In 2019 the Boeing 737 Max aircraft suffered two catastrophic accidents that resulted in 346 fatalities. Those tragic events led the Federal Aviation Administration to ground the aircraft until the underlying cause of the crashes could be determined. As of this writing, the 737 Max remains grounded. Boeing is paying billions of dollars in compensation to the families of those who perished in the accidents and to its commercial airline customers who must let their 737 Max jets sit idle.

It is likely the FAA will make regulatory changes in light of the accidents. The compliance costs for those changes — which could be substantial — will add to the cost of the 737 Max accidents. While the ongoing investigation may indicate that changes are warranted, federal authorities are likely to reflexively overregulate air safety. That overregulation can increase transportation fatalities as compliance costs drive up airfares and cause consumers to substitute higher-risk highway travel for air travel.

The Air Safety Calculus

The 737 Max crashes have made for sensational headlines at a time when air fatalities among major commercial airlines have become exceedingly rare. The last fatal U.S. airline crash was a decade ago when Colgan Air Flight 3407 crashed near Buffalo, NY, killing all 49 passengers aboard and one person on the ground. This contrasts sharply with the 36,560 fatalities on the nation’s roadways in 2018 alone, the most recent year for which data are available.

To put those numbers in perspective, in an average week the number of U.S. traffic fatalities represents more than twice the number of lives lost in the two Boeing 737 Max crashes. Because individuals “control” the car they drive but not the commercial plane they fly, they may underestimate the risk of highway travel vis-à-vis air travel. Fear of flying may serve to further distort their risk assessments.

The mortality rate for air travel is 0.07 fatalities per billion passenger miles as compared to 7.28 fatalities per billion passenger miles for automobile travel. These statistics imply that it is over 100 times more hazardous to drive than fly on a per-mile basis.

Despite the possibility of a troubling breakdown in regulatory oversight, the empirical fact that the risk of dying in an automobile crash is many times greater than dying in a plane crash should temper calls for unbridled increases in air safety regulation that also raise airfares. An increase in airfares will divert some portion of the traveling public from the air to the highways in what economists call the cross-elastic effect of airfares on the demand for automobile travel.

Suppose, for example, that the cross-price elasticity of highway travel with respect to air travel is H–A = 0.2. This means that a 10% increase in airfares would result in a 2% (0.2 × 10%) increase in highway miles traveled. Hence, from a public policy perspective, it is possible for air travel to be “too safe” in the sense that lives saved in the air come at the cost of many more lives lost on the ground.

According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, there were 694 billion domestic passenger air-miles and 5,502.42 billion total passenger highway miles traveled in 2017. Table 1 shows the effect of a 10% airfare increase on passenger highway miles traveled for various H–A values. Consider H–A = 0.06. With a 10% increase in airfare, an estimated 33 billion additional passenger-miles would be driven. This would be expected to result in an increase in annual highway fatalities of 240, which represents almost 70% of the fatalities in the two 737 Max crashes in a single year. What this analysis suggests is that even relatively modest increases in airfares resulting from more stringent regulation can easily cost more lives on the ground than are saved in the air.

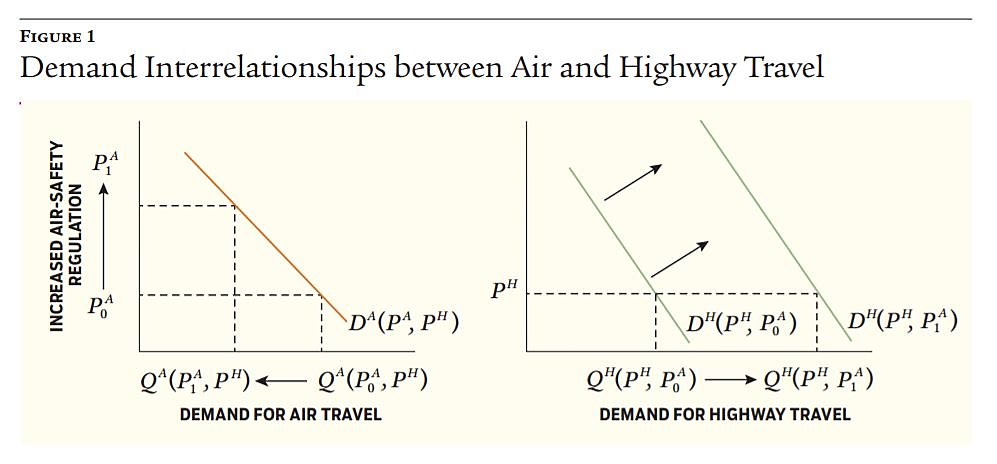

The effects of more stringent air safety regulation on the demand for air and highway travel are illustrated in Figure 1. Increased air safety regulation raises the price of air travel from P0A to P1A. (The analysis abstracts from the marginal shift outward of the demand curve for air travel that may result from safer air travel.) This reduces the quantity demanded of air travel from Q A (P0A , PH) to Q A (P1A , PH). Given that the two modes of travel are substitutes, the increase in the price of air travel shifts the demand curve for highway travel from D H (P H, P0A) to D H (P H, P1A) and causes an increase in the quantity demanded of highway travel from Q H (P H, P0A) to Q H (P H, P1A).

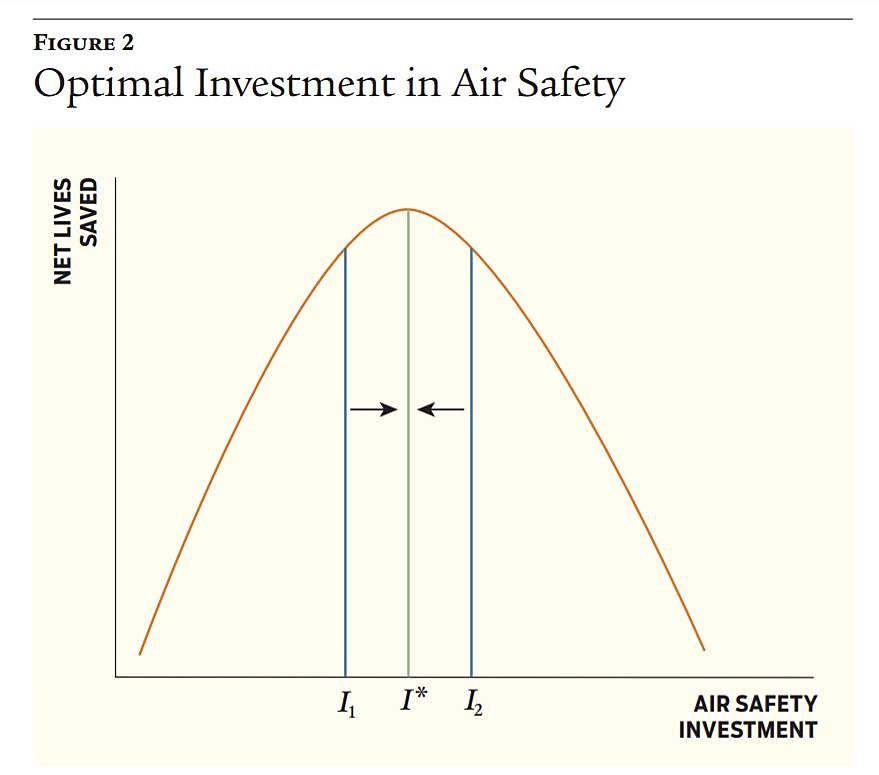

The FAA’s mission, according to its website, is to provide the safest, most efficient aerospace system in the world. If you ask economists about investment in airline safety, they will tell you that society’s optimal amount occurs when the marginal benefit of airline safety is equal to the marginal cost of airline safety. At that point, the last (marginal) dollar invested in airline safety confers a dollar in net benefits. For levels of investment less (greater) than that amount, the marginal benefit of an additional dollar invested in airline safety is greater (less) than the dollar that it costs.

It is important to understand precisely what this marginal condition says as well as what it does not. It does not say that society should invest in airline safety up to the point where the probability of an airline crash is effectively zero. The airline industry may well have the technology to achieve such an outcome, but that does not imply that society should commit to that level of investment. Because airline safety is subject to diminishing returns, achieving progressively lower probabilities of air accidents requires ever-increasing financial outlays. And airlines attempt to recover those expenditures through airfare price increases.

When the price of air travel rises, rational consumers will seek alternative modes of travel. This diverts some proportion of consumers from the skies to the highways, where their fatality probabilities are more than 100 times greater. The objective of increased travel safety transcends saving more lives in the air; it also should save more lives across all modes of travel. As a policy matter, we should not seek to save 10 more lives in the air if the cost is 1,000 more lives lost on the nation’s highways. The policy focus should be on net lives saved.

The stylized relationship between investment in airline safety and net lives saved is illustrated in Figure 2. At investment level I1, a marginal increase in investment in airline safety increases the number of lives saved in the air by an amount greater than the increase in the number of lives lost on the highways. This indicates that society would benefit from an increase in investment. The opposite scenario occurs at investment level I2, which indicates that society would benefit from a decrease in investment. The optimal amount of airline safety occurs at investment level I*. At this optimal level of investment, any marginal change in air-safety investment, positive or negative, reduces the net number of lives saved across both modes of travel.

Applications of the Air Safety Calculus

Policymakers often face this tradeoff when making decisions. Here are a few examples.

Child safety seats on planes / At first glance, it may seem that the merit of a policy mandating child safety seats (CSS) on commercial airliners is obvious. After all, if regulatory policy requires CSS in automobiles traveling 60 mph, why would it not require CSS on airplanes traveling 600 mph?

Yet, as economist Thomas Sowell has observed, whether policymakers should mandate CSS on commercial aircraft is an empirical issue. If the cross-price elasticity between automobile travel and air travel is sufficiently large, the effective higher price of air travel would induce some families to substitute risky automobile travel for relatively safe air travel, resulting in a net increase in the number of fatalities. The riskier that highway travel is relative to air travel, the smaller the critical cross-price elasticity required to justify the public policy decision not to mandate CSS.

Since 1958, FAA regulations have permitted children under 2 years of age to sit on the lap of an accompanying adult on commercial flights, obviating the need to purchase a ticket for the child. This practice was without controversy over most of its history because of the absence of effective CSS for airplanes. This technological constraint largely disappeared over the ensuing decades, to the point that in 1982 the FAA issued its first regulation defining performance standards for CSS on commercial flights. This regulation essentially approved those safety seats that passed the FAA’s myriad safety tests, which included dynamic and rollover tests.

On August 25, 2005, the FAA announced that it would not mandate the use of CSS on airplanes. The agency indicated in its analysis that if families were forced to purchase additional airline tickets to accommodate children in CSS, some families would opt to drive rather than fly and driving represents a far more dangerous mode of travel. In other words, given the effective cross-price elasticities, the increase in the price of airfare for families would cause them to substitute relatively risky highway travel for relatively safe air travel. In the case of a family of four comprised of two adults and two infant children, the CSS mandate would effectively double the family’s cost of flying.

Aircraft safety certification / The redesign of existing aircraft is subject to recertification that can be considerably less stringent than the certification of all-new aircraft. The implicit presumption is that once-certified aircraft are “safe.” It is therefore not surprising that airline manufacturers have strong incentives to modify existing aircraft designs rather than design new ones. The original 737 was certified in 1967, but subsequent updates to the airliner have not undergone that level of scrutiny.

This prompts three questions. First, what is the effect of this policy on safety risks and does this amount to the circumvention of regulation? Second, when do differences in degree in “modifying” certified aircraft shade into differences in kind so that the end result is essentially a “new” aircraft masquerading as a certified aircraft? Finally, does this regulatory loophole explain what befell the 737 Max?

Recertification purportedly enabled Boeing to secure waivers on its 737 Max pilot-alert system that would not have been possible otherwise. Boeing claimed that the pilot-alert system required of new aircraft would cost $10 billion to implement (in 2013 dollars). The FAA therefore granted Boeing a waiver. The pilot-warning system is a primary focus of the FAA’s accident investigation into the 737 Max crashes.

It is important to note, however, that even if the FAA finds that the waiver was responsible, in whole or in part, for the 737 Max accidents, one cannot conclude that not granting the waiver and requiring recertification would have saved lives on net. Before drawing that conclusion, it would be necessary to compute the effect of the $10 billion price tag on the price of airfare to estimate the number of passenger miles diverted from the air to the highways. While no loss of life is “acceptable,” it is possible that granting the waiver saved lives on net given the increase in airfares that would have resulted if the waiver had been denied.

| TABLE 1 Effects of a 10% Airfare Increase on Annual Highway Fatalities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H‑A | %A Airfare | %A HWY Passenger Miles (Billions) | AHWY Passenger Miles (Billions) | HWY Fatalities Per Billion Passenger Miles | A HWY Fatalities |

| 0.01 | 10 | 0.1 | 5.50 | 7.28** | 40 |

| 0.06* | 10 | 0.6 | 33.01 | 7.28** | 240 |

| 0.10 | 10 | 1.0 | 55.02 | 7.28** | 401 |

| 0.20 | 10 | 2.0 | 110.05 | 7.28** | 801 |

| 0.30 | 10 | 3.0 | 165.06 | 7.28** | 1202 |

| 0.40 | 10 | 4.0 | 220.09 | 7.28** | 1602 |

| * “Analysis of Automobile Travel Demand Elasticities with Respect to Travel Costs,” by Jing Dong, Diane Davidson, Frank Southworth, and Tim Reuscher. Prepared for the Federal Highway Administration, August 30, 2012. Table 27.** “Comparing the Fatality Risks in United States Transportation across Modes over Time,” by Ian Savage. Research in Transportation Economics 43: 9–22 (2013). Table 2. | |||||

In 2017 there were 694 billion passenger miles flown domestically in commercial aircraft. Airfares averaged 13.7¢ per passenger mile. If the $10 billion cost of recertification were recovered in one year (and conservatively assuming there is no demand response in terms of reduced passenger air miles), that would equal 1.44¢ per passenger mile ($10 billion ÷ 694 billion passenger miles), or about a 10.52% fare increase. From Table 1, given a cross elasticity of 0.06, this would result in a 0.63% increase in highway passenger miles (10.52 × 0.06) or 34.73 billion passenger miles (0.0063 × 5502.42). That would result in an increase of highway fatalities of about 253 (34.73 billion passenger miles × 7.28 fatalities per billion passenger miles) per year. If the cost recovery time were 10 years, the fare increase would be 0.14¢ per passenger mile. That would translate to an annual fatality increase of 25 per year, or 253 over 10 years. Again, as a reference, prior to the 737 crashes, there were only 50 fatalities from domestic commercial air crashes over the previous 10 years.

Aircraft safety delegation / Investigation into the Boeing 737 Max crashes has revealed that the actual task of air-worthiness certification was carried out by Boeing employees rather than government inspectors. This reliance on self-regulation was based on the prohibitive cost of a large government safety organization as well as the premise that airline crashes were “bad for business” and therefore Boeing had strong incentives to police itself. It is noteworthy that Boeing recently reported its first annual financial loss in more than two decades.

What if Congress banned the practice? In a Senate hearing in March 2019, then–acting FAA administrator Dan Elwell testified that creating an organization to perform all the certification tasks now performed by Boeing employees would require a budget of $1.8 billion per year and about 10,000 employees.

If this cost were paid by those who fly (and conservatively assuming there is no demand response in terms of reduced passenger air miles), the cost would be 0.26¢ per passenger mile (1.8 billion ÷ 694 billion passenger miles), or about a 1.9% increase in airfares (0.26 ÷ 13.7). From Table 1, this airfare increase would increase highway passenger miles by 0.114% (0.06 × 1.9), or 6.27 billion passenger miles (5,502.42 billion passenger miles × 0.00114) and fatalities by 46 per year (6.27 × 7.28 fatalities per billion passenger miles). This fatality increase should be compared to the number of fatalities prevented by ending the delegation of safety certification.

Conclusion

The FAA’s investigation into the 737 Max crashes has already uncovered some disturbing facts and more are likely to come. We should anticipate demands from policymakers to ramp up air safety regulation along with a fist-pounding commitment that something like this should never be allowed to happen again. Of course, there are always opportunities to do better and Boeing and the FAA should avail themselves of all “efficient” opportunities to do so (i.e., those that save lives on net). Still, there is a real risk of reflexive over-regulation that costs more lives than it saves.

More stringent air safety regulation that increase airfares, perhaps dramatically, can result in a net increase in lives lost as travelers substitute high-risk highway travel for low-risk air travel. In the course of reviewing FAA practices, Boeing’s mea culpa, and the congressional rebuke that is sure to follow, it is critical that policymakers not lose sight of the sage advice contained in the Hippocratic Oath: “First, do no harm.” The greatest risk of all may be in allowing the regulatory pendulum to swing too far.

Readings

- “Analysis of Automobile Travel Demand Elasticities with Respect to Travel Cost,” By Jing Dong, Diane Davidson, Frank Southworth, and Tim Reuscher. Prepared For the Federal Highway Administration, August 30, 2012.

- “Child Safety Seats on Commercial Airliners: A Demonstration of Cross-Price Elasticities,” by Shane Sanders, Dennis L. Weisman, and Dong Li. Journal of Economic Education 39(2): 135–144 (Spring 2008).

- “Comparing the Fatality Risks in United States Transportation across Modes over Time,” by Ian Savage. Research in Transportation Economics 43: 9–22 (2013).

- “Does Self-Regulation Sufficiently Protect Consumers?” by Peter Van Doren. CQ Researcher, September 6, 2019.

- “Effects and Costs of Requiring Child Restraint Systems for Young Children Traveling on Commercial Airplanes,” by T.B. Newman, B.D. Johnston, and D.C. Grossman. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 157(10): 969–974 (2003).

- The Vision of the Anointed: Self-Congratulation as a Basis for Social Policy, by Thomas Sowell. Basic Books, 1995.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.