised on raw materials (such as wool, hemp, and flax) and, to protect domestic producers of goods made from those materials, on similar imported consumer goods. Intervention begets intervention.

These tariffs sowed discord between the North, where manufacturers benefited, and the South, which consumed protected manufacturing goods while exporting cotton and tobacco. Tariff tensions led to threats of secession from South Carolina and the nullification crisis of the early 1830s.

The figure shows how tariffs were reduced from then on until the onset of the Civil War, “a quarter-century of gradually declining tariffs” under the Democrats. In 1859, the average tariff was less than 20%. Thus, according to Irwin, the idea that tariffs were a cause of the South’s secession is indefensible.

1865 to 1932 / The Civil War “brought about a major shift in U.S. trade policy,” launching a second broad period in American trade policy. The “temporary” tariffs imposed during the war “became the new status quo.” As shown in Figure 1, the period from the Civil War to the Great Depression was generally characterized by high tariffs on dutiable imports (about 40% to 50%). What pushed down the average tariff on total imports is that in 1873 Congress put coffee and tea on the duty-free list. The Underwood–Simmons tariff law of 1913, under the Democratic administration of Woodrow Wilson, dramatically reduced tariffs, but they were pushed back up in 1922 by a Republican Congress. As during the 19th century, the Republicans remained the party of protection.

Many economists (perhaps most of them) believe that tariffs did not contribute to the rapid industrialization of the United States in the 19th century. One prominent argument for this was made by Frank Taussig in his renowned Tariff History of the United States, which went through several editions between 1889 and 1931. Irwin argues that the large, diversified, and free internal market, with well-protected property rights, was sufficient to generate competition and growth. Moreover, open immigration compensated for the high post-bellum tariffs. Productivity showed especially fast growth rates in non-traded sectors such as services, including transportation, utilities, and communications. Add to this plentiful natural resources such as iron ore, copper, and petroleum, and we have more than enough explanations for the rapid development of America.

By the early 20th century, the United States was the world’s leading manufacturer and had been a net manufacturing exporter for a decade. By that time, America’s per-capita income quite certainly exceeded Britain’s by a substantial margin. “Between 1890 and 1913,” explains Irwin, “real wages increased roughly 30 percent because labor productivity increased by about 30 percent.”

The Democratic administration of Woodrow Wilson presided over tariff reductions during the 1910s. But even when they controlled the federal government, the Democrats were divided and, at best, lukewarm anti-protectionists. At any rate, they could not break the Republican old guard and the interests of the protected manufacturers it represented. The Republicans raised tariffs again in 1922. The infamous “antidumping” measures—a perfect excuse for protectionism that has survived until today—appeared in the 1922 tariff law. In the 1928 election (which made Republican Herbert Hoover president), the difference between the two parties shrank as the Democrats became more protectionist.

The debates of the 1920s illustrated a frequent conflict among industrial interests. Western ranchers wanted high duties on hides, while shoe manufacturers from Massachusetts did not. The chemical industry wanted an embargo on dye imports, while the textile industry did not. And so forth. Protectionism is always sectional and conflictual.

Perhaps the most infamous protectionist measure in U.S. history was the Smoot–Hawley tariff of 1930, which took half of its name from Rep. Reed Smoot of Utah. A committed protectionist, Smoot was after “internationalists who are willing to betray American interests and surrender the spirit of nationalism,” as he himself declared. The law increased the average tariff by about 6 percentage points, which the deflation of the Great Depression doubled (because specific tariffs translated into higher proportional tariffs as import prices decreased).

Economists broadly opposed Smoot–Hawley, with 1,028 of them signing a formal petition against it. According to Irwin, today’s consensus among economists is that the Smoot–Hawley tariff played only a small role in exacerbating the Great Depression, although it did provoke retaliation from many foreign countries.

1932 to today / In Irwin’s periodization, the third broad phase starts under the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. FDR was less suspicious of free trade than many of his precursors. He seemed to understand that solving the Great Depression required more international trade—even if, paradoxically, he tried to limit domestic free trade.

Irwin describes the period from 1932 until today as a quest for reciprocity—that is, the reduction of American trade barriers as a bargaining chip for other countries to do the same. In a sense, it was a return to the first period of American history.

One important pro-trade development early in this period was the adoption of the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) in 1934, which empowered the president to negotiate lower duties with the governments of other countries. The RTAA reduced the capacity of special interests to push their protectionist causes in Congress. Irwin also underlines the influence of a few pro-trade individuals such as Cordell Hull, a congressman from Tennessee who became Roosevelt’s secretary of state. Sen. Paul Douglas of Illinois later wrote of Hull, “Thus, the shrewd, hillbilly free trader and militia captain from the Tennessee mountains outwitted for beneficent ends the high-priced protectionist lawyers and lobbyists of Pittsburgh and Wall Street.” Everybody, however, seemed to go out of their way to emphasize that they were not proposing free trade.

The same protectionist fears were expressed then as today. In 1945, Republican Rep. Harold Knutson of Minnesota asked rhetorically, “Please tell me how you are going to provide jobs if you transfer our payrolls to Czechoslovakia, France, the United Kingdom, China, Germany, Russia, and India?” I wish we had more hillbilly free traders.

In 1941 Hull declared that, after the war, “extreme nationalism must not again be permitted to express itself in excessive trade restrictions,” and promoted negotiations toward that goal. John Maynard Keynes, who was a trade negotiator for the British government, thought that free trade would be replaced by economic planning and balked at what he saw as the State Department’s belief in “the virtues of laissez-faire in international trade.”

The international negotiations resulted in the adoption of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947 under President Harry Truman. American tariffs on dutiable imports were reduced by 21% on average. Combined with the increase in import prices caused by post-war inflation, this resulted in the average dutiable tariff declining from more than 30% in 1944 to 13% in 1950.

As shown in Figure 1, tariff reductions continued with new rounds of GATT negotiations. Writes Irwin, “The early postwar period brought about the most momentous shift in U.S. trade policy since the nation’s founding.” Many factors contributed, including a change in the Republicans’ protectionist absolutism, favorable public opinion even among trade unionists, and foreign policy concerns.

By the mid-1960s, however, more intense international competition—partly as a result of the container revolution that cut the cost of sea shipping—led to protectionist tensions resurfacing in America. In 1970, over a protectionist bill requested by President Richard Nixon and introduced by Democratic Rep. Wilbur Mills of Arkansas, Republicans and Democrats finished switching sides, the Democrats replacing the Republicans as the party of protection. Democratic Party constituents, including organized labor, felt more affected by import competition. The U.S. government imposed import restrictions to protect the apparel, shoe, and steel industries—often against GATT rules.

FDR seemed to understand that solving the Great Depression required more international trade—even as he tried to limit domestic free trade.

The Trade Act of 1974 made antidumping complaints by domestic companies easier. In 1976, by some calculations, the U.S. market was more protected by non-tariff barriers than the European Economic Community and Japan, although exports were less subsidized in America.

A severe double-dip U.S. recession from 1979 to 1982 combined with the significant appreciation of the dollar (from monetary policy) to squeeze domestic producers of traded goods, particularly in manufacturing. Despite his professed faith in “free trade”—which at least he dared call by its name!—Ronald Reagan and his administration made many compromises to protect producers of automobiles, steel, textiles, apparel, and some other goods, even invoking an “unfair surge in imports.” Japan was considered the big bad wolf of the times, much like China is today.

It was calculated that American consumers’ annual cost from textile and apparel protection amounted to more than $100,000 per job saved, several times the average wages in those jobs. A more active opposition from American purchasers of intermediate goods such as textile and steel helped contain the protectionist pressures.

The 1990s saw major initiatives to roll back trade barriers, including the conclusion of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the completion of the Uruguay Round of GATT, the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the welcoming of China into the world trade system. Despite his party’s protectionist drift, Democratic President Bill Clinton opposed protectionism and contributed much to the adoption of NAFTA. Public opinion also seemed to move away from protectionism but, as we would soon see, not irrevocably so.

In the 2000s, protectionist pressures rose up again with the so-called “China shock” after China joined the WTO. Partisanship and division started growing again, reaching their peak (thus far) with the election in 2016 of perhaps the most protectionist president in U.S. history. Figure 1 suggests that the reduction in tariffs has plateaued, but note that these data do not incorporate the increasing use of so-called “trade remedies” or special duties to compensate for alleged dumping and foreign subsidies.

Interpretations / It is possible, I suppose, for a reader to finish Clashing over Commerce with an optimistic outlook for American trade policy or, at least, with a mixed sentiment. After all, America has been much more protectionist in the past than recently.

But what is surprising, at least for an amateur student of American history, is the nearly continuous protectionist tendency of the U.S. government from the Founding to the present time and, when free trade was defended, the modesty and prudishness of its defenders. In the early 1830s, Sen. Henry Clay, inventor of the “American [protectionist] system,” stated that “to be free,” trade “should be fair, equal, and reciprocal.” So-called “fair trade” is not a recent invention. More often than not in the 19th century, the benefits of international trade were understood to attach exclusively to exports, like in the old mercantilist thought. There was not much understanding that tariffs are a tax on domestic consumers.

There were some happy exceptions. Treasury Secretary Robert Walker wrote in 1845:

That agriculture, commerce, and navigation are injured by foreign restrictions constitutes no reason why they would be subject to still severer treatment, by additional restrictions and countervailing tariffs, at home. … By countervailing restrictions, we injure our own fellow-citizens much more than the foreign nations at whom we propose to aim their force.

Another leader who understood, President Grover Cleveland, told Congress in 1887:

Our present tariff laws—the vicious, inequitable, and illogical source of unnecessary taxation—ought to be at once revised and amended. These laws, as their primary and plain effect, raise the price to consumers of all articles imported and subject to duty by precisely the sum paid for such duties.

Gerald Ford boasted on one occasion that he was “a proponent of free trade.”

At some point in the 19th century, political battles organized around partisan lines, even though both the Republican and Democratic parties were generally mildly interventionist, more or less protectionist, and rather devoid of philosophical foundations. The big difference is that the Republicans were protectionist because they defended the special interests of their electoral clienteles, such as manufacturers in the Northeast, and that the Democrats were less protectionist because they represented different electoral clienteles, such as the exporting South. A Republican congressman summarized the position of the two parties after the Civil War by saying that “the Democratic doctrine is a tariff for revenue with incidental protection, while the Republicans advocate a tariff protection with incidental revenue.”

All of this should remind us that free trade is free trade. The essence of protectionism is the state’s forbidding its own citizens or subjects to import what they want at conditions that they have individually determined to be the best available, and to forbid them to invest in foreign countries as they want, given the conditions they get there. Foreign interference should not be a reason for the government of a free country to submit its own citizens to more coercion. In a free country, free international trade should be a no-brainer, just like domestic trade.

Clashing over Commerce illustrates many elementary economic errors made by the protectionists. The Republicans’ 1908 presidential platform included the plank, “The true principle of protection is best maintained by the imposition of such duties as will equal the difference between the cost of production at home and abroad, together with a reasonable profit to American industries.” As Irwin notes, this idea of equalizing costs of production ignores the fact that differences in the (comparative) cost of production constitute “the very basis for international trade.” If two parties can produce the same things at the same costs, there is no benefit to be derived from exchange.

Clashing over Commerce illustrates the problem of collective action in trade policy. Producers’ benefits are concentrated, while consumers’ costs are diffuse. The cost of the textile and apparel protection for the average American household was $63 per year from the 1970s until the early 2000s. Consequently, while producers (capitalists and workers) lobbied the government, no consumer had a sufficient incentive to participate in lobbying and protests, even if the sum of the producers’ benefits was much lower than the total cost imposed to millions of consumers. Left unconstrained, the state develops into a coalition of producers, not an association of consumers.

International trade rules and institutions (like GATT and the WTO) can compensate for this bias. Another note of optimism is that trade integration leads importers of intermediate goods and large retailers to counterbalance the concentrated interests of import-competing industries. We see this phenomenon in the current debate on NAFTA, where many corporations side with consumers.

The worst in politics / When the demands of special interests are channeled through a welcoming political process, logrolling (that is, political horse trading) on a grand scale engulfs politicians. In 1909, Theodore Roosevelt chose to drop his push for tariff reform in exchange for Congress allowing him to expand the Interstate Commerce Commission. A more dramatic example: the so-called “dirty compromise” adopted by the 1787 Constitutional Convention saw the Southern delegates grant the federal government the right to regulate international commerce in exchange for continuation of the slave trade (plus a prohibition on export taxes). A common form of logrolling was for a congressman to trade his approval of some tariff pushed by another congressman in return for the latter voting for the former’s own preferred tariff.

During the 2005 congressional debates on the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), Rep. Robin Hayes of North Carolina’s 8th District announced, “I am flat-out, completely, horizontally opposed to CAFTA.” But Republican Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert persuaded Hayes to switch his vote by telling him: “In return for your vote, we will do whatever is necessary to help the people in the 8th District.” Gordon Tullock, the famous public-choice theorist, explained how this logrolling can produce policies that few people really want and impose a net cost for each citizen. (See Government Failure: A Primer in Public Choice, Cato Institute, 2002.)

David Wells, a protectionist nominated by Congress as special commissioner of the revenue in 1866, was shocked to discover how private interests operated in Congress. He admitted in private correspondence, “I have changed my ideas respecting tariffs and protection very much since coming to Washington.” There was nothing rational in the way that Congress treated protection demands; political greed was the motive.

Although Irwin may not go that far, Clashing over Commerce shows how protectionism brings out the worst in politics. For example, many congressmen secretly approved the accession of China to the WTO, but did not want to be seen voting for it if they knew it would otherwise pass. U.S. Trade Representative Charlene Barshefsky remarked that “the vast majority of members know this is absolutely the right thing for us to do,” but that “doesn’t necessarily mean … they will vote affirmatively.” When Congress discussed tariff bills in detail, members tried to include so-called “jokers,” that is, intentionally obscure formulations and convoluted definitions in order to sneak in the protectionist measures they wanted.

Protectionism dresses in the clothes of nationalism. James Swank, a driving force of the American Iron and Steel Association formed in 1864, wrote that “protection in this country is only another name for Patriotism,” and that “it means our country before any other country.” “I am an American, and therefore I am a protectionist,” proclaimed Samuel Randall, a Pennsylvania Democrat and House Speaker in the late 1870s. Donald Trump claimed that foreigners are “stealing our companies,” which is a nationalist fabrication.

In the 1880s, Rep. Samuel Cox of New York identified the thieves better. He understood that protectionism favors parts of the country at the expense of other parts. He declared (in a quote that by itself is worth the price of Irwin’s book):

Let us be to each other instruments of reciprocal rapine. Michigan steals on copper; Maine on lumber; Pennsylvania on iron; North Carolina on peanuts; Massachusetts on cotton goods; Connecticut on hair pins; New Jersey on spool thread; Louisiana on sugar, and so on. Why not let the gentleman from Maryland steal coal from them? True, but a comparative few get the benefit, and it comes out of the body of the people.

Protectionism leads to incoherent if not absurd results. In 1962, the European Economic Community doubled its tariff on imported poultry, leading to what was dubbed “the chicken war.” The U.S. government retaliated with higher duties on other goods, including a 25% tariff on light trucks. The chicken war has long subsided, but the truck tariff persists to this day. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was formed after the U.S. government imposed an import quota on oil in the late 1950s, and the same OPEC imposed an oil embargo on America in 1973!

Perhaps the best illustration of the consequences of compounding regulation is the sugar import quotas, which led farmers in Central America and the Caribbean “to stop producing sugar and start cultivating illegal narcotics that were smuggled into the United States, starting a war with drug traffickers,” Irwin explains. Or consider the U.S. government’s deficits in the 1970s and early 1980s, which pushed up the dollar (through foreign borrowing), stimulated imports, harmed American exporters, and fueled protectionist demands to the same government.

In the 19th century as today, economists who defended trade were attacked and ridiculed by populist politicians. Republicans rejected the theory of comparative advantage, described by one of them as “the refinement of reasoning to cheat common sense.” Sen. Henry Hatfield of West Virginia blasted academic economists: “Cloistered in colleges as they are, hidden behind a mass of statistics, these men have no opportunity to view the practical side of life in matters pertaining to our industrial welfare as a nation.”

Toward the future / I fear that the history of American trade policy does not augur well for the future of free trade. But I may be wrong, and I hope to be.

On one hand, it is true that the integration of supply chains has generated strong business interests against protectionism. Perhaps organized interests will end up aligned with what economists have known since David Hume and Adam Smith: free international trade is in the interest of consumers and the vast majority of individuals.

On the other hand, the ideal of free trade does not seem to have become more popular. Irwin himself rings an alarm: “What used to be called ‘trade agreements’ in the 1930s became ‘free-trade agreements’ in the 1980s and then were labeled ‘partnerships’ in the 2010s due to the negative connotation that ‘free trade’ now has in many quarters.”

And “free trade” has become less free as “partnerships” are now expected to include labor and environmental requirements and even provisions regarding such matters as gender issues. “Fair trade,” which is trade according to the latest political fads, is not free trade. Irwin notes a very important point: the recent orientation of trade agreements toward regulatory harmonization has politicized them and rendered them more likely to provoke political resistance. And the outlook for free trade has further deteriorated with the current mercantilist administration in the United States.

American trade history has witnessed no great debate on unilateral free trade, the idea that whatever other governments do, ours should allow us the freedom to import and invest as we want (“us” meaning each individual or group privately). It is not far from the truth to say that the closest to trade freedom that Americans ever got was the truncated alternative between reciprocity and protectionism. That most other countries have been no better is hardly a cause for optimism.

Whatever predictions one may draw from two and a half centuries of American trade history, and whatever the points on which one might disagree with Irwin, Clashing over Commerce is a very impressive book. Besides a detailed history of trade policy, it provides a general picture of American political and economic history. It is more impressive a book than Taussig’s was a century or so ago. Let’s hope that like Taussig, Irwin will update this book and publish new editions as time rolls on.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.