In the US wireless communications market, antitrust regulators blocked so-called four-to-three mergers—mergers of two of the four largest competitors—in 2011 and 2014. But authorities did allow then-No. 3 carrier T‑Mobile to acquire then-No. 4 Sprint in February 2020, after T‑Mobile agreed to several conditions. The merger was, and remains, the subject of intense debate over its effects on consumers.

That debate can now be informed with empirical evidence on post-merger consumer prices and market competition. Those data tell an impressive story: Retail mobile subscription prices, network investment, service quality, market shares, and industry profits in the US mobile communications industry strongly support the thesis that the merger produced substantial consumer gains. This is despite the failure of the government “remedy” of nurturing the emergence of a new fourth major network that was supposed to mitigate market power in the sector.

The T‑Mobile/Sprint Merger

In April 2018, T‑Mobile announced that it would buy Sprint for $26.5 billion. The proposed acquisition was challenged by the Antitrust Division of the US Justice Department because it would reduce the number of national mobile operators from four (including Verizon and AT&T) to three, further concentrating the market and causing potential harm to consumers.

In July 2019, however, the Justice Department approved the merger with conditions. In the settlement, T‑Mobile agreed to sell Sprint’s prepaid wireless business, Boost Mobile, and a significant number of cellular spectrum licenses to DISH, a satellite TV carrier that had previously acquired a substantial number of wireless licenses. The transactions were mandated to allow DISH to create and operate a new fourth national wireless network. In November 2019, the Federal Communications Commission, approved the requisite license transfers needed for the T‑Mobile/Sprint merger. The following February, the merging parties won a favorable verdict in an antitrust suit brought by 10 states to block the deal, and T‑Mobile and Sprint closed their transaction on April 1, 2020.

The merger was controversial from the outset. Critics believed the deal would turn T‑Mobile from a “maverick” firm with a history of disrupting the mobile market into a sleepy incumbent cooperating with Verizon and AT&T, its remaining rivals, to restrict output and raise quality-adjusted prices. Even after the transaction was consummated, academics Melody Wang and Fiona Scott Morton condemned the transaction, writing: “the tmobile/sprint deal will go down as one of the worst merger-enforcement decisions in decades” (emphasis in original).

Those favorable to the combination, on the other hand, saw the merger as instrumental in allowing T‑Mobile to achieve important efficiencies through the acquisition of Sprint’s substantial spectrum assets. With these additional inputs, T‑Mobile could more rapidly deploy advanced fifth generation (5G) cellular network technology and upgrade its network coverage and performance.

Consolidation of the Wireless Industry

The T‑Mobile/Sprint merger was the culmination of a consolidation of the US wireless industry that had begun more than two decades before. Historically, the US market was highly deconcentrated on a national scale because wireless licenses were issued across hundreds of local coverage areas. This policy was in contrast with virtually all other countries, which issue (large) regional or national licenses.

Consolidation was inevitable if network operators were to exploit the available economies of scale and geographical scope. By 2001, through a process of license aggregations in auctions and secondary market mergers, the mobile market evolved into six major national networks. That total was reduced to four by 2005: Cingular (after acquiring AT&T Wireless in 2004 and adopting its corporate name), Verizon, Sprint (after acquiring Nextel in 2005), and T‑Mobile, listed by size. Those mergers increased the US mobile sector’s Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) measuring market concentration; the nationwide HHI (population-weighted across local markets) rose from 2,450 in 2000 to 2,706 in 2005.

This consolidation did not suppress wireless market growth nor, concomitantly, raise retail prices. To the contrary, technology adoption followed major combinations, particularly in the upgrade from 2G to 3G technology in the mid-2000s, which appeared causally related to the Cingular/AT&T Wireless and Sprint/Nextel mergers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index (CPI‑U) component for wireless services declined by nearly 60 percent in nominal terms between the first quarter of 1999 and the first quarter of 2018, the eve of the T‑Mobile/Sprint merger, while quality of service rose markedly.

After 2005, however, it appeared to regulators that the industry had settled into a stable oligopoly, with the two largest firms, Verizon and AT&T, leading the market. Sprint (at that time, the third largest) and T‑Mobile (fourth) were seen as relatively weak. As a result, the FCC denied AT&T’s 2011 bid to buy T‑Mobile, concluding that a merger of the second- and fourth-largest mobile networks would have created, in the words of a 2011 FCC staff report, the “nation’s largest wireless provider…, giving it two-and-a-half times the size of the third largest.” That would have resulted in “an increase in both subscriber and spectrum concentration that is unprecedented in its scale” and, speaking of T‑Mobile, meant the “elimination of a nationwide rival that has played the role of a disruptive competitive force.”

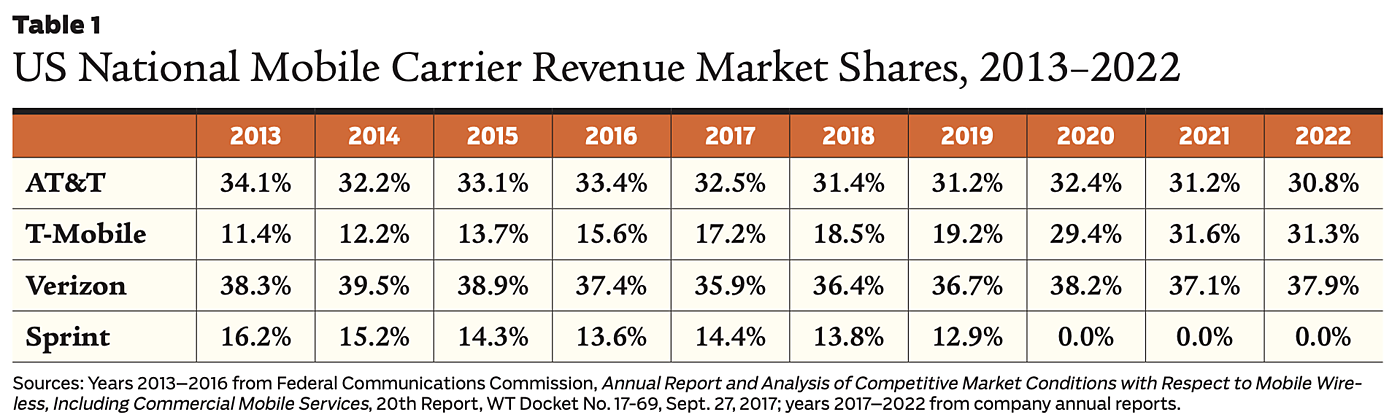

Subsequently, T‑Mobile continued to be that disruptive force, branding itself the “Un-carrier” while introducing an array of product and marketing changes. This was bolstered by T‑Mobile’s 2013 acquisition of the country’s fifth largest carrier, MetroPCS. The merged enterprise did not slow its disruption nor restrict output; the post-merger T‑Mobile gained more subscribers than any of its rivals, leapfrogging Sprint to become the industry’s third largest carrier. (See Table 1.) Sprint, on the other hand, went into decline, but it had a wealth of bandwidth, which enticed T‑Mobile to bid to acquire it in 2018. Meanwhile, Verizon and AT&T enjoyed stable industry positions as the top two firms in market share.

Ensuing Controversy

The T‑Mobile/Sprint merger presaged a marked increase in industry concentration. Based on the 2018 market shares for subscriber data, the nationwide HHI was calculated at about 2,631 prior to the merger; the HHI immediately post-merger jumped to 3,045 according to an estimate by the wealth management firm Bernstein & Co. Such increases are suspicious to antitrust authorities. Combinations resulting in HHI above 2,500 and increasing the index by more than 200 were “presumed to be likely to enhance market power” under the Antitrust Division/FTC merger guidelines.

The key argument for the T‑Mobile/Sprint combination was that T‑Mobile’s maverick competitiveness would be enhanced by the acquisition of Sprint’s bountiful spectrum assets that Sprint had been using ineffectively. This acquired spectrum would enable the new T‑Mobile to supply enhanced mobile coverage and higher network access speeds, intensifying its rivalry with Verizon and AT&T.

Opponents argued that the merger would sharply increase market concentration, leading to restriction of output, higher prices for consumers, and diminished innovation incentives. Several noted economists voiced concern about the efficiency outcome of the consolidation, predicting a reduction in competition in both prepaid and postpaid services.

This criticism continued post-merger. As noted above, Wang and Scott Morton characterized the transaction as a “debacle” in the University of Chicago online publication ProMarket, asserting that it had resulted in rising cellular retail prices that were harming consumers:

Not even two years later, [Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust Makan] Delrahim’s plan is already falling apart … and price-conscious consumers are bearing the brunt of harm from the merger’s fallout… .

These frustrations have fueled heated criticism of the merger. Such critiques are well-placed, as the merger has already produced harm and threatens to wreak more damage… .T‑Mobile has also signaled to investors that it has become more like its rivals Verizon and AT&T. On an investor call in February, CEO Mike Sievert said, “We’ve competed mostly on price in the past, if we’re honest. Now, we have a premium product.”

Translation: The era of aggressive price competition in wireless is over. Looking forward, we can expect T‑Mobile, AT&T, and Verizon to nestle into a cozy triopoly that returns immense profits to their shareholders.

Now, four years after the T‑Mobile/Sprint merger, it is an opportune time to examine the empirical evidence. Has the merger worsened consumer outcomes? Or has the aggressive “Un-carrier” been enabled in its aggressive pursuit of customers?

Empirical Evidence on Consumer Welfare

To assess the effects of the merger, we consider three hypotheses:

- The merger would result in higher industry-wide prices.

- Industry profits would increase, post-merger, for the three national carriers.

- DISH would not develop into a meaningful competitor.

Consumer prices / We first examine price trends for the US mobile market using series calculated by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics: One is part of the Consumer Price Index (CPI‑U), and the other is part of the Producer Price Index (PPI). The former series reflects prices paid by consumers, while the latter reflects prices charged by carriers. According to the BLS’s website, the two “significant differences between the wireless telecommunications index of the PPI and the Consumer Price Index (CPI)” are:

- “The indexes published by the CPI are inclusive of retail taxes. The PPI does not include these taxes.”

- “The CPI publishes indexes using urban data only, whereas the PPI includes data from rural as well as urban areas.”

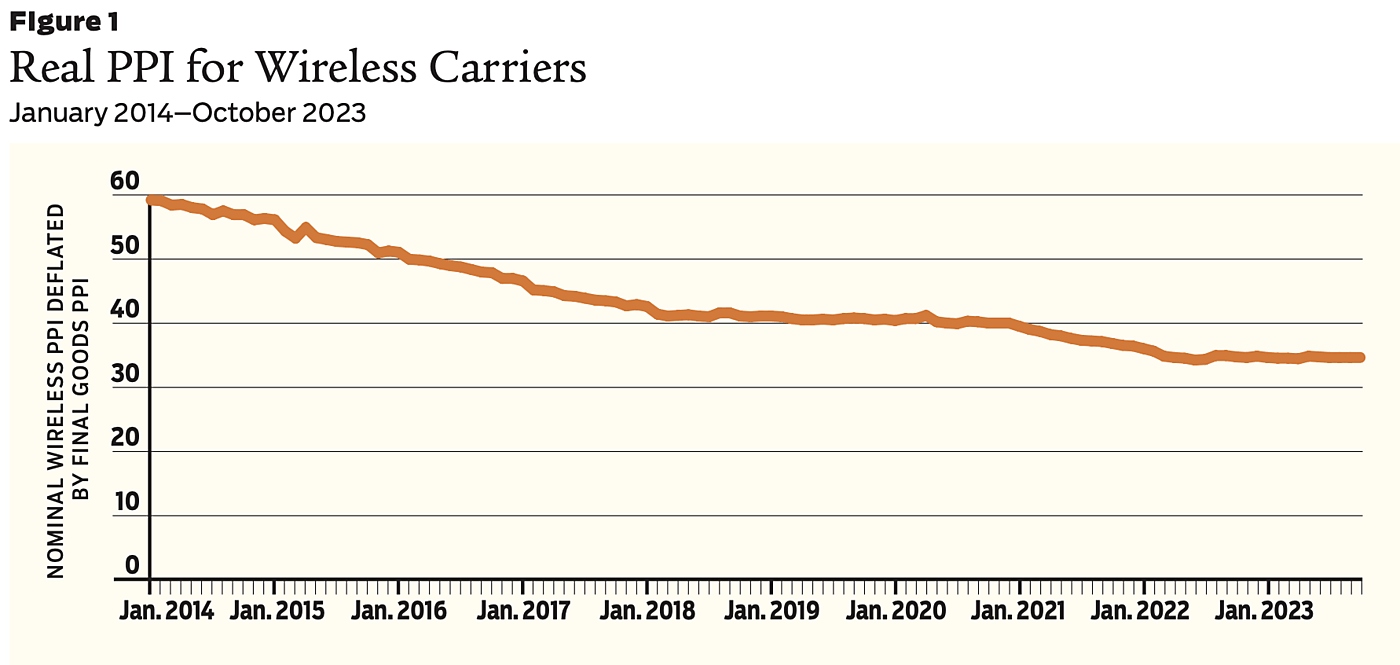

Hence, the PPI is more inclusive and offers a cleaner picture of prices charged by the mobile carriers by excluding retail taxes. This is a considerable advantage in investigating the issue of market power because taxes are not imposed by the carriers but by governments, and such charges are both large and (year-to-year) variable. We thus focus on the PPI series (PPI—Wireless Carriers, Not Seasonally Adjusted) and deflate it by the overall PPI index to produce the trend in real prices. (The other available PPI series and the CPI display trends very similar to the pattern presented here.)

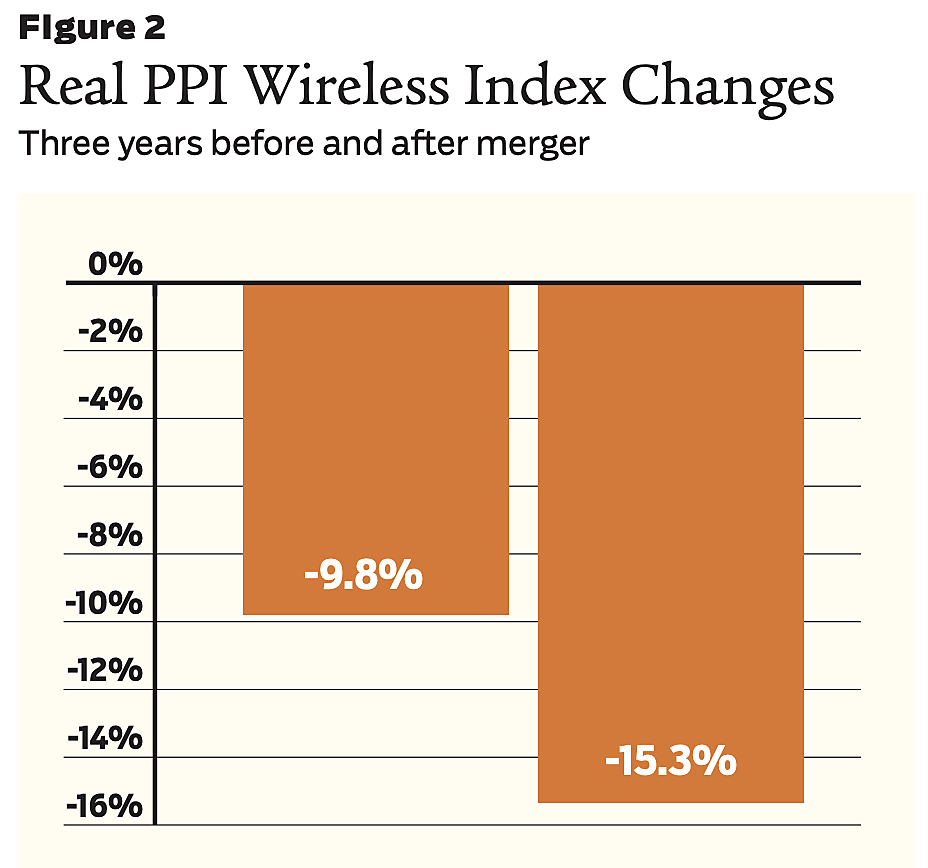

We find that strong real price reductions followed the T‑Mobile/Sprint merger, exceeding the real price declines pre-merger. Those price reductions can be summarized in the real wireless price changes for three-year intervals preceding the merger (March 2017 to March 2020) and following the merger (March 2020 to March 2023). Figure 1 displays the real trend in prices, with the PPI wireless series deflated by the overall PPI index. Figure 2 summarizes these data trends. The price level declines 9.8 percent in the pre-merger period and 15.3 percent in the post-merger period. This reveals over a 50 percent increase in the decline following the consummation of T‑Mobile/Sprint.

Service quality / What about quality? Might carriers have reduced network investment, thereby providing consumers with poorer service after the 2020 consolidation?

Wireless network investment / The post-merger decline in prices could have been due to a decline in service quality. Wireless firms may have slowed investment in costly inputs, increasing profits by effectively raising quality-adjusted prices to subscribers even as (inflation-adjusted) subscription fees were flat or declining. This hypothesis, however, conflicts with the evidence.

The 2018–2021 investment profile for US mobile networks shows that T‑Mobile more than offset any decline in reported capital spending from the elimination of Sprint: the national US wireless carriers invested $63.5 billion in the two-year period 2020–2021, up from $58.9 billion in the two-year period 2018–2019. T‑Mobile, alone, increased its capital spending from $5.9 billion in 2019 to $12.1 billion in 2021 (following the merger). The wireless industry’s share of total U.S. corporate capital expenditure (adjusting for inflation as well as other macroeconomic trends) did not decline, but rather rose slightly, from 0.66 percent in 2018–2019 to 0.68 percent in 2020–2021, according to UBS Investment Research.

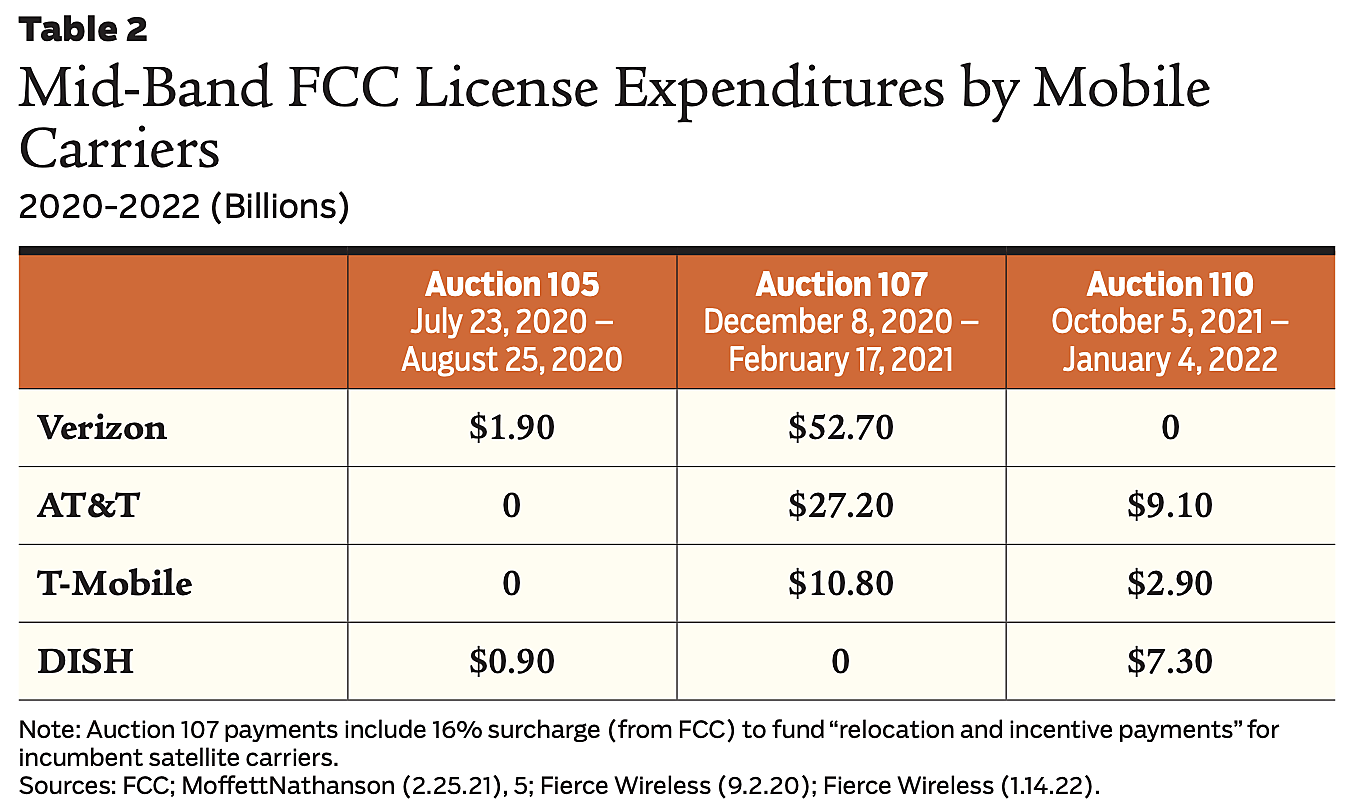

Reported capital investment flows exclude purchases of radio spectrum assets in the form of FCC licenses. The purchase of such licenses, however, creates long-lived input streams complementary to network infrastructure. Through its acquisition of Sprint, T‑Mobile increased its spectrum portfolio from 109.7 MHz to 298 MHz, far surpassing Verizon and AT&T’s spectrum holdings of 148.3 MHz and 114.9 MHz, respectively. In response, AT&T and Verizon bid aggressively in the FCC’s 2020–2022 spectrum auctions. (See Table 2). This expensive strategy was necessitated, as reported extensively by industry analysts and in the trade press, by T‑Mobile’s accelerated rollout of 5G. The pattern of rivalry to implement network upgrades is the reverse of what would be observed in the presence of “coordinated effects” to reduce competition post-merger.

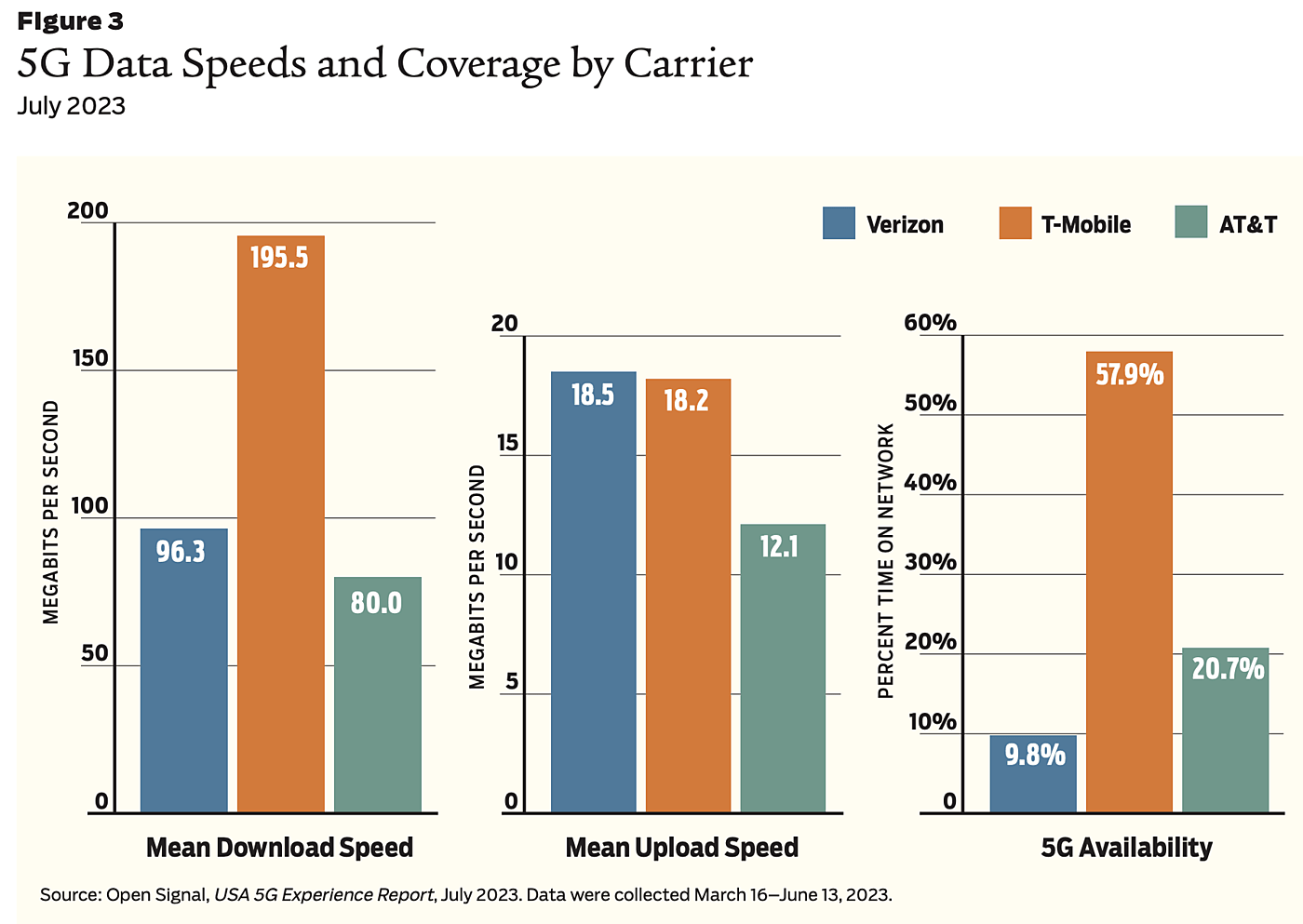

Download speeds and 5G coverage / In the years prior to the merger, T‑Mobile struggled to take market share from Verizon and AT&T because of perceived advantages in network coverage and service quality for the two larger systems. In the aftermath of the merger with Sprint, the new T‑Mobile quickly achieved more than parity in those product characteristics. This achievement was linked to the rollout of 5G. By mid-2023, T‑Mobile could reach half of its customers via 5G while fewer than 10 percent of Verizon subscribers and only 20 percent of AT&T’s customers accessed 5G. See Figure 3.

The capacity afforded by Sprint’s large cache of mid-band spectrum had given T‑Mobile an instant advantage in deploying the new network. In July 2023, Open Signal reported that 5G mean download speeds on T‑Mobile’s US network had rapidly improved and were more than twice as fast as Verizon’s and AT&T’s.

Carrier profitability / A monopolistic transaction restricts output and raises prices, categorically rewarding firms in the industry. Alternatively, a pro-competitive merger may result in higher profits for the firm (or firms) driving new efficiencies, while those gains pose challenges for rivals. In the latter case, profits rise for the firm achieving competitive superiority, while less innovative industry incumbents lose value. This outcome implies an improvement in consumer welfare as competition drives down quality-adjusted prices.

In the years preceding the merger, T‑Mobile aimed to overcome its position as a small carrier with a weak network. It implemented its “Un-carrier” strategy and grew so rapidly in subscribership that the network became bandwidth-constrained. Additional spectrum inputs were key to its continued growth. Sprint’s considerable spectrum portfolio was the driver of T‑Mobile’s demand to acquire the network; Sprint’s 54.5 million mobile customers may have been an afterthought.

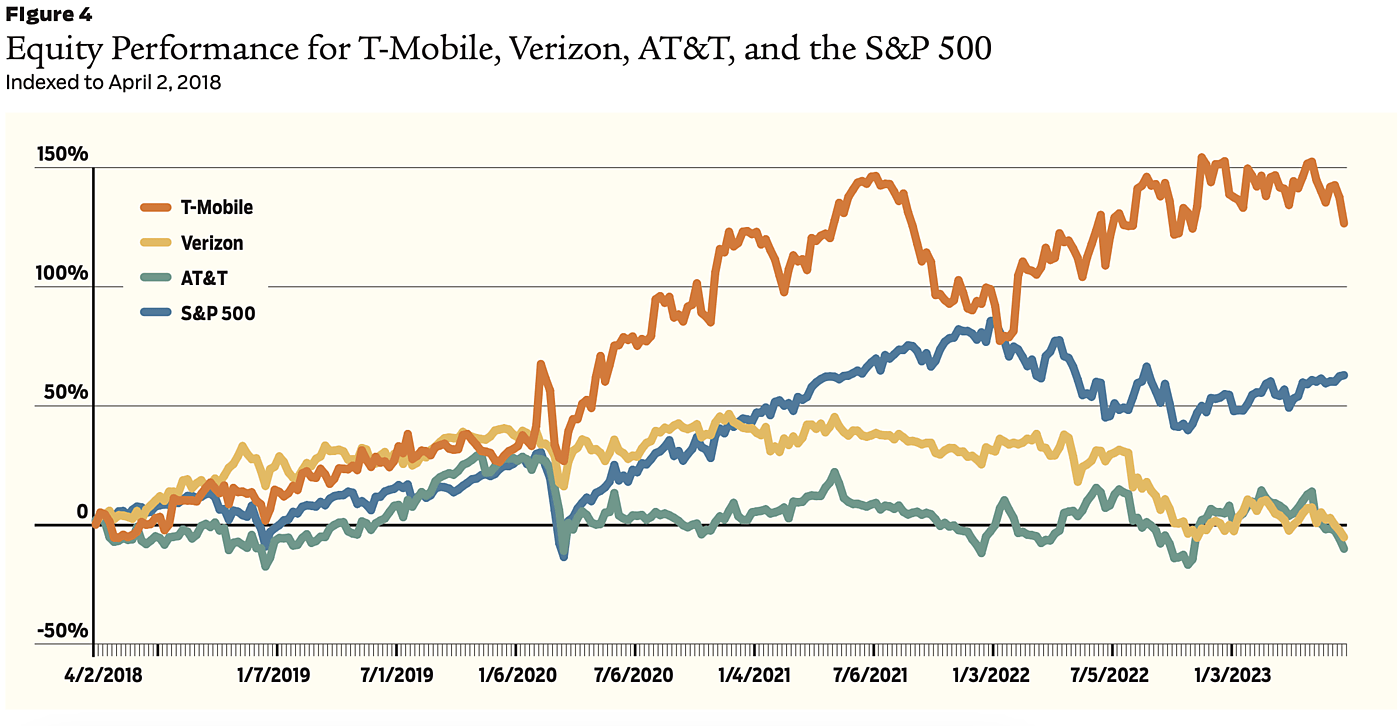

Financial markets revealed the startling results of the restructuring of the US mobile market. Over the April 1, 2018–May 31, 2023, period—during which the merger was announced, approved by regulators and a federal court verdict, and then consummated—T‑Mobile shares gained 124.9 percent, unadjusted, which amounted to 42.1 percent market-adjusted (i.e., above concurrent S&P 500 Index returns, which were themselves strong, with 58.3 percent growth). Over the same period, absolute returns for Verizon and AT&T were both negative; adjusted for S&P 500 returns, Verizon was –39.6 percent and AT&T was –43.7 percent (using dividend and split-adjusted stock prices from Yahoo!Finance). See Figure 4.

Ironically, much of T‑Mobile’s success derives from US antitrust policy. As Sprint looked for a buyer, three national carriers could have bid for it: AT&T, T‑Mobile, and Verizon. But any acquisition by AT&T or Verizon surely would have been blocked by authorities. Thus, T‑Mobile faced light bidding competition and acquired Sprint and its generous cache of radio spectrum at a bargain price.

T‑Mobile acquired 174.3 MHz of nationwide mobile spectrum (population-adjusted by market, MHz-pop) through the merger, paying $40.8 billion for Sprint and its spectrum holdings. Even if the rest of Sprint’s vast network assets were worthless, this implies a price for “bandwidth” equal to 65¢ per MHz-pop, far below the $1.10 that AT&T, Verizon, and other firms paid for C‑Band satellite licenses in FCC auctions ending in early 2021.

However the post-merger industry triopoly is characterized, it surely has not been “cozy.” T‑Mobile’s post-merger supranormal returns contrast vividly with the below-market returns realized by Verizon and AT&T. By November 2022, T‑Mobile’s market capitalization had surpassed both AT&T’s and Verizon’s, as it increased market share and developed its 5G network to accommodate new traffic and applications. This pattern is consistent with the theory that the merger delivered efficiencies to the acquiring company, T‑Mobile, and inconsistent with the theory that it led to reduced output and higher industry prices.

DISH / The opponents of the merger were correct in one respect: the merger settlement with the DOJ has not been successful in establishing DISH as a fourth national wireless competitor. The divestiture of T‑Mobile’s prepaid wireless subsidiary to DISH and the requirement that T‑Mobile sell some of its wireless licenses to DISH were intended to nurture a viable fourth facilities-based competitor to replace the exiting Sprint. However, DISH’s platform has been losing wireless market share rapidly in the post-merger period. Meanwhile, its satellite pay-TV business has also declined. Despite being favored with preferential access terms for its wireless resale operations and enjoying favorable prices when it acquired T‑Mobile/Sprint spectrum assets in the divestiture, DISH equity shares have plummeted, from $36.86 on April 25, 2018, to $6.71 on May 30, 2023, a decline of 82 percent.

It is implausible that DISH supplies significant competitive constraint in the wireless industry. Nevertheless, market rivalry has increased, revealing the irrelevance of the Justice Department’s attempted remedy.

Conclusion

The evidence that has accumulated since the consummation of the T‑Mobile/Sprint merger is clear: T‑Mobile’s acquisition of Sprint’s spectrum has led to substantial improvement in consumer welfare. Post-merger, T‑Mobile has led the way in deploying 5G, thus increasing service quality while driving down real consumer prices. This has caused T‑Mobile’s share price to soar while other mobile carriers’ equity values sharply declined. Those rivals have responded by spending aggressively to improve their networks.

The “cozy triopoly” that merger critics feared has not emerged. Consumers have benefited from an increase in wireless competition, even though the T‑Mobile/Sprint merger has increased concentration by reducing national US mobile networks from four to three.

Readings

- Demsetz, Harold, 1973, “Industry Structure, Market Rivalry, and Public Policy,” Journal of Law and Economics 16(1): 1–9.

- Eckbo, B. Espen, 1983, “Horizontal Mergers, Collusion, and Stockholder Wealth,” Journal of Financial Economics 11(1–4): 241–273.

- Federal Communications Commission, 2011, “Staff Analysis and Findings,” WT Docket 11–65.

- Hazlett, Thomas W., 2017, The Political Spectrum: The Tumultuous Liberation of Wireless Technologies, from Herbert Hoover to the Smartphone, Yale University Press.

- Wang, Melody, and Fiona Scott Morton, 2021, “The Real Dish on the T‑Mobile/Sprint Merger: A Disastrous Deal from the Start,” ProMarket, University of Chicago, Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State, April 23.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.