It is often argued that raising cigarette taxes will significantly reduce the consumption of cigarettes. Consider these two quotes from researchers at the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education (CTCRE) at the University of California, San Francisco, which is one of the leading anti-smoking organizations in the country:

There is a strong consensus that people smoke less as the price increases, with a price elasticity of –0.4 for adults and –0.65 for adolescents.—Stanton Glantz

An extensive literature has shown that in response to a 1 percent increase in cigarette prices, overall cigarette consumption among adults would fall by somewhere between 0.3 and 0.7 percent, with about half of the reduction being attributed to the reduced number of current smokers and half attributed to the reduced number of cigarettes consumed per smoker.

—Hai-Yen Sung, Wendy Max, and James Lightwood, comment to U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The hypothesis expressed in these quotes, that higher cigarette taxes save a substantial number of lives and reduce health care costs by reducing smoking, is central to the argument in support of regulatory control of cigarettes through higher cigarette taxes.

Of course, lawmakers have other incentives for raising cigarette taxes. States collected more than $17 billion in cigarette excise taxes in 2012, representing slightly over 2 percent of all revenues collected at the state level. Still, government revenue ostensibly is a secondary consideration to policymakers.

What if, however, higher cigarette taxes do not have much effect on cigarette consumption? Would the public still support tax increases, particularly when the resulting revenue comes predominantly from low-educated, low-income persons? That question is not simply theoretical because there are plausible reasons to believe that, in the current high-tax environment, additional cigarette tax increases will have relatively little effect on smoking. Consider who currently smokes: at roughly $6 per pack (with approximately $2.50 of that tax) and after large increases in cigarette taxes over the last decade or so, those who smoke have revealed that they have strong preferences for smoking. Accordingly, it is reasonable to expect that further tax increases may have little effect on cigarette consumption.

Additionally, there is increasing concern over the regressivity of cigarette taxes. Compared to national smoking rates of 20.5 percent for men and 15.8 percent for women, more than a third of men and nearly a quarter of women with earnings below the federal poverty level were current smokers in 2012. Not only are people in poverty more likely to smoke, but they also devote a much larger share of their income to cigarette purchases. From 2010 to 2011, smokers earning less than $30,000 per year spent 14.2 percent of their household income on cigarettes, compared to 4.3 percent for smokers earning between $30,000 and $59,999 and 2 percent for smokers earning more than $60,000.

In this article, we summarize a study we conducted that focuses on the effect of recent, large cigarette tax increases on the smoking behavior of adults ages 18–74. Estimates from our study suggest that the association between cigarette taxes and either smoking participation or number of cigarettes smoked is small, negative, and not usually statistically significant. In terms of a price elasticity of demand, our estimates imply an elasticity of –0.065, which is one-fifth to one-tenth the size of the widely cited estimates offered by the CTCRE. Our substantially lower estimates of the responsiveness of cigarette consumption to changes in taxes (or prices) alter the basic cost and benefit calculation of cigarette taxes. For example, our estimates suggest that a $1 increase in federal cigarette taxes, as proposed by President Obama in his last budget, would reduce smoking by less than 1 percent. In sum, our study suggests that future cigarette tax increases will have relatively few public health benefits, and the justification of future taxes should be based on the public finance aspects of cigarette taxes such as the regressiveness, volatility, and rate of revenue growth associated with those taxes.

CIGARETTE TAXES AND CONSUMPTION

An often-referenced graph of the relationship between cigarette taxes (or prices) and consumption is almost sufficient to demonstrate the motivation for our study and the veracity of our findings. Figure 1 shows the relationship between cigarette consumption and cigarette taxes over the time period 1980–2009. One can see that, from 1980 to 1994, there was a relatively strong negative relationship between cigarette taxes and consumption—as taxes (and prices) increased steadily, consumption decreased steadily. However, after 1994, the relationship largely breaks down. Cigarette consumption continues on the same steady downward path after 1994, but taxes remain flat between 1994 and 1998 and then spike between 1998 and 2009, with no noticeable change in the trend in cigarette consumption. In short, after 1994 there is little association between changes in cigarette taxes and changes in consumption. Years with big tax (and price) increases are not associated with larger than average changes in consumption, and consumption continues to decline even when taxes (prices) remain largely unchanged.

At a minimum, Figure 1 strongly suggests that the responsiveness of cigarette consumption to price has declined markedly in the recent period. Remarkably, this and similar figures are still used by advocates to argue for the public health benefits of cigarette taxes. For instance, according to the anti-smoking group Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, "Although there are many other factors involved, comparing the trends in cigarette prices and overall U.S. cigarette consumption from 1970 to 2007 shows that there is a strong correlation between increasing prices and decreasing consumption." That assertion may have been true prior to 1994, but over the last 20 years it is no longer supported by the data. Instead, the data in Figure 1 appear to be consistent with our findings—that, at most, in the recent past, there was a small negative association between cigarette taxes and smoking. We now summarize a more sophisticated assessment of this issue.

OUR APPROACH

To conduct our analysis, we focused on states with recent large cigarette tax increases. Specifically, we selected 19 states enacting 22 of the largest tax increases during the period covered by our data. The decision to focus on large tax increases is motivated by the simple argument that changes in consumption should be greatest for the largest tax increases. Focusing on large tax increases is also advantageous from an empirical standpoint because larger effects are easier to detect reliably than smaller effects.

For each state in our sample, we selected a group of comparison states that are matched on smoking rates and other demographic factors in the period prior to the state tax increase. States with statistically similar rates of smoking in the pre-tax period and that had no corresponding change in their cigarette tax were paired with the treatment state enacting the tax increase. As an example, Oklahoma's state cigarette excise tax was raised from $0.23 to $1.03 on January 1, 2005. Six states (Kentucky, Missouri, Indiana, Kansas, Tennessee, and West Virginia) had rates of smoking statistically similar to Oklahoma's in the pre-tax period; however, Kentucky also enacted a cigarette tax increase and therefore was excluded from the group of comparison states. This process was repeated for all 22 instances of tax increases we examined, resulting in an average of 11.7 states qualifying as comparison states for each "large tax increase" treatment state.

Using the sample of 22 treatment states that experienced large tax increases and their corresponding comparison group of states, we conducted a pre- and post-test comparison; we compared changes in smoking pre-to-post tax increase in the state that had raised taxes to the change in smoking over the same period in the comparison group of states that did not raise taxes. We combined these 22 "experiments" into one group to obtain the average (weighted) change in smoking caused by taxes in the 22 states.

To test the validity of our approach, we created a placebo experiment in which we chose the same treatment/control groupings, but in periods when there were no tax changes for either the treatment state or comparison states. We then randomly assigned a $0.50 tax increase to one of the states in the group and conducted our analysis as described above. Essentially, we created a series of "pseudo" tax increases using states and time periods where no actual tax changes occurred. If our approach was valid, then we expected estimates from the placebo experiment to be zero because no actual tax increase took place. In fact, the validity of our approach based on this placebo analysis was strongly confirmed.

The data for our analysis were drawn from 15 waves of the Current Population Survey Tobacco Use Supplement (CPS-TUS), which is a survey of tobacco use sponsored by the National Cancer Institute spanning the years 1995–2007. The CPS-TUS asks several questions regarding tobacco usage, including whether the respondent was an everyday or someday smoker. In addition, if the respondent is classified as an everyday smoker, the survey asks for the average number of cigarettes smoked each day. We defined smokers to be everyday smokers and consider someday smokers to be nonsmokers in order to maintain consistency in our estimates of smoking intensity.

We constructed two dependent variables. The first is a measure of smoking propensity and is a binary variable equal to 1 if the respondent is an everyday smoker and 0 otherwise. The second dependent variable is a measure of smoking intensity and is equal to the average number of cigarettes smoked daily. (This variable equals 0 if the respondent is a nonsmoker.)

The CPS-TUS also contains demographic information including age, sex, race, education, marital status, employment status, and family income, which are used in the analyses. We limit the sample to adults ages 18–74.

Estimates of the association between taxes and smoking were obtained using standard regression techniques. For the analysis of whether a person smokes or not, Logistic regression is used, and for the analysis of the daily number of cigarettes smoked, General Linear Model (Negative Binomial with log link) regression methods are used.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the results from our analysis. The top panel reports estimates of the effect of cigarette taxes on the probability that a person smokes or not. The bottom panel presents estimates of the effect of cigarette taxes on the daily number of cigarettes smoked.

Column 1 in the top panel lists the estimate of the association between cigarette taxes and smoking participation for adults ages 18–74. The estimate is negative, close to 0 and not statistically significant. The estimate from the Logistic regression is somewhat difficult to interpret, so it is easier to focus on the elasticity, which is listed in row 2. The elasticity measures the percentage change in smoking in response to a 1 percent change in the tax. The elasticity is –0.015, which is very small and not statistically significant. It implies that a 100 percent increase in the cigarette tax would decrease smoking among adults by 1.5 percent. In columns 2–4 of the top panel, we show estimates of the association between cigarette taxes and the probability of smoking for three age groups: 18–34, 35–54, and 55–74. Focusing on the elasticity estimates, none are statistically significant, and all are small in magnitude (less than +/– 0.05). Moreover, there is no evidence that the responsiveness of smoking to changes in taxes (prices) is more negative for younger adults. In fact, the estimate of the elasticity for adults ages 18–34 is positive (and not statistically significant). Even if we form confidence intervals around the estimates of the tax elasticities using the standard errors shown in parentheses below the estimates, the lower bound estimates (the largest negative numbers) formed by the confidence interval remain quite small. In sum, estimates in the top panel of Table 1 indicate that adults are quite insensitive to changes in cigarette taxes. Large changes in taxes—for example, 100 percent—would bring about trivial changes in smoking of 1 percent to 2 percent.

The bottom panel of Table 1 presents estimates of the effect of cigarette taxes on the number of cigarettes smoked per day. In this case, none of the estimates are statistically significant and all are small (half are positive). Thus, similar to estimates of the effect of taxes on the probability of smoking, estimates of the effect of taxes on the number of cigarettes smoked also indicate that adults’ smoking behavior is largely insensitive to changes in taxes.

Synthetic control approach / An alternative, although related, way of assessing the effect of cigarette taxes on smoking is to use a more sophisticated method, referred to as a synthetic control approach, to select comparison states for states that experienced large tax increases. In the analysis underlying Table 1, we selected states based on the level of smoking prior to the tax change. The synthetic control method selects comparison states on the trend in smoking prior to the tax change. Selecting comparison states on the basis of prior trends in smoking is advantageous because the research design compares changes in smoking trends pre-to-post a tax change and assumes that, in the absence of a change in taxes, trends in smoking would be the same in states that did and did not change taxes.

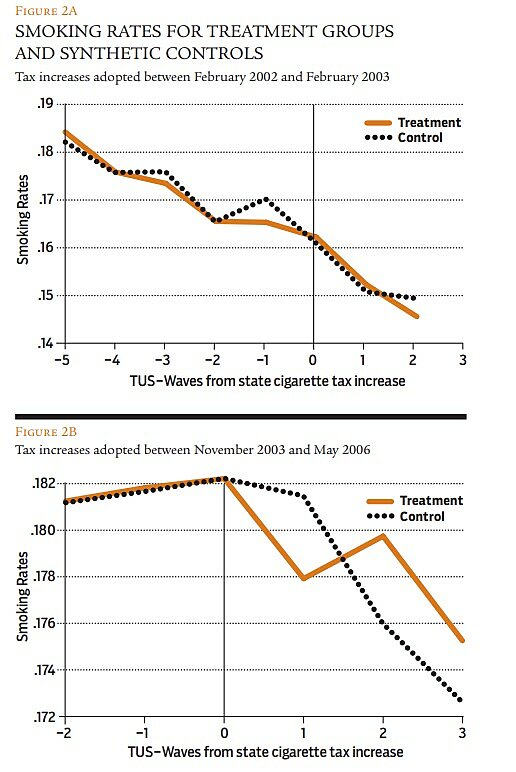

To conduct this analysis, we grouped treatment states together based on the timing of the tax change. One group of states increased taxes between February 2002 and February 2003 and the other group increased taxes between November 2003 and May 2006. For each group, we selected an appropriate group of comparison states using the synthetic control approach. The trends in smoking in the treatment and comparison states are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2A, which applies to states that increased taxes in 2002–2003, shows a consistently declining trend in smoking propensity in treated and control states and the groups appear to be relatively well matched in the period prior to the tax change. Post tax, smoking rates are slightly higher in the treated states than in the control group with the exception of the final period. Overall, the evidence in Figures 2A and 2B is consistent with evidence in Table 1 and indicates that cigarette tax increases are not strongly related to adult smoking behavior.

DISCUSSION

While the conventional wisdom is that cigarette taxes reduce adult smoking and in doing so serve an important public health function, the actual evidence to support this conclusion is relatively sparse. We revisited the issue of cigarette taxes and adult smoking and extended the literature in two ways. First, we focused on recent large tax changes, which provide the best opportunity to empirically observe a response in cigarette consumption. Second, we employed an underused but well suited methodology that is based on carefully selecting appropriate comparison states.

Overall, estimates indicate that the association between cigarette taxes and either smoking participation or the average number of daily cigarettes consumed is negative, small, and not usually statistically significant. Tax elasticities with respect to smoking participation and number of cigarettes smoked ranged from –0.05 to 0.04 and centered at –0.02. As noted in the introduction, if we convert the tax elasticity pertaining to smoking participation for adults into a price elasticity, we obtain a price elasticity of –0.065, which is one-fifth to one-tenth the size of estimates commonly used in policy discussions. The small elasticity undermines claims that cigarette taxes can still serve an important public health function by reducing smoking substantially. Those claims appear inconsistent with simple descriptive data (e.g., Figure 1) and more careful empirical analyses.

Our analysis of the association between cigarette taxes and adult cigarette use suggests that adult smoking is largely unaffected by taxes. At best, cigarette tax increases may have a small negative association with cigarette consumption, although it is difficult to distinguish the effect from zero. In practical terms, that implies it will take very large tax increases—perhaps on the order of 100 percent—to reduce smoking by at most 2–3 percent. This finding raises questions about claims that, at the current time, tax (price) increases on cigarettes will have a significant public health effect through reduced smoking. It may be that in a time when the median federal and state cigarette tax is approximately $2.50 per pack, further increases in cigarette taxes will have little effect because the pool of smokers is becoming increasingly concentrated with those who have strong preferences for smoking.

Consider the tax burden on low-income persons (e.g., annual earnings of $20,000–$25,000) of further cigarette tax increases. An increase in the federal cigarette tax of $1, as recently proposed, will increase the price of cigarettes by approximately 15 percent (assuming an average price of $6). If low-income smokers do not respond by cutting back on consumption, the increase in price caused by the tax will increase expenditures on cigarettes by approximately $480 per year for this group (assuming that the price of cigarettes consumed equals 14.2 percent of income, which is consistent with the academic literature). Even if they decrease smoking (i.e., everyone smokes a little less) by the amount implied by a price elasticity of –0.065, the increase in federal taxes will increase their expenditures on cigarettes by approximately $450 per year. The increased expenditure is greater than the $400 payroll tax rebate of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Moreover, this is a permanent increase in expenditures for low-income persons that will occur year after year.

Finally, what are some of the costs and benefits of a $1 federal tax increase in terms of health? In 2012, there were approximately 42 million smokers in the United States and the typical smoker consumed about one pack a day. That represents approximately 15.3 billion packs per year. An increase in the federal cigarette tax of $1 will raise prices by $1 (assuming the full cost of the tax is passed on to consumers), which represents a 15 percent increase in price assuming a price of $6 per pack. Given our estimate of a price elasticity of –0.065, a 15 percent increase in price will result in 410,000 fewer smokers and a decrease in the number of packs consumed of 150 million. Total cigarette spending will go up by $15.15 billion per year because of the tax and price increase. Now assume that every person who quits smoking lives nine years longer as a result (an assumption consistent with the academic literature), so the tax increase results in 3.7 million extra life years. At what cost did the tax achieve this gain in life years? If we assume that the average smoker is 40 years old and lives until 69 (instead of 78), the total increase in expenditure as a result of the tax increase is $439.4 billion (29 × $15.15 billion), or $119,000 per life-year. The $119,000 figure is above the $100,000 per life year that is commonly used to decide whether a drug or medical treatment is sufficiently cost-effective to be recommended for use. Clearly, raising cigarette taxes is not the public health windfall claimed by anti-smoking advocates.

To summarize, most states have raised their cigarette taxes substantially in recent years, with 47 states increasing the cigarette tax a total of more than 110 times since 2002 and the federal government implementing a large increase in the federal tax in 2009. Cigarette taxes represent approximately $2.50 of the $6 price of cigarettes. While smoking has declined as a result of the tax, our recent study shows that the “core” of smokers that remains after the multiple recent tax increases is less responsive to price increases than commonly assumed. As a result, the public health argument to justify additional cigarette taxes is less valid today. Indeed, back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that cigarette tax increases are not a cost-effective way to improve health according to conventional guidelines. Cigarette taxes also represent a non-trivial burden on low-income families’ budgets.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.