What Trump definitely can be evaluated on is whether he contributed to America being better prepared for a shock and how the country was faring in the years before 2020. This article looks at the administration’s economic performance from this perspective. The more solid the economy, the better prepared individuals are to face a public health and economic shock.

During the first three years of Trump’s presidency, the economy expanded, unemployment and poverty fell, wages increased, taxes were cut, the stock market moved upward, and some reforms of federal regulation were introduced. So far so good.

Yet we need to be careful before offering kudos to the president. His is a powerful office, but his control over the economy is limited. His administration is constrained by the Constitution and the other branches of government. The policies of previous presidents and Congresses helped establish economic trends. The Federal Reserve System has the power to create money, but this does not give it unlimited power over the economy. Finally, the U.S. economy is only 15% of the world economy and the remaining 85%—which the president cannot easily order around—exerts, through trade, a major influence on domestic prosperity.

The “Trump economy” is thus a misnomer. Like any other president, Donald Trump is only partly responsible for what has gone well and gone wrong during his years in office and in the years to come. A president can do more damage to an economy than help it. And three years is a short time to evaluate the consequences of complex policy packages. All these caveats must be kept in mind.

Moreover, judging how an economy is performing—leaving alone the question of who is responsible for that performance—is more difficult than it might seem. The ultimate criterion should be the welfare of all individuals. But welfare is subjective and impossible to measure directly, let alone comparing it between individuals, so real income (measured by gross domestic product) usually is the substitute criterion. In economic punditry and even academia, other metrics are also used, such as employment, investment, and wages.

It is helpful to compare Trump’s first three years to the performance of his immediate predecessor, Barack Obama. The two have much in common: both turned out to be interventionists and many classical liberal or libertarian economists would argue they both did more economic harm than good. Comparing them helps to provide economic and historical context.

Employment

Employment and unemployment measures are indicators, but only indicators, of economic flexibility and prosperity. Employment is not the goal of life; we work to consume, not the other way around. For a given level of income, people would generally prefer to work less. Over time and except in periods of macroeconomic shocks such as recessions, the level of employment closely follows the level of working-age population. Labor may be more or less productive, of course, which implies that jobs will pay more or less, but unless public policies cause recessions, incentivize people not to work, or stifle development, their effect on unemployment is limited.

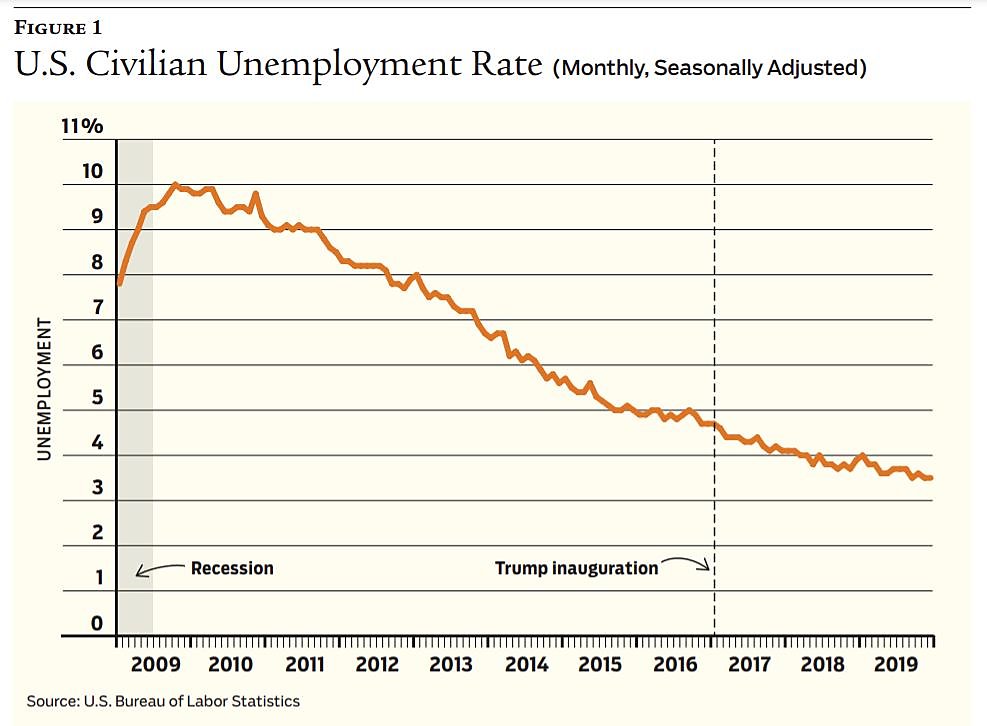

With these qualifications in mind, let’s see what happened to the unemployment rate over the Obama and Trump presidencies. Figure 1 shows that it reached 10% in October 2009, four months after the end of the Great Recession. Obviously, that recession was not Obama’s fault, although he arguably could have accelerated the recovery by being less interventionist. Still, unemployment decreased steadily during his presidency, reaching 4.7% in December 2016. Under Trump it fell to 3.5% three years later, the lowest since 1969. (Of course, things have changed dramatically since then.) Though unemployment reached its lowest level under Trump, it fell faster and further under Obama. But not much can be made of that; the decline likely slowed under Trump because there wasn’t much further unemployment could go.

Trump’s first three years can be credited with improvement in the labor force participation rate (the proportion of prime-working-age individuals who are either employed or looking for a job), which increased from a low of 62.4% in 2015 to 63.2% in December 2019. That may seem small, but it indicates an active labor market where discouraged individuals who previously were not looking for work reentered the workforce. By itself, the increase in the labor force (the denominator of the unemployment rate) exerted downward pressure on the unemployment rate, which, one might think, should have gone down faster. However, a slowing in the decrease of the unemployment rate is to be expected as the economy draws closer and closer to full employment.

The Trump administration likes to stress that African Americans and Hispanics have especially benefited from the decline in unemployment. That is true, but they similarly benefited during Obama’s second term.

The poverty rate decreased under the Trump administration, but at a slower rate than in the last two years of the Obama administration. (The last year for which data are available is 2018, so we only have two years of data for the Trump administration.)

Overall, the poverty and unemployment picture improved slowly from 2009 to 2019, with no radical break when the occupant of the White House changed. The Obama economy and the Trump economy seem to be the same economy. This observation applies to many other measures of American prosperity.

Economic Growth

Along with employment, the Trump administration likes to trumpet its record on economic growth. Here too, Trump’s record is not much different than Obama’s.

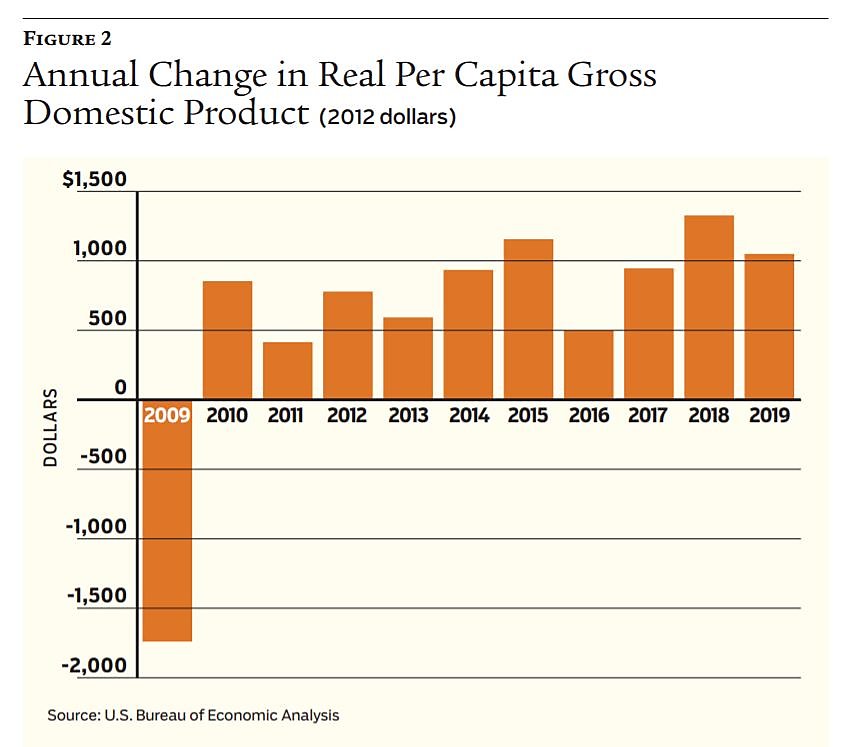

Figure 2 shows the annual growth of real GDP per capita. Obama inherited the Great Recession, which had started nearly a year before his election and had its worst quarter in late 2008. Obama could not avoid the recession any more than Trump could avoid the pandemic.

The recession ended two quarters into Obama’s presidency. The chart suggests that the annual growth of real GDP per capita has been better under Trump, even if we ignore the 2009 negative growth. Under Obama, the average annual growth starting in 2010 was 1.4%. Under Trump, it averaged 2.0%, though the upward trend slowed in 2019, falling to 1.8%, which is roughly the same level as 2017. These data are consistent with the continuation of a slow recovery from the Great Recession.

Compare economic growth during the Trump years with what his Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) forecasted in its Annual Report in February 2018. The CEA predicted total (not per capita) real GDP growth of 3.1% in 2018 and 3.2% in 2019, followed by cruising speed of about 3.0% per year, presented as the “return to historical rates of economic growth” promoted by the Trump agenda. The actual growth rates were 2.9% in 2018 and 2.3% in 2019, quite below the forecasts and not much different than under the Obama administration.

No one can be blamed for badly predicting the future (except if it is based on delusion). One can also argue that GDP growth over just a couple of years is not meaningful. So, we should consult some other indicators.

Before we do that, though, we can get another perspective by noting that under both Trump and Obama, the American economy generally grew faster than the Canadian and Eurozone economies. The gap with Canada was larger under Trump and the gap with the Eurozone was larger under Obama, which partly reflects the Eurozone’s stagnation in the first part of the 2010s and the Canadian slowdown in the second part. This comparison is not decisive, but it does not seem to represent the constant “winning” that Trump promised.

Stock market / Didn’t the booming stock market indicate something special with the Trump economy? In fact, the stock market was not much different, and was less volatile, under Obama.

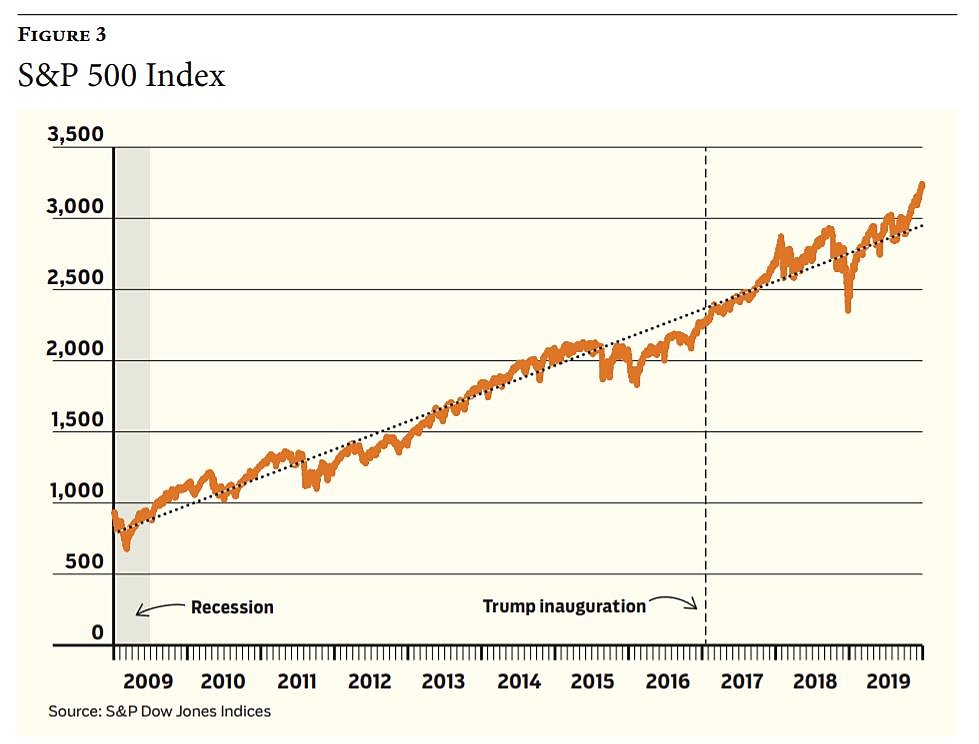

Figure 3 shows the daily value of the S&P 500, an index of the stock prices of the 500 largest listed U.S. companies. The linear trendline has a large r-squared of 0.9719 (a measure of the proportion of the changes explained by the trendline) and helps show both the relative continuity between the Obama and Trump years and the volatility under the latter. The average daily increase in the index is virtually indistinguishable under the two presidents (0.0500% under Obama, 0.0502% under Trump). The index increased on 54% of trading days under Obama and 56% under Trump.

It is true that the index boomed at the end of 2019, but no less true that it crashed at the end of 2018. The large drop in stock prices at the end of 2018 was partly due to fears over the administration’s trade war with China. From the beginning of October to December 24, 2018, the S&P 500 fell by nearly 20%, a decline unseen since the Great Recession.

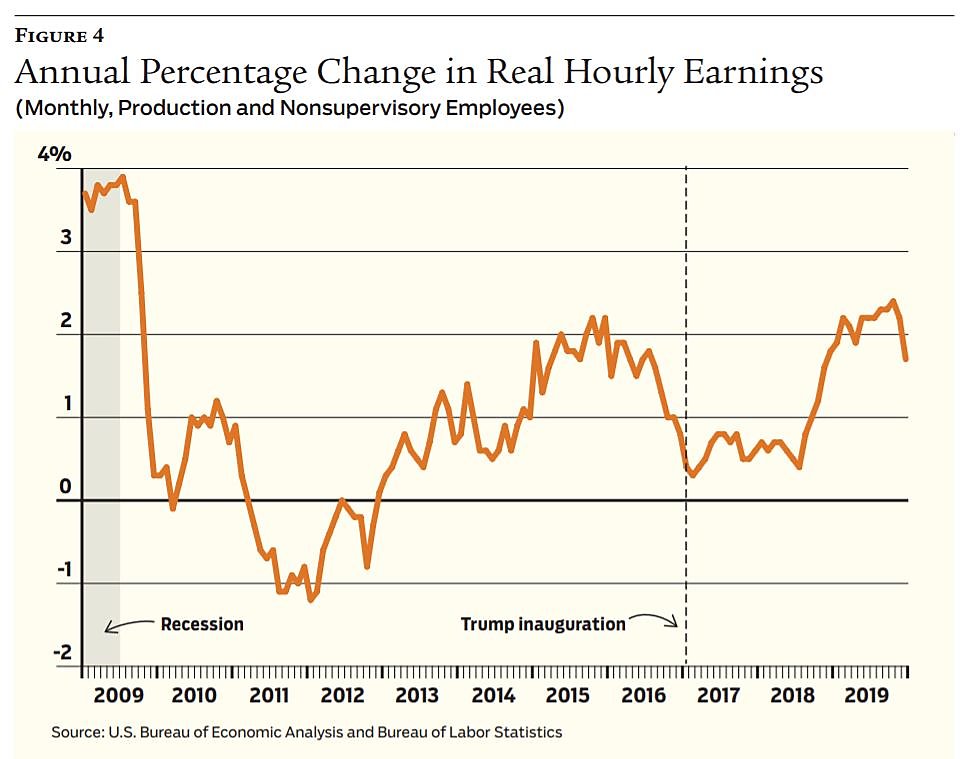

Wages / The CEA’s 2020 Annual Report stresses that the real wages of workers at the bottom of the income distribution have improved during the Trump presidency. According to the report, “The real wages of private sector production and nonsupervisory workers increased by 1.9 percent during the year ended in November 2019.” That improvement is seen in Figure 4. But note that the significant increases only started in mid-2018 and that all gains in 2019 were actually cancelled by the last two months of the year. Moreover, the average monthly rate of increase was only marginally better under Trump (1.2%) than during the Obama presidency (1.0%).

Again, the Trump economy appears to be a continuation of the Obama years. When Trump entered the Oval Office in the first quarter of 2017, the recovery from the Great Recession, although slow, was already one of the longest measured recoveries in American history. In the middle of Trump’s third year, the American expansion became the longest one: 10 years and six months. So, Trump must have done something right—or, at least, he did nothing so bad that it derailed what was already occurring.

Deregulation

Economic analysis suggests that regulation—and certainly regulation over and above what is economically justified—stifles economic growth. In a recent article, economists Bentley Coffey, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Pietro Peretto estimate that federal regulation reduced economic growth by 0.8% per year between 1980 and 2012. (See “A Slow-Motion Collapse,” Winter 2014–2015.)

President Trump and his supporters often lionize his administration’s deregulation efforts. There has indeed been some success, but it should be qualified.

Trump’s Executive Order 13771, signed January 30, 2017, mandated the elimination of two existing rules (or formal regulations) for any new one implemented. The latest edition of regulatory analyst Clyde Wayne Crews’s annual report Ten Thousand Commandments notes that this goal was more than achieved over the first three years of the Trump administration. However, Crews adds, last year showed a notable loss of momentum as there were more regulatory actions than deregulatory actions in the pipeline at the end of 2019.

Last year showed a notable loss of momentum as there were more regulatory actions than deregulatory actions in the pipeline. Moreover, the administration’s deregulatory results have proceeded through executive fiat, not legislation.

We can find many examples of the elimination or attenuation of previous regulations: so-called net neutrality, the health insurance mandate, constraints on health insurance policies, the Food and Drug Administration’s slow-motion approval of competitive drugs, the Obama administration’s expansion of the definition of “joint employer” to cover employees of franchisees, a small number of Dodd–Frank financial regulations (notably for community and regional banks), some rules on the identification and protection of endangered species, and certain regulations on energy and mining companies. Indirect regulation through regulators’ guidance documents was also restrained. (See “Regulatory Agencies Get Guidance on ‘Guidance,’ ” Spring 2020.)

Still, President Trump’s deregulatory achievements are limited. Giant frameworks of federal regulation are largely unchanged. For example, the structure of the Dodd–Frank Act, with its multitudinous regulations, remains intact. Further, as Crews notes, the administration’s deregulatory results have proceeded through executive fiat, not legislation, and any future president can easily reverse them.

Moreover, the administration simultaneously pushed new regulations. Hospitals will now have to publish their prices. The Securities and Exchange Commission has deemed digital currencies to be “securities.” The administration has greatly increased restrictions on American importers and, thus, on American consumers and businesses that use imported goods. Trump and his administration also indicated their intention or desire to regulate family leave, cryptography, artificial intelligence, and social media, as well as to tighten antitrust regulations and controls. The president and some of his close associates often speak as if they want industrial policy: government coordination and orientation of industrial and commercial development.

How much regulation? / Measuring regulation is notoriously difficult. For example, is a new rule more burdensome than the one or two that were abolished?

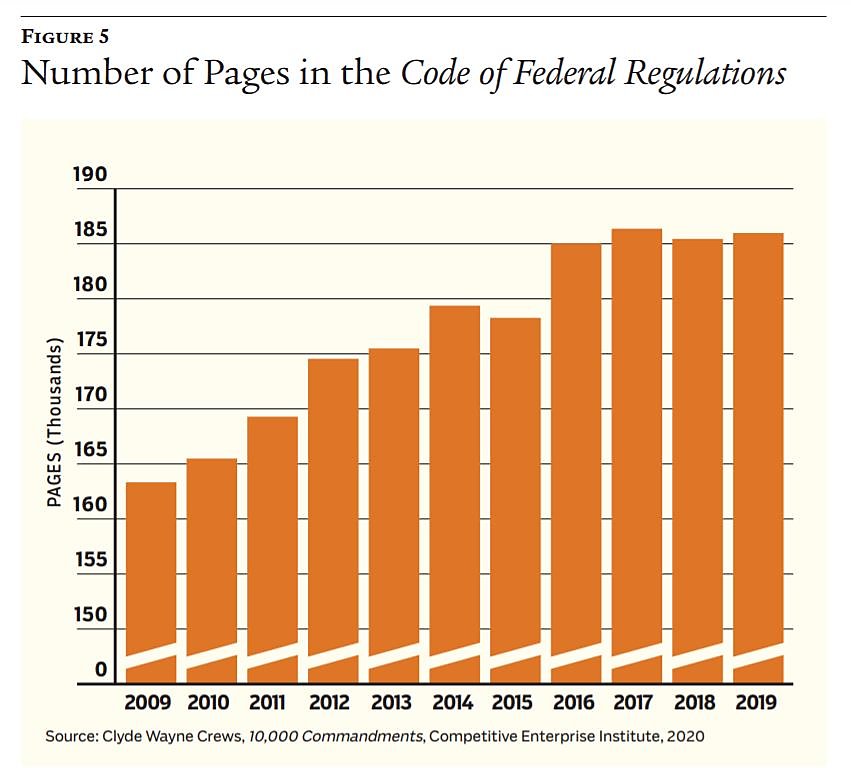

Crews observes that “calendar year 2019 ended with 2,964 final rules in the Federal Register [the daily repository of new regulations proposed or enacted by the federal government], which was the lowest count since records began being kept in the 1970s.” Another way to measure regulation is to count the number of standard pages in the Federal Register. The average number of pages per year has been 66,490 under Trump, compared to 80,421 under Obama. On these measures, Trump presided over a rare slowdown in the increase of new regulations. But a slower increase is still an increase.

A new regulation typically is necessary to abolish or modify an existing one. Consequently, the Federal Register does not provide a measure of the net increase in regulations. A better measure is the number of pages in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) which, every year, codifies all federal regulations existing at that point in time. (In reality, the CFR’s different sections are codified in a staggered way over the year, introducing some noise in annual comparisons.)

Figure 5, which gives the number of pages in the CFR over time, suggests that the Trump administration has roughly capped the total volume of federal regulations at, or slightly over, the 185,000 pages they comprised at the end of the Obama presidency. According to this measure, the Trump administration stopped the growth of regulation, but it did not deregulate. Ryan Young, a senior fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute and colleague of Crews, summarizes the situation:

President Trump’s first three years of regulation are mixed. He deregulated in some areas and added new burdens in others. Transparency problems and poor data quality from agencies make it impossible to tell for certain if Trump has been a net deregulator. The most likely verdict is that he has slowed regulatory growth but has not cut regulation on net.

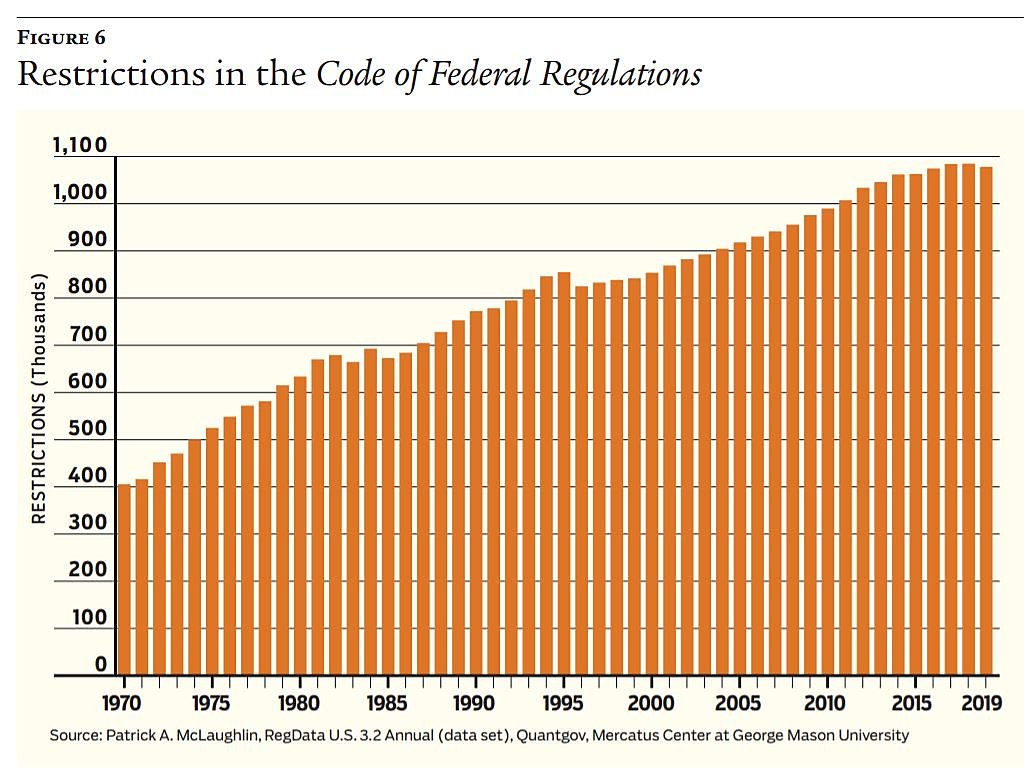

Figure 6, measuring “restrictions” (as determined by the use of words such as “shall,” “must,” and “prohibited”) in federal regulation, offers a somewhat more favorable view of the Trump administration’s deregulatory effort. At the same time, the longer trend it depicts dampens optimism for the future. After totaling a bit more than 1 million in 2016, the number of restrictions barely grew in 2017, was essentially flat in 2018, and then decreased slightly (–0.6%) in 2019. Such decreases are rare: since 1970, that only occurred under presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, and then only briefly before resuming an upward trend.

Perhaps Trump’s deregulation instincts were clear, but they have not been accompanied by coherent ideas. On October 17, 2018, he declared of his deregulation agenda, “I think within a period of about another year, we will have just about everything we’ve wanted.” No wonder that, at the end of 2019, the future of deregulation was uncertain, even with no coronavirus in view.

Trade

One area of increased regulation under Trump has been foreign trade. He launched trade wars against not just Chinese products, but also goods made in allied countries, notably South Korea and Europe.

Tariffs are one means of foreign trade regulation. The Harmonized Tariff Schedule lists all tariffs on several thousand specific goods. Just after Trump took office, the version published in February 2017 had 3,707 pages; obviously, the United States was not a bastion of unfettered trade. By the end of 2019, he had added an additional 248 pages, bringing the total to 3,955 pages.

Payment of these tariffs is not the only encumbrance of Trump’s protectionism. The new tariffs on Chinese imports prompted more than 4,500 American companies to use scarce time resources and legal help to file 52,700 requests for exemptions, most of which were rejected. According to a compilation by the Wall Street Journal, 70% were refused in the first two waves of Trump’s tariffs and 97% in the third wave. Bureaucrats are now wading through requests from his fourth wave, announced last fall.

Crews notes:

Trump also issued a January 2019 executive order on “Strengthening Buy-American Preferences for Infrastructure Projects.” That was followed in summer 2019 by an order on “Maximizing Use of American-Made Goods, Products, and Materials” in federal contracting.

These are more burdens imposed on American companies. The administration also used existing protectionist regulation more intensely.

Trump’s trade wars increased prices for many American companies and American consumers. Just like any other restriction of economic freedom, these interventions constrained free exchanges in which Americans voluntary participate. They thus reduced economic efficiency and income in the United States.

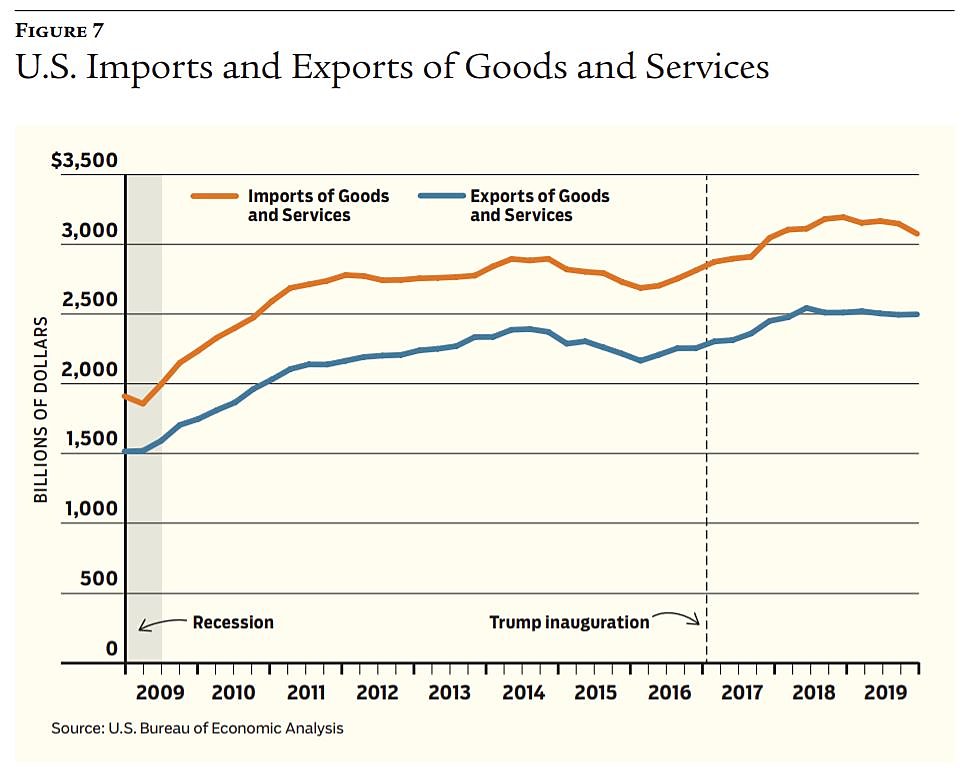

Figure 7 shows that, during Trump’s first three years, exports of American goods and services ceased growing, which they had been doing with little interruption since the end of the Great Recession. (In 2015, a deceleration of economic growth in both the United States and its main trading partners briefly reduced both exports and imports.) Under Trump, imports started decreasing at the beginning of 2019. Both imports and exports increased faster under Obama (1.3% per quarter in both cases) than under Trump (0.6% for imports and 0.8% for exports).

Explaining the slowdown of American growth in 2019, Trump’s CEA gives due weight to the adverse effect of slowing international trade. The CEA further emphasizes the “downside risk” of a continuing slowdown in trade, adding that slow economic growth in China “would also introduce substantial risks to the outlooks for advanced economies, including the United States.”

Two econometric studies cited by the CEA, notably one by Mary Amiti, Stephen Redding, and David Weinstein, estimate that Trump’s trade wars have reduced U.S. GDP by around 0.4% per year. The CEA does not admit that. It suggests the rather ludicrous idea that the Trump administration is engaged in the “pursuit of freer, fairer trade, with zero tariffs, zero nontariff barriers, and zero subsidies.” (See “Peter Navarro’s Conversion,” Fall 2018.)

Life changed drastically in early 2020. In the United States, that would have happened regardless of who was president; the White House can’t order viruses around, after all. And if someone other than Donald Trump had been president, the country likely still would have experienced government failures in testing for COVID-19, containing the epidemic, and maintaining free markets. Such failures are common in political and bureaucratic systems.

Federal Finances

Adopted on December 22, 2017, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced both corporate and individual federal taxes. By reducing the corporate income tax rate to 21% from a graduated structure culminating at 35% as well as by cutting other taxes, the TCJA has been praised for pushing down the cost of capital and increasing investment. In the second quarter on 2019, though, net domestic private business investment started slowing down and, by the end of the year, was close to the low of the second quarter of 2016. In the downward trend of late 2019, special factors like Boeing’s trouble with its 737 MAX airliner as well as reduced oil and gas drilling played a role. It is quite possible that business investment would have been even lower without the TCJA.

The TCJA probably increased the rate of GDP growth. According to an estimate by Anil Kumar of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, GDP growth in 2018 was 0.8 percentage points higher than it would have been without the TCJA’s tax cuts, which would thus account for more than a fourth of that year’s economic growth. We may add that, other things being equal, the growth effect should be greater in the longer run through increased investment and productivity. This is an important benefit—or it would be if the tax cuts had been accompanied by at least an equal cut in expenditures to freeze the federal deficit.

In the spring of 2016, then-candidate Trump told Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Robert Costa, “We’ve got to get rid of the $19 trillion in debt,” referring to the gross federal debt (which actually was $18.1 trillion at the end of 2015). “How long would that take?” the interviewers asked. “Well,” Trump answered, “I would say over a period of eight years.” Would he increase taxes to achieve that? “I don’t think I’ll need to,” he replied. “The power is trade. Our deals are so bad.”

It’s unclear why he segued to trade. A charitable interpretation is that he confused the federal government’s budget deficit with the country’s trade deficit, which are two very different things. But assume that he was not confused; eliminating a federal debt of $18.1 trillion in eight years would have required, over each of those eight years, a reduction in expenditures of 61% or an increase in taxes (which make up nearly all federal revenues) of nearly 70%.

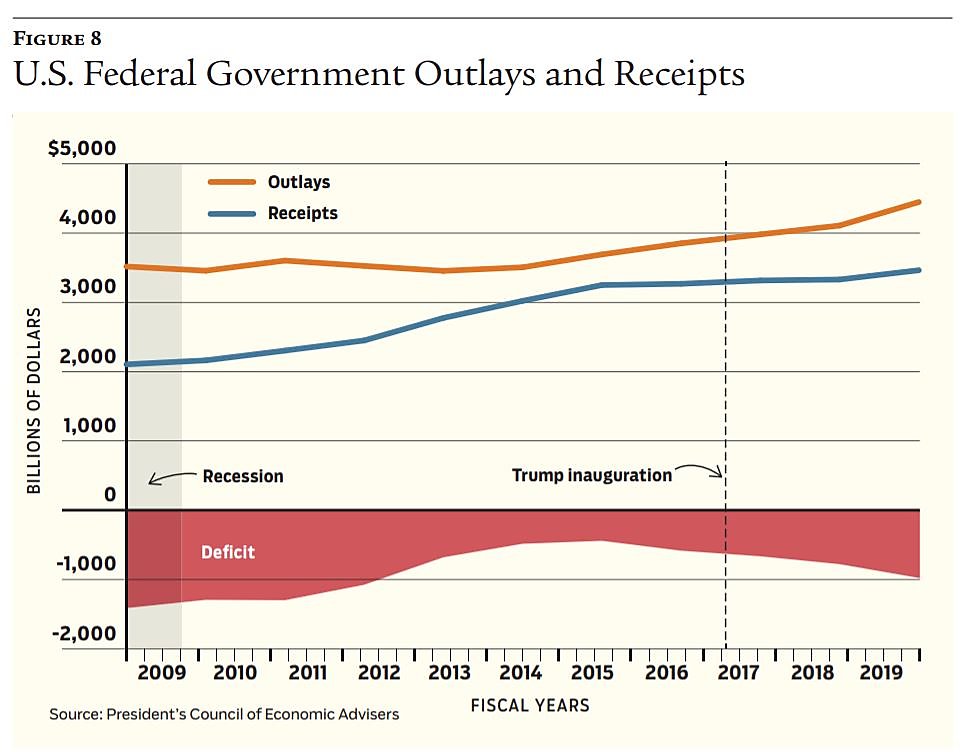

So, what did President Trump do about the annual deficit during his first three years in office? As Figure 8 shows, he oversaw an increase in the deficit from $585 billion in Obama’s last year to $984 billion in the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2019. (Fiscal years run from October 1 to September 30, so FY2019 ended on September 30, 2019.) The increase was due mainly to higher outlays. Receipts increased little despite continuing economic growth, probably because of the 2017 tax cuts. On December 31, 2019, the (gross) federal debt was up 14% from 2016 and reached $22.7 trillion. Now the federal government is borrowing trillions more in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

In budget matters, of course, the president needs the cooperation of Congress, which alone has the constitutional power to vote appropriations and taxes. Congress is at least as responsible as the president for the growth in the deficit. But recall that in 2017 and 2018 Trump had a Republican majority in both chambers.

There is little to suggest that, once in office, he was concerned about growing expenditures and deficits. On January 17, 2020, at a Republican fundraiser, he declared: “Who the hell cares about the budget? We’re going to have a country.” With a growing deficit on the upside of the business cycle, the federal government was badly prepared for any recession or other shock that could happen. And so here we are.

Planning and Disorder

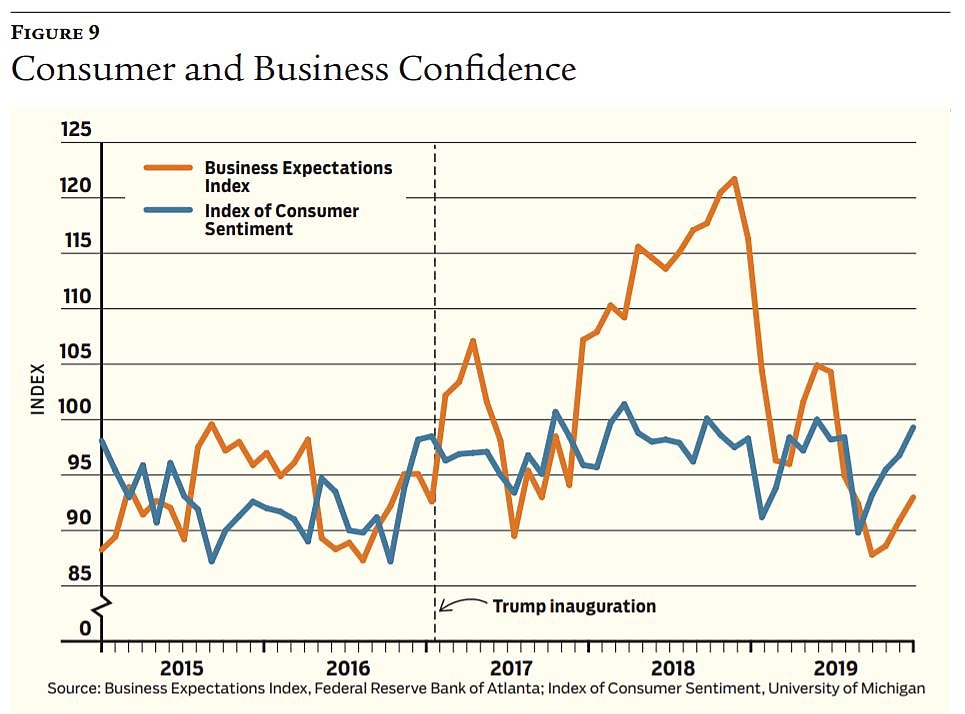

From 2017 to 2019, American consumer confidence was not exuberant and business confidence was volatile. As measured by the University of Michigan Index of Consumer Sentiment through monthly telephone interviews, confidence had been on a generally upward trend from the end of the Great Recession to 2015. But as Figure 9 shows, consumer confidence was roughly the same at the end of December 2019 as it was in January 2017, the beginning of the Trump presidency, and for that matter the same level as in 2015.

Figure 9 also shows the evolution of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Expectations Index (which is only available since 2015). Business executives and owners are polled once a month regarding their expectations of sales, employment, and capital investment over the next 12 months. During Trump’s first three years, business confidence showed much volatility. The most remarkable part of the chart is the one-year boom in business confidence starting in November 2018 and ending with a crash that may have been due in part to trade uncertainties.

During his first three years, Trump fostered the impression that he was running the economy. (Incidentally, a classical liberal would say the president is elected to run the government while the economy should be based on free enterprise.) When economic sluggishness appeared, however, he placed the blame on scapegoats: the Chinese, the Democrats, the media, etc. This is not surprising for a politician. This combination of simultaneously claiming to be in charge and denying responsibility has not contributed to consumer and business confidence.

Saying that his administration favored central planning would be an exaggeration, but Trump and his cohorts did show a tendency toward industrial policy without using the term. Industrial policy is a sort of ad hoc central planning. The Trump administration often appeared less a central planner than a disorderly, haphazard government. This is not a surprise either: as Friedrich Hayek argued, society and the economy are too complex for any central authority to understand, so central planning cannot be rational in any true sense. Trump’s personality and ignorance on economics aggravated this problem. Besides the supersonic turnover of personnel in his administration, examples of his frequent 180-degree turns in policy include his statements on the budget deficit mentioned above. Many other examples can be found.

Consider agriculture, a small economic sector (less than 2% of American employment) that Trump seems to favor because of the political support he receives from agricultural regions. His trade war with China hit agricultural exports hard. To rectify that, he handed out farm aid of $28 billion, which made up an estimated one-third of farm income in 2019. It is not true that “trade wars are good, and easy to win,” as he tweeted on March 2, 2018. Virtually any economist or economic historian could have told him that beforehand.

Trump’s irrational fixation on, and confusion about, the trade deficit resulted in wasteful policies that have not achieved the goals he intended. Figure 7 above shows that the U.S. trade deficit on goods and services did not decrease between the last year of Obama’s presidency and 2019; in fact, it increased by 23%. If we consider only the trade deficit on goods, Trump’s preferred metric, that deficit increased by 16%. Moreover, the trade deficit in goods with China, which was his main target, decreased by a mere 0.5%. He has attacked the world trade system, regulated American exporters, and imposed tariffs on American consumers, all for a measly 0.5% reduction in a meaningless number.

The promotion of manufacturing and its protection by tariffs illustrate not only mistaken trade policies during the Trump years but also the ineffectiveness of industrial policy—as well as the administration’s tenuous relationship with the truth. Trump claims in his February 2020 Economic Report of the President that “more than 500,000 manufacturing jobs have been created since my election. Rather than still shrinking, American manufacturing is now growing again.” The 500,000 figure is not false, but only 61,000 of those jobs have been created since December 2018. More important, real manufacturing output was stagnant during the whole year of 2019.

Many people think of policymaking as a rational exercise to promote the well-being of the greatest number. In the real world, nothing is further from the truth. Consider, for example, Trump’s thoughts on interest rates: In September 2015, candidate Trump opined that low interest rates were creating “a very false economy” and that savers “are getting just absolutely creamed.” In a May 2016 interview, one month before he won the Republican nomination, he declared, “I am a low interest-rate person.” Four months later, in September 2016, the Republican presidential candidate blamed then–Fed chairwoman Janet Yellen for keeping interest rates artificially low “because she’s obviously political and doing what Obama wants her to do.” But in an April 2017 interview with the Wall Street Journal, President Trump said, “I do like a low-interest rate policy, I must be honest with you.” After he appointed Jerome Powell to replace Yellen, Trump started to publicly and regularly attack him for pushing up interest rates. On August 23, 2019, Trump tweeted, “My only question is who is our bigger enemy, Jay Powell or Chairman Xi?”—referring to the Chinese president.

There is, of course, nothing wrong with changing one’s mind for reasons that one can explain cogently. But that is very different from turnarounds for political expediency or out of confusion. To say the least, such changes do not promote prosperity or liberty.

Whatever is the ideal level of interest rates (assuming there is such a thing) or the appropriate power and independence of a central bank, it is quite certain that a monetary policy subject to a politician’s short-term interests would have very detrimental effects. And it was certainly very risky to keep interest rates low during a period of economic expansion. In August 2019, at a time when the administration was boasting of a strong economy, the Fed adopted Trump’s latest stance on interest rates and started pushing them back down.

Lower interest rates may explain the good performance of the stock market in late 2019 (see Figure 3) despite all the uncertainties created by Trump’s trade wars and “mutable policies” (to use James Madison’s expression in Federalist No. 62). Low interest rates push up stock values because the benefit of keeping liquid assets (in government securities, savings deposits, or money-market funds) diminishes and stocks become more attractive.

Stranger in a Strange Land

Suppose a wholly impartial observer, trained in economics, visited the United States in December 2019 and, after looking around for a bit, was asked if the country was ready for a big economic shock. What would he have said?

I suspect he would have expressed concern about the federal government’s trillion-dollar deficit. He would have raised a red flag over the administration’s poor economic understanding, especially obvious in its disastrous trade policies. He would have worried that the Fed’s playing with interest rates under political pressure could be a harbinger of future inflation or stagflation. He would have noticed the central-planning mentality smoldering in D.C.

And if, besides being an economist, he was also a liberal (in the old sense of the word), he would have noted the damage done to liberty and free enterprise by the current and previous administrations as well as the other branches of government. He might have wondered whether most Americans still value such things. He certainly would have thought the federal government was very badly prepared to deal with an economic shock.

He would have been right.

Readings

- “Did Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Create Jobs and Stimulate Growth? Early Evidence Using State-Level Variation in Tax Changes,” by Anil Kumar. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Working Paper no. 2001, January 2020.

- Ten Thousand Commandments, by Clyde Wayne Crews. Competitive Enterprise Institute, 2020.

- “The Cumulative Cost of Regulation,” by Bentley Coffey, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Pietro Peretto. Review of Economic Dynamics, forthcoming.

- “The Economic Effects of Trade Policy Uncertainty,” by Dario Caldara, Andrea Prestipino, Matteo Iacoviello, et al. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Working Paper IFDP 2019–1256, 2019.

- “New China Tariffs Increase Costs to U.S. Households,” by Mary Amiti, Stephen J. Redding, and David Weinstein. Liberty Street Economics, May 23, 2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.