Born with the 16th century, the modern era brought the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, and economic growth at a rate that the world had never seen before. Northwestern University economic historian Joel Mokyr’s A Culture of Growth traces this wondrous transformation as it occurred in the West’s economy.

Mokyr leads the reader on a fascinating voyage that starts about the year 1500 and ends three centuries later. To trace the origins of the modern economy, he studies the culture that led to the Industrial Revolution, and the reciprocal influence of culture on social institutions and individual incentives.

For too many social scientists, “culture” is a sort of black box that they invoke to explain social and economic transformation, but in doing so they really say next to nothing. Recently, economists have become interested in this black box and Mokyr attempts to offer a look inside it.

He defines culture as “a set of beliefs, values, and preferences, capable of affecting behavior, that are socially (not genetically) transmitted and that are shared by some subset of society.” He argues persuasively that cultural change is necessary to explain the 18th century Enlightenment and the unending flow of technological innovations that followed with the Industrial Revolution.

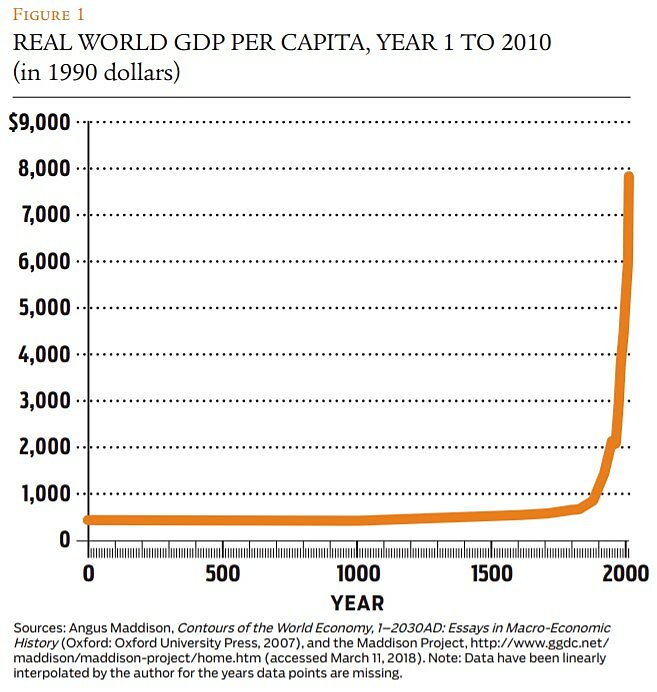

Modern growth / To appreciate what Mokyr sets out to explain, consider Figure 1, which I compiled from data by the late economist Angus Maddison. (No figure or table appears in Mokyr’s book.) Note that I used linear interpolations to cover the long stretches of time for which Maddison’s estimates are not available. These interpolations explain why a catastrophic event like the Black Death of the 14th century doesn’t make a blip in the line.

From Year 1 of the Common Era until the 18th century, human living standards scarcely changed. World gross domestic product per capita inched up slightly from less than $500 per year during the first millennium, to $616 in 1700, and $712 in 1820. Then, production and income exploded. In less than two centuries, GDP per capita multiplied by more than 10, reaching $7,814 in 2010 (the last year available in this series). These figures are averages over the whole world, estimated in constant 1990 dollars. In the United States, GDP per capita (again in constant 1990 dollars) reached $30,491 in 2010.

This one dramatic transformation is the story of mankind from an economic standpoint. In comparison, the last century’s Great Depression barely registered.

The resulting effect on living conditions has been dramatic. During the 17 centuries between Year 1 and 1700, the world population multiplied a paltry 2.7 times. In the following three centuries, it multiplied by more than 10. And recall that, since 1820, real GDP per person also multiplied by 10. Since the mid-19th century, life expectancy at birth has increased from 30 years (which is probably the maximum it had reached over all of previous history) to more than 70 years today. Literacy jumped. These were only some of the consequences of the “Great Enrichment.”

Starting in the late 18th century, “Smithian growth” was replaced by “Schumpeterian growth.” The former refers to economic growth through more efficient markets, which Adam Smith observed and promoted; the latter works through inventions, entrepreneurial innovations, and “creative destruction,” to use Joseph Schumpeter’s term.

Mokyr argues that this stunning new growth cannot be explained by religion, which played an ambiguous role in the acceptance of new ideas, even factoring in the Reformation. Nor can it be explained by an increase in human capital—education and knowledge—because capital increases had occurred before but had failed to launch self-sustained, explosive growth. Besides, he notes, “the great engineers and inventors who made the Industrial Revolution were rarely well educated.” Instead, they were feeding on a whole infrastructure of new knowledge.

The crucial factor in the Great Divergence shown on the chart was a new belief in progress. It required “thinking outside the box” and a “willingness to rebel against accepted practices and norms.” A new culture of growth developed that made explosive growth possible.

Culture / How can we explain the appearance of this culture of growth? Mokyr adopts an “evolutionary approach to culture” borrowed from anthropology and evolutionary biology. Such an approach, he argues, helps understand the cultural change that created the institutions that made possible the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. Cultural evolution selects the most efficient cultural elements or features, as opposed to selecting individuals. This sort of evolution is rendered even more potent by the capacity of individuals to be persuaded and to consciously choose their beliefs. “Choice-based cultural evolution” leads to a more rapid spread of innovations.

Mokyr borrows from a large number of scholars in different fields. For example, he relates this culture of growth idea to Deirdre McCloskey’s “bourgeois values.” Surprisingly, however, nowhere in A Culture of Growth does Mokyr cite Friedrich Hayek. Many readers would like to know what, if anything, differs between Mokyr’s and Hayek’s evolutionary approach. Both authors warn against a too-servile use of the methods of biology in social analysis, but both find evolutionary theory useful. As I mentioned in a recent review of his final book, The Fatal Conceit, Hayek argued that an evolutionary approach to social science was actually pioneered by Adam Smith and Adam Ferguson in the 18th century, well before Charles Darwin used it in biology. (See “Against Tribal Instincts,” Spring 2018.)

Cultural entrepreneurs add to the menu of beliefs, values, and preferences among which individuals can choose. Mokyr devotes a chapter to each of two major cultural entrepreneurs who spread the ideas that would lead to the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution: philosopher Francis Bacon and scientist Isaac Newton. Bacon and Newton both emphasized observation and empirical verification as opposed to the mere exegesis of ancient texts. “Bacon’s heritage,” Mokyr writes, “was nothing less than the cultural acceptance of the growth of useful knowledge as a critical ingredient of economic growth.”

Useful knowledge is a crucial concept in A Culture of Growth. Exemplified by the French Encyclopédie and numerous technical textbooks published all over Europe, useful knowledge is scientific knowledge applied to production. It is related to the Enlightenment idea that “the human lot can be continuously improved by bettering our understanding of natural phenomena.” Newton thought that science could only explain how things work—as opposed to their metaphysical nature—which implies that it could produce useful knowledge.

Why culture changed / It is not totally clear what were the causal factors, as opposed to favorable circumstances, that led to the new cultural belief in progress. Perhaps the point is that the different factors co-evolved (in an evolutionary sense) to produce cultural change.

Mokyr seems to propose four major factors:

First, there are the cultural entrepreneurs such as Bacon and Newton, as well as many others who walked in their steps. They contributed to changing not only the scientific culture, but also the political culture. Perhaps Mokyr could have given more attention to the political evolution toward individual rights, the rule of law, and the division of power in the state.

A second factor is the shock of new knowledge. In the late 16th and the 17th centuries, countless scientific theories of the Ancients—from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, from Aristotle to Aquinas—were disproved by new observations with the help of instruments such as the telescope and microscope. Ptolemy’s vision of the universe yielded to the new observations and theories of Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler. Long-distance voyages and geographic discoveries also changed the image of the world.

Third, governments were unable to stop the spread of new knowledge. As David Hume noted, the political fragmentation of Europe prevented governments from suppressing the new ideas they deemed destabilizing and dangerous. “In the political environment of a politically fragmented world,” Mokyr observes, “progress cannot be blocked by the coercion of a few reactionary powers.” Not only was Europe fractured among multiple states, but even monasteries and universities were “quasi-autonomous self-governing bodies.” “Members of the ‘creative classes’ … moved all over the Continent.”

Tyranny thus suffered a “coordination failure.”

Republic of Letters / A fourth factor—a major one— was the “Republic of Letters,” which emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries and stimulated the creation and spread of new ideas. As Mokyr puts it, the “unique combination of political fragmentation with the pan-European institution of the Republic of Letters holds the key to the dramatic intellectual changes after 1500.”

The Republic of Letters was perhaps the most extraordinary spontaneous development in Europe. It was an informal and transnational society of scholars—philosophers, scientists, and other intellectuals—who criticized, developed, and discussed ideas through correspondence and publications. Their correspondence, made publicly available, amounted to an ongoing peer-reviewed journal. The “citizens” of the Republic of Letters followed strict rules such as replying to all letters, giving due credit to the originators of ideas, and putting all knowledge in the public domain. They privately produced the public good of new knowledge.

The small elite constituting the Republic of Letters formed the backbone of a free market in ideas. This market was both competitive and cooperative, Mokyr notes:

There is no contradiction between the coexistence of such harmonious and competitive forces, as an analysis of any market demonstrates. Economists have understood since Adam Smith that the glory of the market system is this unique combination.

The Republic of Letters included most of the great scholars of the time: men such as Erasmus, Bacon, Voltaire, Hume, Smith, Newton, Descartes, Condorcet, and Spinoza, along with numerous lesser-known figures. It covered many European countries, including Great Britain, France, Italy, the Low Countries, Germany, and Spain. Its transnational character was essential: “At least in theory,” Mokyr observes, “a citizen of the Republic of Letters was supposed to be a person without a fatherland.”

The Republic of Letters was critical and antidoctrinaire. According to Mokyr, “The liberal ideas of religious tolerance, free entry into the market for ideas, and belief in the transnational character of the intellectual community were essential to Enlightenment thought.”

It is true that many if not most scholars depended on the patronage of kings and nobles. But the Republic of Letters served as an informal accrediting process, assuring that the subsidized scholars were not impostors or puppets. The selfish competition between patrons for the best scholars contributed to freedom of thought and speech, which was basically established by the end of the 17th century.

The market for ideas remained largely private. The printing press, invented in the 15th century, played a big role. Printing houses spread all over Europe. Besides producing periodicals and books, they “were ‘international houses’ where dissident foreigners could find shelter and a meeting place.” Mokyr notes that “in Europe, by and large, encyclopedias and reference books were the product of private enterprise, sometimes published very much against the will of authorities powerless to stop them.”

The Republic of Letters “turned out eventually to be an institution unique in human history and a key to understanding where the long road that led to modern economic growth began.” Ideas matter. Free markets too.

Reactionary forces / Reactionary forces were represented by such figures as Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, but they were more and more isolated as modern times rolled on. Here again, the reader would have appreciated a reference to Hayek—in this case, the latter’s distinction between “true” and “false” individualism and between British and continental liberalism.

Many of Hayek’s false individualists were associated with the Enlightenment and thus with Mokyr’s culture of growth. To what extent did both “true” and “false” individualism play a role in creating the modern economy? Did these two strands of individualism have more in common than Hayek led us to believe?

The “battle of the books,” or querelle des Anciens et des Modernes, that agitated Europe was emblematic of the clash between old and new ideas. By the end of the 17th century, the moderns had won. The cultural change that had brought scientific contestability, useful knowledge, human progress, and Lockean rights bloomed in the 18th-century Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution that started toward the end of that century. The entanglement of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution is a major thread in A Culture of Growth.

The book ties together many components of our understanding of modernity. For example, the victory of the moderns would end “the folly of mercantilist notions that placed the state (and not the individual) as the ultimate object of society.” Today’s reader cannot but reflect that Enlightenment values are now under siege.

Why not in China? / Mokyr raises the perennial question of why the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution happened in Europe but not in Asia, particularly in China. He takes much care not to assign the blame for this to an inferior Asian culture compared to Europe. Is this partly a reflection of the political correctness that seems required today when discussing such issues, or is it just scholarly prudence? In any event, we should not forget that the citizens of the Republic of Letters were skeptical of conventional wisdom and were not very politically correct in their own times.

The Industrial Revolution that happened in Europe, Mokyr argues, was a rare and unexpected event. Like evolutionary surprises, it could have not happened, or it could have happened elsewhere. “The advantage of models of cultural evolution,” he writes, “is that they are contingent and concern ex ante probabilities rather than deterministic causal models.” An industrial revolution required progress that—instead of fizzling out as had happened in previous examples, including in the East—would start a “positive-feedback self-reinforcing explosive technological trajectory.”

“What was missing in China,” Mokyr explains, “was a high level of competitiveness, both in the market for ideas and at the level of political power.” Despite a vibrant intellectual life and many technological discoveries (including in shipbuilding and clockmaking), China’s centralized government and its conservative bureaucracy—maintained by a stifling examination system—choked progress. Barriers to entry in the market for ideas were high. Another scholar quoted by Mokyr, Eric Baark of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, observed that scientific knowledge was hampered by “political correctness.”

Because it did not have the necessary culture and institutions, China missed both an industrial revolution and an enlightenment à la European:

The importance of the Enlightenment for Europe’s subsequent economic development goes beyond its impact on the exploitation of useful knowledge for material progress, the essence of the Industrial Enlightenment. It also codified and formalized the kind of institutions any society needed to maintain its technological momentum: the rule of law, checks and balances on the executive, and severe sanctions on more blatant and harmful forms of rent-seeking. … The historical irony is that prosperity as it was experienced after 1750 required creative destruction, the very opposite of social and economic stability.

After it discovered China, the West eagerly borrowed Eastern ideas and imported goods. For example, “chinaware” was exotic and much in demand, and did not disguise its foreign origins. On their side, the Chinese elite were not interested in “cultural appropriation” from the West, so the country remained insular and mired in the past. It was soon lagging far behind the West in economic growth.

Culture in Mokyr’s sense includes philosophical beliefs. A Culture of Growth shows that philosophical beliefs in China, despite some diversity, lacked several ingredients of Western philosophy. Perhaps we can go further and say that China lacked the individualistic philosophy that was necessary for intellectual enlightenment and economic progress. (See “Confucius, Autonomy, and Capitalism,” Winter 2017–2018.)

If one values individual flourishing, all this looks to me like saying that Chinese culture and institutions were inferior to European culture, even if Mokyr does not cross that bridge. It might be worth crossing if we want to draw lessons for our times. The death of Mao Zedong in 1976 was followed by an explosion of economic and cultural entrepreneurship in China. Economic competition soared. Production and the standard of living there started growing somewhat like in 19th-century Europe.

After three decades of this regime, many observers thought that a Chinese Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution were under way, although serious analysts like Ronald Coase and Ning Wang realized that this movement would soon require a liberation of the market for ideas. (See “Getting Rich Is Glorious,” Winter 2012–2013.) As the Chinese government has veered back toward authoritarianism, the prospects for continuing growth have dimmed considerably, even if this does not yet show in economic statistics. Those who, often for invalid protectionist reasons, fear the economic growth of China can relax.

Role of freedom / Mokyr paraphrases the late science historian Reijeer Hookykaas in saying that, at the time of the Republic of Letters, “commercial and industrial cities were intellectually dynamic, far more so than university towns.” The coevolution of ideas, commerce, and industry up to the explosion of economic growth in the 18th and 19th centuries reminds us of how intellectual freedom, economic freedom, wealth, and individual autonomy are interrelated.

A related fact is how “in the North American colonies and the United States, the odd mixture of Puritan values with elements of the French and Scottish Enlightenment were decisive in setting the culture of the young republic in the 1780s.” Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin were two emblematic figures of the Enlightenment.

If cultural change explains the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution, has cultural change really been explained? Or have we once again credited the black box? I am not sure. But this complex and rich book certainly provides many keys to the answer. It strongly suggests that limits on government and a free market in ideas created the conditions necessary for the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, and the Great Enrichment. After reading this book, chances are that you won’t look at the economic, social, and political world in quite the same way as before.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.