Last January, economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman tweeted something that I, as a business owner, found astonishing. He wrote, “There is no evidence—none—that regulation actually deters investment.”

I am not an economist by training, so perhaps this statement is true in aggregate across the economy. But I know from personal experience that it is not true at a granular level. My company has exited from certain businesses and locations in direct response to changing regulations, and I know others have as well. As a minimum, I believe that labor regulation is shifting investment away from businesses that employ unskilled labor and toward businesses that employ skilled labor or increasing levels of automation.

In my business, which staffs and operates public campgrounds, I employ about 350 people in unskilled labor positions, most at wages close to the minimum wage. I had perhaps 40 job openings last year and over 25,000 applications for those jobs. I am flooded with people begging to work and I have many people asking for our services. But I have turned away customers and cut back on operations in certain states like California. Why? Because labor regulation is making it almost impossible to run a profitable, innovative business based on unskilled labor.

Why is this important? Why can’t everyone just go to college and be a programmer at Google? Higher education has indeed been one path by which people gain skills and opportunity, but until recently it has never been the most common. Most skilled workers started as unskilled workers and gained their skills through work. But this work-based learning and advancement path is broken without that initial unskilled job. For people unwilling, unable, or unsuited to college, the loss of unskilled work removes the only route to prosperity.

The academic and public policy communities generally discuss the effects of government interventions into labor markets piecemeal, teasing out the effects of a particular regulation (such as an increased minimum wage) in isolation. As an entrepreneur, I don’t have that luxury; I must comply with literally hundreds of labor regulations simultaneously. En masse, these regulations have substantial negative effects on the ability of firms like mine to profitably employ workers, particularly the unskilled.

The purpose of this article is not to dissect the costs and benefits of any one particular regulation, but to survey the mass of regulation to demonstrate how the accretion of many different, presumably well-intentioned rules to protect workers can, in total, have exactly the opposite effect, making it difficult for companies to profitably employ unskilled labor and for those workers to develop and advance.

I will survey the field of labor regulation in four categories that roughly correspond to the effects these regulations have on business viability: 1) regulations that directly raise the price of labor; 2) regulations that add risk to hiring workers, and that can make unskilled workers particularly risky to hire; 3) regulations that add fixed costs for employers, increasing the minimum viable size of a company; and 4) regulations that limit business formation and growth by making it harder to pursue new and innovative labor models.

Regulations That Directly Raise the Price of Labor

The most easily identifiable regulations that hamper employers are those that impose direct costs on the hiring and retention of workers. Below are some prominent examples.

Minimum wage / Perhaps the most visible of these regulations are minimum wage laws. The federal government sets a minimum wage of $7.25 an hour (lower for workers who receive tips and higher for private workers making products or performing services for the government). However, many states and even cities have minimum wage laws that impose much higher requirements. The highest are Washington state at $11.50 an hour and Massachusetts and California at $11 an hour. Many of these state laws have escalators that are programmed to take the minimum wage to $15 over the next several years, while cities like Seattle are already at $15 an hour for larger employers. (See “A Seattle Game-Changer?” Winter 2017–2018.)

The minimum wage for certain activities like government construction projects is even higher. For example, under the Davis–Bacon Act a laborer who places and picks up orange cones around a federal highway project in California has a minimum wage of $43.97 an hour (and yes, the wage rules are that detailed).

Payroll taxes / Employers pay several percentage-based taxes on wages. Essentially sales taxes on labor, these are above and beyond similar taxes paid by the employee. Employers pay taxes for Social Security, Medicare, state and federal unemployment insurance, and—in some states like California—disability insurance.

While most of these taxes are fixed and predictable, unemployment insurance premiums can scale upward for businesses that are seasonal or have a lot of employee turnover (particularly given that many states are not very diligent about ensuring recipients are really looking for work, a supposed requirement of most unemployment benefits). In total, the employer share of payroll taxes starts at around 8% of wages. For businesses that hire a lot of transient or seasonal unskilled labor, these taxes are as high as 16% of wages.

Workers’ compensation / All states require employers to pay for workers’ compensation insurance for their employees, a no-fault insurance program that covers both lost wages and the cost of health care from workplace injuries (even those not resulting from employer negligence). When first implemented, workers’ compensation was inexpensive, with claims costs dominated by lost wage payments. As health care costs have increased, however, so too have premiums. Premiums generally are calculated as a percentage of wages and range from as low as 1% for skilled office workers, to 10% of wages for outdoor and maintenance workers, to as much as 50% of wages in certain injury-prone professions like roofing.

PPACA / The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), more commonly called “Obamacare,” represents an enormous and complex new set of regulations on businesses. Perhaps the most costly of these are the insurance coverage requirements. The law defines minimum health insurance policy features, and employers must pay penalties if they provide employees coverage below the minimum. Firms that provide insufficient health insurance (or no insurance at all) face penalties of $2,000–$3,000 per employee per year. Consider a worker earning $8 an hour for 2,000 hours a year (roughly full-time). This penalty acts as an effective 12%–19% additional tax an employer must pay for employing the worker, while providing compliant health insurance can cost even more.

Mandatory employee leave / Both federal law and most states have requirements to provide workers in a variety of situations (e.g., illness or pregnancy) with unpaid leave and full rights to return to their same job after the leave is over. California has a mind-boggling 14 categories of leave that employers must provide, including: paid sick leave, kin care, pregnancy disability leave, voting leave, jury duty and court attendance leave, crime victims leave, leave for victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking, organ donor/bone marrow donor leave, family crisis leave, volunteer civil service/emergency responder leave, Civil Air Patrol leave, military spouse leave, military and reserve duty leave, and school visitation leave. In most cases, providing this leave seldom creates a big problem for businesses, though it can create some awkwardness (e.g., what does one do with good workers who filled in for employees on leave, fire them when the leave is over?).

More recently, though, states have been adding requirements for paid rather than just unpaid leave. States like California and Arizona, for example, require employers to give workers up to three days a year of paid sick leave, an equivalent of a 1.2% tax on wages. Led by the District of Columbia, activists are pushing states to require companies to provide up to eight weeks of paid family leave. If that benefit were to be taken once every two years, it would be the equivalent of a 7.7% tax on the wages of young people in their reproductive years.

Effects / Taken together, these regulations substantially increase the minimum cost of employing even the least-skilled workers. In a location with a $15 minimum wage, the actual all-in cost per hour with taxes and minimum benefits might be as high as $21 an hour. It is very hard to run a profitable business employing unskilled workers at these sorts of costs.

Consider my business for example. A typical campground we operate requires perhaps two hours of labor per week per campsite, so an increase from the federal minimum wage to a $15 minimum wage might add $22 a week per site in wages and related costs. Since we typically make $2 to $3 per week in profit per site, most or all of these extra costs will be passed on to our customers. Given typical campsite occupancy of 2.5 days per week and $23 a night camping rates, customers would have to bear a 40% price increase to cover a $15 minimum wage. In the end, we increase prices where we can and exit the business where we cannot.

Our relatively low net income margin of 5% (for comparison, in 2016 Microsoft and Google had margins of 23% and 27% respectively) is not unusual for companies that depend on low-skill labor. Almost by definition, firms that depend on low-skill workers to deliver their product or service have difficulty establishing barriers to competition. It’s difficult to do anything uniquely innovative when much of the work is performed by employees with limited skills. As soon as one firm demonstrates there is money to be made using low-skill workers in a certain way, it is far too easy for competitors to copy that model. As a result, most businesses that hire low-skill workers will have had their margins competed down to the lowest tolerable level.

Thus, as in my campground example, the least likely response to regulation-induced labor cost increases is a reduction in profits because profits have already been competed down to the minimum necessary to cover capital investment and keep owners interested in the business. The much more likely responses will be increased prices and reduced employment. In the long-term, companies will substitute capital for labor, reducing employment even further.

Regulations That Increase Business Risk

But regulations that directly impose costs are not the only ones that hamper employment. Another category of troublesome regulation imposes increased risk, which in turn harms firm profits and viability. Here are some examples.

Liability for bad employee behavior / The legal system places much of the liability for an employee’s actions not on the employee but on the firm’s owners. A business can put in place policies and training mandating the proper treatment of other employees and customers, but if one knucklehead out of a company’s dozens or hundreds of employees decides he is going to harass someone or discriminate against certain races or religions, the owners (and not the employee) can and will get sued. Such lawsuit defenses are expensive even when the firm ultimately prevails; I have never seen a suit for even the most absurd of claims settled without spending at least $20,000 in legal expenses.

Reduced hiring information / Given firms’ liability for employees’ bad behavior, employers reasonably would like to vet employees quite diligently. However, regulations increasingly limit the information one can gather in the hiring process, greatly increasing the risk of hire. Examples include “Ban the box” (which limits employers’ ability to ask about past criminal convictions), restrictions on using credit checks on potential employees, and more recent restrictions against asking employees about their past salary and employment status. In addition, litigation has also made reference-checking much harder because many firms will not respond to reference checks because of fear of lawsuits over negative references.

Restrictions on terminating employees / In several ways, regulations increasingly make terminating poorly chosen employees more difficult. For example, equal employment rules give employees who fall into a number of legally protected classes (e.g., certain races, ethnicities, and genders) enhanced rights to file lawsuits or other legal complaints for things like unfair termination. It seems that no person in history has ever believed that his or her firing was fair, so employees may challenge even well-justified terminations. Termination can thus be costly and time-consuming, as extra steps are often taken in the termination process in anticipation of potential future legal action.

Another increasingly frequent source of legal challenges to terminations has been created by “whistleblower” laws. The law protects employees who report potentially illegal corporate activities to regulatory or law enforcement agencies. As a business owner, I want my employees to report impropriety because I want to fix the problem. However, over the past several years, firms have started to see some employees, when anticipating termination for poor performance (and even after such termination), make accusations against the company so they can then challenge the termination as unjust retaliation for the claims they have made.

Firms’ liabilities for the actions of a poorly selected employee are rising, yet regulations are making it harder for employers to get good hiring information and to terminate employees who present threats to the workplace.

Effects / It used to be that the worst human resource risk a company faced was hiring employees who simply did not justify their salary. However, given the current body of regulation, any poorly selected employee is a potential ticking bomb who, through bad behavior with customers or other employees, could tie up the company for years in expensive litigation or regulatory actions. But as a firm’s liability for the negative activity of a poorly chosen employee rises, regulations are making it harder to get good information to make better hiring choices, while simultaneously making it harder to terminate employees who were poorly chosen and present threats to the workplace or customers. When employers begin to look at their employees not as valuable assets but as potential liabilities, fewer people are going to be hired.

One potential way employers can manage this risk is to shift their hiring from unskilled employees to college graduates. Consider the risk of an employee making a racist or sexist statement to a customer or coworker (and in the process creating a large potential liability for the company). Almost any college graduate will have been steeped in racial and gender sensitivity messages for four years, while an employer might have an hour or two of training on these topics for unskilled workers. Similarly, because good information on prospective employees—credit checks, background checks, reference checks, discussions of past employment and salary—all have new legal limitations, employers who hire college graduates benefit from the substantial due diligence universities perform in their admissions process.

Regulations That Increase Fixed Costs

Besides adding to the direct and indirect costs of each employee, government regulations impose a number of fixed costs on employers. These further dampen employment by affecting firm viability. Consider the following examples.

Payroll and PPACA compliance / Payroll and the rules that govern it—wage and hour laws, sick day accruals, tax payments to multiple authorities, garnishments, W‑2s—have become so complex that most companies cannot manage their own payroll. In certain states, for example, companies can be fined or sued for violations as small as using the wrong font on payroll checks. In response, businesses—even small ones—pay thousands or tens of thousands of dollars a year for third-party payroll firms to manage this process. Similarly, in 2016 new rules went into effect requiring companies to put in place extensive tracking systems for their employees’ health insurance status and eligibility, including detailed annual reporting that must be sent to every employee and the government. Many firms like mine have been forced to pay a vendor at considerable expense to do this paperwork.

Reporting / My small company is deluged with reporting requirements to the government, many of which touch on employment. For example, my firm is required to collect the race, ethnicity, and gender of employees and report this information annually to the government. In 2016, the federal government announced that this annual reporting requirement will, in 2018, be expanded from tracking employees in about 80 race/job/gender combinations to tracking them in 3,600 race/job/gender/income categories. (This expansion has been suspended by the Trump administration—at least for now.)

It is an unusual day in my office when I do not get yet another letter from some state or federal agency—the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, its state-level equivalents, labor departments, census bureaus, tourism boards—that wants something filled out on my business. Whether it be the number of labor hours worked in Florida or the number of employees who received first aid in California, some government agency somewhere always wants more data.

The micro-regulation minefield / Beyond the more well-known regulations we have mentioned, states and municipalities have hundreds, even thousands, of other detailed employment-related laws under which even a conscientious employer can find itself facing enormous fines and legal penalties. There are far too many of these to list, but I will discuss one example: the lunch break law in California.

In California, employers have an affirmative responsibility to make sure employees take their lunch break. If the employee chooses to work through the break or even works through the break despite explicit employer mandates not to do so, the employer is still liable for penalties. My company tried several approaches to documenting when employees worked through lunch by choice (say, to get more hours of work or to go home earlier), but all eventually failed. When we allowed employees to work through lunch at their own request, we were later successfully sued for giving them this opportunity.

Ex post facto law / Compliance with a bewildering array of regulations is hard enough, but many regulations are poorly worded or don’t take into account the full variety of working arrangements that exist in the private sector. One is often forced to guess exactly what is legal. In the case of California’s lunch break law, for example, the “safe harbor” for compliance shifted several times as the rules were tested in court cases. Frequently companies find that compliance strategies they thought were legal have to be reworked as regulations are clarified in the courts. As a result, my company pays thousands of dollars each year to attorneys who review our employee handbook, compliance systems, timesheet process, and a myriad of other details for necessary changes. In California, we do this twice a year because it is so hard to keep up with the state’s massive amount of regulatory change.

Presumption of guilt / While nominally most labor law conforms to the same criminal and civil legal standards of guilt and innocence that obtain in the rest of the justice system, in practice employers often bear the burden of a presumption of guilt with regulatory bodies. We must prove ourselves innocent.

I will offer one example from my own experience. My firm had a routine labor audit by a state labor department. Mostly it went well, but somehow one timesheet for one week had been lost for a single employee. The investigator asked the employee to estimate his hours worked that week. On every other timesheet for years, he had reported 30–40 hours per week. For the missing timesheet, the employee retroactively claimed 128 hours, or a bit over 18 hours a day. This was obviously absurd and any reasonable person would have rejected this estimate as opportunistic and exaggerated. But my company eventually had to pay for 128 hours (40 regular hours and a whopping 88 hours of overtime) because we could not prove absolutely that the worker did not work what he claimed.

Effects / Most of these regulations impose fixed costs and do not increase the cost of hiring decisions at the margin. In other words, if I already am paying for a payroll system, an onboarding system, and an injury reporting system, hiring one more person does not cost me much more. However, all these expenses, by raising the fixed overhead costs of a business, tend to increase the minimum size a business must be to remain viable. For example, $20,000 in fixed costs to manage these regulatory issues is likely a trivial expenditure for a multi-million-dollar corporation, but for a company with revenues of only $100,000 a year it can be backbreaking. Perhaps even worse for many small businesses, the only person who can usually manage this compliance work is the owner, causing the one person who typically drives growth and improvement in the business to spend much of his or her time worrying about compliance issues instead.

I am embarrassed to admit that this mass of regulation has probably helped my business. As one of the two or three largest firms in a niche industry, we have been able to absorb these costs while most of our smaller competitors have left the business. Fifteen years ago I used to find myself bidding against small family firms operating in just a single location; now, I only see competition from the larger multi-location firms like mine.

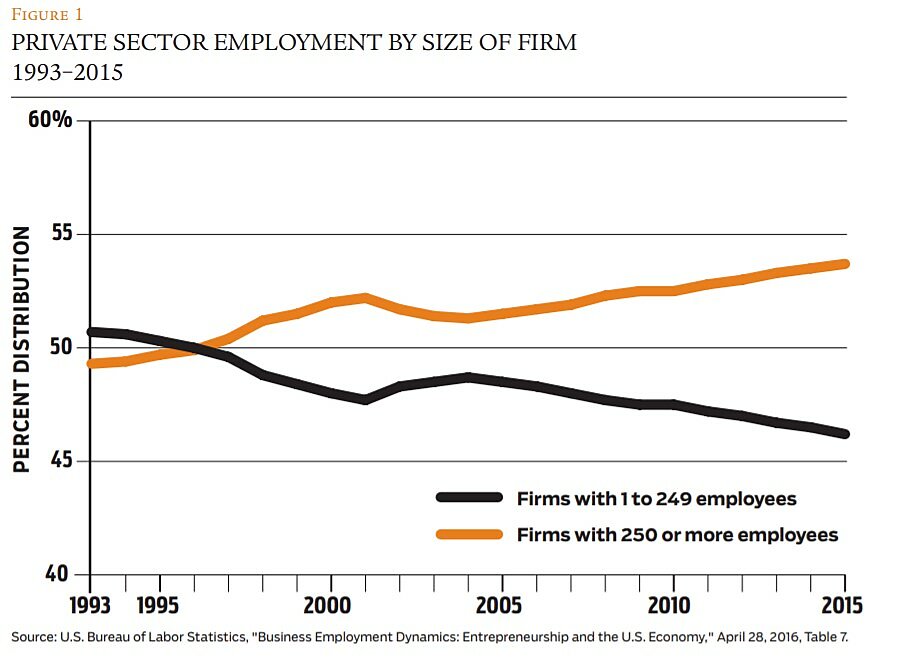

On a macro scale, we would therefore expect that as these fixed costs imposed by regulation rise, employment will shift from smaller to larger companies. This is indeed what the United States has experienced for over two decades, as shown in Figure 1.

One reason for this decline is that, according to the U.S. Small Business Administration, since 1992 most of the new small businesses formed have had no employees at all. These zero-employee companies are a predictable result of the increasing regulatory costs of hiring because these sorts of business owners are generally exempt from much of labor regulation. A company in which only the owners provide labor is substantially less expensive to operate than a company with even one employee.

The decline in the relative share of employment at small businesses and the decreased job creation from new small businesses have a disproportionate effect on unskilled labor because small businesses have always been a particular source of opportunity for less educated workers. In 1998, before most of these declines in small business employment share, 52.2% of small business employees had high school diplomas or less, while just 44.5% of larger company employers had this level of education.

Regulations That Discourage New and Innovative Business Models

In addition to the costs discussed above, regulations can also restrict the use of new and different business models, thereby hurting firm flexibility and innovation. This is bad for business, consumers, and the economy.

Workweek and overtime rules / All states have established a 40-hour work week and require at least 150% of a worker’s wage rate—“overtime pay”—be paid for time worked over those 40 hours. Certain states have even more restrictive rules. For example, California requires overtime pay after the fifth day of work or after the 8th hour in any given day, no matter how many hours were worked the rest of the week. Massachusetts requires overtime always be paid on Sundays. In California and some other states, employers are required to give an unpaid break for lunch of at least a half hour in the middle of a shift. However, if this legally mandated break becomes longer than one hour, this work then falls under split-shift law and the employer must pay a penalty of one hour of pay to the employee for each day it occurs.

Minimum salary / In addition to minimum wages, the federal government and many states set what is effectively a minimum salary. This is the lowest salary at which employees are no longer required to report their work hours and thus are no longer required to receive overtime pay. In 2016 the Obama Labor Department raised this limit, more than doubling it from $23,660 to $47,476. Suddenly, millions of junior managers taking their first steps toward higher trust and responsibility were faced with filling out a timesheet again. (In August of last year, a U.S. District Court blocked implementation of this rule. The Trump Labor Department is now reconsidering it.)

Shift scheduling / A number of cities and states have passed or are seriously considering restrictions on how employers set work schedules. Seattle’s new law is typical: it requires employers to set shift schedules two weeks in advance, and applies penalties if employees are asked to work more, less, or different hours than shown on the schedule two weeks earlier. Employers also face restrictions and possible penalties when assigning employees to shifts at specific times, days, or locations of work that don’t match the employees’ preferences.

Effects / Often my employees ask me why labor law will not allow practices that would make a lot of sense in our business for both employer and employee. I tell them to imagine workers in a Pittsburgh factory, punching a time clock, working 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday, working within sight of their supervisor, taking their breaks in the employee lunch room. This is the labor model regulators and legislators had in mind when writing the bulk of labor law. Any other labor model—seasonal work, part-time work, working out of the home, working unpredictable hours, telecommuting, working away from a corporate office or one’s supervisor, the gig economy—become square pegs to be jammed in the round hole of labor law.

A few years ago my company was audited by a state labor department in California over workers who clean remote trailheads. One issue was the state requirement, discussed previously, concerning workers’ meal breaks. In reviewing employee timesheets, the auditor asked to see written schedules so she could compare the scheduled time to the timesheets. I told her there were none. She was incredulous; how could there be no written schedules? How could she make sure we had not denied anyone a lunch break? I said we had no written schedules because employees schedule themselves—it is better for the company and way better for the employee. Employees could schedule their break—in fact, all their work—for any time they wanted so long as the work got done. Despite this being perfectly sensible both to me and my employees, the auditor’s final recommendations included a notation that we should have formal work schedules, effectively asking that we take away the agency and autonomy we had given our workers.

While many businesses struggle to serve diverse customer needs within the restrictions of wage and hour laws, even more limiting to business flexibility are the new shift scheduling laws like the ones in Seattle. These regulations will make running a retail service business, at least one like my own, almost impossible. There is no way one can predict exact staffing needs two weeks in advance. In my business, it is not at all uncommon for a large group to suddenly show up without reservations to occupy a dozen or more campsites we expected to remain empty. How can this possibly be handled if substantial penalties are imposed by the government for paying extra help to serve these unexpected customers? Even ignoring changes in customer behavior and acts of God like major weather events, many last-minute changes to shift schedules are caused by the employees themselves. One employee gets sick, has car trouble, has an emergency, or just does not show up, and someone has to be called out to fill in the gap (particularly if first-line supervisors are no longer salaried but subject to overtime).

These rules do not just limit business flexibility in hiring hourly workers, they also make it harder to advance them. Most employers who hire unskilled workers promote much of their management from these front-line employees. Every one of the 60 managers in my company, including my chief operating officer, began in the company cleaning bathrooms. Walmart claims that 70% of their store management started in an entry-level job stocking shelves or running the register. Unfortunately, the rules increasing minimum salaries will make it harder for such unskilled workers to advance.

Certainly companies will still hire first-line supervisors even if they must be paid hourly. But the entire nature of these jobs will change. Some differences are psychological; for better or worse, management thinks of salaried workers differently than hourly workers. The same, I can say from personal experience, is true of the front-line supervisors themselves, who see a switch back to punching a time clock to be a demotion.

And some differences are real. Salaried workers can try to demonstrate that they are worthy of promotion by working extra hours and showing initiative by taking on extra tasks, something hourly workers simply would not be allowed to do for fear of incurring overtime charges. Without these minimum salary rules, young junior managers might work 60 hours a week to impress management with their diligence and dedication, signaling they were ready for promotion. With the minimum salary rules, employers will only have clock-punchers for junior managers. And once the most junior salaried workers make at least $48,000 a year, companies will more likely consider hiring college graduates for these positions rather than promoting from their internal pool of promising unskilled workers, both because of the higher price and risk and because there will no longer be a way for unskilled workers to demonstrate that they are worthy of this trust.

Conclusion

Fifteen years ago I started my current service business. I love my company and my employees. But if I had it all to do over again, I would never start a business based on employing unskilled labor. The government makes it too difficult, in far too many ways, to try to make a living employing unskilled workers. Given a new start, I would find a business with a few high-skill employees creating a lot of value.

And I don’t think I’m alone. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, there was a wave of successful large businesses built on unskilled labor (e.g., ServiceMaster, Walmart, McDonalds). Today, investment capital and innovation attention is all going to companies that create large revenues per employee with workers who have college educations and advanced skills. Only 4% of the employees at Apple, for example, have less than a college degree.

Even in large service-sector companies that employ unskilled labor, much of their investment today is in finding ways to reduce their reliance on that labor. I remember a number of years ago when the Chili’s restaurant chain started putting little electronic displays on their tables. At first the displays just showed advertising and I thought they were an annoying waste of space. But over time the chain began using the devices first to accept payment for one’s food and more recently to take food orders. They are progressively eliminating the need for most of their wait-staff. Every major restaurant chain is doing the same thing: investing in technology to eliminate unskilled workers. Why bother trying to figure out how to serve a rapidly evolving customer demand with workers who are limited by government in a hundred different ways in how and when they can labor? A website or iPad never sleeps, never sues, never needs a lunch break (let alone documentation of that break), never has to have overtime, and doesn’t have its labor taxed.

The one exception to this lack of new opportunities in the unskilled labor market has been the gig economy, particularly companies like Uber and Lyft that provide work opportunities for hundreds of thousands of unskilled laborers. But Uber is the exception that proves the rule: it has succeeded in large part by making an end-run around most of the costly and restrictive labor regulations discussed in this article. Uber drivers are (at least as of this writing) independent contractors providing services to consumers to whom they are connected via the Uber app. Uber gives their drivers a tremendous amount of flexibility: they can set their own work schedule and shifts. Numerous regulated practices we have discussed, for which regulators fear the danger of employer abuse (e.g., lunch break timing, shift length, work-week length, split-shifting), are all entirely within the employee’s control.

Uber thus provides a growing number of employment opportunities for unskilled workers. But it’s not clear that this ultimately helps these workers move up the economic ladder. There is currently no clear path at firms like Uber or Lyft for drivers to advance—as cashiers can at Walmart—into supervisory positions. And while I have called Uber drivers unskilled labor (since most of us are able to drive even before we complete high school), it is not a viable work option for the very poor who don’t have the resources for cars and insurance.

Thus the mass of government labor regulation is making it harder and harder to create profitable business models that employ unskilled labor. For those without the interest or ability to get a college degree, the avoidance of the unskilled by employers is undermining those workers’ bridge to future success, both in this generation and the next.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.