In the ongoing debate over patent reform, it is common to assert that there are “too many” patents, or that patents are “too strong,” or both. The result, so the argument goes, is that the patent system is being turned on its head. Rather than promoting innovation, the patent system slows innovation by entangling companies in a “thicket” of licensing negotiations and infringement litigation. But a minority school of thought has always expressed skepticism that thickets would ever persist. The reason is simple: markets don’t like to leave money on the table. When a patent thicket persists and the commercialization pathway is blocked, then money is being left on the table because a deal that could be made is not being made. That missed opportunity would seem to provide a powerful incentive to think constructively about how to unravel the thicket. If so, then markets would be expected to arrive at a solution, unlock the suppressed value, and divide it accordingly.

This debate reduces to a factual question: do markets really tolerate thickets for any significant period of time so that innovation is actually delayed or hindered to a significant extent? In recent published research, I have tackled this question. The results are remarkably consistent across more than a century of experience in a variety of U.S. markets and survive close scrutiny of contemporary information and communications technology (ICT) markets characterized by intensive levels of patent acquisition and litigation. Contrary to the thicket argument, markets are adept at identifying, preempting, and unraveling intellectual property (IP) webs that could have slowed down innovation and commercialization. Whether it’s radio, aircraft, and automobiles in the 1900s and 1910s, petroleum refining in the 1920s and 1930s, or ICT from the 1990s through the present, patent-intensive markets do not appear to suffer from the increased prices, reduced output, and delayed innovation that should appear if the thicket thesis were correct. This is true if the number of IP holders is small, which might be expected since the costs of reaching agreement are relatively low; but it is also often true when the number of IP holders is large, which is not expected.

I started by looking closely at the ICT market. This would seem to be an especially fertile environment for a patent thicket. Hundreds to thousands of patents can cover various components of a single device and those patents are typically dispersed among multiple holders. In theory, it is plausible that holders would fail to cooperate, a thicket would arise, and such products as the iPhone would never see the light of day. Yet big-picture trends in ICT markets all point away from that dark scenario. Simply compare the price and functionality of a laptop, tablet, or any other personal computing device today with the closest equivalent device 10 years ago. The comparison is remarkable: functionality continues to improve significantly while, adjusted for quality, prices decline significantly. Despite being “burdened” by heavy patenting activities, the electronics market shows every symptom of a healthy innovation ecosystem: lots of new features, declining prices, and expanding output.

All of this suggests that the right question to ask is not, how are patents delaying innovation, but rather, how are innovation markets doing so well even though patents are being acquired and enforced intensively?

ICT MARKET

ICT markets have figured out two solutions to patent thickets: standard-setting organizations (SSOs) and patent pools. The SSO structure is well-known: firms cooperate to agree upon a technology standard and then commit to license “essential” patents relating to the standard on “reasonable and non-discriminatory” (RAND) terms. The problem, as is also well known, is that the meaning of what constitutes “essential” and RAND is sometimes unclear.

A next step taken in some market segments is the pooling mechanism. The patent pool in its current form is typically organized by a third-party administrator, which then makes the licensed patents available to all interested licensees subject to a known royalty schedule and other terms. The pool has two virtues. First, it achieves economies of scale in licensing patents held by multiple holders to an even larger group of licensees. Second, it eliminates the pricing uncertainty inherent to the SSO structure. In doing so, the pool can promote adoption of the underlying technology standard as compared to a market that operates through a series of multiple “one-off” licensing transactions. Pools currently in operation cover fundamental standards that drive the digital economy, such as the “codec” standards used to store, transmit, and display audio, visual, and other data through set-top boxes, DVD players and discs, Blu-Ray players and discs, digital televisions, digital cameras, and MP3 players. The seemingly mundane licensing mechanisms administered by patent pools supply a good part of the legal infrastructure behind the revolutionary communications devices that are now a part of everyday life.

The pooling phenomenon exemplifies the basic principle that markets don’t like to leave money on the table. For believers in the thicket thesis, transactional blockages are just that: a dead end. For the market, however, those blockages are a profit opportunity that invites entry by transactional entrepreneurs, who innovate by offering an administrative solution that makes all interested parties better off.

BEYOND ICT

A patent skeptic might still contend that the modern ICT market could be a special case. True enough, although this possibility stands in some doubt because repeated survey studies of potential patent thicket effects in the biomedical space—the setting in which the thicket thesis was initially asserted—have found little supporting evidence. Alternatively, it might be asked whether the ICT market has something to say about markets’ ability to address IP thickets in general.

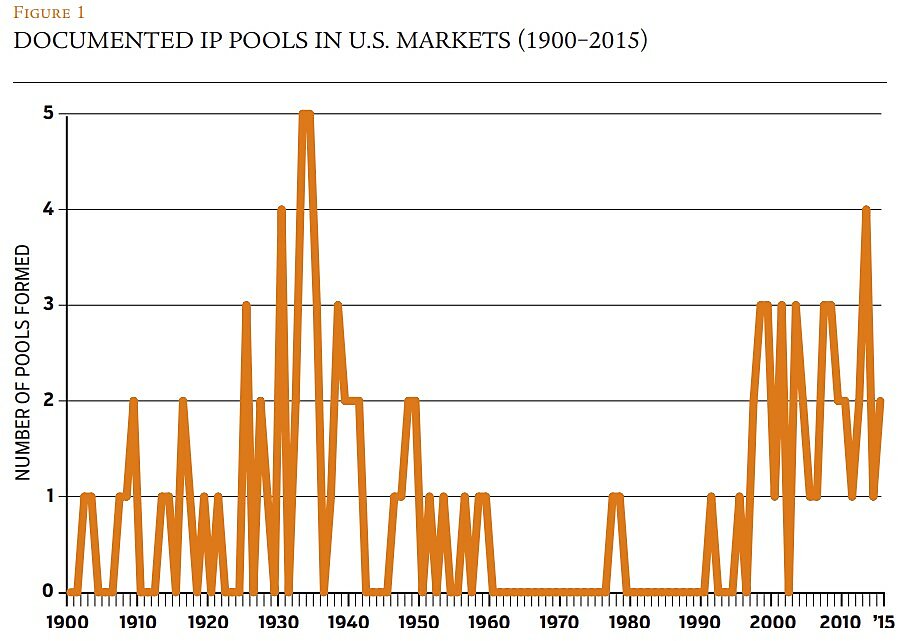

In an inquiry relevant to both perspectives, I studied over a century’s worth of market efforts to resolve IP thickets through pooling and similar arrangements in technology and content markets. Based on publicly available information, I documented a total of 106 IP pools and similar arrangements during 1900–2015, which is almost certainly an understatement because of data limitations in older periods. My findings are set forth in Figure 1.

Clearly markets regularly form pools to address, preempt, and unravel patent thickets by pooling IP rights and have been doing so for a long time. The pattern persists from the beginning of the 20th century, when pools were formed to resolve thickets in automobiles, aircraft, and petroleum refining (among others), to the present, when pools have been formed to facilitate the promotion of various electronics standards. Markets even outperform theoretical models by successfully forming pools in high transaction-cost environments in which IP rights are held by a large group of dispersed holders. Of the 106 documented pools formed since 1900, I found that 22 were formed by groups consisting of 10 or more licensors. (These are all modern pools formed by third-party administrators.)

As Figure 1 shows, however, pooling largely ceased during the postwar period (approximately the 1940s through the mid-1990s). The reason is governmental distortion: while never making an explicit prohibition, the antitrust agencies had increased liability for pooling to such high levels that no firm would rationally undertake such a venture. From 1933 to 1938, I found that 21 documented pools were formed, of which 90% were contested on antitrust grounds and all of which were dissolved or modified. The lesson is clear: markets are adept at forming pools so long as courts and agencies honor the contractual arrangements that underpin them.

MARKET SLOWDOWN?

It might be objected that, while markets are figuring out how to resolve a patent thicket through pooling, innovation slows down to some significant extent. We can never entirely resolve this question because it involves an unknown “what would have happened” counterfactual. But the available evidence on some key markets in which this claim is routinely made casts doubt on that possibility.

To illustrate, consider the famous litigation between 1903 and 1911 over the “Selden” patent, which claimed the internal combustion engine used in motor vehicles. The Federal Trade Commission, perhaps following the lead of academic commentary, has described the litigation as a case in which aggressive patent litigation—and the resulting legal uncertainty—blocked innovation and delayed growth in the early automotive industry.

However, there’s a problem: the facts do not support this contention. Historical market data show that Ford (the primary target of the holder of the Selden patent) and its shareholders thrived throughout the litigation, as did the motor vehicle market generally. From 1903, the year in which the holders of the Selden patent commenced an infringement litigation against Ford, through 1911, the year in which Ford prevailed in the litigation, Ford’s shareholders enjoyed an increase in revenues from $1.3 million to $42.5 million, an increase in profits from $283,000 to $13.5 million, and an increase in annual dividends from $88,000 to $5.2 million. At the same time, the U.S. auto market expanded even under the threat of patent litigation, as production of motor vehicles increased from 11,000 in 1903 to 210,000 in 1911. Most importantly, innovation did not cease during this time: in 1908, Ford introduced its key breakthrough, the Model T automobile. Again, the facts are clear: there is simply no slowdown in market expansion as the thicket thesis would anticipate.

PATENT POOLS

There is one disclaimer to all of the above. We might, and should, be concerned that patent pools and the associated royalty schedule could be used as a disguised mechanism for enforcing some type of collusive scheme. Horizontal licensing arrangements among patent holders, or a “hub and spoke” conspiracy coordinated through a series of vertical contracts with a single pool administrator, would provide the necessary infrastructure.

This is a legitimate concern and was the reason why antitrust law effectively prohibited pools from the 1940s through the mid-1990s and why the antitrust agencies took a close look at (but ultimately gave a green light to) early attempts to resuscitate the pool structure in the late 1990s. The concern was understandably salient (although not typically demonstrated) in the case of pools formed in the early 20th century, which were often closed arrangements confined to a small number of large incumbents.

A key component of the narrative that has supported “patent reform”—through both the America Invents Act of 2011 and Supreme Court decisions—turns out to be largely unsupported in multiple markets.

In hindsight, however, it is clear that the agencies grossly overstepped. Antitrust policy since at least 1995 has recognized the countervailing efficiencies of pooling and similar arrangements and, through agency actions, has signaled to the market its tolerance for pooling structures that incorporate structural precautions to mitigate collusion risk.

Based on my study of publicly available information on all currently operational patent pools in the ICT markets (in particular, the pools administered by the leading pool administrator, MPEG LA), these pools tend to conform closely to that implicit regulatory template and sometimes even exceed it. Three features are particularly comforting to an antitrust eye and stand in contrast to the early 20th-century pools. First, modern pools are typically administered by a third-party entity that has a repeat-player’s interest in setting “reasonable” fees for the licensee population, which must be persuaded to join other pools the administrator may establish in the future. This accounts for approximately 95% of all documented pools formed between 1995 and 2015. Second, modern pools are open vertical arrangements that make the pooled patents available to all interested parties willing to agree to the license terms. Third, at least in the case of the MPEG LA pools in the ICT market, the pools include a nondiscrimination clause according to which licensors are treated the same as licensees. That means that every cent that is added to the pool’s license royalty will also be paid by a licensor to the extent that (as is almost always the case) it at least licenses some patents from the pool for its manufacturing and other activities. If the licensor is a net licensee from the pool (that is, it pays in more royalties than it receives back out), then it should oppose any increase in the royalty. In short: there is limited likelihood that an open, vertical, and externally administered patent pool could be used to inflate prices and divide up profits among a pack of conspiring patent holders.

Conclusion

What can we learn from all of this? The most general lesson is that current reflexive skepticism among academics, policymakers, and significant business constituencies toward the value of the patent system may not always rest on solid ground. A key component of the narrative that has supported “patent reform”—through both the America Invents Act of 2011 and Supreme Court decisions—turns out to be largely unsupported in multiple markets extending over a century’s worth of historical experience.

To be sure, it may be the case that certain markets suffer from patent thickets for certain periods of time. But the fundamental question is whether those effects persist and matter, resulting in significant “macro” harms to innovation and commercialization. Plus, keep in mind that we haven’t discussed any of the gains that can be fairly attributed to the patent system—namely, increased innovation and improved ability to commercialize IP assets through financing, licensing, joint ventures, and other transactions.

Based on the evidence to date, there does not appear to be a credible reason to believe that markets actually suffer from commercially significant patent thicket effects for any sustained period of time, so long as courts honor pooling and similar arrangements that markets devise to avoid those effects. There may be other good reasons to be skeptical about certain features of our current patent system. However, the thicket thesis is not one of them.

Readings

- “A Financial History of the American Automobile Industry,” by Lawrence H. Seltzer. Houghton Mifflin, 1928 (reprinted by Augustus M. Kelley Publishers, 1973).

- “An Empirical Examination of Patent Hold-Up,” by Alexander Galetovic, Stephen Haber, and Ross Levine. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper #21090, April 2015.

- “Can Patents Deter Innovation? The Anticommons in Biomedical Research,” by Michael A. Heller and Rebecca S. Eisenberg. Science, Vol. 280 (1998).

- “Contracting into Liability Rules: Intellectual Property Rights and Collective Rights Organizations,” by Robert P. Merges. California Law Review, Vol. 84 (1996).

- “Effects of Research Tool Patents and Licensing on Biomedical Innovation,” by John P. Walsh, Ashish Arora, and Wesley M. Cohen. In Patents in the Knowledge-Based Economy, edited by Wesley M. Cohen and Stephen A. Merrill; National Academies Press, 2003.

- “Real Impediments to Academic Biomedical Research,” by Wesley M. Cohen and John P. Walsh. In Innovation Policy and the Economy, Vol. 8, edited by Adam B. Jaffe, Josh Lerner, and Scott Stern; MIT Press, 2008.

- To Promote Innovation: The Proper Balance of Competition and Patent Law and Policy, Vol. 3, published by the Federal Trade Commission, 2003.

- “View from the Bench: Patents and Material Transfers,” by John P. Walsh, Charlene Cho, and Wesley M. Cohen. Science, Vol. 308 (2005).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.