The percentage of American workers currently covered by “defined contribution” (DC) retirement plans like 401(k)s is far higher than the percentage that has ever been covered by traditional “defined benefit” pension plans. In the United States, DC plan assets totaled $8.9 trillion as of September 30, 2022, according to Investment Company Institute data, and over two-thirds of that money was in private-sector 401(k) plans. In addition, much of the estimated $11.0 trillion of IRA assets as of that date was from 401(k) rollovers.

In retirement, the default way to make use of DC plan accounts is to withdraw funds (“decumulation”) as needed or desired. This process risks participants running out of money before death or, on the flip side, spending less than was possible and not enjoying retirement to the fullest.

Surveys of employers and employees indicate interest in having options to generate lifetime income (to supplement Social Security benefits) from DC plan accounts. Congress has only recently started attempting to facilitate the conversion of DC plan balances into lifetime income. Under the influence of industry lobbying, Congress effectively endorsed the use of insurance products like annuities to provide such income in provisions of the 2019 SECURE Act. “Secure 2.0,” which was part of the $1.7 trillion Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, further facilitates the use of insured products for retirement plans, primarily by relaxing aspects of the rules around required minimum distributions.

However, by addressing insured products only, Congress has implicitly, even if unintentionally, skewed the market to disfavor other approaches that would work better for many. Tontines are one such alternative. They are well-regarded noninsured financial arrangements that can be used to generate lifetime income from pots of money. They have proved successful in the United States and elsewhere. Unfortunately, they are likely not permissible for use by private-sector DC retirement plans. Congress would do well to consider retirement policy broadly to allow and facilitate the use of tontines, and possibly other non-insured arrangements, for converting private-sector DC plan accounts into lifetime income.

How tontines work / Tontines are uninsured longevity-pooled accounts that can be used to provide retirement income certain to last a lifetime. They are always fully funded and require no capital reserves.

When a member of the longevity pool dies, her remaining account is distributed among the surviving members. To illustrate this process, consider a pool of a thousand 65-year-old female retirees. If each contributes $100,000 to the pool (for a total starting fund of $100 million) and, in the following year, the fund earns 5 percent and seven pool members die, then the balance in each survivor’s account at the end of the year is $105,740 ($100 million × 1.05 ÷ 993). In essence, the investment return of $5,000 is supplemented by a “longevity credit” (additional return) of $740 from the redistribution of the deceased members’ assets.

A popular conception of tontines, perhaps inspired by episodes of the TV series The Simpsons and Diagnosis Murder and literary works like Agatha Christie’s 4.50 from Paddington, involves payments growing significantly over time to survivors or a winner-take-all payment for the last survivor. While tontines can be structured to provide such a back-loaded payout pattern, another use of tontine pooling is to create a stream of payments that lasts for life.

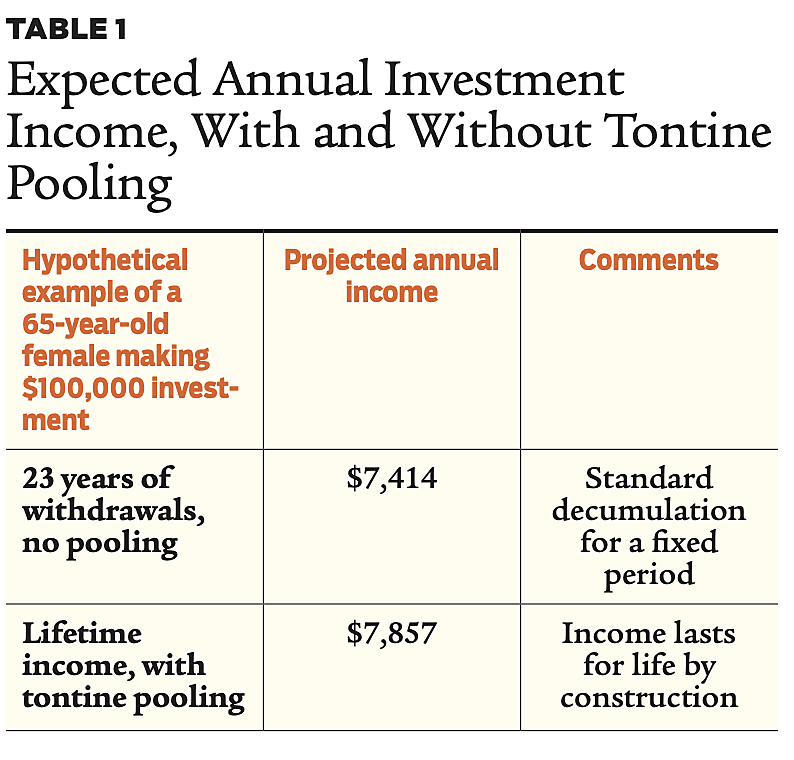

Absent pooling, a simple approach for a 65-year-old retiree to generate income from a $100,000 investment would be to calculate the annual income that could be supported over her life expectancy of approximately 23 years, assuming an expected 5 percent annual investment return. At the end of each year, payments for the remaining years can be recalculated based on the actual return that year and the resulting account balance. The initial expected annual income for 23 years in this example would be $7,414 per year. The math is the same as that used to calculate a mortgage payment.

But the retiree has a good chance of living more than 23 years and the investment fund would be depleted in 23 years. (If she dies during the 23 years, the remaining fund goes to her heirs.) For some people, the risk of outliving one’s retirement savings, or lowering the annual payments along the way to make them last, is unacceptable.

One way to make income last for life would be to buy an annuity from an insurance company, which is what Congress endorsed in SECURE and Secure 2.0. Another way is to join a tontine that pools longevity and uses the remaining accounts of pool members who die to provide income to survivors.

Doing the same mortgage-type calculation described above to the end of the assumed mortality table, except making each payment conditional on surviving to the time of payment, results in $7,857 of annual income for life, 6 percent more than the $7,414 without pooling that can be provided for 23 years only. The incremental income in terms of both annual amount and potential duration of payments is from longevity credits, i.e., the money left over from people who die, plus subsequent earnings thereon, allocated to the pool of survivors.

Table 1 summarizes the expected annual income for a group of pooled 65-year-old females, with an approximate life expectancy of 23 years, each investing $100,000 and reasonably expecting to earn 5 percent annually.

In a tontine providing lifetime income, the annual amount would be recalibrated each year to reflect the difference between the actual and assumed investment and mortality experience during the prior year and (possibly) changes in forward expectations.

Tontine pooling can be used to generate different payment patterns, such as benefits continuing until the possibly later death of a spouse. Longevity pools need not be uniform in terms of age and/or gender. Open pools with new entrants that exist indefinitely are possible. Tontine longevity pooling could even be applied among people with different underlying investments, allowing each person in a longevity pool to express a personal investment risk/return preference.

Tontines vs. insured annuities / Insured income annuities pool longevity similarly to a tontine providing lifetime income. But there are important differences, and many of them support the use of tontines.

One major difference is what happens when mortality or investment returns differ from expectations. For example, if people in the longevity pool live longer than anticipated or investment returns fall short of expectations, insurance companies generally absorb those losses, and—conversely—benefit from the gains if experience is in the other direction. In a tontine providing retirement income, there are no such guarantees, and pool participants absorb variations in experience, good or bad, through adjustments to their income. Existing tontines often embrace a modicum of investment risk in the hope that income will increase over time.

The guarantees provided by insured annuities are expensive. Capital reserves must be maintained to back them. Non-mutual insurance companies have shareholders demanding profits. Insurance companies can have significant overhead. Depending on the product, hedging programs and complicated financial engineering may be involved. All else equal, in forgoing the guarantees provided by insurance contracts, tontines should provide higher lifetime income on average through the reduction of expenses.

Another difference between tontines and annuities is the latter’s default risk. Discussions of the pros and cons of insured products rarely consider the risk that even highly rated insurers will be unable to make good on their guarantees. This implicit absolute faith in insurers may be overly presumptuous.

In the low interest rate environment of recent years, the insurance industry underwent a restructuring in a search for yield to fund their promises. Nontraditional (and risky) investments, the offloading of policy guarantees to offshore reinsurers to take advantage of more lenient regulatory regimes, and more complex forms of insurance company ownership structures and affiliations (often involving private equity firms) have almost surely increased policyholder risk. Because these developments are relatively recent, it remains to be seen how the industry and specific companies will fare in a challenging economic environment. State guarantee funds provide some protection to policyholders for insurer default, but it is limited.

Retirees receiving lifetime income associated with a 401(k) plan who suffer a loss from an insurer defaulting are unlikely to be successful holding the plan sponsor accountable, which is as Congress intended in SECURE. Tontines, being mutual pools without external guarantors, are not subject to default risk.

Existing tontines / In the United States, CREF (the College Retirement Equities Fund) is a $200+ billion multiple employer DC plan serving colleges, universities, research organizations, and other nonprofits. It was created in 1952 by the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAA), an insurance company providing traditional insured annuities to the same groups, to give participants opportunities for higher retirement income associated with investing in riskier assets in exchange for bearing the market risk. Both TIAA and CREF are effectively nonprofits.

CREF’s product is called a “variable annuity” (not to be confused with retail products with that name), but it is effectively a tontine. CREF longevity pools are open, with new entrants being added continuously. Participants can select and even change investments during retirement, although they cannot change the form of benefit once started; this prohibition is needed for fair longevity pooling.

There are also retirement plans sponsored by U.S. national umbrella church organizations that provide lifetime income through tontine-like pooling under Section 403(b)(9) of the Internal Revenue Code. However, these arrangements are not permissible in 401(k) plans.

Tontines are gaining traction in other countries. For example:

- The Longevity Pension Fund offered by Purpose Financial in Canada is essentially a tontine in the form of a mutual fund that launched in 2021.

- The University of British Columbia (UBC) Variable Payment Life Annuity (VPLA) is like CREF, on which it was modeled. Canadian income tax regulations were issued in June 2021 to facilitate the further development of VPLAs more broadly.

- In Australia, at least one of the “superannuation” funds that manage and administer mandatory retirement savings pools and accounts (as in a DC plan) launched a “LifeTime Pension” option. It is essentially an income tontine modeled on the UBC VPLA.

There is no reason from a retirement policy perspective that tontines should be permissible for church plans under IRC Section 403(b)(9)—as well as public sector plans not subject to most federal pension rules—but not for private-sector DC plans. There also is no reason from a technology perspective that tontines couldn’t be used in many other contexts within and across plans and plan sponsors.

Now that policymakers are focused on lifetime retirement income, it’s time for them to level the playing field and facilitate tontines having a place in the evolving U.S. DC-based private sector retirement system.

Readings

- “A Short History of Tontines,” by Kent McKeever. Fordham Journal of Corporate and Financial Law 15(2): 491–521 (2010).

- “Individual Tontine Accounts,” by R.K. Fullmer and M.J. Sabin. Working paper, 2021.

- King William’s Tontine, by Moshe A. Milevsky. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- “Tontine Pensions,” by Jonathan B. Forman and Michael J. Sabin. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 163(3): 755–831 (2015).

- “Tontines: A Practitioner’s Guide,” by Richard K. Fullmer. CFA Institute Research Foundation Brief, 2018.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.