The Occupational Safety and Health Administration recently sought comment on proposed standards to reduce occupational exposure to respirable crystalline silica. The agency faces multiple challenges in devising a regulatory approach that will meet its statutory goal of reducing significant risk. In a comment filed on the public record, University of Alabama law professor Andrew Morriss and I recognize OSHA’s challenges; however, we find that the greatest obstacle to reducing risks associated with silica exposure is not lack of will (on the part of employers or employees), but rather lack of information. Our analysis concludes that the proposed rule will contribute little in the way of new information and, indeed, may stifle the necessary generation of knowledge by precluding flexibility for experimentation and learning.

Almost 40 years in the making / Prolonged workplace exposure to free crystalline silica is associated with scarring of the lungs, leading to silicosis—a progressive, incurable disease that impairs respiratory function. Yet, silica is ubiquitous. Also called silicon dioxide or (more commonly) quartz, crystalline silica is the second most common mineral in the earth’s crust and occurs abundantly in sand, soil, and rock. It is used to manufacture a wide variety of materials, including glass, concrete, and abrasives. Google “silica” and you’ll find ads extolling its benefits as a nutritional supplement and beauty treatment.

OSHA first established a maximum permissible exposure level for crystalline silica in 1970 by adopting a consensus industry standard. Unfortunately, the form of that standard was obsolete by the time it was adopted, and OSHA issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking to modify it in 1974, but took no further action.

Then, in 1994, OSHA identified crystalline silica as one of a few top-priority safety and health hazards, and, two years later, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded that “crystalline silica inhaled in the form of quartz or cristobalite from occupational sources is carcinogenic to humans.” In 1998, OSHA listed regulation of silica on its semi-annual agenda of upcoming regulatory actions and, by the fall of 1999, set a deadline of June 2000 for issuing a proposed rule. The agency missed that deadline.

In 2002, OSHA set a new deadline of November 2003 and listed the proposed rule as one of its top priorities. This deadline kept slipping, however, until February 2011, when OSHA sent a draft of the rule to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs for interagency review. The review took an unusually long 2.5 years to complete and culminated in OSHA publishing a proposal on its website on August 23, 2013. The agency then granted several extensions to the comment period, which ultimately closed this past February, followed by public hearings in March.

OSHA’s proposal has been greeted with enthusiasm by labor unions and organizations such as the American Thoracic Society, and criticism by builders and contractors who express concern that the rule would impose unnecessarily prescriptive and costly requirements. (OSHA estimates the rule will cost $637 million per year.) In a twist that can only heighten discord, OSHA realized after conducting a preliminary regulatory impact analysis that its proposal would affect an industry it had not previously considered: hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” which is the subject of heated political debate.

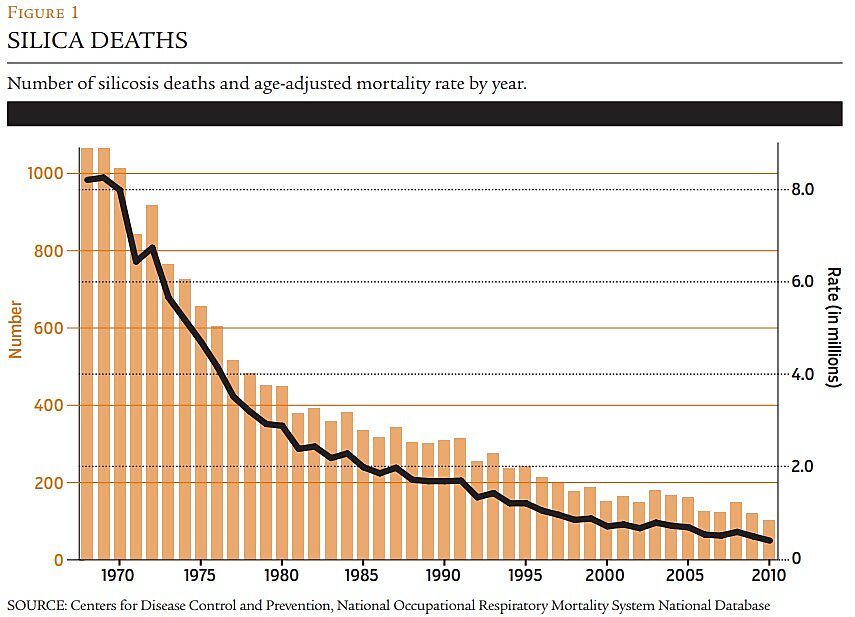

Unrealistic benefit estimates / Our comment focused on OSHA’s estimated benefits of the proposal. The agency estimates that “the proposed rule will save nearly 700 lives and prevent 1,600 new cases of silicosis per year.” But those figures, as well as OSHA’s conclusions that crystalline silica poses a significant risk and that its proposed controls will substantially reduce that risk, are based on data that are at least a decade old. They also ignore evidence (such as the trends shown in Figure 1 of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) that adverse health effects from silica exposure have declined dramatically over the past 45 years.

Contrary to the observed trends, OSHA’s determination of the significance of the risk and its estimates of the risk reduction potential of the proposed regulation implicitly assume that, without the implementation of the agency’s proposed regulation, exposure and health effects would remain as they were over a decade ago. Not only is this analytical approach certain to overstate the risk-reduction benefits attributable to the rule, but it misses opportunities to identify and encourage successful risk-reducing practices. Despite using an unrealistic baseline assumption of no further reduction in risk absent the rule, OSHA’s estimated benefits are less than what would be projected if past trends were simply to continue.

Focus on generating knowledge / Before OSHA can properly dispatch its statutory authority to identify and reduce significant risks, it must first understand what forms of silica lead to those risks. Further, to devise solutions to address remaining risks, OSHA’s analysis should at least recognize the observed declines in silicosis mortality over the last several decades and work to understand the reasons behind those encouraging trends.

To address the information problem that is at the root of continued risks from silica exposure, OSHA should follow the guidance of President Obama’s Executive Order 13563 and devise approaches that provide information, maintain flexibility for experimentation, and encourage the generation of knowledge.

OSHA’s permissible exposure level (PEL) and engineering controls give a false impression of precision, and OSHA’s analysis assumes that the controls it has specified will result in compliance with the new PEL. These are merely assumptions, however, as OSHA is unable to connect risk reductions to specific requirements. Perhaps more important, such standards provide no incentive for increasing knowledge about silica hazards in the workplace; indeed, they may even discourage it by focusing attention on compliance with the standard rather than on harm reduction. Given the costs and time involved in changing OSHA regulations, the design-based standards are unlikely to encourage investigations by private parties into developing information as to the relative hazard of different forms of silica or practices likely to reduce risks.

OSHA’s proposal identifies two regulatory alternatives that it should seriously consider because they are more consistent with President Obama’s executive orders directing agencies to “specify performance objectives, rather than specifying the behavior or manner of compliance that regulated entities must adopt.” OSHA’s Regulatory Alternative #7 “would eliminate all of the ancillary provisions of the proposed rule” so that the PEL would serve as a performance standard and would allow employers and employees to determine the most effective way to meet that standard. OSHA’s Regulatory Alternative #9, which would phase in a more stringent standard over time as more information becomes available, could have benefits not only in reduced compliance costs, but in knowledge-generation and sharing.

Regardless of the approach OSHA takes in the final rule, it should lay out a clear plan for conducting retrospective review, as required by President Obama’s Executive Orders 13563 and 13610. This review should include an explanation of how the agency will measure exposure and risk and how it will evaluate the effectiveness of the different components of the final rule.

Readings

- “Defining what to Regulate: Silica and the Problem of Regulatory Categorization,” by Andrew P. Morriss and Susan E. Dudley. Administrative Law Review, Vol. 58, No. 2 (Spring 2006).

- “Public Interest Comment on the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s Proposed Standards for Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica,” by Susan E. Dudley and Andrew P. Morriss. The George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center, December 4, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.