After a proposed new regulation finishes winding its way through the procedural morass that is required before it can take effect, it does not immediately have the force of law. The federal government has to formally publish a notice in the Federal Register announcing to the world that a new regulation is afoot.

This ultimate step does not entail any complicated procedure. In the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, when the regulatory state was moving with uncommon alacrity to ensure that copycat hijackings never occurred, regulations issued by a federal agency would get published within hours of being approved by the White House’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA).

However, that is far from customary. These days, regulations that have garnered the OIRA imprimatur can languish for weeks or even months before appearing in the Federal Register. For instance, in April 2014, Sen. James Inhofe (R‑Okla.) speculated that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency intentionally delayed the publication date of its greenhouse gas standards for new power plants in order to avoid a vote under the Congressional Review Act until after the fall elections. According to Senator Inhofe, the EPA intentionally held the proposal for 66 days.

There has been extensive research attempting to discern the magnitude and cause of the delays that federal agencies face as they navigate the regulatory process. Few dispute the notion that more expensive and controversial regulations invite greater scrutiny during the interagency review process, lengthening the time it takes for such regulations to get OIRA approval. However, less effort has gone into determining what affects the fate of rulemakings after the new rules leave OIRA. Is there something else besides sheer politics that causes an administration to delay the formal publication of a rule that has survived its regulatory process?

Strategic delay / In order to answer the question of why regulations face lengthy publication delays after OIRA review, we examined all major and “economically significant” final rules (those that have an economic effect of greater than $100 million annually) published between August 2004 and August 2014. That constitutes a total of 491 rules from 17 cabinet agencies.

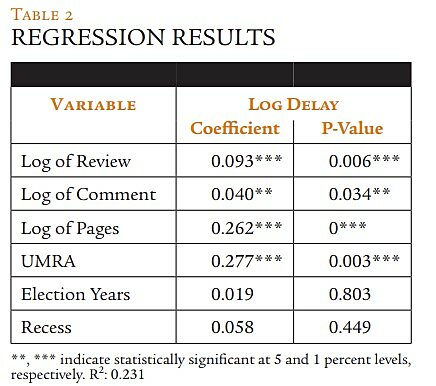

We compared this “publication delay” to several independent variables: the length of the OIRA review, the number of comments received, and status under the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (UMRA), which we used as a proxy to indicate whether the rule imposes significant compliance costs. We also included the number of pages the rule ultimately took up in the Federal Register when published, which we interpreted as a proxy for complexity, and whether the rule was published during a congressional recess or in an election year. As we previously pointed out in these pages, rulemaking tends to speed up markedly during presidential election years, regardless of the party in power (“No ‘Midnight’ after this Election,” Spring 2013).

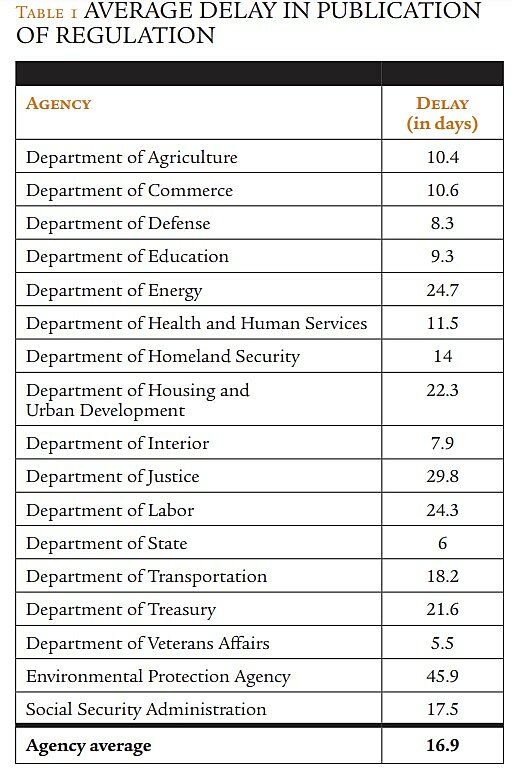

As shown in Table 1, the average delay between approval and publication in our sample was just under 17 days, but there was a high degree of variation between agencies. Not surprisingly, the EPA easily outpaced all other agencies, with an average publication delay of 45.9 days—more than double the overall average. Former OIRA official and current Rutgers University professor Stuart Shapiro opined that the delay is clearly strategic: “Because the EPA has the most controversial rules, it has the most need for strategic timing with the release of its rules.” On the other end of the spectrum, the Departments of State and Veterans Affairs made haste whenever OIRA approved their major rules, with publication delays of merely 6 and 5.5 days.

The best proxy we have to capture how controversial is a proposed regulation is the number of comments received on the rule. Table 2 shows the results of a regression we ran on the data. We found a positive and significant relationship between the number of comments received on a rule and the time it took for the final regulation to be published.

Another positive explanatory variable is the number of pages in the regulation. Intuitively, this might make sense, although we discount the EPA’s reason for this, which is that a rule’s length and complexity make the logistics of publishing the rule and getting a written version prepared and distributed somewhat time-consuming. Responding to questions about the EPA’s delayed regulations, EPA press secretary Liz Purcia stated that “EPA follows routine interagency and internal processes to ensure that formatting, consistency, and quality control issues are addressed before any rule package is published in the Federal Register.” Apparently, the VA has better editors than the EPA.

A more complete answer undoubtedly lies in the inherent nature of the EPA’s regulations, which tend to be controversial, impose significant compliance costs, and are generally lengthy and complicated rulemakings that necessitate spending a significant amount of time at OIRA. Those variables are not entirely independent: as review times increase, more comments flood into the agency, the page length escalates, and UMRA is triggered, the more likely the rule will have a publication delay greater than the overall agency average of 16.9 days.

In general, we find the model predicts a delay that is within five to seven days of the actual delay. For instance, a 2012 rule, “Joint Rulemaking to Establish 2017 and Later Model Year Light Duty Vehicle GHG Emissions and CAFE Standards,” spent 42 days at OIRA, received more than 370,000 comments, triggered UMRA, was 578 pages, and took place during an election and a congressional recess. The EPA delayed the rule’s publication by 48 days, compared to our model’s prediction of a 41-day publication delay.

For other rules, the regression yields even more accurate predictions of delay, coming within two to four days. For instance, in 2011 the Department of Energy published an efficiency standards rule for fluorescent lamp ballasts. Our model predicts that a rule with the same amount of review time (15 days), the same volume of comments (27), an equivalent number of pages (83), and that triggered UMRA like the efficiency rule did, should have a delay of 14 days. The ballast rule had an actual publication delay of 16 days.

Our findings also confirm what we noted in our Spring 2013 article, namely that publication delays virtually vanished during the so-called “midnight” period after Election Day and before the next president takes office. (The only such period in our sample was between Election Day 2008 and President Obama’s inauguration.) The average publication delay during that interregnum was just 12.5 days, or significantly below the agency average.

Curiously, election years and congressional recesses were not statistically significant factors in the model. Some of the inevitable regulatory delay that occurs in election years may occur elsewhere—agencies may delay submitting regulations to OIRA, for instance, or else drag out the negotiations with OIRA in getting a regulation through the system.

All administrations try to bury bad news as best they can. While any major regulation approved by Congress must ostensibly pass some cost-benefit standard, rules invariably necessitate some measure of compliance costs for the affected industries and a modicum of pain and frustration to boot. To lessen the blowback, administrations strive to release those rules at a propitious time so that the public’s attention is elsewhere. We suggest that the Obama administration has been especially keen on timing the formal release of new regulations for one political reason or another—which is certainly the prerogative of any White House and is far from unique.

Conclusion / Our model suggests that it is somewhat easy to anticipate what sorts of factors will serve to delay a rule’s eventual publication. That knowledge may be of little comfort to businesses that must spend money to comply with those rules and regulations. We suggest that the very publication of this analysis may serve to lessen the political games that administrations play with the timing of final regulations, by shedding a light on the factors that determine such delays.

Macroeconomist Robert Lucas suggested in the 1970s that no economic forecast can be consistently correct when it comes to forecasting interest rates. If the market perceived a forecaster’s model as being somewhat reliable and it predicted that interest rates would fall by 1 percentage point tomorrow, the market’s actions would conspire to make that happen more or less immediately.

Our model captures quite well the behavior of regulators when they need to publish a new regulation that has some modicum of controversy attached to it. Whether this model holds up over time or breaks down when the regulatory policy community—and the government—sees the quantification of what we suggest is baldly political activity remains to be seen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.