In an interview for CNN in March, Dr. Deborah Birx, who was the Trump administration’s coronavirus response coordinator, offered a remarkable appraisal of that administration’s efforts to contain the virus:

I look at it this way: The first [few months] we have an excuse. There were about a hundred thousand deaths that came from that original surge. All of the rest of them, in my mind, could have been mitigated or decreased substantially if we took the lessons we had learned from that moment. That’s what bothers me every day.

Her comments quickly drew fire. USA Today editorialized: “Why is she telling us now? And why did Birx persist in her high post, delivering a business-as-usual message, while she knew of so much needless death?” Jonathan V. Last, editor of the Trump-critical The Bulwark, wrote of Birx, “You should be … haunted by what happened on your watch and shamed and shunned by every peer in your profession, for the rest of your days.” Critics quickly posted video of her praising Trump’s response to the virus when he was still in office, including her telling the conservative network CBN: “He’s been so attentive to the scientific literature and the details and the data. I think his ability to analyze and integrate data that comes out of his long history in business has really been a real benefit during these discussions about medical issues.”

To be sure, fair criticisms can be leveled at the Trump administration’s response to the disease. But Birx’s remaining in Trump’s good graces allowed her to make recommendations under the mantel of being his COVID adviser. During the final months of his presidency, she spent most of her time on the road, traveling from state to state, meeting with governors, university presidents, public health officials, and reporters. She delivered an urgent message to everyone who would listen: COVID is surging; it’s insidious and dangerous; and people need to start guarding against it now.

Her travels create a unique opportunity to estimate whether people were heeding her advice. More specifically, the variation in where and when she made her recommendations can be compared to outcome variables such as whether people were wearing masks.

As you’ll see, the evidence convinces me that she saved thousands of lives. But she didn’t save lives everywhere: people were more likely to mask up after her visits, but only in states that Trump won in the 2020 presidential election. Being an emissary of his White House apparently grabbed those state residents’ attention and led some of them to wear masks. Governors were also more likely to listen to her in Trump-supporting states and reporters appeared to give more coverage to her visits to those states.

First and foremost, she urged everyone to wear facemasks. Birx always wore a medical mask, which became as ubiquitous as her scarves that the media constantly noted. Early in her travels, she talked about people needing to mask-up when they were “out and about.” As the weather turned colder and people moved inside, she broadened her message, urging everyone to wear masks whenever they were interacting with people outside of their immediate households — even in their own homes when friends, neighbors, and relatives were visiting.

She planted the message “Masks work” across the country like Johnny Appleseed planted trees. When nudged by reporters, she would describe studies of salon workers and airline passengers whose masks protected them from catching COVID. One of her favorite studies looked at the passengers of an international flight who were all tested for COVID prior to boarding, though the results were not instantly known. It turned out that eight of the passengers were infected, but none of the others caught COVID because everyone wore masks. Once, after adding a bit too much detail, she chuckled and said, “I won’t bore you with all the R-squared values.”

During the latter half of her trip, she would sometimes point to herself and say, “I’ve been on the road,” eating at restaurants and staying at hotels, and “I’ve stayed negative.” Like many early pioneers in medical research, she was experimenting on herself, testing whether wearing masks, social distancing, and washing her hands would protect her from the virus.

She had plenty of potential exposures. She interacted with thousands of people as she traveled more than 25,000 miles and visited 40 states, many of them more than once. On a radio show, she described standing in a hotel lobby within a few feet of an unmasked man in a state that had the highest number of new COVID cases per capita at the time. On the counter near them was a sign that said guests must be masked. A few days later, she sat in an hour-long meeting within six feet of a man who later tested positive for COVID.

The danger and drudgery would have been worthwhile if people were listening to her and heeding her advice. But were they? A local reporter in Rhode Island asked her, “Are you satisfied that your message is [being heard]?” Birx paused to reflect on his question, ultimately replying, “You know, I don’t think any of us in public health are ever satisfied.” She paused again, searching for the right words, and then enunciating slowly said, “We always want our message to be heard and internalized and utilized” by an ever-higher percentage of the intended audience.

Did Birx’s efforts have a positive effect? She must have thought so. A month after leaving Rhode Island, a reporter halfway across the country asked, “Knowing what you know today, if you were able to go back in time, say [to] February or March, what would you [have done] differently?” Without hesitation she said she would have hit the road earlier to stress the importance of adhering to the reopening guidelines following weeks of local and state government orders to shelter in place.

This begs the question of whether the Biden administration should now have someone like her visiting with governors and the American people to talk about receiving the COVID vaccine and taking care not to relax mitigation strategies too rapidly as the virus’s infection and death tolls fall. Warm weather and the vaccines have certainly curtailed the virus’s spread, but there is still elevated public health risk, exacerbated both by virulent new strains of the disease and a significant chunk of the public’s hesitancy (and in some cases outright opposition) to receiving one of the vaccines. An official filling the role Birx did last year would certainly be helpful. But will anyone undertake it, and will that person be able to effectively deliver the message to the people who most need to hear it?

Hard Recommendations Wrapped in Compliments

On her 2020 travels, often to state capitals and university towns, Birx typically began her days in private meetings with governors or university presidents, followed by (sometimes public) roundtable discussions, and culminating in press conferences. She won a bunch of trifectas where the governor came to all three, and was rarely snubbed entirely, though a prime counterexample was South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, who turned down repeated invitations to meet with her.

Birx often talked about “carrying messages” to the American people. She didn’t actually go door-to-door or hold large public rallies, of course, but she used the press and politicians as her megaphone. She almost always started her press conferences with compliments about what the governor or state residents were already doing to fight the virus. Then she would launch into “the data,” characterizing the severity and likely path of a state’s COVID outbreak using statistics like COVID cases per capita, positivity rates of tests, and hospital utilization rates. She might say that the COVID-test positivity rate of the state was high enough that the entire state was “red” or that such and such percent of its counties were “red.”

Then came recommendations. Wearing masks always topped the list. For example, in her Missouri press conference, she used the name-checking panache of a touring rock star to push the practice:

My fundamental message to everyone [is] that all of us across Missouri, whether you are in Kansas City or Saint Louis, whether you are in Springfield, Joplin, or Jefferson City, whether you are in Branson or at the Lake of the Ozarks, our job in each and every community is to decrease viral spread…. What does that mean? We need every American and everybody in Missouri to be wearing a mask and to be socially distancing.

A video clip of her delivering this quote was the lead story on that night’s newscast of the ABC affiliate in Saint Louis.

After the recommendations came the questions from the press. Most of the reporters threw her “softballs,” but some “hardballs” were mixed in. She swung hard at the former and mostly ducked the latter, which usually had the name “Trump” in them. Several times she was asked what she thought about Trump’s campaign rallies of densely packed, unmasked supporters. She would invariably say that she gives everyone, including the president, the same advice to wear a mask and then treated the question like a softball.

She did swing hard at a fastball on a visit to Utah. A reporter asked, sounding incredulous, “Are you saying that families in Utah should not get together with their extended families for Thanksgiving?” She didn’t mince her words, although they were a bit garbled: “At your current rate of rise [of COVID cases, that’s] correct.”

One press conference stands out from the rest. On her second trip to North Dakota at the end of October, she skipped the compliments and went straight to the data. The state was bright red; it had the highest number of new cases per capita in the country. She was more strident than usual, perhaps because she saw little mask-wearing after she checked out of her hotel that morning.

Reporting on what she had observed of residents as they went about their daily lives was a standard part of her spiel. In Alabama she saw many more women than men wearing masks; in her press conference there, she asked men to mask-up. At the University of Kentucky, she saw unmasked parents walking with their masked children; she asked parents to mask-up. What she saw in North Dakota was the “least use of masks” that she had seen anywhere on her trip. She insisted that everyone needed to wear a mask when in public or gathered with others.

Her comment about North Dakotans made headlines both nationally and locally. ABC News said she “called out” North Dakotans for their poor use of masks; CNN said she “slammed them.” It was the front-page headline of the Bismarck Tribune, which added that she had refused to “name the places she toured in Bismarck.”

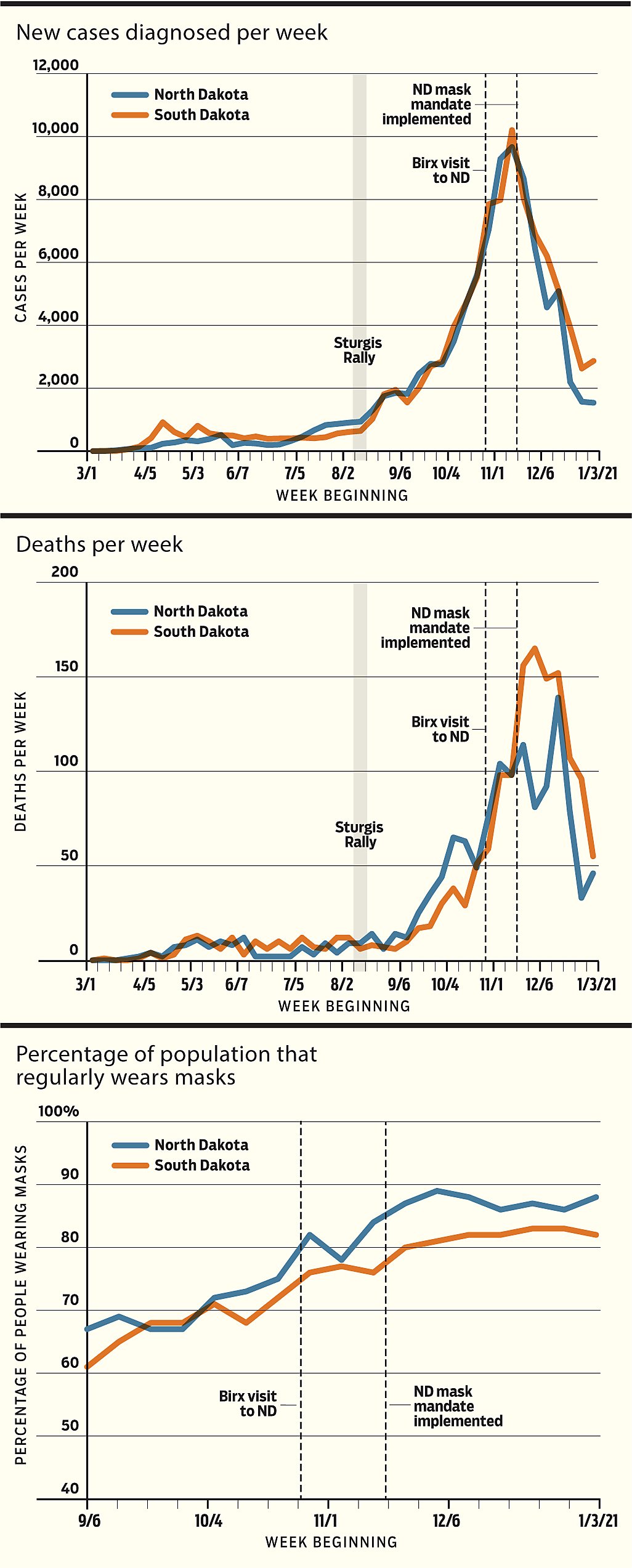

Figure 1 plots weekly estimates of mask usage by North and South Dakotans from a voluntary survey of Facebook users conducted by researchers at Carnegie Mellon. Figure 1 also plots the weekly number of COVID deaths and newly diagnosed cases in the two states. Birx visited North Dakota on October 26, 2020, as noted in Figure 1. During the week of her visit, 81.6% of North Dakotans surveyed said that they wore masks either “all the time” or “most of the time” when they were out in public places. A week after her visit, the number wearing masks decreased to 77.9%. It looks like wagging her finger at North Dakotans may have induced some of them to thumb their noses at Birx. But this was only one of many visits she made to different states, so we may get a very different result when we analyze more data.

The Two Dakotas: A Natural Experiment?

In many ways, North and South Dakota resemble identical twins. Residents’ attitudes and demographics are largely similar. Both have roughly three quarters of a million people and are mostly white. The two states have similar weather, similar urban/rural splits, and similar governors (both Noem and North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum are Republicans prone to wearing cowboy hats, boots, and blue jeans).

Identical twins separated at birth provide an iconic example of a natural experiment: two otherwise similar groups of people were differently affected by some factor in the “real world,” as opposed to experiments carried out by researchers in a laboratory. Ideally, we’d use more than two states to test our hypothesis — in the jargon of statistics, this analysis doesn’t have much power — so any conclusions we reach by looking at the data are not likely to be decisive. Still, comparing the two states can provide useful insight: it has the power to persuade, to help understand more sophisticated analyses, and to generate hypotheses.

Figure 1

A Natural Experiment in the Dakotas

Three differences between the Dakotas stand out: South Dakota held the 10-day Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in early August, Birx visited North Dakota but not South Dakota in late October, and only North Dakota imposed a statewide mask mandate, beginning in mid-November. In Figure 1, we can see changes in the states’ data relative to each other following each of those events.

Sturgis / The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally drew nearly a half a million riders to a small county in South Dakota. Many of the riders packed closely together at restaurants, concerts, motorcycle races, and bike shows. Few wore masks. Thousands of those visitors came from North Dakota, so it isn’t a valid control group. About all we can say from looking at Figure 1 is that there was a surge of cases and deaths in both Dakotas in the four months following the rally.

A recent academic paper, “The Contagion Externality of a Superspreading Event,” analyzed the Sturgis rally as a natural experiment by grouping counties across the country by whether or not some of their residents — actually, their cellphones — went to Sturgis. The authors found that the number of COVID-19 cases in the two weeks following the rally increased significantly faster in the rider-sending counties than non-rider-sending ones. According to their results, the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally was a superspreading event that sparked between 115,000 and 265,000 additional cases of COVID-19.

South Dakota Governor Noem dismissed the analysis, saying the authors just “made up some numbers and published them.” The economists’ work isn’t ironclad but they didn’t make up the numbers: their methodology is solid and I believe their results. Indeed, their report makes me grateful that my own Republican governor, Mike DeWine of Ohio, canceled the Arnold Sports Festival in Columbus on March 3, 2020.

Mask mandate / The Dakotas also differed on whether they implemented a statewide mask mandate. North Dakota Governor Burgum surprised nearly everyone by announcing a mandate on November 13 that went into effect the following day. Governor Noem is one of 11 governors who chose not to implement a statewide mask mandate.

In Figure 1, look at the mask usage curves on either side of the imposition of the North Dakota mandate. The vertical gap between North and South Dakota became larger after the mandate, suggesting the mandate prompted North Dakotans to wear masks more often.

But did the mandate prevent COVID cases and deaths? Interpreting these data has “emerged as a kind of Rorschach test for the effectiveness of mask mandates,” according to Adam Willis, a young reporter at the Fargo Forum newspaper. Opponents of mask mandates look at the curves and see only that South Dakota’s curves decrease alongside its neighbor’s. They see a government intervention that’s constraining their liberties while the health effects of COVID did nothing that wouldn’t have happened anyway. Proponents look at them and see North Dakota’s curves decline more steeply. They see a government intervention that effectively coaxed people to protect themselves and others, saving lives. But again, you can’t resolve this debate by looking at the curves of just these two states; you need more test subjects. We’ll consider just such evidence later in this article.

Suasion vs. Finger-wagging

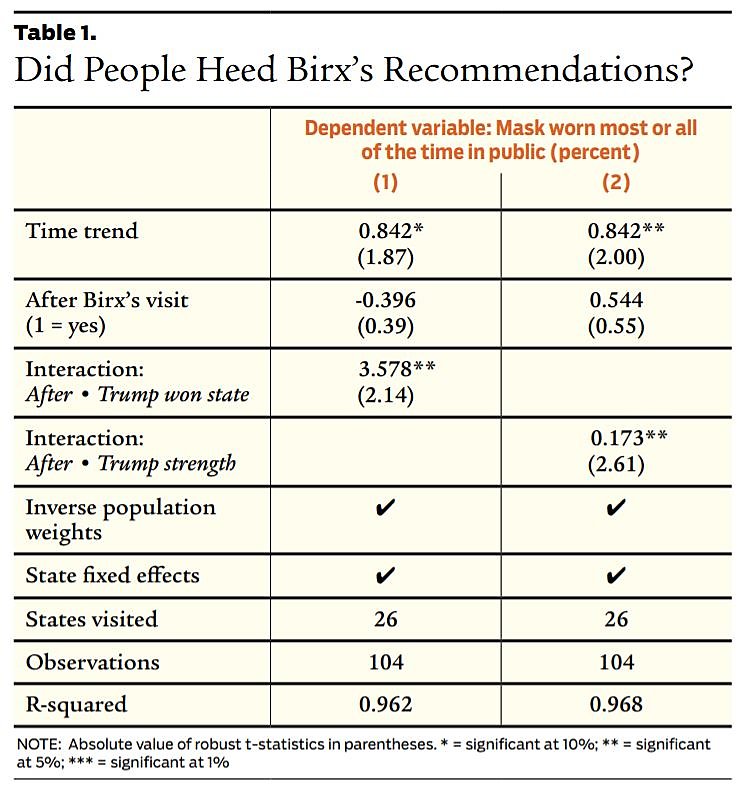

Let’s return to the question of whether Birx’s visits promoted mask-wearing. The mask-wearing survey of Facebook users is conducted daily. That allows me to construct variables for the percentage of state residents wearing masks both three weeks before and one week after her visits. In Table 1, the dummy variable After equals 1 for the week after a visit and 0 for each of the three weeks before a visit. Data are available for the last 26 of her visits. The regressions presented in Table 1 are weighted by the inverse of population to account for the greater difficulty of her being heard in larger states.

The regressions imply that people on average heeded Birx’s pleas to mask-up, but only in Trump-leaning states. Look at column (1). When the dummy variable Trump won state (in 2020) equals 1, the estimated coefficient on After becomes 3.182 (–0.396 + 3.578). This suggests that her visits increased the percentage of people wearing masks by 3.2 percentage points on average in Trump-leaning states. Since 22.1% of people in these states said that they rarely wore their masks in public prior to her visit, this estimate implies that she convinced 14.5% of them to mask up, at least for the following week. In contrast, the estimated coefficient on After is statistically insignificant in the states Trump lost, implying that her pleas did not alter behavior there.

Why did her pleas to mask-up persuade people in Trump country, but only Trump country? Perhaps because she was one of their own — that is, someone who worked in the Trump White House. They’d listen to her, especially because she came calling, and once they heard her, some of them decided to follow her advice. At the same time, she was preaching to the choir in the other states: over 90% of the people in the states Trump lost said they wore their masks most or all of the time, giving her fewer people to persuade. It also may have helped that the media seemingly delivered her message more vigorously in Trump country; my sense is that they gave her visits more coverage in Trump-leaning states because her message was out-of-tune with Trump’s and many red-state governors’.

Statewide Mandates: One Size Fits All?

In mid-August, Birx visited Missouri where she met with Governor Parson and afterward held a joint press conference. She was wearing a medical mask; he wasn’t. The first reporter to ask her a question noted that the governor had not imposed a statewide mask mandate and then asked, “What is your message to the governor [as to] how we’ve been doing?” She talked about the importance of data and then said, “I want to reassure everyone from Missouri [that the governor and his staff] are on top of the data. They know where this virus is and where the virus isn’t and they know what they’re doing to stop the virus.” She noted that “less than half” of Missouri’s counties have “active community spread,” and then vaguely endorsed the idea that “one size doesn’t fit all” when it comes to mask mandates.

The same reporter then asked more pointedly, “Should Missouri have a mask mandate?” She said she talked to the governor about a mandate and told him that “it’s easier to have a statewide mask mandate,” but that they’re unnecessary “if you can get 100% of the [state’s] retailers to require masks.”

A month later, amidst a rise in Missouri COVID cases, she sent Parson a (private) White House report on his state’s outbreak that recommended he impose a statewide mask mandate. Other governors, including North Dakota’s Burgum, received similar reports offering the same advice.

On a visit to North Dakota in late October, Birx and Burgum stood together to take questions from reporters. They were both wearing masks: hers was pink and his was black with “Dakota” written in white. The second question asked about whether the governor should issue a statewide mask mandate. Birx did not equivocate this time: “There is not only evidence that masks work, there is evidence that masks utilized as a public health mitigation effort work.” Asked to respond, Burgum said he completely agreed that masks work, but getting more people to wear them requires that the people appreciate why they should do so. He believed that a mask mandate was practically unenforceable and therefore wouldn’t do that.

Can Unenforceable Mandates Really Work?

Two days later, as Birx visited Wyoming, she seemed to be thinking about what Burgum had said. Most of the questions that day concerned whether Wyoming should impose a mask mandate. One reporter asked why mandates would be more effective than simply recommending people wear masks. Birx responded that mask mandates empower retail establishments to insist that their customers wear masks: it puts oomph into “No mask, no entry” signs, or perhaps gives retailers the courage to post them. She added, “It’s not that you need government enforcement, it’s that we need constant reminders when we are out in public to wear our masks.”

Mask mandates may empower women as well as retailers. Remember what Birx said about Alabama: more women than men were wearing masks there. My personal observation is that’s the case in Ohio as well. I’m 67 and have been careful not to expose myself to the COVID virus. Last October I went to my local Walmart to purchase 2‑cycle oil. Governor DeWine had imposed a statewide mask mandate a couple of months earlier, so I hoped everyone would be masked. When I arrived at the motor-oil aisle, a young couple was horsing around right in front of the 2‑cycle oil; the woman was wearing her mask, the man had his pulled under his chin. I stopped. She looked at me, turned to him and snapped, “Pull up your mask.”

Mask mandates may tip the solution of some battle-of-the-sexes games. The usual setup of this type of game is that you have a couple with different preferences for what to do on Sunday afternoon. The man wants to go to a Phillies game and the woman wants to visit the Philadelphia Museum of Art. But mostly they want to be together. There are two solutions, one where they both have a chance to catch a foul ball and the other where they both walk up steps made famous by Rocky. In our case, you just need to change the setup slightly. The two have different preferences over whether to wear a mask, but mostly they want to get along by choosing the same thing.

Greasing the Wheels in Four States

Birx was discreet about her recommendations to governors in their private meetings. Still, you don’t have to be Sherlock Holmes to infer that she recommended that they impose statewide mask mandates when their COVID outbreaks were widespread, severe, and/or spreading rapidly. As we’ll see, one governor outright acknowledged that she did. Also in her reports and public statements, she characterized mask mandates as one of several “best practices” for states with rapidly rising numbers of COVID-19 cases.

But did her visits and meetings nudge any governors to impose mask mandates or to postpone ending them? It’s tough to tell, and many of the analytical tools that economists use won’t help. There are, however, hints in newspaper articles, local television news shows, press conferences, press releases, and Twitter accounts.

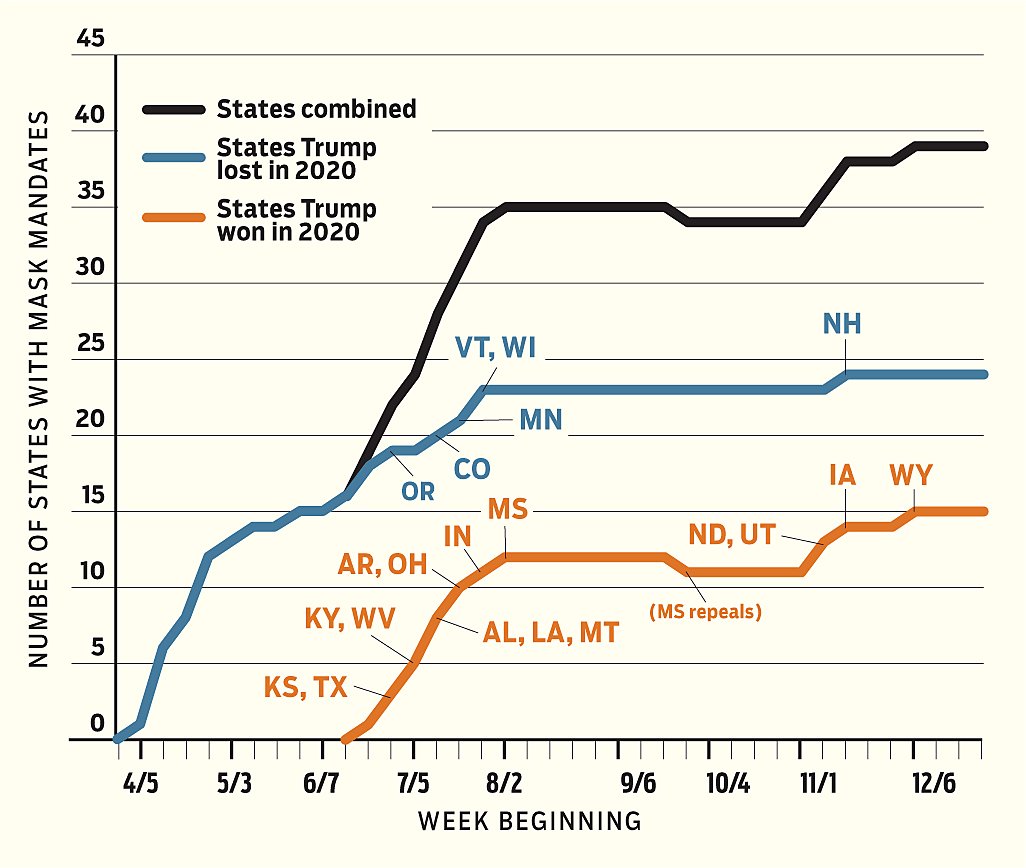

There are 21 candidates to consider: governors who imposed mask mandates sometime during Birx’s road trip. Figure 2 illustrates the total number of states with mask mandates in 2020, separated by whether President Trump won or lost the state in the 2020 election. By the end of the year, 39 states (and the District of Columbia) had imposed statewide mask mandates and only Mississippi had imposed and then repealed one (though several others, such as Alabama and Louisiana, had considered repealing their mandates).

Figure 2

Timing of Statewide Mask Mandates, 2020

The states whose abbreviations appear in Figure 2 are our 21 candidates. Below are four states where the evidence is particularly strong that Birx helped to persuade policymakers to either adopt mask mandates or maintain mandates that the states were poised to end.

Alabama / Gov. Kay Ivey wrapped herself as tightly to Birx as any governor in the country. Ivey announced the statewide mask mandate on the day of Birx’s visit and included pictures of the two of them on her Twitter account. She said that while the mandate would be difficult to enforce and was inferior to personal responsibility, the “numbers and data” Birx presented were “definitely trending in the wrong direction.” Something had to be done. When Mississippi repealed its mask mandate on Sept. 30 (a week after Birx’s third visit to Alabama), Ivey tweeted: “Dr. Birx told [me] that there’s no telling how many Alabamans have been saved because of this mask mandate. So, to those who want to see the mask orders go away, I’m asking you to please be patient a little while longer.”

Several characteristics suggest Birx played an important role in Ivey’s decision to maintain the mandate: The timing fits; indeed, Birx hustled back to Alabama after Mississippi repealed its mask mandate. There is evidence of a strong personal relationship between Birx and the governor. And the governor initially was reluctant to impose a mask mandate.

Kentucky / Gov. Andy Beshear wins the prize for the best quote about the importance of Birx in providing political cover for a Democratic governor in a Trump-leaning state: “She stood in front of our press and made it very clear that she and the administration supported the steps that we were going to take.” The fact that he was defending her after Nancy Pelosi said, “Deborah Birx is the worst,” and President Trump called her “pathetic” speaks to the strength of the personal relationship between Birx and Beshear.

Louisiana / According to the Washington Post, Gov. John Bel Edwards “initially resisted a statewide mask order, preferring to call for individual responsibility.” On July 11 he changed course and imposed a statewide mask mandate that was to expire two weeks later. At a hastily called press conference he said:

I do want everybody to understand that we’ve been extremely patient, but we’re making these decisions today because of the data that we have [about COVID cases in Louisiana]. We are also following White House guidance [that] governments consider face mask mandates where cases and positivity are increasing, and certainly that is the case here in Louisiana.

A few days later, he said that Birx “singled out [his] actions” for praise. Later in the fall, his supporters ran television ads featuring clips of her praising his mask mandate. Like Alabama, there are a lot of characteristics that suggest she helped to persuade Edwards to adopt the mandate.

North Dakota / Governor Burgum appreciates data. You can see that in the bones of his career: Stanford MBA, McKinsey consultant, entrepreneur, and senior Microsoft executive. He and Birx are alike that way, and that was reflected in his fulsome introduction of her at an October press conference, where his admiration of her “data-driven team” oozed from every pore. You can also see it in her demeanor: she’s happiest when talking about scientific studies.

A Fargo Forum headline claimed that Burgum and Birx had “clashed” over mask mandates. She was asked the next day whether that was true. With her voice bristling, she said, “Not only did I not clash with your governor, I have tremendous respect for your governor.” Then she spent several minutes enumerating ways in which he was “ahead of the curve” in protecting North Dakotans. The two respect one another.

Three weeks after her visit and 10 days after being reelected governor, Burgum surprised Dakotans by imposing a mask mandate and several other policies aimed at combating the COVID pandemic. In his address that night, he began by saying that North Dakota was “caught in the middle of a skyrocketing national COVID storm.” Then came a stream of data that could have easily come from Birx’s briefing books. It was a good speech: empathetic toward those who had suffered the loss of loved ones and emphatic about the need to stem the surge in COVID cases, especially to relieve the pressure on hospital capacity.

Birx deserves credit — or blame, depending on your perspective — for greasing the wheels of the governors’ move toward implementing mask mandates in these four states and making it harder to reverse course. But did the mandates save lives and, if so, how many?

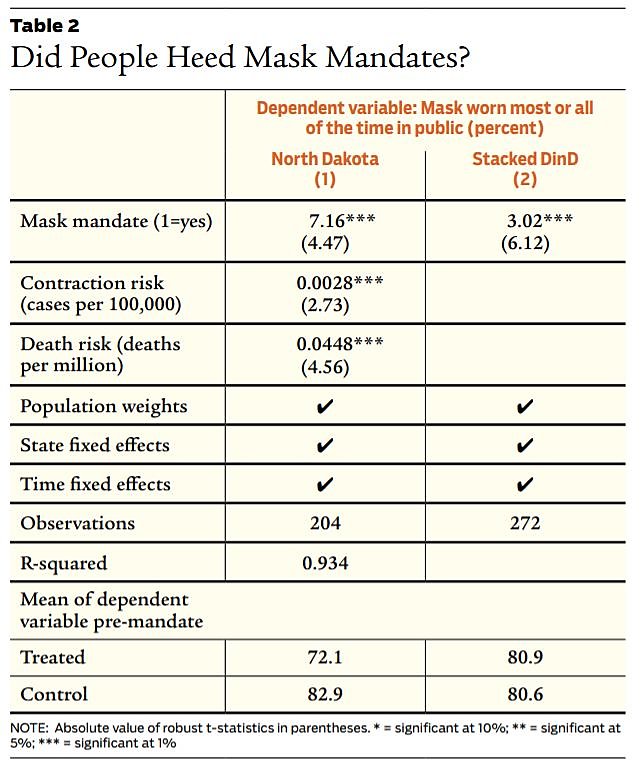

Do People Heed Mask Mandates?

The only way that mask mandates can save lives is if they induce people to wear their masks more often in public. Look back at Figure 1, which compares the mask-wearing behavior of Dakotans who responded to the Facebook survey. Not surprisingly, the percentage of Dakotans wearing masks increased during the fall surge in COVID cases and deaths. But only North Dakotans were required to wear them and, even for them, only after November 14. Look at the vertical gap in the percentage of people wearing masks between North and South Dakotans. The gap is wider after the mandate than before, suggesting that the mandate induced North Dakotans to mask-up relative to their neighbors to the south. But the difference is not statistically significant.

There are two things we can do to give our analysis a bit more oomph. First, we can compare North Dakota to the 11 (mostly) Trump-leaning states that didn’t impose mask mandates in 2020: Alaska, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Tennessee. The first column of Table 2 presents the regression that explains the percentage of people wearing masks in these states by the risks they face and a dummy variable for whether the state has a mask mandate. Because North Dakota was the only one with a mask mandate, the regression implies that the mask mandate increased the percentage of North Dakotans wearing masks by 7.16 percentage points relative to the other states. Prior to the mandate, only 72.1% of North Dakotans wore masks most of the time, compared to 82.9% in the other 11 states. Hence, the mask mandate gave retailors and the partners of mask-loathing North Dakotans just enough arm-twisting power to raise the percentage of North Dakotans wearing masks relative to the Trump-leaning states of the comparison group.

Don’t be fooled by the tiny coefficients on the risks of catching and dying of COVID. During the last week of September, 362 new cases of COVID-19 were diagnosed in North Dakota for every 100,000 people in the state. By early November, that number had increased to 1,219 cases per 100,000. In other words, the risk of catching COVID-19 had more than tripled. Similarly, the risk of death increased from 58 deaths per million to 137 deaths per million. Multiplying those changes by their tiny coefficients and summing them together, you get 6.4 percentage points. Hence, hearing stories about increasing numbers of their neighbors falling ill and dying of COVID over the six weeks from late September to early November induced a roughly 6.4 percentage point increase in the number of North Dakotans wearing masks.

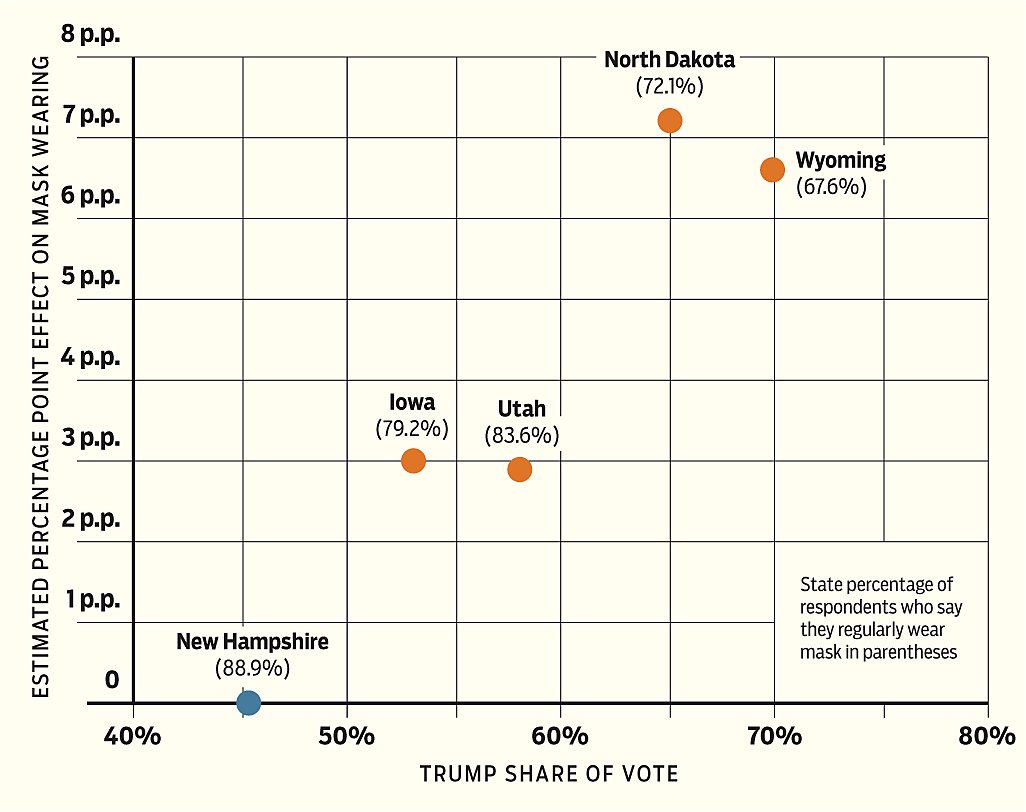

The second way to add some oomph to the analysis is to increase the number of states that imposed mask mandates during the time of the Facebook survey. Look again at Figure 2. Iowa, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming imposed mask mandates after the Facebook survey began asking about masking-wearing behavior. The second column of Table 2 presents the average of the estimated coefficients on the mask mandate variable from the five regressions where each state that imposed a mask mandate is compared with the 11 states that never did. The average effect of imposing a mask mandate in these five states is 3.02 percentage points, which is roughly half that of North Dakota (7.16 percentage points).

That made me wonder, is the arm-twisting potential of mask mandates greater in states where there are more arms to twist? In other words, do you get greater bang for your (political) buck in states where more people loath wearing masks?

Figure 3

“Bang for Your (Political) Buck” via Mask Mandates

Figure 3 plots the estimated effect of mask mandates against the percentage of the state’s population that voted for President Trump in the 2020 election. The numbers within parentheses are the percentage of people who almost always wore masks prior to the mask mandate. President Trump was rarely seen wearing a mask; indeed, the first time he was photographed wearing one was so newsworthy that it led the NBC and ABC evening news. Many of his supporters were equally reluctant to wear masks, as can be seen by the lower percentage of people who wore masks in the two states — North Dakota and Wyoming — with the highest number of Trump supporters. Mask mandates principally work by empowering retailers, friends, and partners to twist the arms of unmasked people to mask-up. The greater number of Trump supporters in states like North Dakota and Wyoming means there are more arms to twist there and, as a result, it’s not surprising that the estimated effects of mask mandates increase with the size of Trump’s vote in the 2020 election.

Lives Saved

President Trump swept the four states discussed above — Alabama, Kentucky, Louisiana, and North Dakota — with, on average, 62% of the vote in the 2020 election.

In a Twitter thread that began with Governor Ivey announcing that she was extending Alabama’s mask mandate, she quoted Birx as saying, “There’s no telling how many Alabamans have been saved because of this mask mandate.” Sure, it’s impossible to know with certainty, but we can estimate the number of lives saved by the mandates in each of the four states.

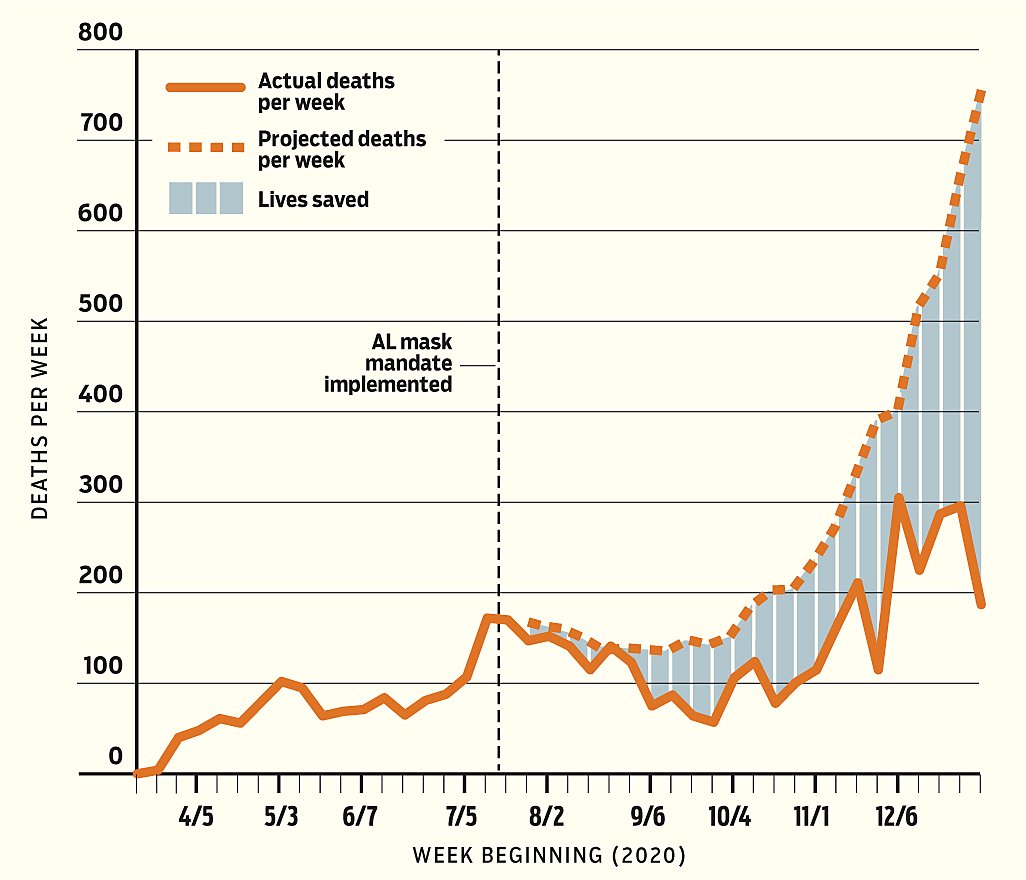

Several teams of economists have estimated the effect of statewide mask mandates on COVID cases and deaths using sophisticated econometric models. My favorite in terms of readability and relevance is “The Roles of Mobility and Masks in the Spread of COVID-19,” written by four economists at the Boston Federal Reserve. I replicated their data and estimated a similar (but deliberately simpler) specification. My regression explains the weekly growth rates of COVID deaths using its lagged values and lagged variables for whether the state had a mask mandate and for the percentage of the state’s population that sheltered in place. I also included state fixed effects and epidemic time effects (described in the paper cited above) and weighted the regression by the state’s population.

My best guess is that Ivey’s decision to impose a mask mandate saved 2,892 lives in Alabama over the last six months of 2020. Figure 4 illustrates how I came up with that number. First, I regressed the weekly growth rate of COVID deaths on the explanatory variables for all 50 states using weekly data spanning the second full week in February of 2020 to the last week in December. Second, I created the predicted values of the weekly growth rates for Alabama using all of its values of the explanatory variables except for the mask mandate variable. This last variable was switched from 1 to 0 for the weeks after the mask mandate was imposed so that the predictions give us an idea of what would have happened had there been no mask mandate.

Figure 4 illustrates how the predicted path of COVID deaths without a mask mandate would have deviated from the actual number of deaths per week in Alabama. Vertical lines indicate the predicted number of lives saved each week after the imposition of the mask mandate. The first vertical line, which is 22 lives long, appears two weeks after the mask mandate because the model assumes COVID infections prevented by mask mandates wouldn’t have immediately led to deaths; it takes about two weeks after contraction of the virus for someone to die. The sum of the lines yields my prediction that 2,892 additional lives would have been lost had the mask mandate not been imposed.

The mask mandate is the only policy that appears as an explanatory variable in my regression, so its estimated coefficient reflects the effect of other policies that are likely to be correlated with mask mandates. I’m sure a lot of governors were like North Dakota’s Burgum, who packaged his mask mandate with other policies aimed at “bending the curve” in COVID cases and deaths. If you wanted to know the pure (or partial) effect of mask mandates, you would want to control for those other policies. But Birx’s advice to governors was aimed at bending the curve, so using mask mandates as a proxy for her advice is, I think, appropriate.

My best guess is that the mask mandates in Alabama, Kentucky, Louisiana, and North Dakota saved roughly 12,000 lives in the remaining months of 2020 after they were introduced.

What about lives lost? / I could also choose to say that governor so-and-so lost such-and-such number of lives by not heeding Birx’s advice to impose a statewide mask mandate. The mechanics of doing this are easy: just reverse the exercise described above. But saying someone cost people their lives is more explosive than saying someone saved people’s lives. Suppose I’m wrong about my estimate of the effect of mask mandates — that I’ve inferred that they’re effective when they’re actually not.

Don’t get me wrong. I believe that mask mandates result in fewer deaths, both because of studies upon which this article’s modeling is based and because of other evidence like what Birx cited. But I think it’s appropriate to set a higher threshold for the strength of the evidence necessary to talk about the number of lives lost by a policy decision than the number of lives saved. Birx implicitly agrees with this; she lavishly praised governors who imposed mask mandates but refrained from publicly criticizing those who didn’t. I doubt that she ever told any of the 11 governors who didn’t impose a mask mandate that there was “no telling how many” of their citizens have been lost because they didn’t do so.

Figure 4

Projecting Alabama’s COVID Deaths Without Mask Mandate

All 11 of those governors were Republicans. The Republican governors who did institute mask mandates always talked about how reluctant they were to do so. The tipping points for many of them were spikes in hospitalizations that were leaving few beds or doctors to care for anybody else. The positive externalities of wearing masks became too large to ignore, making the argument that the choice ought to be left to individuals increasingly untenable.

The idea that all you need to do is give people information about COVID and trust them to make the best choices for themselves wasn’t enough even when the hospitals weren’t near to overflowing. Given the acute shortage of high-grade “N95” masks, the only surefire way to protect yourself from unmasked individuals was to become a hermit. Perhaps the so-call Swedish model for fighting COVID would have worked better if N95 masks were in plentiful supply: people likely to get severe cases would rationally choose to wear N95 masks and everyone else would willingly embrace the external costs of their unmasked brethren to the alternative of wearing a mask most of the time.

The two Dakotas are governed by leaders who strongly lean libertarian. They genuinely want people (and the firms they lead) to be able to make their own choices unencumbered by the heavy hand of government. Yet only one of them — North Dakota’s Burgum — imposed a statewide mask mandate. One might argue that that makes him a poster boy for the pithy slogan that “there are no libertarians in a pandemic,” but I don’t agree. I believe that a libertarian is perfectly justified in imposing a mask mandate to mitigate the pervasive and life-threatening negative externalities imposed on bystanders by COVID. I also doubt that mask mandates infringe on protected liberties any more than many other beneficial health regulations that libertarians take for granted. The best discussion of these issues that I’ve found is the Cato paper “Government in a Pandemic.”

Lessons Learned

We know quite a bit about the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions — e.g., mask mandates, school closures, prohibitions of mass gatherings — during this and earlier pandemics. One of the best and earliest studies of these interventions is a 2007 JAMA article by Howard Markel et al. that found that school closures, cancellation of public gatherings, and contact-tracing during the 1918 influenza pandemic flattened the mortality curves in cities that implemented them and reduced the total number of deaths.

We currently know much less about the effectiveness of campaigns to persuade people and policymakers to change their behaviors and policies during the COVID pandemic. Birx’s efforts represent a unique opportunity to test whether they work.

More than anything else, she urged reluctant people to mask-up. On her months of travel, she visited nearly every state on the continent and had meetings with most of their governors. And she was careful to tailor her message to each state. When she visited Kentucky, she presented data about Kentucky to explain why it was important for Kentuckians to wear masks. She did the same when she visited Massachusetts. But the evidence suggests that people were more likely to change their behavior in states like Kentucky than those like Massachusetts.

She was officially, if not actually, one of President Trump’s top advisers on the COVID-19 epidemic. That was important to the people listening to her because she carried the authority — and baggage — of the Trump White House. The authority helped her reach people in Trump-leaning states and convince a good number of them to mask-up. The baggage made it easy for people elsewhere to ignore her.

This was generally true of governors as well. Birx had the greatest influence on — or at least presence among — governors of Trump-leaning states, especially those who were on the fence about whether to adopt mask mandates. She nudged a small number of governors toward the mandate side of the fence by presenting persuasive data, being respectful of their policy positions, and providing them with political coverage.

The effectiveness of her campaign depended on her credibility. She was credible to many because of her training and experience; she knew her facts and could speak authoritatively and understandably about the ways people can protect themselves (and governors can protect their constituents) from the virus. Governors, reporters, and ordinary citizens were also impressed that she came in person to deliver her warnings, traveling for hours alongside tracker-trailers, RVs, and state cops — a life that resembled Willy Loman’s more than Steve Mnuchin’s. And, of course, she had credibility among Trump supporters because she came from the Trump White House: she may not have worn MAGA scarfs, but — at least officially — she was one of his people.

Birx’s credibility took a hit in mid-December when the Associated Press reported that she had traveled to Delaware on the day after Thanksgiving and she and her husband had at least one family meal with her daughter, son-in-law, and two young grandchildren. She did what she said people in Utah (and elsewhere) shouldn’t do: get together with extended families for Thanksgiving. As understandable as her desire to be with family on a major holiday was, it is important to practice what one so prominently preaches.

Still, you’ve got to respect her willingness to go on the road for months during a global pandemic. The evidence suggests that her road trip induced thousands of people to mask-up and helped nudge a few governors to impose mask mandates — decisions that saved thousands of lives. Few of her critics would have been willing to do it.

We could use a similar “sales job” today. Thanks to some amazing innovation, the country is now armed with millions of doses of vaccines that are highly effective at suppressing illness and death from COVID. But the same sort of hesitancy about masks is plaguing efforts to vaccinate Americans. In states Trump won, government estimates indicate that 21% of people are hesitant to be vaccinated, compared to 13.5% in the rest of the country. That is reflected in actual vaccination rates; as this article goes to press, 4.4 percentage points fewer people are vaccinated in states Trump won.

Birx-like persuasion might reduce this gap in people’s willingness to be vaccinated, moving the country closer to herd immunity. According to my estimates, Birx nudged 14.5% of those reluctant to wear masks to do so. If someone like her was just as successful in nudging people to get vaccinated, the hesitancy rate in states Trump won would decrease from 21% to 18%. That would close 40% of the hesitancy gap between states Trump won and lost and, as a result, help close the vaccination gap between them.

Partisan divides in this country run deep, but Americans respond when called to action — especially when those calls are tailored to their experiences and spoken in their communities. Birx’s efforts showed the power of such personal calls to influence public health behaviors. I now hope someone like her can encourage all Americans to receive a life-saving vaccination regardless of their politics.

Readings

- “Government in a Pandemic,” by Thomas A. Firey. Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 902, November 17, 2020.

- “Nonpharmaceutical Interventions Implemented by US Cities during the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic,” by Howard Markel, Harvey B. Lipman, J. Alexander Navarro, et al. JAMA 298(6): 644–654 (2007).

- “The Contagion Externality of a Superspreading Event: The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally and COVID-19,” by Dhaval Davel, Drew McNichols and Joseph J. Sabia. Southern Economic Journal 87(3): 769–807 (2020).

- “The Roles of Mobility and Masks in the Spread of COVID-19,” by Daniel Cooper, Vaishali Garga, María José Luengo-Prado, and Jenny Tang. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Research Paper Series Current Policy Perspectives Paper No. 89224, December 2020.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.