No task in government is as Sisyphean as trying to stop bad regulatory ideas from becoming law. For three and a half years, that was Cass Sunstein’s job as administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (the branch of the Office of Management and Budget tasked with reviewing the regulatory activities of executive agencies). He discovered early on that being the regulatory cop for the White House puts one in the cross-hairs of every single administrative agency seeking to have its regulations approved.

Sunstein was a renowned legal scholar at the University of Chicago (and a friend of Barack Obama) before entering government, and last year decamped to Harvard. He recently authored the book Simpler: The Future of Government (Simon and Shuster), which rationalizes his attempt to implement retrospective regulatory review while waxing philosophical about a better approach to government.

His tenure at OIRA was, from a limited government perspective, as good as anyone could have dared hope from an Obama administration that includes many regulatory mandarins deeply skeptical of the very notion of benefit-cost analysis (BCA). Sunstein may not be a professional economist, but he is sincere in wanting a smarter—if not leaner—government.

Still, as he concedes, in the last four years the federal government has imposed new regulations costing the public billions of dollars. The OMB itself estimates the annual compliance costs for regulations issued in the last decade to be between $57 and $84 billion. Those eye-popping numbers almost surely represent an underestimate of the actual impact of the encroaching regulatory state: the 2013 Draft Report to Congress on the Costs and Benefits of Government Regulations reports that fiscal year 2012 was the highest-cost year for new regulations ever, and it reached that conclusion after analyzing only 14 regulations of the 3,800 adopted.

Analyzing the regulators | Can we be sure that the benefits to society from these regulations are worth the costs? Determining that is precisely the job description for OIRA. However, when the entities that propose the regulations are also the ones that provide OIRA with benefit-cost information, OIRA’s task can become a bit complicated. It requires a mixture of political acumen and sheer chutzpah to tell the Environmental Protection Agency “no,” especially in a Democratic administration.

Should we thank Sunstein for making things better than they could have been, or did various political exigencies manage to roll over him, leaving us with an unnecessarily costly regulatory environment? If we merely critique the original benefit-cost analyses the various agencies used to justify their proposed rules, we will add little to the debate. We can do more.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Michael Greenstone noted that most regulations are subject to cost-benefit analysis only before being implemented, when any analysis depends on a variety of assumptions and forecasts of the future. While projecting costs and benefits into the future may be difficult, it ought to be straightforward to look at recently issued regulations and determine whether the resulting costs and benefits resemble those estimated by the various agencies in the initial analysis. That information could then be used to fix or repeal regulations that fail a benefit-cost standard while also refining how we do prospective BCA for future regulations.

It is easy to understand why the agencies would resist doing such a thing. Agencies exist to regulate, and the last thing they want to see is their handiwork unwound or their hands tied in the future in some way.

It ought to be straightforward to look at recently issued regulations and determine whether the resulting costs and benefits resemble those estimated by the various agencies in the initial analysis.

In 2011 Sunstein introduced a highly trumpeted initiative to do an ex-post review of regulations, emphasizing “Regulatory Moneyball,” or valuing metrics over political exigencies. The effort, however, was nothing that Billy Beane would have recognized: the retrospective review focused on a handful of regulatory anecdotes while ignoring thousands of other regulations that truly merited a serious ex-post analysis, such as including independent agencies that are currently exempted from OIRA’s requirements.

Opponents of thorough retrospective review should welcome the opportunity to prove their regulations return net benefits. For example, shouldn’t progressives want to know that rules designed to reduce pollution actually achieve results, or that companies have found ways to implement the measures without exorbitant costs?

That would be the ideal retrospective scenario, at least for all “economically significant” regulations, but the White House is not practicing anything like that. Instead, it has borrowed heavily from the previous administration to claim “retrospective” synergies from simple command-and-control regulations.

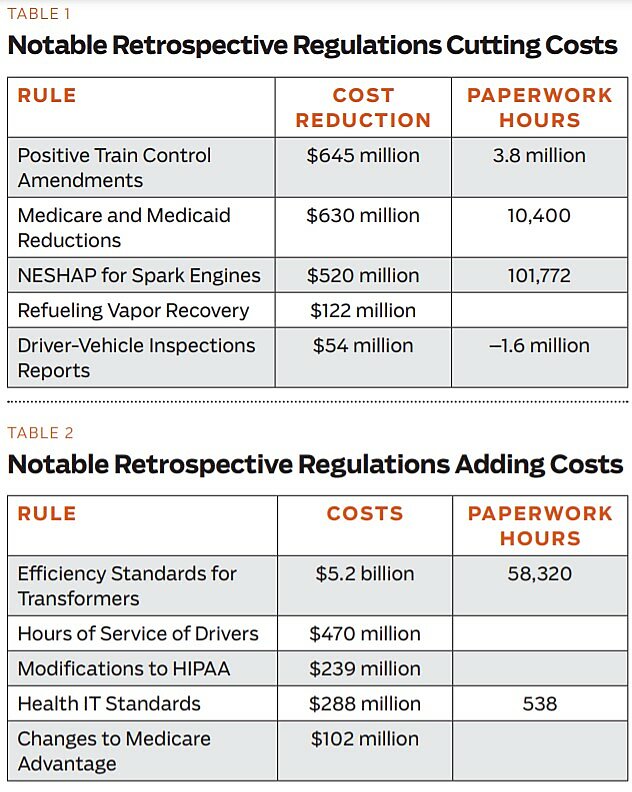

A thorough examination of various retrospective reviews suggests that the government rarely reviews existing regulations to lessen burdens. Over the last three years, retrospective review has yielded potential compliance cost savings of $3.3 billion, most of which stems from minor Medicare and Medicaid reforms and tweaks to the “Positive Train Control” rule on railway safety. The total paperwork savings from this exercise was 11.7 million hours, or one-tenth of 1 percent of total regulatory paperwork. Some notable regulatory cost reductions from this effort are shown in Table 1.

However, the savings from this retrospective review pales in comparison to the myriad rules that the administration actually implemented under the auspices of the order. Some of those rules are shown in Table 2. Once all “retrospective review” regulations are included, costs and paperwork hours added an additional $11 billion in compliance costs and 5.3 billion paperwork burden hours—which is not exactly how retrospective review is meant to function.

Other countries, most notably South Korea, have done an admirable job reviewing and reforming their regulatory state. South Korea has already reviewed more than 11,000 regulations, eliminating 50 percent of them while reforming an additional 2,400. Compared to the mere 90 rulemakings our “Regulatory Moneyball” examined, it is clear we have plenty of room to try to improve.

State governments are doing better on retrospective review. In 2012, then–Indiana governor Mitch Daniels signed legislation that codified several retrospective review principles. Three years after a regulation becomes effective in Indiana, the state’s Office of Management and Budget submits a second BCA, comparing the regulation’s actual effect on “consumer protection, worker safety, the environment, and business competitiveness” to the original estimate. The legislation did not elicit much opposition from either Democratic legislators or the populace.

Justice Louis Brandeis once commented that there is no great writing, only great rewriting. Our regulatory analysis lacks rewriting: once government implements a rule, no one pays any heed to how well—or whether—it is working and it is scarcely thought of again, except by those who must devote resources to comply. Our regulatory apparatus needs to acknowledge that we may not get it right the first time. We need to force the government regulatory bureaucracy to re-examine regulations and make an attempt to improve them whenever possible.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.