By any measure, US federal regulation is big business. Year after year, hundreds of thousands of employees at 70-plus regulatory agencies churn out thousands of new rules. Since 1970, the number of restrictions in the Code of Federal Regulation (CFR) has increased, on average, 3.2 percent per year. Touching all aspects of American life, the CFR surpassed one million restrictions in 2016, and shows no signs of stopping.

With this level of continuous activity, it may seem paradoxical to say that there is a threshold standard—necessity—that every new regulation is supposed to adhere to. And yet, there is. Executive Order 12866, issued by President Bill Clinton in 1993 and affirmed by every president since, describes the two-step philosophy applicable to all federal regulation: first, a regulation must be necessary and, second, it should be crafted in a manner that maximizes net benefits.

From time to time, US presidents bemoan unnecessary rules and try to do something about it. In his 1980 Economic Message to Congress, Jimmy Carter stated, “I have vigorously promoted a basic approach to regulatory reform: unnecessary regulation, however rooted in tradition, should be dismantled and the role of competition expanded.” In a 1981 address to Congress, Ronald Reagan vowed, “We will eliminate those regulations that are unproductive and unnecessary by executive order where possible and cooperate fully with you on those that require legislation.” George H.W. Bush wrote in a 1992 memorandum to agency heads, “We must be constantly vigilant to avoid unnecessary regulation and red tape.” In a 1995 speech on regulatory reform, Clinton said: “We do need to reduce paperwork and unnecessary regulation. I think government can discard volume after volume of rules.” George W. Bush initiated a program to eliminate unnecessary mandates on the manufacturing sector. Barack Obama vowed in a 1992 Wall Street Journal op-ed to get rid of “absurd and unnecessary paperwork requirements… .We’re looking at the system as a whole to make sure we avoid excessive, inconsistent and redundant regulation.” Donald Trump considered himself a deregulator and required the elimination of two existing regulations for every new regulation.

Rationales for regulation / In essence, each of those presidents vowed to limit regulation to no more than what is necessary. But what does it mean for a regulation to be necessary? According to EO 12866, a new rule is necessary if it is “required by law, necessary to interpret a law, or made necessary by a compelling public need, such as material failures of private markets to protect or improve the health and safety of the public, the environment, or the well-being of the American people.” The EO also lists 10 principles for federal regulation, with the first three related to the rationale for a new rule: identify the problem the regulation is intended to address and the significance of the problem, determine whether existing regulations contributed to the problem, and identify and assess alternatives to direct regulation.

This standard allows us to identify the rationale for any new rule simply by examining the administrative record. What is the problem the regulation is intended to address? Is it required by statute or necessary to interpret a statute? Is it necessary to address a market failure? Is it necessary to address some other compelling public need? Is it necessary to correct a flaw with an existing regulation? Have alternatives to regulation been considered?

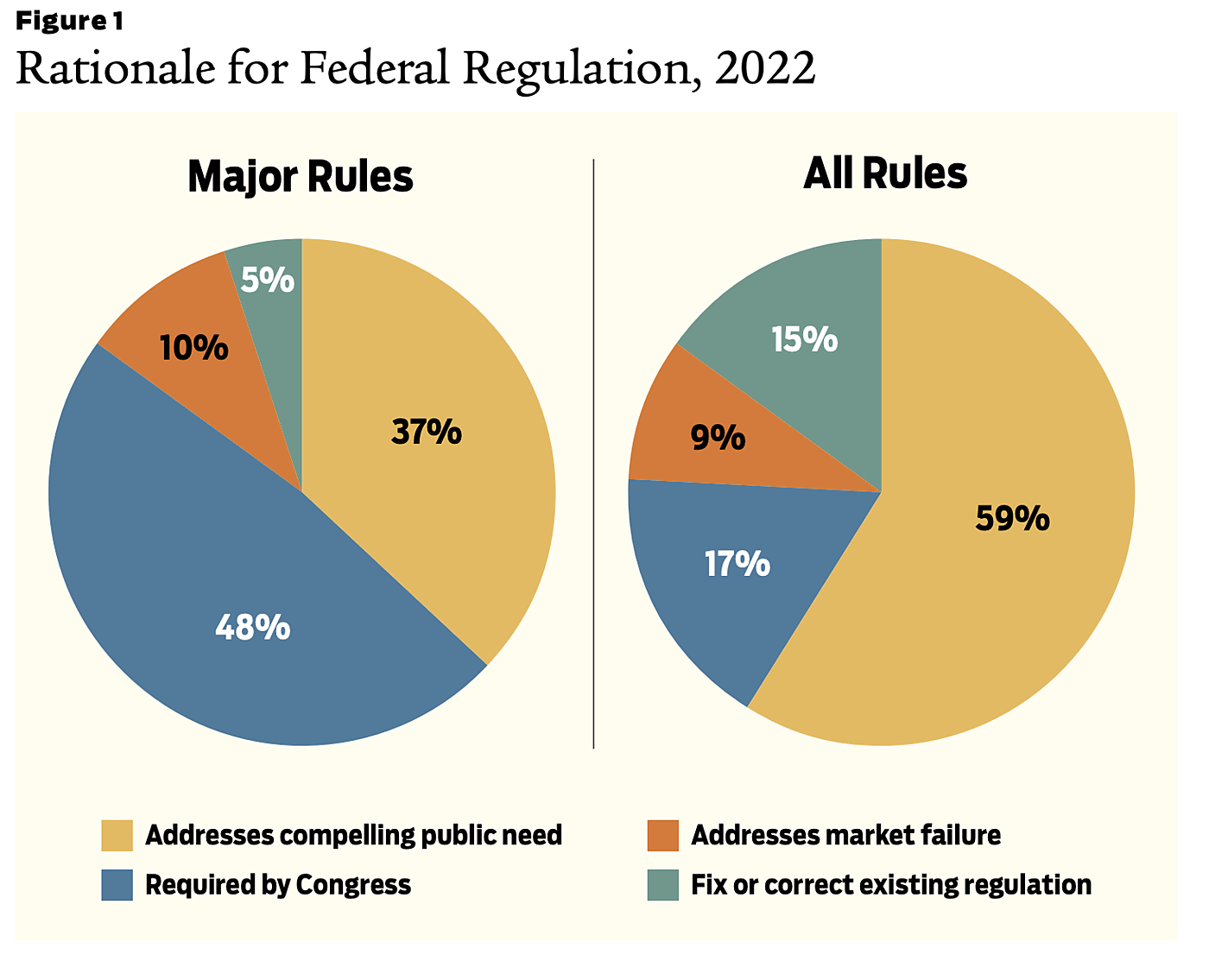

To answer those questions, we took a random sample of 340 of the 3,168 rules promulgated in calendar year 2022 and classified them by rationale. Our analysis is accurate to within 5 percent. We also classified all 80 rules designated as “major” by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (e.g., having an estimated annual economic impact of at least $100 million). We developed criteria to ensure consistency in our classifications, such as choosing “required by Congress” when another rationale (e.g., “addresses market failure”) was equally plausible. Because this analysis is based on a single year, 2022, it may not be accurate for other years or for a longer period; however, we have no reason to believe that 2022 would be significantly different from other years. The results of this exercise are shown in Figure 1.

Insights / Several conclusions can be drawn from this analysis:

- Agencies consistently specify the underlying policy problem. In every rule we reviewed, the underlying policy problem is clear from a reading of the preamble to the final rule. For example, Customs and Border Protection issued a rule to restrict imports of certain archeological material per an international agreement between the United States and Albania protecting cultural property. The Environmental Protection Agency added certain chemicals to its Toxic Release Inventory (which requires companies to report emissions) because Congress directed it to do so in the National Defense Authorization Act. The Coast Guard restricted boating in a small section of the Ohio River on August 28, 2022, to allow swimmers to participate in the Great Ohio River Swim in Cincinnati.

- Congress plays a minor role in initiating new rules. By definition, a statutory requirement for an agency to issue a rule leaves regulators with no discretion: they must comply. In such cases, it is Congress that determines the necessity of a new rule. For example, the Fish and Wildlife Service listed the Panama City Crayfish as a threatened species and designated its critical habitat, the Federal Aviation Administration issued an airworthiness directive to require replacement of a bent control rod within the gust lock system on certain British Aerospace aircraft, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission increased civil penalty amounts to account for inflation. Overall, Congress was directly responsible for 17 percent of all new rules promulgated in 2022.

- Regulators play the major role in initiating new rules. By far the most common rationale is a desire by regulators to address a compelling public need, a catch-all category where no single objective rises to prominence. For example, the Coast Guard issued rules to restrict boat traffic to allow fireworks displays over navigable waters on the Fourth of July. The Bureau of Industry and Security added to its export control list certain software used for automated geospatial imagery classification based on a determination by the Commerce, Defense, and State Departments that it would provide a military or intelligence advantage to the United States. In total, regulators used their discretionary authority in 59 percent of all rules issued in 2022.

- Some rules are intended to make markets more efficient. A market failure arises when markets cannot ensure an efficient outcome, potentially justifying government intervention. Market failures include externalities (when market transactions cause harm to people who are not buyers or sellers), asymmetric information (e.g., when sellers have important and relevant information not disclosed to buyers), and market power (e.g., a monopoly). In addition, so-called public goods (goods that are both non-excludable and non-rivalrous, such as national security) will be underprovided absent collective action, warranting government provision. Examples include the Interior Department setting limits on fishing or hunting to manage natural resources (public good), the EPA setting limits on air or water pollution (externality), and the Federal Trade Commission ensuring that consumers are adequately informed (asymmetric information). Overall, 9 percent of new rules address a market failure.

- Some rules are intended to correct or update an existing regulation. For 15 percent of all final rules, the purpose is to update or correct an error in an existing regulation. Such rules can be considered necessary. For example, in 2022, the Food and Drug Administration amended its medical device regulations to include an up-to-date mailing address, the FAA fixed a typographical error in a previous airworthiness directive, and the EPA removed Maine from the Ozone Transport Region based on Maine’s progress in reducing smog.

- Regulators rarely acknowledge that they considered alternatives to regulation. Although EO 12866 instructs agencies to consider alternatives to direct regulation, we found scant evidence of this in our sample of final rules. An exception was the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), which issued a rule limiting the pull strength of some magnets to reduce the risk of harm if they were ingested by small children. In the preamble to the final rule, the CPSC describes several existing voluntary standards it considered and rejected before choosing to issue the rule. However, in only 1 percent of final rules does an agency acknowledge it considered alternatives to regulation. To be fair, we did not review proposed rules, in which an agency could have described alternatives it considered and rejected before later issuing a final rule.

Congress and major rules / We went into this exercise intending to discern if major rules—the most impactful rules—are any different from other rules. Figure 1 compares the results for all rules versus major rules. One difference stands out. Whereas Congress played a minor role in directing regulators to issue a rule generally, it is in the driver’s seat for major rules: nearly half of major rules are required by statute or made necessary to interpret a statute.

This finding may soon become important. The current lineup of the US Supreme Court, where conservatives hold a 6–3 majority, is already influencing the administrative state. And there is more to come. In its current term, SCOTUS is expected to rule on cases where the discretion of regulators is front and center: the non-delegation doctrine, the major questions doctrine, and Chevron deference. Its decisions could have decades-long ramifications on the rationale for new rules.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.