The U.S. airline industry is again under scrutiny. Since most economic controls over domestic commercial aviation ended in the late 1970s, traffic has grown by orders of magnitude, inflation-adjusted fares have fallen, computerization has revolutionized the way tickets are bought, frequent flier points have become a second currency, the range of routes available—provided we are willing to change planes—has expanded out of all recognition, and low cost carriers have come, and just as often gone. Most airlines no longer force us to pay for flying other peoples’ bags or for food we often did not want, even in the rare cases when it was palatable. Certainly the nature of the service we get has also changed, with less legroom, “poorer” and less refreshment, charges for checked bags, lines to board aircraft, and (heaven forbid) a passenger likely to be seated beside you. Flying is now transportation and not an experience; it has become a product.

The underlying economic philosophy that brought about the 1970s reforms was that, while not perfect, competition was generally preferable to the longstanding government micromanagement of the airline industry. As Alfred Kahn, the chairman of the Civil Aviation Board at the time of reform, put it, the prevailing view had changed to, “Whenever competition is feasible it is, for all its imperfections, superior to regulation as a means of serving the public interest.” That has remained the prevailing thinking, and it is unlikely to change significantly in the near future. Our concern here is, therefore, focused largely on whether competition could, with benefit to the traveling public, be taken further, and in particular whether market entry could, with advantage, be widened.

While the 1978 Airline Deregulation Act removed many of the legal barriers that limited the routes that individual carriers could serve and the fares they could set, it did nothing to open up the domestic market to international competition. Carriers still had to be “American citizens.” Subsequent “Open Skies” initiatives, and particularly those involving the European Union, have provided a more liberal international framework for U.S. airlines (see “Toward Truly Open Skies,” Fall 2002), but the domestic market remains protected from foreign competition. This regulatory thinking extends back to the Jones (Merchant Marine) Act of 1920, based on arguments that shipping between U.S. ports should be reserved for the U.S. fleet to ensure adequate capacity during times of national emergency (with the rather counterintuitive argument that it can be relaxed in times of emergency). This notion of restricting cabotage—the carriage of passenger, cargo, and mail between two points within a territory for compensation—was essentially extended to airlines when their strategic and economic importance was recognized following World War II. This situation has remained fundamentally the same ever since.

HOW THE 1978 AIRLINE DEREGULATION ACT IMPROVED AIR TRANSPORTATION

The deregulations of the U.S. air cargo market in 1977 and of scheduled passenger services in 1978 delivered considerable, almost immediate, net benefits to the American economy. The gains came in various forms, including lower real fares, more fare choices, more services, and more route options, with the result that the number of air travelers rose from 250 million in 1978 to 815 million in 2012, 736 million of them domestic. As for the effect at the micro level, a study by the American Air Transport Association in 1983 found that air fares in the new, deregulated environment had fallen by 67 percent compared to the levels the old regulated regime would have imposed. Looked at another way, over a full business cycle, the inflation-adjusted 1982 constant dollar–yield for airlines fell from 12.3 cents in 1978 to 7.9 cents in 1997, making airline ticket prices almost 40 percent lower over the cycle. Even those living in small communities that had been the subject of forced cross-subsidization under the pre-1978 regulatory regime benefitted. While the number of small community flights was cut by over 25 percent between 1970 and 1975, the flexibility and innovation stimulated by a freer market led to more such communities receiving non-stop air services in 1983 than in 1978. Added to this, the labor force enjoyed more job opportunities; the number of workers in the industry grew by 30,000 within two years of deregulation.

Following the inevitable transition period after liberalization, the industry continued to transform in response to market conditions and technology improvements. The longer-term picture, for example, has been for fares to fall in real terms, although this trend has flattened out in recent years when allowance is made for fees and the redemption of frequent flier miles. There have been changes in the structure of the industry, with a growth in the share of low cost carriers such as Southwest and JetBlue, and the increased hubbing of services by the legacy carriers that have consolidated as a result of mergers and attrition. Liberalization of international markets since the initiation of the United States’ Open Skies policy in 1979 has seen the growth of overseas networks and the development of various types of coordination with foreign airlines, most notably in the form of strategic alliances such as Star, SkyTeam, and Oneworld, offering seamless services.

THE MOUNTING TROUBLES IN AIRLINE MARKETS

While the trend over recent years has been for fairly stable fares, a periodic concern of the media as much as the traveler is that airfares tend to fluctuate considerably one year to the next, and often month-by-month. This adds uncertainty to decisionmaking, both for the business and personal traveler. Short-term fluctuations can be influenced both by the performance of the U.S. macro economy on the demand side, and by kerosene prices on the cost side (aviation fuel amounts to some 35 percent of airline costs). The services offered when paying the base fare have also changed. Many seats are now wholly or partly “paid for” using frequent flyer miles or similar rewards. There are now extra fees for some services previously included under the base fare; these include charges for checked bags and reservation change fees. Essentially the product has changed to reflect consumer demands and input prices.

What has become troubling in recent years is the change in seat availability in some particular types of market. One issue is the greater concentration of supply in the U.S. domestic market: there were 10 trunk airlines in 1979, but mergers and bankruptcies have left only American (21.1 percent, including USAirways, with which it merged in 2013), Delta (16.3 percent), and United (16.0 percent of the domestic passenger miles in 2012). Southwest (15.1 percent) and some other low cost carriers offered a form of dynamic competition for a time in the sense of a differentiated product, but the latter have largely gone. (Who remembers Tower Air, Vanguard, and Pearl?) And Southwest’s operating practices are increasingly looking like those of the legacy airlines, with large numbers of on-line passengers and the growth of hubbed services.

The deregulation of the 1970s, by removing entry quantitative controls, led to a considerable increase in services. It also increased the capability of individuals to access a wider range of destinations from their homes via the hub-and-spoke system of routings that emerged. This pattern has been reversed since 2007. The largest 29 airports in the United States lost 8.8 percent of their scheduled flights between 2007 and 2012, but medium-sized airports lost 26 percent and small airports lost 21.3 percent. The number of seats available has fallen faster than the seat-miles available, while the average return flight distance has risen from 2,279 miles in 2007 to 2,319 miles in 2010, and to 2,356 miles in 2013. This latter feature is largely a manifestation of the major carriers reacting to higher fuel prices, which have greater proportional effect on short-haul costs.

The reduction in capacity and the types of routes involved not only affect the services available, but also inevitably affect average fares. Average fares are declining because the composition of flights is changing. Fares on thinner routes, because of the lack of economies of density, often exceed those where demand is higher; smaller aircraft are generally used and overhead costs have a smaller base over which to be spread. The result is that airlines’ revenues collected when such thin routes become unprofitable and are closed fall more than in proportion to the decline in passengers carried, thus lowering the average fare across the entire network. Put another way, the shift to longer, denser routes takes higher fares out of the averaging process and thus gives the impression that fares are flat or declining.

Many of those issues may be transient and a reflection of immediate macroeconomic conditions. But there are extant structural issues that are legacies of the incomplete deregulation of 1978. The advent of jet and wide-bodied aircraft lowered costs in the 1960s and 1970s, and the 1978 Airline Deregulation Act caused the trend to continue in the 1980s and 1990s. Since then, real airline fares within the United States have largely plateaued; they fluctuate as fuel prices and economic growth oscillate and the temporary effects of mergers are felt. The challenge is to get the fare curve moving down again. The issue is not simply a matter of fares, but also the number and nature of services that are provided. People who no longer have ready access to air services are confronted with an infinite airfare—a fact not reflected in the airline airfare statistics.

THE NEED FOR CABOTAGE

A major problem is that the United States is still some way from a fully “deregulated” airline environment. In particular, non‑U.S. airlines cannot provide “cabotage services.” That means that the incumbent U.S. carriers are being protected from the full force of competition in the same way that U.S. manufacturing firms were in the 1970s, when their costs drifted higher than international competitors and their products became inferior. Cocooning a national market seldom leads to the efficient provision of services or to innovation. This is seen in the U.S. airline context where post-1978 carriers were aggressive and new service elements emerged (frequent flier programs being the most obvious), but more recently other markets have taken the lead in terms of service structures (e.g., the radial networks of Ryanair in Europe) and cost savings. It is also not as if this need for international competition has not been long recognized. Kahn made the point that “the government could actively attempt to make markets more competitive … above all by allowing foreign airlines to compete for domestic traffic either directly or by investing in American carriers.”

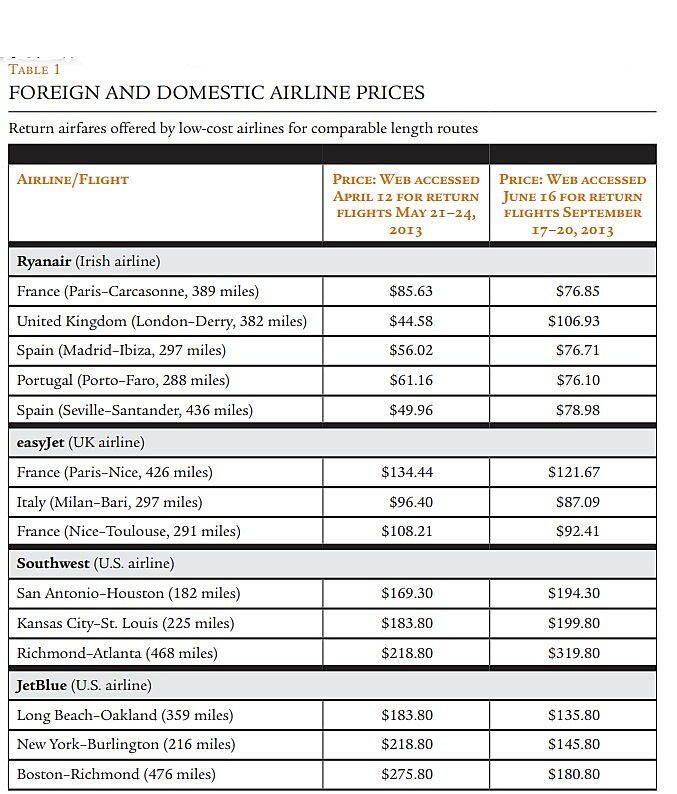

There are exceptions, but the fares of European carriers Ryanair, easyJet, Norwegian Air Shuttle, and the like are generally below those of supposed low cost U.S. airlines, let alone the legacy airlines. Some simple examples that reflect this are seen in Table 1, which compares the domestic fares of two U.S. low cost airlines with two European counterparts offering cabotage service over similar-length routes within a country outside the airlines’ own national borders. There are certainly some smaller low cost carriers in both Europe and the United States that may charge higher or lower fares for comparable-distance flights to those in the table—e.g., in the United States, Spirit’s fare for Fort Lauderdale–Orlando (181 miles) is $68.79, Chicago–Minneapolis (354 miles) is $78.79, and Las Vegas–Los Angeles (234 miles) is $61.78 for the dates used in the table—but their overall market shares are very limited.

Furthermore, the types of service that Ryanair and some other foreign carriers specialize in match the types that have largely been reduced in the United States. The average Ryanair return passenger trip, for example, is slightly over 1,000 miles. Despite the natural “gap-filling” role they could serve, the European carriers are not, however, permitted to offer their brands of service on this side of the Atlantic. Of course, travelers may not accept them (but many said that about Southwest 35 years ago), or domestic carriers may be stimulated to retaliate and offer comparable services, but either way customers would have a choice if cabotage were permitted. Given the experiences of smaller, domestic low cost carriers in the United States, such as Independence Air that operated between 2004 and 2006, it is tough to make it against the large incumbents and size does seem to matter. In the case of some foreign carriers, however, they are far from being “mom-and-pop” outfits and have deep pockets and modern, fuel-efficient fleets. For example, Ryanair has been consistently profitable (around $500 million in 2012), has a fleet of more than 300 Boeing aircraft with an average age of less than five years, and transported almost 80 million people in 2012. It is certainly experienced, aggressive, and competitive, and some other foreign carriers are as well.

THE CHALLENGES OF CHANGE

So why does it not happen? Why are politicians reluctant to let U.S. carriers face competition? One reason is self-interest. Incumbent airlines are powerful lobbyists, as are the labor unions. American airports are almost entirely publicly owned, treated largely as quasi-public utilities, and thus currently protected from some of the more aggressive business tactics found in other countries where airport fees have been lowered through market forces. Thus there is reluctance on the part of many airport authorities to have a fairly placid environment disrupted. The military also fears loss of the airlift that it currently enjoys under the Civil Reserve Air Force (CRAF) program that requires participating airlines to be U.S.-owned. Yet, allowing outside carriers into the United States is potentially likely to add to capacity in the country rather than replace it; further, one may question whether a reserve fleet of 552 passenger and cargo planes is optimal. Indeed, as far as the CRAF program is concerned, it has often been smaller charter carriers, such as World Airways, that have been used for those needs. It is difficult to see how CRAF counterarguments carry much weight, from a national welfare perspective, to justify keeping out foreign carriers.

There are also concerns expressed by labor, which fears that foreign airlines would reduce unions’ bargaining power and thus their terms of employment. The fear persists despite the numerous concessions that labor has made over recent years to keep U.S. domestic carriers in business or have been forced on it as airlines have entered and exited Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Recent changes in pilot qualifications that have slowed the supply of new pilots in the United States, and a growing world market for their skills, are also beginning to put upward pressures on their wages and terms of employment.

Arguments have also been put forward that preventing cabotage has had minimal effect and that the costs to foreign carriers entering the U.S. market as effective competitors are prohibitive, and thus outside airlines will simply not offer services. That may well be so in the case of the bigger, traditional foreign airlines. They are already largely integrated with the U.S. legacy carriers in the three major strategic alliances and enjoy the passenger feed from existing U.S. domestic services. Those foreign airlines may not want to disrupt the larger, essentially globally orientated arrangements to compete in the U.S. market. It is the very large low cost carriers that would seem more likely to seek cabotage rights. Their fleets and experiences are mainly in shorter, institutionally simpler haul markets in which a standardized fleet can be used, rather than in providing international hub-and-spoke services. But beyond that, even if it is true that allowing foreign entry would have little effect for passengers in the U.S. domestic market, then why prevent it?

Allowing cabotage at a time when several major airline mergers have just taken place also seems timely, particularly given some misconceptions about what genuine competition means. The U.S. Justice Department, for example, initially blocked the 2013 merger of USAirways and American on the grounds that it would “eliminate competition” by leaving only three network carriers in the market. It added, “[C]ompetition from Southwest, JetBlue, or other airlines would not be sufficient to prevent the anticompetitive consequences of the merger…. Southwest, the only major, non-network airline, and the other smaller carriers have networks and business models that differ significantly from the legacy airlines.” But history has shown that it is not competition in terms of numbers of like suppliers that has had the biggest impact on industries, but rather the impact of “outliers” that change the competitive paradigm.

To take two examples in the airline context; American Airlines gained a powerful position in the 1980s through its innovative frequent flyer program, its pricing using the Sabre computer reservation system, and its cost savings with a two-tier wage structure. Later, Southwest had similar effects by developing the low cost model. Again, the impact spread, not only because of Southwest’s own growth, but because other airlines, including subsidiaries of legacy carriers (such as United’s Ted brand) have sought to emulate Southwest. In both cases it was not the force of pure competition that reduced the price of an existing “product,” but rather the creation of a new product or the significant morphing of an existing one. Allowing foreign carriers into the U.S. domestic market could provide a similar stimulus.

OPERATIONALIZING TRANSITION

In addition to issues regarding the intrinsic merits of opening up the U.S. skies to foreign airlines, there are challenges in deciding the form any transition would best take. The air transportation reforms of the late 1970s represented a “Big Bang” approach to regulatory policy; changes were introduced and implemented over a very short period. This contrasts to the gradualism that has characterized some other cases, most notably the European Union airline market where reforms came in as a series of “Three Packages.” The advantage of the U.S. approach was that the transition costs imposed on airlines, and de facto on passengers, were relatively short-term (though significant). There were some stranded costs as airlines modified their activities and adjusted schedules, fleets, and crew composition, and some carriers that made poor decisions left the market, but those were over quickly. In contrast, a more incremental approach would have reduced short-term disruptions but increased the time before the benefits of reform began to flow. The gradualist system is also more prone to capture and political manipulation at the various stages of the process, allowing incumbents to protect their vested interests to the disadvantage of new entrants. In Europe, some airlines like Alitala and Olympic continued to clamor for “restructuring finance” for many years after the reforms.

A number of interim or partial approaches have been suggested as alternatives to pursuing a “Big Bang” opening of the U.S. domestic airline market and letting foreign carriers compete directly with U.S. carriers. Those suggestions are made largely from the perspective of meeting some of the political concerns with initiating free competition too rapidly. One option is to allow foreign carriers to tender for subsidized services that come under the Essential Air Services (EAS) and the Small Community Air Service Development (SCASDP) programs. The former program, costing $190 million in 2012, was established in 1978 to allow the U.S. Department of Transportation to subsidize airlines serving rural communities deemed otherwise unlikely to receive any scheduled commercial service. SCASDP goes beyond providing basic services and is intended to stimulate rural economies. Critics have pointed out that some subsidized airports under the EAS are less than an hour’s drive from an unsubsidized facility, and have questioned the economic efficiency of both EAS and SCASDP.

The difficulty with opening up routes supported by either program is that entry by foreign carriers is unlikely to be significant—and certainly not on a scale to produce any convincing results in terms of offering competition to the major carriers. The subsidies are short-term and there is no guarantee of renewal, making the entry into those market risky and unlikely commercial propositions. Further, at present domestic carriers involved in the two programs often treat subsidized routes as appendages to other parts of their networks—a situation that would not apply to foreign airlines limited to EAS and SCASDP.

It has also been suggested that for cities that once served as hubs prior to the recent consolidations of U.S. carriers, their markets should be opened to allow foreign airlines to serve them. This would not only provide additional services to those locations, but may be seen as an experiment as to the types of foreign carrier that would enter the market, and with what consequences. The Brookings Institution’s Clifford Winston, for example, argued along those lines in a Nov. 20, 2012, New York Times op-ed:

One possible solution is to take a half-step toward opening up domestic markets and allow foreign carriers to serve any midsize and regional airport in the U.S. that has lost service in the past few years. New entrants would be able to integrate those markets with their international routes, something that could put many smaller American cities on the global business map.

The difficulty here, even if politicians representing areas with an ongoing hub were willing to accept cheaper airlines exclusively operating in other parts of the country, is that foreign airlines, even if more efficient than their U.S. counterparts, are unlikely to be attracted to providing services in markets that have a poor track record in terms of profitability. The risks are clearly high, especially if the expectation of longer-term expansion into wider markets is denied. Arguments that providing such services would provide feed for the international services of foreign carriers are also not persuasive. The long-haul foreign carriers operating into and out of the United States tend to be high cost legacy carriers and not low cost airlines. In addition, most of the major foreign carriers serving the U.S. market belong to a strategic alliance, and thus it would seem more likely that they would already be receiving feed from many of the defunct domestic routes of their partners.

But there is also a more fundamental issue with the partial hub penetration approach: it, in many ways, may be seen as the short-ends of a wedge to re-regulation. There would be a need to segregate “areas” of airline activity that foreign carriers can engage in and areas reserved for domestic carriers in the same way that the old Civil Aeronautics Board licensed services to particular carriers. This move toward partial re-regulation favored by Winston also requires considerable knowledge of the network economics of the industry. When an airline de-hubs from an airport, it seldom withdraws all services and, in addition, other domestic carriers take up some of the slots to complement their own networks. The drawing of borders between the monopoly domain of domestic airlines and markets open to foreign entry would depend on numerous judgments over which airports fall into each category. Not only is it uncertain how such criteria could be drawn up, but the airline industry is dynamic and, from the experiences of the pre-1978 situation, regulatory agencies have not proved fleet enough of foot to keep up with this. Political interference would also seem inevitable; moving the boundaries between foreign allowed/foreign banned routes is hardly likely to be considered on efficiency grounds alone.

Markets work well when there is competition; in air travel, it keeps incumbent airlines on their toes and stimulates both them and potential entrants to be innovative. Hence the U.S. market shouldn’t be limited to U.S. airlines.

A legally separate but operationally entwined issue with cabotage is the matter of foreign investment in U.S. airlines. At present this is limited, and the general rule is that for European airlines, equity investment may be up to 49 percent, but with voting shares limited to 25 percent. U.S. airlines must also be American “citizens” with U.S. nationals as chief executive officers. As with cabotage, the rationale for this is partly military, aimed at ensuring that there is enough airlift capacity in times of national emergency. The need for this sort of capacity protection in the context of the efficiency of the existing system and its longer-term viability has been questioned. Other countries do not adopt such an approach. Whether allowing greater foreign investment in the U.S. commercial fleet would improve or weaken the reserve capacity is uncertain, but it would probably enhance the commercial viability of the U.S. passenger civil airline industry by opening more sources of finance and allow for more integrated services with foreign alliance partners.

Conclusion

In sum, the 1978 Airline Deregulation Act only partially liberalized the U.S. domestic airline market. One important restriction that remains is the lack of domestic competition from foreign carriers. The U.S. air traveler benefited from the country being the first mover in deregulation, and this provided lower fares and consumer-driven service attributes some 15–20 years before they were enjoyed in other markets; the analogous reforms in Europe only fully materialized after 1997. But the world has changed, and so have the demands of consumers and the business models adopted by the airlines. What was seen after the 1978 reforms in the United States is that market forces, albeit not always perfectly, delivered many of the sort of air services that travelers wanted and the institutional structures—ranging from low cost airlines to global distribution systems for ticketing and computer information systems—to deliver them. But remaining regulations still limit the amount of competition in the market and, with this, the ability of travelers to enjoy even lower fares and a wider range of services.

Much is often made in the media of short-term frictions in the market (for example, oscillating airfares because of a volatile jet fuel market, lost baggage, and flight delays), and there is an obvious and justifiable reason to voice concern over those issues. This is particularly so if the adverse patterns persist for any length of time. Of more importance, however, is the recent trend (that has extended beyond a few years) for the capacity of the industry to decline nationally, but more so in some local, thinner markets. Those are the sorts of markets that are not attractive to legacy hub-and-spoke operations, but can be commercially viable for radial operators that provide services from a base.

A solution to some of those short-term difficulties is to allow market forces to work even more efficiently. Markets work well when there is competition; it keeps incumbent airlines on their toes and stimulates both them and potential entrants to be innovative. In the context of the U.S. domestic airline industry, the market would be more competitive if it were not just limited to U.S. airlines.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.