All too often, those who focus exclusively on the Internet era have paid too little attention to the lessons of the legacy of regulated industries. A mature academic literature exists analyzing the challenges faced in the past when applying common carriage to industries such as railroads, trucking, airlines, natural gas and oil pipelines, electric power distribution, and traditional telephone service. Nondiscrimination in rates—a key component of common carriage regulation—is difficult to enforce when products vary in terms of quality or cost and does not allow charging different prices to consumers whose demand elasticities differ, a practice that can increase economic welfare. Common carriage also provides weak incentives to economize, raises difficult questions about how to allocate common costs, and deters innovation. At the same time, it facilitates collusion by creating entry barriers, standardizing products, pooling information, providing advance notice of any pricing changes, and allowing the government to serve as the cartel enforcer. Three historical examples—early alternatives to local telephone companies known as competitive access providers, the detariffing of business services, and Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP)—provide concrete illustrations of how refraining from imposing common carriage regulation can benefit consumers.

The Growing Competitiveness of Broadband Internet Access

The most important traditional rationale for the regulation of common carriers is the presence of monopoly power. But the fact that the market for last-mile broadband is becoming increasingly competitive is steadily undermining that rationale.

The most recent data collected by the FCC indicate that as of December 2012, 99 percent of U.S. households live in census blocks with access to two or more fixed line or mobile wireless broadband providers capable of providing the benchmark speeds of 3 Mbps downstream and 768 kbps upstream. Some 97 percent have access to three or more providers. Faster service tiers are also becoming more competitive. For example, 96 percent of U.S. households have access to two or more providers offering service at the higher standard of 6 Mbps downstream and 1.5 Mbps upstream, and 81 percent have access to three or more. Even at the highest tier reported (10 Mbps downstream and 1.5 Mbps upstream), 80 percent have access to two or more providers and 48 percent have access to three or more.

The biggest change in the market is wireless broadband. Although service based around 3G technologies remains relatively slow, wireless broadband providers have begun to deploy a 4G technology known as Long Term Evolution (LTE), which typically delivers much higher speeds. Although some observers have expressed skepticism that LTE can ever be a substitute for fixed line broadband, recent studies cited by the FCC indicate that as of May 2013, the LTE offerings of Verizon, AT&T, and T-Mobile were providing average download speeds of 12–19 Mbps, with peak download speeds averaging between 60 Mbps and 66 Mbps. Late-arriver Sprint is also providing download speeds that average 6 Mbps and peak speeds that average 32 Mbps. And on the horizon is the next-generation wireless technology known as LTE Advanced, which is already being deployed in other countries and is capable of delivering speeds of up to 150–300 Mbps.

The FCC's most recent report on wireless competition indicates that as of October 2012, 98 percent of U.S. residents live in census blocks served by two or more 3G wireless providers, with 92 percent being served by three or more and 82 percent being served by four or more (in addition, of course, to the services offered by fixed line providers). The 2012 data underrepresent the current competitiveness of the market. As of the end of 2012, Verizon had extended LTE to only 83 percent of its service area, AT&T reached only 51 percent, and Sprint and T-Mobile had not yet begun their LTE deployments. By the end of 2013, Verizon had completed its LTE deployment and served 96 percent of the U.S. population, AT&T reached 80 percent, and Sprint and T-Mobile covered roughly two-thirds of the country. The market should become even more competitive by the end of 2014, with AT&T projected to complete its buildout and reach 96 percent of the population and with Sprint and T-Mobile planning to cover 80 percent. Even smaller, regional providers such as Leap, US Cellular, and C-Spire are beginning to deploy the technology. Once those wireless providers complete the buildout of their networks, the market should be even more competitive.

Although these markets are not perfectly competitive, empirical studies indicate that markets with three firms are workably competitive, with most of the competitive benefit occurring with the entry of the second or third firm and minimal benefits resulting from entry in markets that already have three to five firms. One must also bear in mind that regulation is costly and typically falls short of replicating the performance of a perfectly competitive market. Regulation thus turns on a comparison of second-best outcomes. Although the poor performance of unregulated monopoly justifies bearing the significant costs of regulation, an unregulated oligopoly performs sufficiently better and at some point tips the balance in favor of deregulation.

The case for imposing common carriage regulation based on market power is even harder to make with respect to Internet protocol (IP)–based services other than broadband Internet access. The markets for VoIP, cloud services, wireless devices, and online mapping services are all subject to robust competition. Even though the leading search engines and social networking platforms have relatively high market shares, the Federal Trade Commission recently concluded that the fact that switching costs are low obviates the need for regulatory intervention.

The Shortcomings of Nondiscrimination

Those who remain unconvinced that broadband Internet service is workably competitive and instead believe that substantial market power exists will continue to be concerned that companies will use that power to implement pricing practices that will harm consumers. In particular, they may advocate imposing regulation mandating nondiscrimination to prevent providers from replacing flat-rate, unlimited-access pricing with policies that charge different customers different prices for different products.

The academic literature on common carriage reveals that while mandating nondiscrimination sounds good in principle, it is difficult to implement in practice. Ascertaining whether prices are discriminatory requires far more than simply seeing whether firms are charging customers the same price. Charging two customers the same price, for example, could be discriminatory if providing the product or service to those customers differs in terms of quality or cost. In addition, prohibiting providers from charging customers different prices based on the intensity of customers' preferences for the product, rather than differences in quality or cost, would foreclose what economists call "Ramsey pricing," which can be an efficient way to recover fixed costs.

Differences in quality / Any nondiscrimination mandate must evaluate whether any price differences are justified by variations in product quality. As a result, common carriage regimes work best for commodities for which product quality does not vary. Classic examples include water, natural gas, and electric power.

For Internet-based services, the sources of variations in quality are vast. As an initial matter, quality of service on broadband networks varies along as many as four dimensions: bandwidth, delay, jitter, and reliability. Whereas voice communications on the telephone network operated only within a narrow range of service parameters, the services that Internet providers offer and that applications demand can vary widely. Indeed, the FCC has long cited the benefits from allowing more diverse offerings as one of the reasons for declining to subject enhanced services to common carriage regulation.

Moreover, the congestion control mechanisms embedded in the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) cause end users communicating with distant locations to receive less bandwidth than those communicating with nearby locations because of the simple fact that transmission sessions with shorter feedback loops increase their sending rates more rapidly than sessions with longer feedback loops. Further difficulties arise from the fact that quality of service is also the joint product of how other subscribers are using the network. If everyone generates traffic at the same time, everyone receives lower quality of service in ways that could justify cost differentials but that are difficult to observe.

That is why many observers regard Internet-based services as particularly ill-suited to common carriage regulation. For example, cloud computing is based on networking services that are highly differentiated and nonfungible in terms of service level and functionality, with the needs of different customers varying widely.

Differences in cost / Regulators who implement nondiscrimination mandates must also carefully scrutinize production technologies and costs to see if price differences are justified by differences in cost. The problem is that modern Internet access is provided through a wide range of production technologies—including cable modem service, fiber-based service, digital subscriber line (DSL) service, and wireless broadband—that have different cost structures. As a result, cost differentials are likely to be pervasive.

Even more importantly for our purposes, within the same production technology the cost of providing service can vary widely between customers. In network industries, the primary expense is the fixed cost needed to establish the principal line providing service to a neighborhood, which is large compared to the cost of connecting individual subscribers to that line. The principal determinant of unit cost is the density of subscribers in any particular area. An increase in density permits fixed costs to be amortized over a larger number of subscribers.

One would thus expect subscribers in more densely populated areas to pay less than those in areas in which population density is sparser. Most regulatory authorities mandate rate averaging to ensure that all customers pay the same amount regardless of location. For example, public utility commissions have generally set rates for local telephone service that are uniform across entire states even though the real costs of providing service vary. In this way, somewhat ironically, the traditional implementation of common carriage violates fundamental principles of nondiscrimination. Stated somewhat differently, by implicitly requiring urban subscribers to cross-subsidize the connectivity of rural subscribers, a uniform rate structure violates the fundamental principle of nondiscrimination. Indeed, in its 2002 ruling in Verizon Communications Inc. v. FCC (535 U.S. 467), the Supreme Court recognized that imposing such cross subsidies in the name of promoting universal service represented “state-sanctioned discrimination.”

Implementing nondiscriminatory pricing is also greatly complicated by the manner in which the cost of providing Internet service varies over different parts of the day and different locations. Congestion costs arise when multiple subscribers use the network at the same time. The actual costs of providing service can thus vary widely from moment to moment depending on actual usage. In addition, technologies such as cable-modem service and wireless broadband aggregate traffic locally, making subscribers’ experience highly susceptible to the usage levels of their immediate neighbors. This means that congestion can vary geographically, with one node being saturated while an adjacent node is not. Any pricing scheme that was truly nondiscriminatory would thus vary from minute to minute as well as from place to place.

Such a regime would face significant implementation problems. The localized nature of the Internet means that each network provider is aware only of local conditions. It has no systematic way of discerning the congestion levels in its downstream partners when it hands off traffic. Although those channel partners could share that information, network providers typically jealously guard data about the configuration of their networks and the loads they carry. In addition, network providers would have to provide extensive new systems to monitor and propagate information about network usage and pricing at a timescale relevant to actual costs. Moreover, although permitting traffic levels to grow without any change in price so long as the network is slack would reflect actual costs, such an approach would cause network resources to become locked out as soon as they became saturated. Such sharp discontinuities in network behavior can lead to wide-scale disruptions and inefficient usage of network resources. Finally, subscribers’ ability to adjust to dynamic pricing is rather limited. Indeed, research indicates that consumers cannot process pricing plans that divide the day into more than three parts.

All of those considerations are likely to make nondiscrimination mandates difficult to implement. They are also likely to cause real-world prices to deviate from nondiscriminatory prices.

Demand-side price discrimination / Like all products characterized by high fixed costs and lower marginal costs, services provided by network industries confront a fundamental pricing problem. Academic scholarship on networks and regulators has long recognized that price discriminatory regimes such as Ramsey pricing can alleviate that problem.

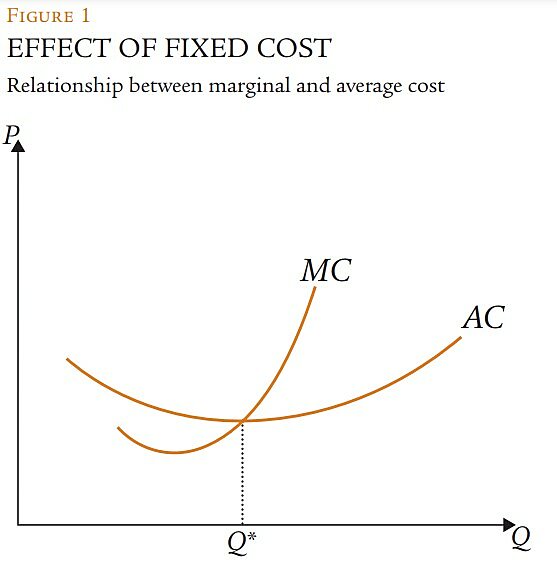

As initial investments are amortized over increasingly large volumes, average costs decay exponentially. Sources of scale economies are typically exhaustible, however. As production volumes increase, the cheapest sources of raw materials become scarce. At some point the economies of scale become diseconomies of scale and variable costs increase. Eventually, variable cost increases result in average cost increases (indicated in Figure 1 by Q*). The larger the fixed costs, the higher the quantity at which this crossover point will occur.

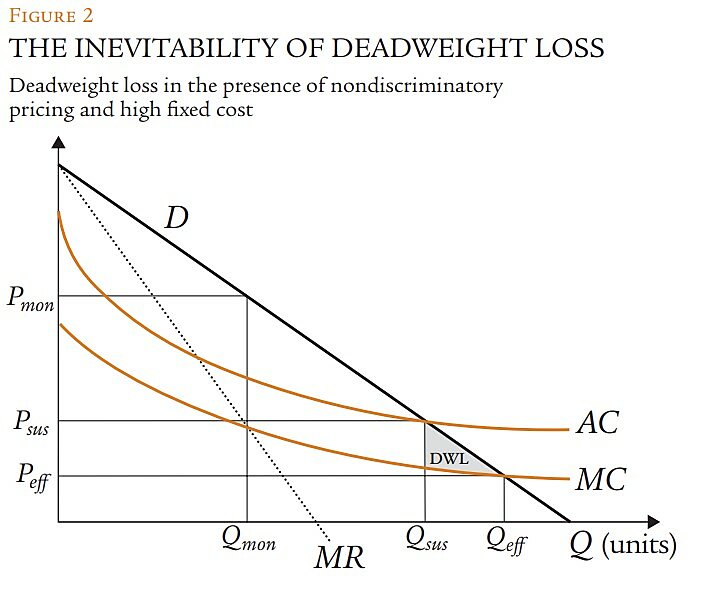

The maximization of economic welfare must satisfy two conditions. First, price must equal marginal cost, otherwise further increases in production would cause economic welfare to decrease. Second, price must equal or exceed average cost, otherwise the producing firms will go out of business. It is easy to identify prices that both equal marginal cost and equal or exceed average cost if industry demand is sufficiently large to permit multiple firms to produce volumes that exceed Q*. If, on the other hand, the total industry volume is less than Q*, no price-quantity pairs exist that both equal marginal cost and equal or exceed average cost. Any prices that equal average cost and thus permit the firm to break even necessarily exceed marginal cost and create some degree of deadweight loss.

Monopolists seeking to maximize their profits will produce where marginal revenue equals marginal cost (represented in Figure 2 by Pmon and Qmon). At that point, prices are inefficiently high in that they exceed marginal cost. The traditional policy response is to regulate rates to drive down the prices charged by the monopolist. To be sustainable, however, the price must permit the monopolist to recover its production costs, which requires that the prices equal or exceed average cost. Absent price discrimination, the lowest sustainable price that equals or exceeds average cost is represented in Figure 2 by Psus. The fact that Psus exceeds marginal cost means that it is inefficient and leads to a shortfall in production equal to the difference between Qsus and Qeff. The monopolist could serve consumers between Qsus and Qeff by charging them prices that fall below average cost and compensating by charging other customers prices that exceed average cost.

It is for this reason that economic textbooks regard price discrimination as a necessary condition to maximizing economic welfare in industries, like telecommunications, that require substantial fixed-cost investments. Indeed, this is the insight underlying Ramsey pricing, which allocates a higher proportion of the fixed costs to those consumers who are the least price sensitive (and thus will reduce their purchases only minimally even though prices exceed marginal cost) and a lower proportion of the fixed costs to those consumers who are the most price sensitive (and who will decrease their consumption sharply in response to any increase in price).

The FCC has been reluctant to permit Ramsey pricing in the context of unbundling out of concern that it would raise prices on those elements that are the most difficult to replicate, which it believed was inconsistent with the statute’s focus on promoting competition. One study estimated the welfare loss stemming from the refusal to implement Ramsey pricing for local telephone service at approximately $30 billion per year.

Rate-of-Return Regulation: A Primer

Even though broadband is workably competitive and nondiscriminatory pricing is more difficult to implement than most people realize and sometimes inefficient, some people still favor rate regulation. This section describes the mechanics of how it has been implemented historically and the negative consequences that have resulted.

Rate-of-return regulation focuses on the cost of the inputs according to the formula R = O + Br, where R is the total revenue the carrier is permitted to generate (sometimes called the revenue requirement), O is the carrier’s operating expenses incurred during that particular rate year (such as taxes, wages, energy costs, and depreciation), B is the amount of capital investments that must be recovered over multiple rate years (also known as the “rate base”), and r is the appropriate rate of return allowed on the capital investment.

Once the total revenue requirement is set, prices are set for each service in a manner designed to allow the firm to satisfy that requirement. If there is only one product and one rate class, rates are determined simply by dividing the total revenue requirement by the number of units consumers are expected to demand. If, as is usually the case, the regulated firm offers multiple products (e.g., local and long distance services) and more than one class of service (e.g., residential and business services), the calculus is considerably more complex. Regulators then monitor the overall revenue and profit earned by the regulated entity to make sure that unexpected variations do not cause major deviations from the targets.

Determining the proper rate base / One of the most longstanding challenges of rate regulation is how to value capital expenses that comprise the rate base (B). Establishing the proper way to value the costs that make up the rate base has proven to be one of the most difficult problems in economic regulation. Indeed, in Verizon Communications Inc. v. FCC, the Supreme Court characterized the word “cost” as “a chameleon,” “virtually meaningless,” and “protean.”

The biggest controversy has surrounded whether the rate base should be calculated based on historical or replacement cost. In 1898, the Supreme Court’s landmark case of Smyth v. Ames (169 U.S. 466) held that the Constitution entitled regulated firms to rates based on the “fair value” of their assets. And by fair value, the Court meant the assets’ current market value as measured by replacement cost. This was soon met by a vigorous defense of historical cost by Justice Brandeis in the 1923 case Missouri ex rel. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co. v. Public Service Commission (262 U.S. 276). More recently, regulatory authorities have begun to use an even more stringent form of replacement cost, exemplified by the FCC’s adoption of Total Element Long-Run Incremental Cost (TELRIC), used to implement rates set under the Telecommunications Act of 1996. This calculation was based not on the replacement cost of the assets actually purchased, but rather on the replacement cost of a hypothetical network composed of the most efficient components if the network were rebuilt from scratch today.

The debate between historical and replacement cost is not merely academic. The choice between them can have dramatic implications for both the rates paid by consumers and the returns earned by companies. In a deflationary environment or one in which technological innovation is driving costs down, replacement cost implies lower rates and historical cost implies higher rates. But in an inflationary environment, such as World Wars I and II, replacement cost causes rates to increase, while historical cost implies lower rates. In addition, the uncertainty surrounding replacement-cost determinations, particularly those made around hypothetical combinations of assets, makes rate hearings costly and maddeningly inconsistent.

The result is that, aside from TELRIC, regulatory authorities have stopped their endless fights over how best to determine replacement cost and generally relied on more stable and less arbitrary measures of historical cost. Historical cost is not without its own drawbacks, however. Guaranteeing a return on outdated technology can reward obsolescence. One of the most difficult administrative problems associated with common carriage regulation thus remains unresolved.

Lack of incentive to economize on costs / A second challenge with rate-of-return regulation is that regulated firms have no incentive to economize on costs. The cost-plus nature guarantees firms a return on their expenditures, which dampens their incentive to economize and their incentive to invest in cost-reducing improvements. Firms subject to rate regulation may also avoid deploying new technologies that would render their investments obsolete before they recover those costs.

Conversely, once investments are sunk, regulated firms are vulnerable to regulatory opportunism in which regulators find expenditures imprudent and deny recovery. The risk of such expropriation can cause firms to underinvest systematically in their networks.

Determining the proper rate of return / Determining the appropriate rate of return often proves even more difficult than determining the appropriate rate base. The regulator must decide whether to focus on the regulated entity’s cost of capital or that of represented industry participants, which are typically themselves regulated and thus do not represent independent observations. The regulator must determine whether to evaluate the current risk level or the one at the time the capital expenditures were made. In determining the weighted average cost of capital, regulators must take into account the different tax treatment of each instrument. They must also decide whether the risk premium includes protection against inflation or reflects pioneering new services that are not yet proven. This determination is complicated by the fact that small differences in rates of return can have dramatic effects on the total revenue that the carrier is allowed to generate.

In the end, setting rates of return is as much about a political bargain allocating benefits between consumers and firms as it is about economics. Thus, it should come as no surprise that firms that operate in multiple jurisdictions often find large differences in the rate of return they are permitted to earn.

Setting prices and allocating common costs / The dynamism of Internet-related markets makes it more difficult to set prices in an efficient manner. As noted earlier, the most straightforward way to generate individual prices is to divide the revenue requirement by the projected demand. This yields good results when industry demand and market shares are relatively stable. When demand is uncertain, however, prices may give the regulated firm a windfall if demand unexpectedly increases, or they may fail to meet the revenue requirement if demand unexpectedly falls.

Another classic problem associated with rate-of-return regulation is the reduction in pricing flexibility. As the user base becomes more heterogeneous, users will want an increasingly diverse range of ever more customized products. Some consumers may be willing to pay higher prices for more features or higher quality. Others may wish to buy a no-frills version at a cheaper price. The creation of new products will inevitably require regulatory approval of new price-product combinations. The inevitable lag means that regulation will cause the product offerings and prices to be increasingly out of step with consumer demand. The faster the rate of change, the more significant this wedge will become.

Regulated prices suffer from an even more fundamental problem. They deviate from marginal cost, the central policy prescription of microeconomics. Of course, when fixed costs are high, it is impossible to charge prices that both equal marginal cost and equal or exceed average cost. In that case, the efficient outcome would charge in inverse proportion to the elasticity of demand (Ramsey pricing). Again, the average-cost approach to pricing embedded in rate-of-return regulation is at odds with this outcome. Regulatory innovations, such as price caps, were supposed to solve many—if not all—of those problems, but failed to live up to their promise.

Setting rates of return is as much about a political bargain allocating benefits between consumers and firms as it is about economics. Firms that operate in different districts often have different rates of return.

Facilitating collusion / A final drawback to common carriage regulation is that it has long been recognized to facilitate collusion. This is because common carriage tends to create entry barriers, standardizes products and prices, pools information about price and product changes, and puts the government in a position to mandate adherence to particular prices.

Barriers to entry: Common carriage typically imposes access controls. Both federal and state law require interstate carriers to obtain a certificate of public convenience and necessity before constructing or extending any new facilities. At best, the clearance process delays entry. At worst, it can block entry altogether, as evidenced by Congress’s enactment of a provision prohibiting states from using the certificate process to forestall the emergence of competition.

In addition, firms may use common carriage regulation as an entry barrier. It has long been recognized that industry-wide regulation can benefit incumbents (despite the additional costs of compliance) if new entrants and fringe players find it harder to bear the regulatory burden. Indeed, some firms have actively sought regulation in order to create entry barriers.

Standardization of products and pricing: Cartels are much easier to form and enforce when products are homogeneous. When products are uniform, any coordination designed to reduce competition need only focus on a single dimension: price. When products are heterogeneous, however, any price agreement must take into account all of the ways that products can vary. This makes agreements both harder to reach and to police. If products are so customized that each is individualized, cartel cheating may be almost impossible to detect or prevent.

Another practice that tends to undermine oligopoly discipline is unsystematic price discrimination. Secret price discrimination is one of the best ways for cartel members to cheat. Cartels also function best when demand is more or less constant, which in turn helps ensure that prices remain stable.

Common carriage has the effect of facilitating collusion along each of those dimensions. Standardizing both products and prices makes cartel agreements easier to reach and any defection from the cartel easier to identify. At the same time, entry restrictions and the ratemaking process can help stabilize demand.

Pooling of information and advance notice: Common carriage has the effect of making all pricing information visible and easily available to all other industry participants. In addition, it requires every provider to announce in advance to all of its competitors any planned changes in prices or product offerings. The loss of lead time dampens the incentive to make price cuts.

By requiring that prices conform exactly to the published rate, common carriage prohibits any deviation from the established price. Under the filed rate doctrine, regulated entities cannot cut their prices.

Pooling of pricing information has long been recognized as a facilitating practice that makes it easier to form and maintain a cartel. As the FCC recognized:

Tariff posting also provides an excellent mechanism for inducing noncompetitive pricing. Since all price reductions are public, they can be quickly matched by competitors. This reduces the incentive to engage in price cutting. In these circumstances firms may be able to charge prices higher than could be sustained in an unregulated market. Thus, regulated competition all too often becomes cartel management.

Such information is particularly helpful to cartels if that information pertains to changes in product or changes to price.

Ability to use government to enforce cartel pricing: Finally, cartels need some means to enforce the cartel by preventing price cutting. Cartels often find enforcement difficult because the members must not reveal to the government that they are colluding.

Common carriage provides for an open and legal way to enforce prices. By requiring that prices conform exactly to the published rate, common carriage prohibits any deviations from the established price. Under the filed rate doctrine, regulated entities cannot cut their prices. Moreover, to the extent that these are enshrined in regulation, any compliance with these prices is immune from antitrust scrutiny.

In addition, common carriage gives any member of the public the right to challenge any proposed change to a tariff. Firms have routinely used this authority to oppose price reductions proposed by their competitors. As such, tariffing creates the same opportunity for interference as competitor suits in antitrust law, where a less efficient competitor can try to prevent its rival from competing on the merits.

The imposition of common carriage thus facilitates collusion in a wide variety of ways. The danger of expediting the formation and maintenance of a cartel provides another important reason to resist common carriage.

Lessons from Regulatory History

The argument that Internet consumers are better served by markets than by common carriage regulation is based on more than just theory. In this last section, I review three recent examples that describe how common carriage regulation has hurt rather than helped consumers.

Competitive access providers / Long before the enactment of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, competition began to emerge in local telephone service. The arrival of fiber optics fostered the emergence of a new type of company known as the competitive access provider (CAP). CAPs initially focused on offering long distance bypass services, which allowed corporate customers to place long distance telephone calls without having to access the Bell System’s local telephone facilities. The eventual expansion of CAP networks to cover the entire core business districts of major metropolitan areas made it possible for CAPs to offer local telephone service in direct competition with the incumbents.

CAP-provided services possessed many advantages over those provided by the incumbent local telephone companies. First, CAP networks tended to employ more modern technology, which allowed them to offer a greater range of features and a more attractive price structure than could the incumbent local telephone companies. Unlike the incumbents, moreover, because CAPs were not subject to common carriage regulation, they were not required to provide uniform services according to published tariffs approved by the FCC. As a result, they were able to respond more quickly to market demands and to tailor pricing and terms of service to each customer’s needs. Lastly, the untariffed nature of CAP services also allowed them to avoid the cross subsidies embedded in the system of access charges created by the FCC.

Detariffing business services / The emergence of competition in portions of the telecommunications industry has provided some impetus toward eliminating tariffing requirements. State public utility commissions have also been detariffing business services to permit providers to tailor their offerings to individual customers’ needs. Individual businesses have begun to demand increasingly specialized services. As a result, state public utility commissions have had to entertain a growing tide of petitions seeking permission to deviate from the published tariffs.

A similar move is taking place in local residential service, as competition from wireless services is leading local phone companies to request detariffing of rates (see “What Happens When Local Phone Service Is Deregulated,” Fall 2012). For example, Qwest asked the Idaho Public Utility Commission to deregulate its rates in light of the emergence of effective competition. The Idaho Public Utility Commission rejected the petition because it was not persuaded by the evidence that mobile telephony has become the functional equivalent of traditional wireline telephony. Over time, state public utility commissions have largely deregulated local phone service for businesses and have begun to deregulate residential local phone services as well.

VoIP / The final case is interconnected VoIP. When VoIP was first introduced, it was largely exempt from all of the obligations imposed on local telephone service. This has changed over time. Beginning in 2005, VoIP has become subject to universal service, e911, disability access, number portability, and service outage reporting requirements.

What is interesting is the extent to which VoIP differs from conventional telephony. Unlike traditional telephone service, VoIP rides on a packet network that transmits data on a best efforts basis. As a result, it is much less reliable than conventional telephony. Because it rides on a general instead of a specialized network, it also consumes more bandwidth.

At the same time, it is different from other types of Internet applications. The Internet was originally designed around the TCP protocol. It ensured reliability by requiring that every receiving host send an acknowledgement to the sending host for every packet it received. If the sending host did not receive a packet within the expected time frame, it would simply resend it. This approach presumed that reliability was more important than expediency and that if a packet was dropped, the next available window was best used for resending a dropped packet instead of sending a new one.

While this approach worked well for applications such as e‑mail and web browsing that were not particularly sensitive to delays of a fraction of a second, the Internet’s protocol designers soon discovered that this design did not work well for packet voice. The delays waiting for the retransmission timer to expire and for the packet to be resent rendered the service unusable. Like all real-time applications, packet voice is also more sensitive to jitter. As a result, the protocol architects created a new protocol called the User Data Protocol (UDP) that would send packets without waiting for acknowledgements.

VoIP thus differs in important ways from both conventional telephony and traditional Internet applications such as e‑mail and web browsing. Specifically, it needs different services from and imposes different burdens on the networks on which it rides. Common carriage runs the risk of lumping it together with applications that are quite different. Doing so would potentially harm VoIP and interactive IP video, with the effect on video being greater because of its greater demand for bandwidth. As a result, I would resist the call by French regulators for Skype to register as a conventional telephone company as well as the proposal before the United Nations’ International Telecommunications Union to bring Internet interconnection into the regime used to settle international telephone calls. Even more importantly, homogenizing the networks’ services may threaten future applications that may place demands on the network that are different still.

Conclusion

With increasing frequency, common carriage is being invoked as a potential basis for regulating Internet-based services. The tone of these invocations often suggests that this recommendation represents a return to principles that are well established and relatively uncontroversial.

Anyone calling for a return to common carriage must grapple with the reality that common carriage has been the subject of extensive criticism for the past half-century. The existence of controversy does not by itself prove that imposing common carriage would necessarily be bad policy. It does, however, suggest that proponents of common carriage should actively engage with the institution’s recognized shortcomings. Such a large corpus of scholarship simply cannot be ignored.

Readings

- “A Clash of Regulatory Paradigms,” by Christopher S. Yoo. Regulation, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Fall 2012).

- “Annual Report and Analysis of Competitive Market Conditions with Respect to Mobile Wireless, including Commercial Mobile Services,” 16th Report, produced by the Federal Communications Commission. Federal Communications Commission Record, Vol. 28 (2013).

- “Cloud Computing: Architectural and Policy Implications,” by Christopher S. Yoo. Review of Industrial Organization, Vol. 38 (2011).

- “Entry and Competition in Concentrated Markets,” by Timothy F. Bresnahan and Peter C. Reiss. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 99 (1991).

- “Fastest Mobile Networks 2013,” by Sascha Segan. PCMag, June 17, 2013.

- “Is It Time to Eliminate Telephone Regulation?” by Robert W. Crandall. In Telecommunications Policy: Have Regulators Dialed the Wrong Number? edited by Donald L. Alexander; Praeger, 1997.

- “Network Neutrality and the Economics of Congestion,” by Christopher S. Yoo. (6) Georgetown Law Journal, Vol. 99 (2006).

- “Protecting and Promoting the Open Internet,” published by the Federal Communications Commission. May 15, 2014.

- “The Design Philosophy of the DARPA Internet Protocols,” by David D. Clark. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communications Review, Vol. 18 (August 1988).

- “What Happens When Local Phone Service Is Deregulated?” by Jeffrey A. Eisenach and Kevin W. Caves. Regulation, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Fall 2012).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.