News stories abound of kind people—relatives, close friends, and even complete strangers—who donate a kidney to someone suffering from kidney failure. These stories usually explain that people whose kidneys have failed must either obtain a transplant, which enables them to live 10–20 years in reasonably good health, or suffer on dialysis for an average of four to five years as their health steadily deteriorates until they die.

Sometimes these stories explain that many kidney failure patients never receive the optimal treatment of a transplant because there is a drastic shortage of transplant kidneys. About 125,000 patients are diagnosed with kidney failure each year, but only about 22,000 receive a transplant. In a 2022 Value in Health article, we estimate that more than 40,000 additional kidney failure patients would be saved from premature death each year if they received kidney transplants.

Recently, there have been news stories about xenotransplantation: the transplanting of animal organs (usually from pigs) into humans. These came after a patient with terminal heart failure received a genetically modified pig heart and lived for two months. That raised the hopes of many that this breakthrough might be extended to kidneys. However, Food and Drug Administration approval for xenotransplant kidneys will not occur for some time (if ever); the data from the first Stage One trial—which is merely the first step toward any approval—won’t be available for at least a decade. It is extremely unlikely that anyone currently suffering from kidney failure will benefit from xenotransplantation.

Few if any of these news stories lamenting the kidney shortage or touting high-tech breakthroughs mention that we already have a solution to the shortage: compensating kidney donors to induce more supply. Frustratingly, the U.S. government is obstructing this solution.

NOTA is the problem / Virtually all economists who have studied the issue believe the basic cause of the kidney shortage is a provision in the 1984 National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA): “It shall be unlawful for any person to knowingly acquire, receive, or otherwise transfer any human organ for valuable consideration for use in human transplantation if the transfer affects interstate commerce.”

This sentence seems innocuous, but it imposes a price ceiling of near-zero on the market for kidneys. Both economic theory and abundant evidence have shown that whenever the government holds the price of a good below the market-clearing price, it causes a shortage of that good. Moreover, if the government holds the price far below the market-clearing price (our 2022 article estimates that price would be about $80,000 per kidney), then the shortage will be huge: more than 40,000 kidneys per year in the United States alone. For context, that is more deaths than from motor vehicle crashes each year.

Compensation is the solution / To economists, the solution is straight-forward: allow kidney donors to be compensated. But this is not at all obvious to most non-economists, who fear it would lead to a world in which rich people would buy kidneys from poor people. Steven Levitt, co-author of the best-selling economics book Freakonomics, put the dichotomy this way in a May 2022 episode of his People I (Mostly) Admire podcast: “This is an interesting issue because it is one every economist agrees that of course we should have a market for kidneys, and virtually every non-economist thinks it is crazy.”

Because there are a lot more non-economists than economists, that takes the policy option of a completely free market in kidneys off the table. Instead, policymakers must come up with some solution that allows kidney donors to be compensated but addresses the concerns of the public through regulation.

There does seem to be a consensus developing that the government should take on the role of compensating kidney donors, and it should distribute the acquired kidneys to all patients who need one. In a 2018 PLOS One article, we showed that poor people as a group would be much better off if donors are compensated than they are now when compensation is prohibited, mainly because many would-be kidney recipients are poor.

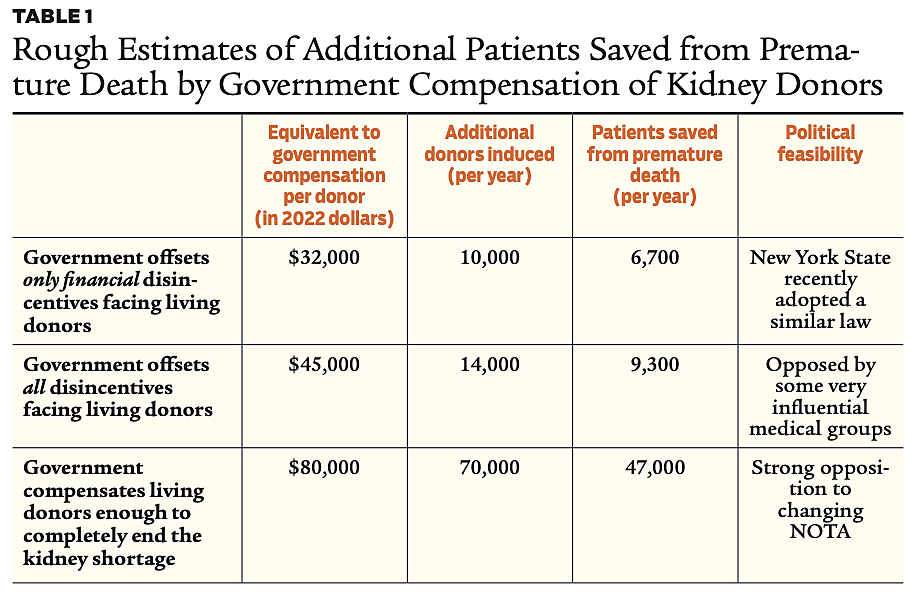

The tradeoff between the level of compensation and political feasibility / A crucial question remains: what level of compensation should the government offer to kidney donors? The answer is a political judgment call that involves the tradeoff between the number of patients saved from premature death and the probability of getting a particular law or regulation changed.

At the present time, the government offers virtually no compensation to kidney donors, just modest amounts for government employees and small amounts for some low-income donors and recipients through the National Living Donor Assistance Center (NLDAC). Consequently, there are only about 6,000 living donors each year. When added to the 16,000 kidneys from deceased donors, that is enough to save about 15,000 kidney failure patients per year from premature death (because the average kidney failure patient requires about 1.5 transplant kidneys to reach age 75).

Consider three alternative policies:

- Suppose the government decides to offset all disincentives to kidney donation, most notably the cost of travel and lodging near the hospital, the loss of income, and the cost of providing care for dependents. Donors also endure other costs of donating, such as the small risk of dying during kidney removal, the pain and discomfort of the procedure, the slight chance that the procedure will decrease the donor’s long-term quality of life, and concern that a relative or friend may need a kidney in the future and the donor will no longer have an organ to spare. In a 2019 Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, we estimate that removing all these disincentives would be equivalent to compensating donors about $45,000 (in 2022 dollars) per kidney. Providing this compensation to kidney donors would induce about 14,000 additional living donors annually, which would be enough to save an additional 9,300 kidney failure patients from premature death each year. (See Table 1, row 2.)

- However, some very influential members of the medical community oppose the government removing what they call “non-financial” disincentives to donating. If the government were to instead cover only the financial costs, we estimate that would be equivalent to the government providing about $32,000 in compensation per kidney. That would result in about 10,000 additional living donors, which would save an additional 6,700 kidney failure patients each year from premature death. (See Table 1, row 1.) New York State recently passed a law that would have the state do precisely that for living donors.

- In contrast, the government could do more than just cover donors’ pecuniary and nonpecuniary expenses. It could offer compensation to donors that would be high enough to completely end the kidney shortage. In our Value in Health article, we estimate that if the government offered living kidney donors about $80,000 per donor, it would be sufficient to induce about 70,000 additional donations from living donors, which would save about 47,000 people from premature death each year. (See Table 1, row 3.) However, this seemingly would violate NOTA and would arouse the strenuous opposition of those who are opposed to compensating donors for anything but narrowly defined expenses.

Organs from the deceased / Our discussion focuses on increasing the number of living, rather than deceased, kidney donors because the supply of kidneys from deceased donors is quite limited. Less than 2 percent of people die in a manner that allows the recovery of their organs for transplant. The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), which oversees the supply of transplant organs from deceased donors in the United States, claims it recovers the kidneys in 75 percent of those cases, for a total of about 16,000 kidneys per year. (Some critics of UNOS suggest it should be able to boost its recovery rate, but even if it recovered 100 percent of potential deceased-donor kidneys, that would still leave us far short of the 70,000 needed to completely end the kidney shortage.)

Compensating the families of deceased donors (which is also not allowed under NOTA) would not be enough to end the shortage, but it would boost the recovery of other major organs, such as hearts and lungs, that can only be obtained from deceased donors. The level of compensation needed to substantially boost the supply of cadaveric donor organs would presumably be much less than the $80,000 needed to obtain enough living donor kidneys. (See “Paying for Bodies, But Not for Organs,” Winter 2006–2007.)

Conclusion / The basic cause of the kidney shortage is the prohibition on compensating kidney donors. The solution is to find some way to compensate kidney donors that is acceptable to the transplant community and the general public. A consensus is developing that the government should compensate kidney donors and fairly distribute the resulting kidneys to patients who need one. But what level of compensation should the government offer?

There appears to be a tradeoff between the level of compensation and the amount of political opposition it will encounter. The higher the level of compensation, the more opposition it will face. That being the case, it would probably be best to start with just offsetting the financial disincentives facing kidney donors, as New York State recently did. Once the positive results of compensating donors are clear, that could provide the impetus for offsetting all disincentives facing living kidney donors. Further success could then open the way for providing compensation high enough to completely end the kidney shortage, which would save more than 40,000 people a year from premature death.

Readings

- “Financial Neutrality in Organ Donation,” by A.M. Capron, F.L. Delmonico, and G.M. Danovitch. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 31(1): 229–230 (2020).

- “Ideas to Increase Transplant Organ Donation,” by I. Brannon, J. Morrison, S. Beyda, et al. Regulation 45(2): 34–39 (2022).

- “Projecting the Economic Impact of Compensating Living Kidney Donors in the United States: Cost–Benefit Analysis Demonstrates Substantial Patient and Societal Gains,” by F. McCormick, P.J. Held, G.M. Chertow, et al. Value in Health, June 9, 2022.

- “Removing Disincentives to Kidney Donation: A Quantitative Analysis,” by F. McCormick, P.J. Held, G.M. Chertow, et al. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 30(8): 1340–1357 (2019).

- “Would Government Compensation of Living Kidney Donors Exploit the Poor? An Empirical Analysis,” by P.J. Held, F. McCormick, G.M. Chertow, et al. PLOS One, November 28, 2018.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.