A lawyer in Illinois recently billed a client for working 180 hours in a week. The client paid the bill, even though a week is only 168 hours long. The client wasn’t being foolish—he knew how many hours are in a week. Instead, he saw value in paying the lawyer for what he asked. After all, the lawyer had just produced a major, hard-fought victory.

The case involved a construction firm that was facing bankruptcy. The company approached its largest unsecured creditor, which was the main bank in the community, and asked for another loan. The firm secured the loan by pledging its trucks, inventory, and equipment. Shortly thereafter, it went bankrupt and the bank took over the assets to cover not only its secured debt, but also its earlier, unsecured loans. That’s not supposed to happen; unsecured creditors go to the back of the line when it comes to divvying up assets.

The trustee in bankruptcy asked a few top law firms to take on the case against the bank, but they demurred; suing the biggest financial institution in the area was not for the faint of heart, and none saw much of a chance for a great payday. But one lawyer leapt to take the case. He secured the job by suggesting to the trustee that if it could be demonstrated that the bank made the final loan solely to get its hands on assets to cover the unsecured loan, the bank would have to disgorge every dime it took from the construction firm and pay penalties to boot.

He won the case and the trustee recouped millions of dollars from the bank, an order of magnitude more than he ever conceived he would recover for the other debtors. After the ruling, the bankruptcy judge convened a short hearing to wrap up loose ends and approve the trustee’s expenses. When the judge noted the lawyer’s bill included a week when he billed 180 hours, the trustee made it clear he would not object to that or any other item in the bill. The judge approved it. The trustee said the fee went beyond saying “thank you” for a job well done: he wanted to pay his lawyer a decent fee to let the rest of the bar know that he would take care of anyone willing to take on a big bank or who did more than just go through the motions and rack up hours.

It is an apt analogy for executive pay: boards (and shareholders) have every reason to reward chief executives and other officers who take over moribund companies and dramatically improve their value. To jump on a sinking ship can be a career-ender for an executive. Boards should want to reward CEOs who take on such challenges and succeed not only as a way to show their appreciation, but also to provide a tangible signal that the next guy who pulls off this trick for them will also be amply rewarded.

CEO compensation disclosure rule / The problem in executive compensation is that there are plenty of CEOs who receive outsized rewards for merely minding the store. And, of course, there are examples where CEO pay resembles crony capitalism and sizeable bonuses are completely unnecessary to retain the current CEO or attract a talented successor. Much of that pay represents an expense that produces nothing for the stockholder.

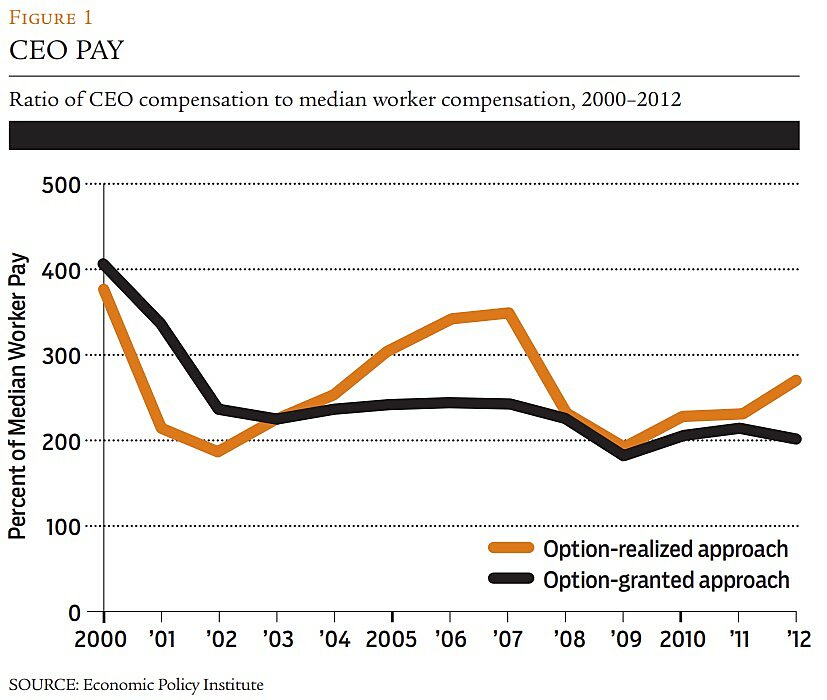

Despite the advent of new analytical measures of performance and a pause in CEO compensation growth (CEO pay growth has slowed dramatically in the last decade, as shown in Figure 1), Congress apparently thought that the private sector needed more help on this issue. The Dodd-Frank Financial Reform Act of 2010 tasked the Securities and Exchange Commission to implement a rule requiring corporations to regularly publish the ratio of their CEOs’ compensation (including benefits and bonuses) to the median compensation of their work forces.

While it may seem churlish to object to merely asking firms for one more datum, this piece of information is all but useless in shedding light on the issue. Whether a CEO makes 20, 200, or 2,000 times as much as the median compensation of the firm’s employees provides no particular insight as to whether a CEO is fairly compensated.

For example, a company that operates retail outlets will have a host of workers earning the minimum wage. How does comparing its CEO pay ratio to a company that outsources all low-skilled jobs to service companies provide useful shareholder information? A similar issue arises when comparing a financial services company with thousands of branches across the country to another financial services company with no retail outlets. By this metric, the active retailer will seem grossly overpaid compared to the New York City investment bank CEO, regardless of salary or performance.

Perhaps we should exclude retail employees in this instance, or else impute a reasonable number of them for the investment bank to make this metric compelling. Or, more logically, the SEC should just do away with such a flawed measure altogether, as common sense would dictate.

The pay-ratio statistic is also susceptible to manipulation and creates incentives Congress could never have intended. For instance, a few years ago food-maker Sarah Lee’s CEO, Brenda Barnes, spun off all of its bakeries, choosing to contract out all production and focus its attention on marketing and research. In one fell swoop, the CEO–median worker compensation ratio plummeted. Did it go down too much? What are the relevant companies to compare its pay ratio now? How would the ratio inform investors in any worthwhile way? Besides, if the CEO pay ratio would prove to be a meaningful metric to investors, CEOs would have more of an incentive to contract out any activities primarily done with low-wage workers. Is this necessarily a good thing?

Large costs, small benefits / Another problem firms may face when trying to calculate the CEO pay ratio is that it necessitates compiling data in a way that most companies are not accustomed to doing. As a result, it will require companies to expend some effort (and resources) to calculate it. Major corporations do not typically centralize payroll operations; if a company owns several divisions that are working fine, it often leaves them alone with such arcane issues such as meeting payroll. They may no longer have this luxury.

Computing compensation—as opposed to just wages—makes this even more difficult. It requires examining health insurance costs, pension costs, and every other fringe benefit provided, and then ascribing a portion of the cost to each employee. There’s no “quick and dirty” way to do it—the value of health insurance depends greatly on an employee’s age and family situation, and of course pension benefits vary with income and tenure for most defined benefit plans.

Companies that have operations overseas where the government provides a large degree of health care need to think about how to attribute that to their compensation costs. Generally, income taxes are higher in places with more generous public health benefits. That suggests that a company needs to consider those tax costs when trying to calculate the compensation of its median employee. The provision specifically includes all overseas workers, so there’s no skirting the issue. Some multinationals operate in dozens of countries, and compiling data on all forms of employee compensation, dealing with third-party administrators, and then converting those figures into a pointless ratio for regulators makes for an expensive annoyance.

Real costs and virtually zero benefits to the company add up to a rule that flunks any bona fide cost-benefit analysis, but that is of little concern to Congress and the SEC. However, it may turn out to be a bigger concern to the courts. By law, SEC regulations must promote capital formation, increase efficiency, or facilitate investor protection. It’s almost impossible to argue with a straight face that any of those goals are advanced by this rule.

The SEC’s Proposal and Request for Comments sheepishly admits that it likely contains no notable benefits. It states, “Neither the statute nor the related legislative history directly states the objectives or intended benefits of the provision or a specific market failure.” It also frankly admits the possible absence of any tangible benefits.

The projected compliance costs are large: one group of trade associations estimates it would cost roughly $7.6 million per company to compile a satisfactory pay ratio, or nearly $30 billion in total for the 3,830 companies estimated to be covered by the provision. Even if one assumes average compliance costs of $250,000 per firm, there are still annual costs to the economy approaching $1 billion.

Not surprisingly, the SEC’s cost estimates are much lower, as the agency only quantified the paperwork costs of outside professionals to derive the pay ratio. The SEC estimates that the rule would impose 545,792 annual hours of paperwork (which works out to 190 hours per company) and $72.7 million in costs. Those figures differ from the trade associations’ by a couple orders of magnitude. Given the paucity of analysis supporting the SEC’s estimates, our hunch is that the actual number hews closer to the industry estimate.

The SEC’s Proposal and Request for Comment sheepishly admits that it likely contains no notable benefits. It also admits the possible absence of benefits.

Low-balling compliance costs isn’t unusual for the SEC. Consider the agency’s “conflict minerals” rule, which was also promulgated in accordance with Dodd-Frank. Under the rule, firms are required to report whether their products were manufactured using minerals extracted in the Democratic Republic of Congo or nearby areas, where valuable minerals are mined and sold to fund military conflict. The SEC originally estimated that the rule would impose 153,000 burden hours and $71 million in costs on firms, but after an avalanche of complaints the agency raised the estimates to 2,225,273 burden hours and $4.7 billion in total costs. That’s a 650 percent increase. But even if the SEC’s initial estimate for the compensation ratio rule proves to be the final figure, it would still be the ninth most expensive Dodd-Frank rule to “fix” an issue that in no way contributed to the financial crisis.

Baseball’s dilemma / Paying salaries above what the market would dictate is a problem that afflicts more than the executive suite. Major League Baseball clubs have been dealing with this problem for decades, though it became especially acute during the early free market era before the advent of advanced performance metrics.

For instance, in the 1990s the Chicago Cubs had an outstanding right side of the infield in future Hall of Fame second baseman Ryne Sandberg and three-time all-star first baseman Mark Grace. In 1993, Sandberg became the highest-paid player in baseball, signing a contract worth $6 million a year. The next year, the team gave Grace a similar contract after his agent argued that since Grace’s offensive numbers were similar to Sandberg’s, he deserved a similar salary.

But it was an erroneous comparison. Second base is a defensively vital position, and throughout baseball history there have been only a few players who could both play the position well and hit for power. Sandburg was one of them, as attested by his nine Gold Gloves (awarded to the league’s best defensive player at each position), seven Silver Sluggers (league’s best offensive player at each position), 10 All-Star Game appearances, and his 1984 National League Most Valuable Player award. According to the advanced baseball statistics website FanGraphs, between 1984 and 1994, Sandberg’s play gave his team almost twice as many wins as his closest National League counterpart. Grace, on the other hand, was a singles hitter playing a position normally manned by a power hitter (though Grace was a good fielder, winning three Gold Gloves). In his prime, he was only a slightly-above-average hitter for a first baseman, yet his pay put him above most of his first base peers.

Today, most teams would not dream of paying a singles-hitting first baseman anywhere near the salary of a power-hitting, slick-fielding second baseman (witness Robinson Cano’s mammoth new contract with the Seattle Mariners). Teams have access to much more sophisticated statistics that capture a player’s true contribution to his team, such as Wins Above Replacement (WAR) or Weighted On-Base Average (wOBA), than they did two decades ago. Using those measures, it is hard to justify playing Grace regularly at first base, let alone paying him a superstar’s salary. Few teams would do so today.

But despite our ability to precisely quantify a player’s performance, there are still many players who earn much more than their contributions on the field can justify. Consider the most recent contracts for the New York Yankees’ Alex Rodriguez (10 years, $252.87 million) and Alfonso Soriano (eight years, $136 million) and the Los Angeles Angels’ Alex Pujols (10 years, $240 million).

What’s the point of grumbling about those? It’s that paying CEOs what they truly deserve is an even more difficult than paying ballplayers. Many of the metrics used (such as comparing one CEO to his peers in the same industry or of companies the same size) are facile and easy to manipulate, not unlike the data baseball agents torture in their quest to get big paydays for their clients. The economist Richard Thaler once observed in the New Republic that there is no business in the world where employers can measure the performance of their workers as precisely as baseball. We’re hard-pressed to name an industry that is more competitive than the major leagues. If those guys regularly end up awarding contracts that overpay players, perhaps we should acknowledge that fairly compensating talented individuals is difficult.

Metrics for CEO performance /There is a need for baseball-like advanced statistics to provide a better understanding of the true value of a CEO. Fortunately, this analysis is already happening, as various economists and companies that work on executive compensation issues have devised metrics that aim to capture CEO performance as well as ways to connect compensation to performance.

For baseball players, there is no single metric that can fully capture value. The aforementioned WAR is the one most commonly used by today’s analysts, along with a variety of new metrics that attempt to capture defensive performance. Likewise, analysts who try to capture a CEO’s contribution focus on earnings growth, revenue growth, and returns, all of which have a strong correlation with Total Shareholder Return (TSR). A recent study by Farient Advisors suggests that earnings growth (whether earnings per share, net income, or operating income) had the highest correlation to shareholder value across industries.

If Dodd-Frank lowers CEO compensation, there is no reason to think that the savings would be used to increase the wages of rank-and-file employees.

However, those metrics don’t work quite the same for every industry. For instance, energy, banking, and pharmaceuticals showed a particularly low correlation between earnings growth and TSR, which can be attributed in part to the difficulties in predicting future value in early-stage life sciences companies, as well as the inherent uncertainty faced by industries subject to considerable regulatory oversight. It’s a difficult task, of course: while we may have better measures of company performance these days, the extent to which we can attribute a company’s long-term profits to the CEO’s performance is still (and will always be, at least for most industries) difficult or impossible to discern.

Using rules to “send a message” / The point of forcing firms to calculate and publish the CEO–median worker compensation ratio is, of course, to generate outrage in the hope that it will provoke a lower ratio. But it’s unclear how this helps workers, and that is the relevant issue.

Why have unions been the most fervent advocates for this regulation since Congress first contemplated its inclusion in Dodd-Frank? Do unions expect that companies will lower this ratio by boosting median wages? If so, it is difficult to conceive why that would happen. It will always be cheaper for a firm to lower the ratio—if it ever did find it expedient to do so—by reducing the CEO’s compensation. And if it lowers CEO compensation, there is no reason to think that the savings would be used to increase the pay of rank-and-file employees, whose wages are largely dictated by the local labor market. Besides, it’s more likely the firm would lower this ratio through subterfuge of some sort—perhaps by jettisoning low-paid workers or deferring a CEO’s compensation until he leaves. The most likely outcome of the rule is no change in firm behavior whatsoever, except that they will be forced to expend effort and resources to calculate a statistic that will be of no use to them, their boards, their shareholders, or investors.

SEC rules are not meant to serve as an ideological bulletin board for whatever political party happens to be in power. But that’s precisely what the authors of the CEO pay ratio rule had in mind: it is intended to convey a message that CEOs are paid too much.

There’s some evidence that the courts have a jaundiced eye for such political shenanigans. In January, lawyers arguing over the validity of the conflict minerals rule before the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia suggested that the regulation is primarily intended to be a “shaming statute” or “scarlet letter” freighted with ideological intent, and that it serves no public purpose. The court seemed inclined to agree with that perspective.

Mandating the regular publication of a crude gauge of relative CEO compensation is a costly exercise that fixes precisely nothing.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.