Last December, at the urging of President Biden, Congress enacted legislation to stop a nationwide railroad workers’ strike. Negotiations between the freight railroads and their labor unions over the last three years had faltered over the unions’ insistence that any agreement include 15 days of paid sick leave. The contract imposed by the legislation gives workers a 24 percent wage increase and additional lump sum payments, but only one additional personal day.

President Biden’s support for government intervention in the labor dispute and imposition of a contract that, overall, can be considered to side with the railroads is interesting given that he professes to be a “pro-labor” president. He justified his decision by citing the potential economic consequences of a railroad strike, arguing in a statement:

As a proud pro-labor President, I am reluctant to override the ratification procedures and the views of those who voted against the agreement. But in this case—where the economic impact of a shutdown would hurt millions of other working people and families—I believe Congress must use its powers to adopt this deal.

It is likely that the Biden administration’s determination to side with management is a manifestation of a broader decline in union bargaining power. The existence and bargaining power of railroad unions are a legacy of the history of railroad regulation and labor relations. While certain aspects of the industry and the laws governing labor relations have helped rail unions maintain some of the highest private sector membership rates in the United States, since the deregulation of railroads in 1980, union membership has been waning. In the decades following deregulation, rail revenues soared and railroads were able to erode some of the unions’ work rules.

Recent declines in railroad revenues have provided more incentive for railroads to cut labor costs, but the existing union work rules have constrained the ways in which railroads can do so. Ultimately, railroads have elected to reduce total employees, increasing the burden on those who remain.

How did this come about? The root cause of the railroads–labor fight is the highly competitive U.S. freight transport sector. As that competition continues, railroads will seek further cost reduction by reducing their labor force and unions will push to protect jobs and increase workers’ pay.

History of Rail Regulation

Federal regulation of railroads began with the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) in 1887. The impetus was pressure from farmers and shippers in the western and southern United States who felt disadvantaged by railroads charging higher freight rates for short vs. long hauls and for small vs. large shippers. State regulations had proven ineffective in curtailing such practices, and in 1886 the Supreme Court ruled that states could not regulate interstate commerce. Congress thus established the ICC, tasked with ensuring that railroads charged reasonable rates and making sure they did not charge different rates for shipping the same commodity based on region or the length of the haul.

At first, the ICC was relatively weak, and was further weakened by Supreme Court rulings limiting its powers. But subsequent acts bolstered the agency through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The 1920 Transportation Act further expanded the ICC’s powers, giving it the ability to set minimum rates and control entry into and exit from rail routes.

Initially, ICC regulation and its constraint on intra-industry competition were welcomed by railroads. Rates set by the ICC helped stabilize profits and avoid price wars, making the ICC essentially a government-led cartel. The tradeoff for the railroads was that, once a line was established, they were only able to abandon it if given permission by the ICC, and approval to exit lines was often difficult to get. In practice, railroads were able to charge higher rates, which helped subsidize continued service on unprofitable lines. For the first 60 years of the ICC, when railroads transported a sizeable majority of interstate freight, this system worked in the railroads’ favor.

However, the regulations inhibited rail’s ability to respond to the growth of other modes of transportation, particularly the trucking industry, in the 1940s–1960s. The benefits of trucking in delivering high-value manufactured goods, spurred on by the development of the interstate highway system, created direct competition with railroads. The railroads attempted to remain competitive by reducing shipping rates but were often not allowed to do so by the ICC. And the barriers to exiting unprofitable lines hindered railroads’ ability to cut costs.

At the same time, railroads faced difficulties reducing labor costs because of large rail unions that derived much of their power from the Railroad Labor Act (RLA) of 1926. The RLA was negotiated by the railroads and labor unions as the final step in a series of railroad labor laws going back to the 1880s. Because of the violence associated with early railroad strikes and their disruption of commerce, the RLA and the preceding laws emphasize mediation of labor disputes and allow for government intervention to avoid strikes.

The RLA has some key differences from the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935, which governs labor relations in industries other than railroads (and airlines, which the RLA was extended to cover in 1936). First, the RLA requires that unions be based on class of employee (i.e., craft) and organized on a systemwide basis. The systemwide nature might make unions more difficult to organize initially because it requires 50 percent-plus-one support from all of a company’s workers in a particular craft, as opposed to unionization by individual location under the NLRA. But this also gives established unions systemwide bargaining power and makes it impossible to bust a union by simply closing one establishment.

Second, the RLA stresses maintaining the status quo. Union contracts never expire, and any amendments must be negotiated. Labor disputes must be adjudicated through an exhaustive mediation process, governed by the National Mediation Board and potentially with input from a Presidential Emergency Board. The process requires multiple “cooling-off periods” and both labor and management must maintain the status-quo while the mediation procedures unfold. The goal is to avoid disruptions, such as strikes, and through its history the act has been largely successful in doing so.

The effect of the RLA has been the creation of large, nationwide unions for different classes of rail employees. While unions in regulated industries typically benefit from the sharing of economic rents with companies, railroads’ inability to compete with alternative shipping modes meant there were few rents to be shared. Instead, economist James Peoples has argued that rail regulation created high labor costs by artificially increasing demand for labor through the requirement that railroads continue to service unprofitable low-density routes.

Throughout their history, railroad unions have maintained the high demand for labor and labor costs by opposing changes in railroad policies that would reduce the number of employees or their wages, even as technological change would allow for increased labor productivity or fewer employees. One prominent example of this is the locomotive fireman, whose job it was to shovel coal and tend to the fire on steam-powered locomotives. The emergence of diesel locomotives made firemen obsolete, but it wasn’t until the mid-1960s—30 years after diesel engines were first adopted and long after they were in widespread use—that a congressionally established binding arbitration board ruled that railroads were finally able to eliminate the fireman position.

Similarly, railroad employees were paid a day’s wage for every 100 miles traveled based on the daily range of a steam locomotive. The faster and more powerful diesel locomotives had greater range, which meant that 100-mile runs could be completed in shorter time. But unions refused to allow changes to the work rules and railroads were forced to continue stopping trains at 100-mile intervals for crew changes, slowing down service.

By the 1970s, as a result of the regulatory constraints on lowering shipping rates and abandoning unprofitable routes, worsened by limitations on their ability to cut labor costs, railroads were in a dire financial situation. Decades of low rates of return on investment in the industry and the bankruptcy of multiple Northeast railroads led to a wave of acts intended to relax regulations and sustain the rail industry.

First, the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973 consolidated the bankrupt Northeast railroads under federal control as the Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail), which was eventually sold back to private industry and broken up in the 1990s. Second, the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976 allowed the railroads more flexibility in setting rates. Finally, in 1980 the Staggers Rail Act partially deregulated the railroads as part of a broader trend toward surface transportation deregulation under the Carter administration. Before the Staggers Act, airlines (in 1978) and trucking (in 1980) also were deregulated.

Though the Staggers Act did not fully deregulate rail, it did allow for much greater freedom to set rates, negotiate prices with shippers, abandon unprofitable routes, and consolidate firms. This freedom allowed freight rail to become competitive once again and has been largely seen as a success.

The Effects of Deregulation

The Staggers Act had near immediate effects on the structure and productivity of the rail industry. The industry was already experiencing consolidation before the act, but it saw a sharp decline in the number of Class I railroads (railroads with revenues over an inflation-adjusted threshold, $900 million in 2023) after the act. There were 39 Class I railroads in 1980. By 2000, mergers had consolidated the industry to the seven Class I roads that remain today. Of those, the largest four are roughly divided into two duopolies, one in the western half of the United States with BNSF Railway (BNSF) and Union Pacific Railroad (UP), and one in the east with CSX Transportation (CSX) and Norfolk Southern Railway (NS). Those four railroads control a market share of around 90 percent. Three other Class I railroads, Grand Trunk Corporation (GTC, the U.S. subsidiary of Canadian National Railway), Soo Line Railroad (SOO, the U.S. subsidiary of Canadian Pacific Railway), and Kansas City Southern Railway (KCS), operate at the fringes.

Along with this consolidation, the ability to abandon unprofitable routes and the freedom to change shipping rates, as well as increased shipments of coal, chemical, and intermodal freight, helped produce a spike in productivity and profitability. Previously in Regulation, B. Kelly Eakin et al. explained that total factor productivity growth of railroads far outpaced growth in airlines, trucking, and other private businesses in the first three decades after the Staggers Act. This increased productivity translated to lower prices for shippers and financial stability for the railroads.

While deregulation was beneficial to railroads and shippers, the effect on labor has been more negative. The high pre-Staggers labor costs were passed on to customers through high shipping rates. But deregulation created more pressure for railroads to find ways to cut costs and has diminished some of the bargaining power of railroad unions. In the decades after deregulation, railroads were able to negotiate more favorable work rules, including an increase in the workday mileage from 100 miles to 108 miles and then to 130 miles, and the further reduction of unnecessary train crew members. While the fireman was eliminated in the 1960s, before the Staggers Act, union work rules still required four-person crews: a locomotive engineer, conductor, and two brakemen. Railroads were able to eliminate the brakemen and have found other ways to drastically reduce their total workforce.

Railroads also negotiated smaller wage increases in the post-Staggers period, which lowered workers’ real wages. Peoples and Wayne Talley estimate that union and non-union railroad employees experienced a decline in real wages between the pre- and post-deregulation periods (1973–1980 and 1981–2001, respectively). However, they find that, while the smallest decline was for railroad managers, union laborers generally had much smaller declines than non-union laborers. This suggests that, while unions experienced a decline in bargaining power, they remained powerful enough to avoid much of the decline in wages for non-union employees.

In fact, rail unions are some of the most powerful private sector unions in the country. Previously in Regulation, Michael Wachter described the rise and fall of unions in the United States. He noted that unions are largely a legacy of the corporatist New Deal regime and that their long decline since their peak in the 1950s has been a result of the dismantling of this regime through legal and political interventions, including deregulation of railroads, airlines, and trucking.

Compared to unions in other industries, however, rail unions remain relatively strong. As Table 1 indicates, union membership in rail, trucking, and airlines were high compared to other private industries before 1980. Whereas trucking and other industries saw a sharp decline in the 1980s and 1990s, rail and airline union membership (which are both governed by the RLA) remained at roughly 80 percent and 40 percent, respectively, into the 1990s. Today, union membership has decreased substantially but is still much higher for railroad employees at 54 percent, compared to 38 percent in the airline industry, 7 percent in trucking, and 10 percent in other private industries. Meanwhile, the railroad workforce sharply declined from 1973 to 2021, while the workforce in the other industries sharply increased. (Within some specific rail occupations, such as locomotive engineers, union membership rates remain even higher, at nearly 80 percent in 2021. But even in those occupations, both union membership rates and the total number of union employees have shrunk in the last four decades.)

Relative to other industries, rail unions likely benefited from the profitability and consolidation generated by deregulation, as well as their treatment by the RLA. First, in theory labor unions have more bargaining power in oligopolistic industries that have barriers to new entrants. Unlike the consolidation seen in the post-deregulation railroad industry, deregulation made trucking highly decentralized. Second, the decentralization and increased competition in the trucking industry led to decreased profitability for trucking firms. Meanwhile, rail profitability, driven by more shipments of coal, chemicals, and intermodal freight, increased. Finally, the RLA’s creation of nationwide bargaining units and emphasis on keeping the status quo may have allowed rail unions to hold onto more power, slowing their decline. In contrast, truckers’ unions, governed by the NLRA, are at the establishment level and were weakened by non-union competition.

The Current State of Freight Railroads

In the recent labor disputes, unions opposed a reduction in the total number of employees. They argued this has caused staffing shortages that increase the burden on the employees who remain and has meant that those employees have little scheduling flexibility. And unions complain that railroads offer limited paid sick leave.

The employee reductions are part of railroads’ general focus on cutting operating expenses, called precision scheduled railroading, which aims to streamline operations and decrease the amount that railroads spend to earn the same amount of revenue. This is achieved in a variety of ways beyond just reducing labor costs, including increasing the number of railcars per train, improving fuel efficiency, and changing delivery methods to increase the speed of delivery.

Of course, unions dislike reduced employment. They argue that railroads earn huge profits but refuse to share that money with workers and give them acceptable work–life balance. For example, amidst the recent dispute, Liz Shuler, president of the AFL-CIO, said on Twitter, “Railroads are making their highest-ever profits & doing it on the backs of workers.” After Congress passed the legislation avoiding the rail strike, Sen. Bernie Sanders (D, VT) echoed Shuler in a press release:

Let me be clear. This struggle is not over. At a time of record-breaking profits for the rail industry, it is disgraceful that railroad workers do not have a single day of paid sick leave. As a member of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, I will do everything I can to make sure that rail workers in America are treated with dignity and respect.

Information on railroad operating revenues and expenses is readily available. While railroads were largely deregulated by the Staggers Act, the Surface Transportation Board (STB), an independent federal agency established to replace the ICC in 1996, has residual limited rate setting authority. As a result, Class I railroads must submit detailed reports to the STB every year. Compiling data from those reports allows us to assess freight rail companies’ economic conditions.

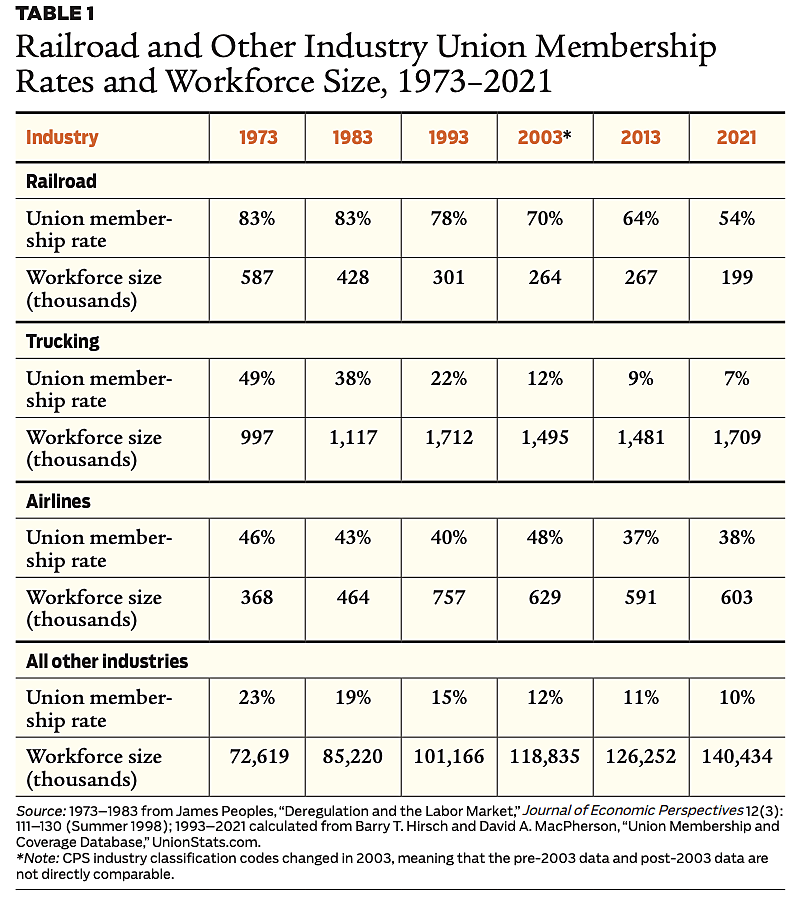

At first glance, the unions’ rhetoric would appear to be accurate. They claim that railroads have record high profits and, in fact, rail net operating incomes (meaning railroad operating revenue after deducting operating expenses and taxes) are currently high. Figure 1 shows inflation-adjusted income for the seven Class I railroads from 2013 to 2021. Four of the seven had their largest income level in 2021, and total Class I income was also at a decade high in 2021.

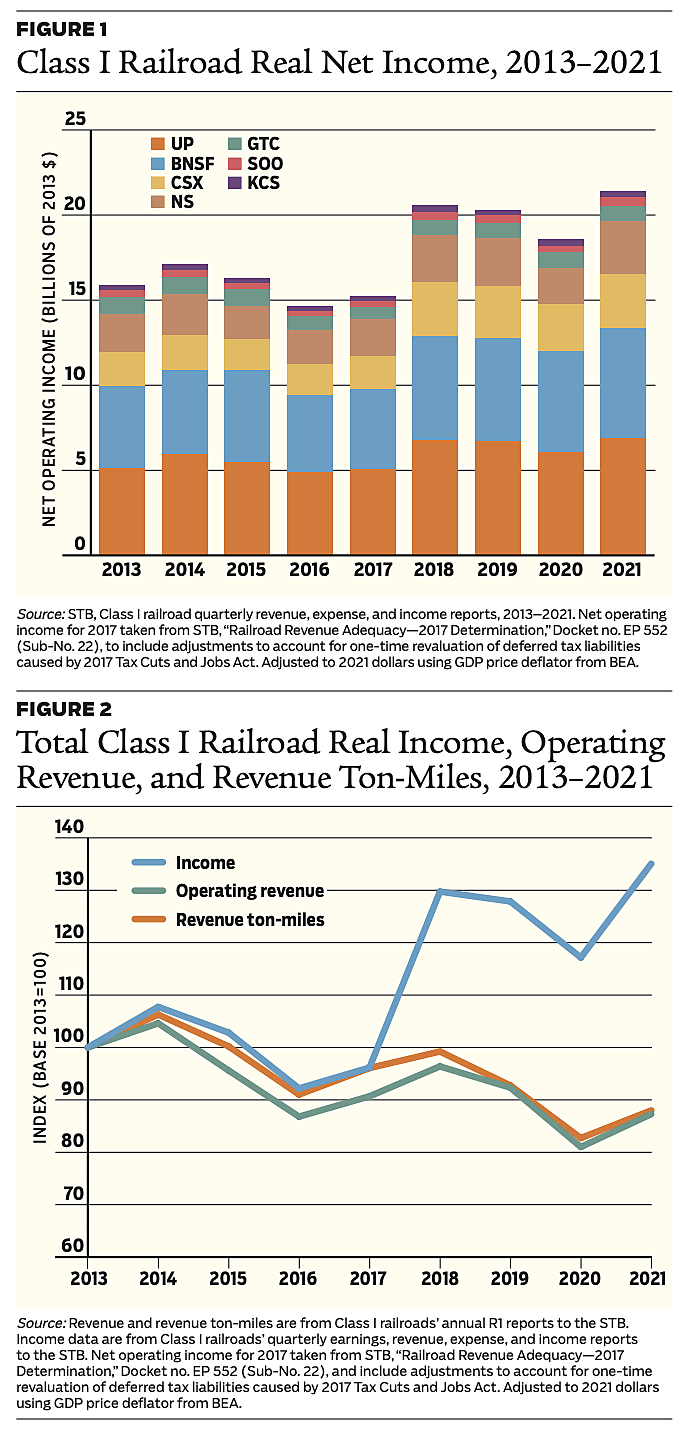

But the actual productive business of railroads is decreasing. Figure 2 shows total Class I real net operating income, real operating revenues, and revenue ton-miles (the total tons of revenue-earning freight multiplied by the total number of miles transported, a measure of rail volume) indexed to 2013. Whereas the three metrics generally trended together from 2013 to 2017, since then income has shot up while revenue and revenue ton-miles have declined. Profits for 2021 were 35 percent higher than in 2013, whereas revenue and revenue ton-miles were both down around 12–13 percent. From 2013 to 2021, real revenue per ton-mile remained nearly constant at around 4.7 cents per ton-mile, meaning that railroads are earning roughly the same amount per ton-mile but are transporting less freight and thus earning less total revenue.

The primary cause of the decreased revenue is a decline in one of the railroads’ most important businesses: transporting coal. Lower natural gas prices have reduced demand for coal. According to STB Commodity Revenue Stratification Reports, between 2010 and 2020, coal’s share of total revenue from all commodities fell from 23 percent to 9 percent and share of revenue ton-miles fell from 40 percent to 21 percent. In the meantime, some other types of shipments, such as intermodal shipping containers, have increased, but not enough to replace the lost revenue from coal.

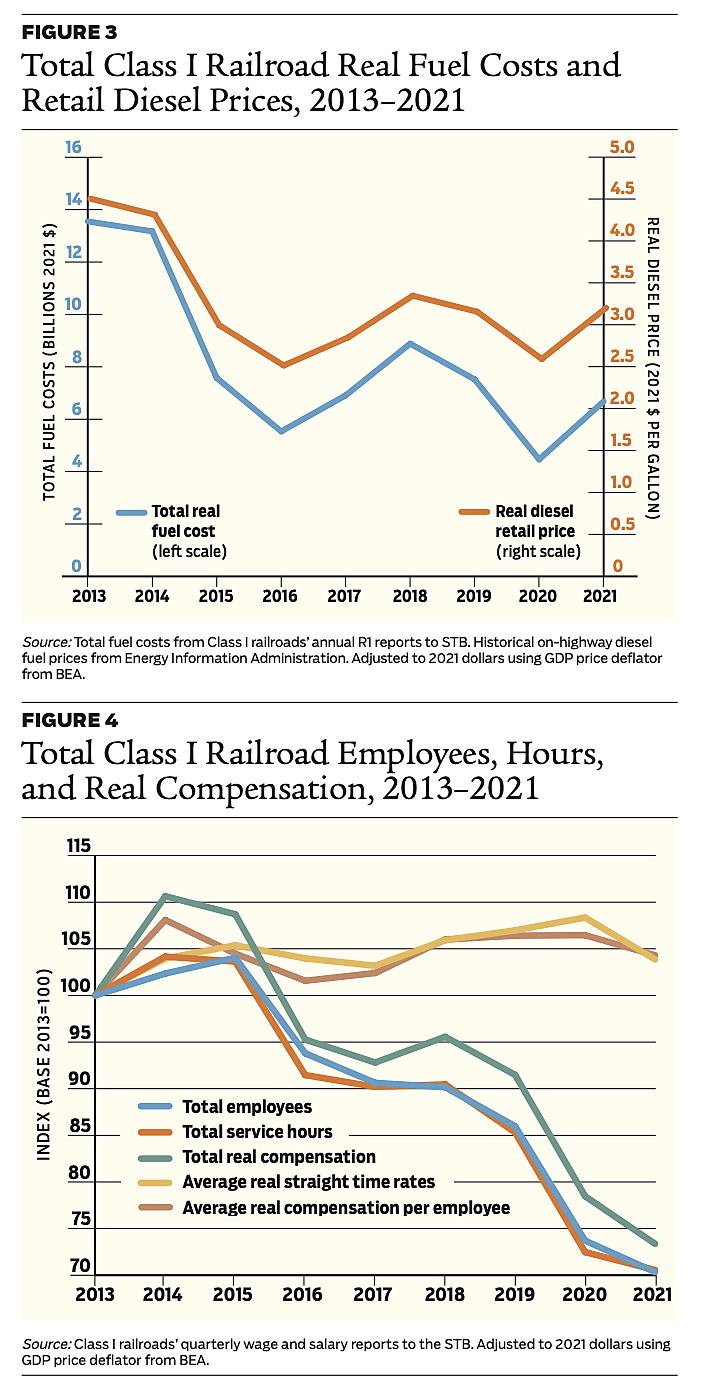

If revenue and revenue ton-miles are declining, how have profits increased? There are three primary sources of higher profits. First, fuel costs have been lower in recent years and dropped by nearly half between 2013 and 2021. This reduced cost is partially a result of fewer revenue ton-miles and better fuel efficiency (the average Class I railroad fuel efficiency was 476 revenue ton-miles per gallon in 2013 compared to 500 in 2021) but is mostly explained by lower diesel prices in general. Though the railroads pay less than the retail diesel fuel rate, Figure 3 shows that total Class I fuel costs have trended with the retail diesel price.

Second, profits increased steeply with the federal corporate tax rate cut from 36 percent to 21 percent enacted in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). Comparing averages of net revenue (i.e., operating revenues minus operating expenses before taxes are considered) and net income (i.e., after taxes have been deducted) shows the large effect. The average, inflation-adjusted total net revenue of the Class I railroads in the pre-TCJA period (2013–2017) was $25.3 billion, whereas it was $26.7 billion in the post-TCJA period (2017–2021). On the other hand, average yearly total net operating income pre-TCJA was $15.8 billion and post-TCJA was $20.2 billion. Thus, between the two periods, average yearly net revenue increased by roughly 6 percent while average net operating income increased by 28 percent.

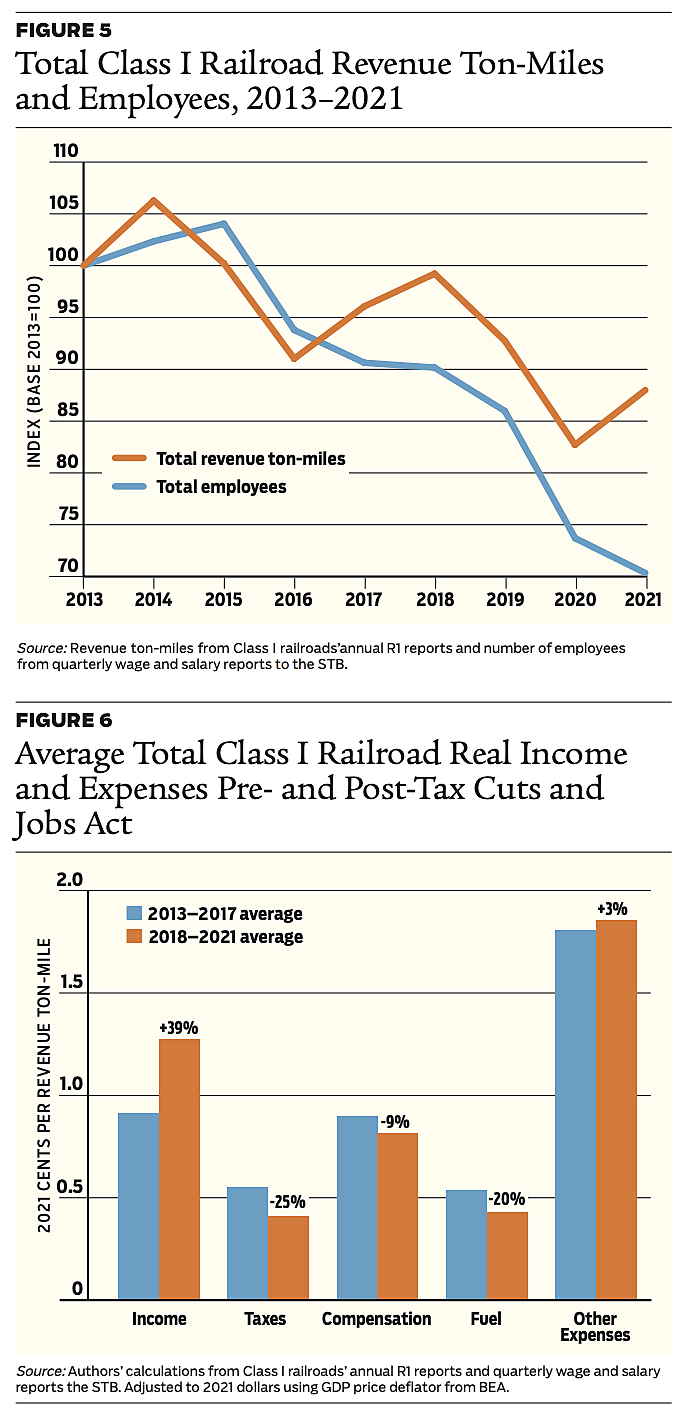

Finally, profits increased as railroads cut labor costs by reducing their workforce. As shown in Figure 4, the total number of employees, service hours, and real compensation have decreased by about 30 percent since 2013. However, during that time real average compensation per employee and average straight time pay rates (i.e., regular, non-overtime pay rates) have increased by about 4 percent.

The reduction in employment to some extent matches the decrease in revenue ton-miles, but employment has declined more than revenue ton-miles. Since 2013, revenue ton-miles fell by about 13 percent whereas the number of employees dropped by 30 percent. The difference is possibly explained by increased labor productivity from rail initiatives like precision scheduled railroading, allowing the railroads to achieve a higher amount of revenue ton-miles per employee. But in recent years the difference may also be largely caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and a lag in the response time between changes in revenue ton-miles and hiring. Figure 5 shows total Class I revenue ton-miles and employment from 2013 to 2021, indexed to 2013. During this period, declines in employment closely follow declines in revenue ton-miles. But when revenue ton-miles increase, the number of employees increases more slowly (as in the period 2013–2014) or remains flat (as in the period 2017–2018). Railroads’ employment response to short-term increases in revenue ton-miles is attenuated. Considering the longer-term decline in revenue in the past decade compounded by potential labor supply shortages caused by the pandemic and its aftermath, the railroads seem reluctant to increase employment to match the recent rebound in revenue ton-miles.

Relative to the first two factors (diesel costs and corporate taxes), the reduction in total compensation plays a minor role in increased profits. Comparing average total revenues per ton-mile in the pre-TCJA and post-TCJA periods illustrates how profits have increased as taxes, fuel costs, and labor costs have decreased. As shown in Figure 6, average real net operating income per revenue ton-mile increased by 39 percent between the two periods, while average taxes decreased by 25 percent, average fuel costs decreased by 20 percent, and average total compensation decreased by 9 percent.

Railroad profits are currently high because of lower fuel costs and taxes rather than increased business. The reduction in coal shipments, which seems permanent, has led to declining operating revenues. Large employment increases under such conditions are unlikely but there may be some increase to handle the intermodal shipments comeback after the COVID-19 pandemic.

From the perspective of unions, the railroad employee reductions are real and have led to staffing shortages. The burden of the shortages falls on the remaining employees, who would prefer more flexibility and scheduling certainty. But as we explain below, unions and their work rules contribute to the staffing shortages.

The Contribution of Unions to Lower Employment

The main function of labor unions is to increase wages for their members above competitive levels. This benefits current employees, but the higher wages typically come at the expense of consumers (if prices increase as a result) or potential new employees (because companies hire fewer workers).

Historically, when freight rail rates were set by the ICC, the high wages could be more easily passed on to consumers. Since deregulation, however, railroads have sought to reduce operating costs, including labor costs, to remain competitive. As union membership began to decline, railroads had some success in negotiating more favorable work rules, but the rules that remain still limit railroads’ ability to reduce labor costs commensurate with the recent downturn in revenue ton-miles.

For example, railroads’ ability to reduce wages is restricted. In the recent dispute, the Presidential Emergency Board’s recommendations, which were ultimately imposed by Congress, require railroads to increase wages between 2020 and 2024 by 24 percent and give employees an additional $5,000 in lump payments. This pay increase is more than multiple measures and projections of inflation over the period, meaning rail workers are getting a pay raise even though freight revenues have been decreasing in recent years. Furthermore, pay is still dictated by complicated trip and overtime rules and employees receive compensation for hundreds of hours each year during which they didn’t actually do any work.

Work rules also force railroads to continue dedicating resources to positions that are no longer necessary. Echoing the elimination of firemen in the 1960s and brakemen in the 1980s, railroads are looking to further reduce the size of train crews to one. Under their plan, trains would be operated only by locomotive engineers, while the role of conductors would become ground-based. They would be based at a central location to focus on off-loading and staging trains and would respond by truck when issues with trains on the rails arise.

Unions are fighting against this change and have urged the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) to require train crews of two. If the FRA adopts such a rule, it would be the first time that crew size has been set by regulation rather than collective bargaining. The unions argue that two-person crews are necessary from a safety standpoint, but the fact that both European freight railroads and Amtrak are operated by one-person crews suggests that there are neither freight- nor U.S.-specific safety or technological reasons why the rule is necessary.

These and other contract requirements mean that reducing the total number of employees is one of the few ways in which railroads can reduce labor costs. As long as the economic conditions justify cutting these costs and unions are unwilling to make concessions, railroads will likely continue to look at increasing the efficiency of a smaller pool of employees as one of their best options to reduce operating costs.

Conclusion

Since the breakdown in the most recent round of contract negotiations, railroad unions have reiterated their commitment to demanding more sick leave and scheduling flexibility in the round of negotiations scheduled for 2025. Meanwhile, railroad managers have suggested that they are planning to increase paid time off by revising existing scheduling systems or implementing new ones.

Considering that railroads were unwilling to acquiesce to union demands last year, the sudden about-face is puzzling. Perhaps railroads are concerned with how the tense labor negotiations affected their public perception or worker morale, or they have been motivated to make changes by activist investors. Or they may be anticipating the need to offer better working conditions for new and existing employees in light of the rebound in revenues and the tight labor market in the wake of COVID-19.

Whether the statements by managers will bear out or prove to be hollow promises, any decision by railroads to improve working conditions will likely be a response to their economic conditions, not the outcome of unions’ waning bargaining power.

Readings

- Deregulating Freight Transportation, by Paul Teske, Samuel Best, and Michael Mintrom. AEI Press, 1995.

- “Deregulation and the Labor Market,” by James Peoples. Journal of Economic Perspectives 12(3): 111–130 (Summer 1998).

- “Earnings Differentials of Railroad Managers and Labor,” by James Peoples and Wayne K. Talley. In Railroad Economics, edited by Scott M. Dennis and Wayne K. Talley, Elsevier, 2007.

- “More than Just Running on Time,” by Ike Brannon and Michael F. Gorman. Regulation 44(1): 20–23 (Spring 2021).

- “Railroad Deregulation and Union Labor Earnings,” by Wayne K. Talley and Ann V. Schwarz-Miller. In Regulatory Reform and Labor Markets, edited by James Peoples, Springer Science + Business Media, 1998.

- “Railroad Performance Under the Staggers Act,” by B. Kelly Eakin, A. Thomas Bozzo, Mark E. Meitzen, and Philip E. Schoech. Regulation 33(4): 32–38 (Winter 2010–2011).

- Railroads, Freight, and Public Policy, by Theodore E. Keeler. Brookings Institution, 1983.

- The Economic Effects of Surface Freight Deregulation, by Clifford Winston, Thomas M. Corsi, Curtis M. Grimm, and Carol A. Evans. Brookings Institution, 1990.

- “The Rise and Decline of Unions,” by Michael Wachter. Regulation 30(2): 23–29 (Summer 2007).

- “The Staggers Act, 30 Years Later,” by Douglas W. Caves, Laurits R. Christensen, and Joseph A. Swanson. Regulation 33(4): 28–31 (Winter 2010–2011).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.