The Food Safety Modernization Act, signed in 2011, directs the FDA to adopt regulations requiring facilities that manufacture, process, pack, or hold food—including animal food—to implement preventive controls to ensure that the food is not “adulterated.” Last October, the FDA proposed a regulation to implement that mandate for both pet food and livestock feed.

The proposed regulation contains two principal requirements: First, most animal food manufacturing facilities must implement a set of “current good manufacturing practices” intended to prevent contamination of animal food. Second, those facilities must develop a written food safety plan, conduct a hazard analysis, implement preventive controls for hazards that are reasonably likely to occur, monitor the controls, verify that they are effective, take any corrective actions, and maintain records on all of those efforts. That is, the facilities must implement a Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) system.

The proposed regulation does establish criteria to exempt certain “qualified facilities” and activities from the costly second requirement. The FDA sought comment on the dollar threshold to use in defining “very small” businesses that would be given that exemption.

Unfortunately, the Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) accompanying the proposed regulation provides scant assessment of the nature, cause, and significance of the animal food problem the regulation seeks to solve. In the absence of such an assessment, the RIA has no basis for estimating the benefits of the proposed rule or the benefits associated with the alternative definitions of “very small” business. It estimates the costs of the alternatives, but since the differential benefits of the alternatives are unknown, there is no way to determine whether the more restrictive definitions of “small business” produce benefits that justify the additional costs.

Indeed, the RIA fails to prove that the regulation would produce any significant benefits at all. Our own estimate of the monetized benefits suggests that the proposed rule’s costs—as estimated by the FDA—of between $87 million and $129 million annually substantially outweigh our best estimate of $17 million in annual benefits.

What’s the Problem?

The very first principle of regulation enunciated in Bill Clinton’s still-operational Executive Order 12866 governing regulatory analysis and review is that “each agency shall identify the problem that it intends to address (including, where applicable, the failures of private markets or public institutions that warrant new agency action) as well as assess the significance of that problem.” To accurately identify the problem at hand, the FDA should have explained why marketplace incentives are inadequate to produce the optimal level of animal food safety and presented evidence that its explanation is sound. To assess the significance of the problem, the FDA should have demonstrated that the problem is large and widespread, not just the consequence of a few bad actors or a few anecdotal problems in the marketplace.

Instead, the RIA merely hypothesizes that producers and consumers may not have sufficient information about the safety attributes of animal foods. It suggests that neither legal liability nor product branding may be sufficient to produce the optimal level of food safety. The section of the RIA titled “Need for Regulation” does suggest that market failure could be the cause of this hypothesized problem. To its credit, the RIA consistently states that safety “may” be below the optimal level and that government regulation of food safety “may” be able to improve social welfare. However, the section presents no evidence about the actual state of consumers’ or producers’ knowledge about animal food quality or contamination, no evidence about the effectiveness of the legal system or branding in promoting animal food safety, and no information about how much the safety of animal food deviates from the optimal level. In fact, given the relatively small number of incidents of tainted animal food that the FDA cites, it is entirely possible that safety is currently at the optimal level.

Some of the hazard and recall information the FDA presents actually undermines the argument that the proposed regulation would solve a significant problem that is not already addressed by marketplace incentives and legal liability. The RIA offers three figures showing that animal food recalls can be costly to manufacturers: In 2008, a pet food company paid $3.1 million to settle a lawsuit stemming from aflatoxin contamination. The largest-ever pet food recall cost the industry more than $50 million; in its wake, demand for pet foods not affected by the recall increased, suggesting that consumers penalize firms that produce unsafe food and reward those that produce safe food. The RIA also estimates that animal feed recalls cost the industry approximately $32.6 million annually in direct product losses. Such figures suggest that the marketplace creates substantial incentives for the industry to keep animal food safe.

“Nevertheless,” the analysis concludes, “animal food recalls continue to occur, suggesting that market incentives are not sufficient to motivate manufacturers and others processing and handling animal food to adequately control hazards that can cause recalls.” This statement is a non sequitur. It is equivalent to claiming that the optimal level of risk is zero, which implies that pet and livestock owners (or perhaps our broader society) would be willing to pay an infinite amount to eliminate the last little bit of risk of animal food contamination so that there would be zero recalls. The RIA presents no evidence to demonstrate that this implausible assumption is true.

The FDA seems to believe that the optimal level of risk is zero, which implies that pet and livestock owners would be willing to pay an infinite amount to eliminate the last little bit of risk of animal food contamination.

The fact that some recalls occur does not prove that a market failure exists. The FDA articulated a market failure that is theoretically possible, but it did not demonstrate that the market failure actually exists.

Significance not demonstrated / The closest thing to evidence of a widespread adulteration problem the RIA provides is a recitation of statistics and examples of hazards found in animal food, human illnesses traced to salmonella contamination in animal food, and animal food recalls. At most, this information proves that mistakes do happen and sometimes hazards turn up in animal food. The statistics on hazard incidents and recalls are presented without any contextual information showing whether they are frequent or infrequent, or what percentage of the market they constitute. As a result, it is impossible to conclude from the RIA whether adulteration of animal food is a large or widespread problem.

Statistics in the RIA reveal that the majority of pet food recalls in recent years resulted from one event: the economically motivated decision of two Chinese companies to intentionally add melamine to pet food ingredients that were shipped to the United States. This one incident accounted for more than 60 percent of all Class I pet food recalls and 80 percent of recalls for chemical contamination between 2006 and 2010. Given that one such instance accounts for the majority of pet food recalls, it’s quite possible that a much more limited regulation, inspection, or enforcement initiative targeted at bad actors could eliminate most of the adulteration problem without forcing an entire industry to adopt costly new procedures. The presence of a few bad actors in a market is not the same thing as a widespread market failure. Alternatively, it may be that the Chinese manufacturers did not know that melamine was a problem. If not, the remedy would be for the FDA to produce better information to inform manufacturers about what is and is not acceptable as an ingredient in pet food.

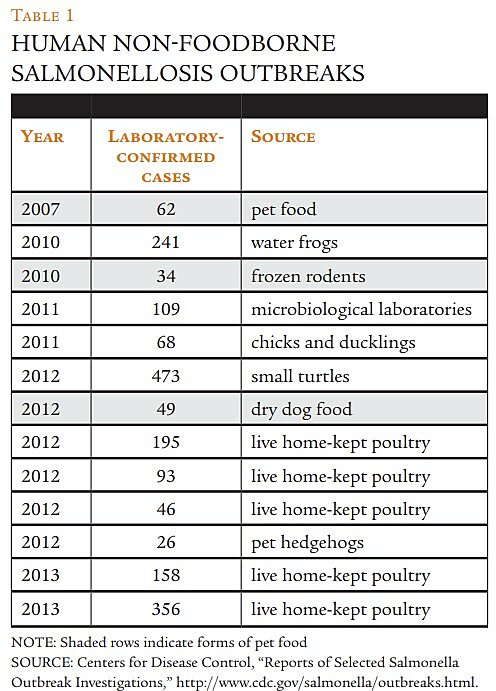

Another significant portion of reported hazards consists of salmonella present in animal food. The largest number of animal food hazards submitted to the Reportable Food Registry between 2009 and 2011 involved salmonella, which accounts for 21 of the 47 reports in those years. Between 2006 and 2010, salmonella led to the second-highest number of pet food recalls after melamine, accounting for 17 percent of all Class I pet food recalls. The RIA reports that in most cases, human infection occurred because of improper handling (hand-to-mouth contact) of contaminated dry pet food or frozen mice intended as reptile food.

The real culprit here is not the absence of regulation, but rather improper handling of animal food by consumers. In its report on a major salmonella incident linked to pet food, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) noted,

To prevent Salmonella infections, persons should wash their hands for at least 20 seconds with warm water and soap immediately after handling dry pet foods, pet treats, and pet supplements, and especially before preparing and eating food for humans. Infants should be kept away from pet feeding areas. Children younger than 5 years old should not be allowed to touch or eat dry pet food, treats, or supplements.

The FDA should at least have assessed whether a much less restrictive approach, such as a parental education campaign or mandatory warning labels containing the CDC’s advice, could effectively reduce salmonella-related illnesses.

Where Are the Benefits?

The FDA usually estimates benefits for its regulations by first estimating the maximum total number of cases of illness associated with the products covered by the regulation. Then it translates that number of illnesses into monetary terms. Finally, it multiplies that maximum monetary amount by its estimate of the effectiveness of the regulation at preventing illness.

The FDA stated that it does not have enough information to estimate the benefits of the proposed regulation. The necessary information for such an estimate includes the number of cases of human and animal illness associated with animal food that the regulation would prevent and the value of those cases of illness. Estimating the total number of cases and, in some instances, the effectiveness of various options at reducing those cases is a risk assessment. Yet, the FDA chose not to perform a quantitative risk assessment for this rule.

Data do exist to make some reasonable estimates of the maximum total number of illnesses associated with animal food and the monetary value of those illnesses. However, those data do not appear to justify the FDA’s regulatory conclusions.

In the RIA, the FDA named four potential benefits of the regulation:

- reduced risk of adverse health effects to humans from handling contaminated animal food

- reduced risk of serious illness and death to animals

- reduced risk of humans consuming food derived from animals that consumed contaminated food

- reduced risk of product recalls

We address those risks below.

Reduced risk to humans / In the RIA, the FDA states, “Salmonella, the most commonly identified biological hazard in animal foods, primarily affects humans that handle contaminated animal food.” Data from the CDC allow us to estimate the maximum possible number of those cases that may be due to animal food.

The CDC estimates that there are just over 1 million human cases of salmonellosis in the United States every year associated with domestic food consumption. Some 94 percent of those cases are related to human food consumption. Therefore, using CDC data, we can calculate that there are roughly 65,500 human cases of salmonellosis in the United States every year that are not travel-related and are not related to human-food consumption.