The regulatory process is consistently criticized by many observers for being opaque, political, and unaccountable. A rule’s development can stretch years between its initial proposal and final publication. The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) plays a central role in the regulatory process through its authority to review and “authorize” rules from executive agencies. It has, therefore, also been central to the debate over how proposed rules change as they move through the process.

Public interest advocates suggest that OIRA is mostly attentive to the concerns of business and therefore attempts to weaken rules by delaying their implementation, diluting their provisions, and substituting its own judgment for that of the initiating agency. On the other hand, conservatives complain that OIRA merely rubber-stamps agency action, delaying but rarely vetoing rulemakings that would fail a cost-benefit test.

Neither side currently has overwhelming empirical evidence to support its position. What quantitative research there is on OIRA’s effect on proposed rules tends to focus on the final finding of the review, whether “approved without change,” “approved with change,” or (rarely) “returned” to the agency for further analysis. The Center for Progressive Reform, a pro-regulation group, found that OIRA changed up to 84 percent of health and safety rules. Regardless of whether such changes are decried for reducing safety or hailed for promoting efficiency, existing research offers some support for the view that OIRA does revise the content of proposed rules.

But those studies do not offer a means to assess the practical effect of the OIRA alterations. Simply recording percentages of rules “changed” by OIRA fails to account for what sort of changes are made. “Approved with change” is a broad category that could contain anything from minor technical tweaks to removal of entire provisions. Claims that OIRA consistently deflates benefits, inflates costs, and hollows out public health and safety measures ignore the diversity and complexity inherent in a system producing thousands of rules each year. While critics can point to notable examples when OIRA review did produce such changes, it is questionable whether those anecdotes constitute a pattern.

To develop a better understanding of OIRA’s effect on rulemaking, we conducted a review of the changes in cost and benefit estimates between proposed and final rulemaking stages. This study provides a better measure of the gravity of rule changes and adds empirical grounding to a debate driven overwhelmingly by competing anecdotes.

Changes in Cost / We analyzed 160 final rules (excluding routine Federal Aviation Administration regulations) published in 2012 and 2013 that underwent some form of review. OIRA reviewed 111 of those rules, while independent agencies produced (and reviewed) the other 49. According to our analysis, the average net change in cost between the proposed and final rules was an increase of $137.1 million. The average percent change was an increase of 401 percent. However, a few rules with dramatic cost increases artificially elevated the averages.

A plurality of rules had increased costs: 74 (46 percent) had higher costs in the final stage than when originally proposed; 46 (28 percent) had lower costs; and 40 had no change (25 percent). In the aggregate, the positive changes represented increased costs of $35.6 billion (an average change of $481 million) while the negative changes decreased costs by $13.7 billion (an average decrease of $297 million). Thus, while cost estimates are more likely to increase than decrease during the rulemaking process, the direction of change is not exclusively positive.

Differences between the proposed and final rule can arise from a variety of factors. Changes may be caused by the addition of analyses not present in the proposed form (such as determining “major” rule status under the Congressional Review Act). Or analyses may have been present in the original edition of the rule, but were updated as new information became available. In either scenario, the actual content of the rule is unchanged, with the increase in costs reflecting procedural decisions by agencies and OIRA. Finally, cost and benefit changes could reflect substantive alterations to the actual content of the rule. Because of those different possibilities, it is unclear whether increasing cost estimates should be applauded as a more accurate accounting of the rules’ effects or decried as a gradual expansion of rules’ reach over time.

Cost Changes by Agency / When possible, net changes were considered on an agency-by-agency basis. Few agencies produced enough final rules in the period studied to allow for meaningful conclusions, but financial regulators (in the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Commodities Futures Trading Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission, and Department of the Treasury), health care regulators (in the Department of Heath and Human Services and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) and the Environmental Protection Agency all had sufficiently large sample sizes (more than 25).

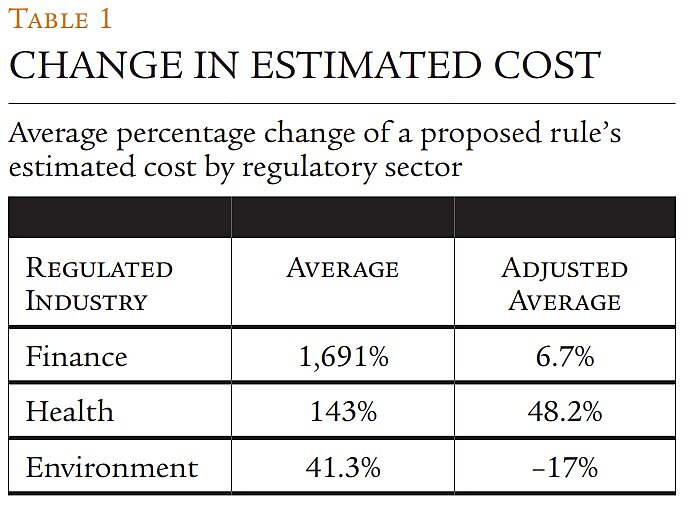

The first column of Table 1 presents the raw average percentage change in a proposed rule’s estimated cost. The next column, “adjusted average,” excludes the three rules with the largest percent changes in each category, so as to better capture the typical change.

The difference between the two columns confirms that the data are subject to a large amount of variability. The finance rules had the largest disparity in percentage changes, as shown by the dramatic reduction between the average and the adjusted average. The dispersion in the other two areas was not nearly as pronounced.

The HHS generally seems to have the largest cost increases between proposed and final stages. Social regulations often have wide scopes, which could explain the agency’s difficulty in accurately projecting costs. Despite its reputation for producing costly rules, the EPA’s cost estimates appear to remain stable throughout the process, in what might be a testament to OIRA’s effectiveness.

Explaining Differences in Cost Changes / Size is one factor that could logically affect the extent to which rules change. We expected that larger rules would experience larger net changes because their higher costs allow for changes of greater magnitude (e.g., a $1 billion rule should have a greater ability to change by $1 million than a $2 million rule). We also expected that they would have larger percentage changes because larger and more expensive rules should be subjected to more scrutiny by OIRA and outside interests during the rulemakings process. However, there is no evidence to support either of those ideas. Regression analyses do not reveal any correlation between proposed cost and either net or percent change.

One of the reasons given for why larger and more important rules may experience greater changes in cost between their proposed and final stages is that OIRA would subject them to more extensive review. If OIRA subjects a rule to a prolonged review process, it is logical to infer that the delay is due to substantive changes to the rule. But when length of OIRA final rule review is applied as an explanatory variable, it is not correlated with either percentage or net change. There are also no conclusive results if proposed rule length is used.

OIRA is often specifically criticized for reviews that extend beyond the general limit of 90 days. But rules subjected to a final review longer than 90 days actually experienced an average percent change in cost below the overall average. Critics may have other reasons to chastise OIRA for lengthy rule reviews (such as contending that delays expose the public to needless risk), but there is no statistical evidence that OIRA is unduly distorting the cost and benefit calculus of rules by holding them for a longer period.

A Tale of Two Regs / Last year, the EPA released proposed rules regulating “Formaldehyde Emissions” from wood products. The regulations spent more than a year at OIRA and generated plenty of progressive outrage. Georgetown University law professor and noted environmental law commentator Lisa Heinzerling charged that part of the delay may have come from OIRA lowering the purported benefits of the measure. The high-end estimate of benefits decreased from $278 million to $48 million, but some cost estimates also declined slightly, from $89 million to $81 million.

Heinzerling raised questions that have lingered since the existence of OIRA. There is anecdotal, and now comprehensive, evidence of wide variances in the pre- and post-OIRA-review benefit and cost estimates, but little is known about why agencies or OIRA alter such figures.

Another example shows cost estimates falling off the charts, but again little evidence exists to explain the drops. The HHS issued a rule under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), “Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameter for 2014,” that originally had $3.2 billion in long-term costs and more than 10.7 million annual paperwork burden hours. The final payment parameter rule underwent one of the largest decreases in our sample. The number of paperwork hours declined from 10.7 million to just over 1 million, with roughly $3 billion in total costs disappearing. That was caused by the removal of more than 9 billion responses (not a typo) under OMB Control Number 0938–1155. The result lowered annual paperwork compliance from $672 million to just $89 million.

This obviously had profound changes for the overall cost-benefit calculus. At a 3 percent discount rate, the proposed rule would have imposed $529 million in annualized costs during five years. The final rule imposed $70 million in annualized costs. Progressives might complain about the shrinking benefits estimate, but a 750 percent drop in costs also deserves an explanation, especially when the amount of regulatory text codified in the Code of Federal Regulations increased during the rulemaking. Even more puzzling, the final rule produced annual paperwork compliance costs of $89 million, while total annualized costs were just $70 million.

The HHS didn’t offer much guidance in the regulatory text explaining the elimination of the 9 billion responses: “Although we had previously accounted for this estimate as a new administrative cost to issuers in the proposed rule, we are not doing so in the final rule because it is not an incremental cost that issuers will incur as a result of the provisions in this final rule.” That explanation suggests a 9‑billion-response error in the proposed rule analysis, not a radical drop in the requirements imposed by the PPACA rulemaking.

There are likely no “smoking gun” red-line edits from OIRA explaining the changes in the payment parameters rule, but the proposed rule spent only eight days at OIRA and the final rule was under review for 19 days. In fact, the entire rulemaking, from initial review at OIRA to discharge of the final rule, took approximately three months. Economically significant rules can often have a comment period of three months, so perhaps the quick pace of the rule is another cautionary tale to regulators: try to rush rules and the analysis will suffer.

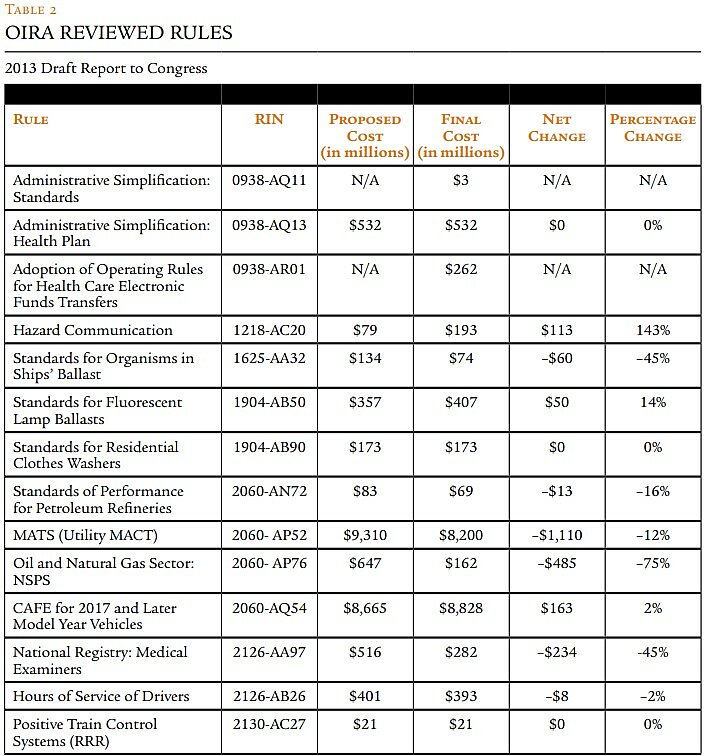

The “OIRA 14” / OIRA listed 14 major rules with quantified costs and benefits in its 2013 Draft Report to Congress. As OIRA attempts to provide an overall picture of the annual rulemaking activity, it is important that those rules accurately reflect the characteristics of the broader set of published rules. Table 2 presents the changes that the major rules underwent during their creation.

The most striking observation from the “OIRA 14” is the general direction of the changes. In the overall data set of rules we examined, roughly half increased in cost; among the OIRA 14, only three did so, while half decreased. The average percentage change for the OIRA 14 is –3 percent, reflecting both the small magnitude and the general negative direction of the changes.

Benefits / Many rulemakings that contain cost estimates are unable to quantify benefits. There were only 14 major rules with both proposed and final benefit numbers in Fiscal Year 2012, so all benefit trends must be viewed in light of the small universe. Seven (50 percent) of the rules had increases from proposed to final, four (28 percent) had decreases, and three (21 percent) had no change—ratios similar to those found for the cost changes. The average net change was a decrease of $2.4 billion, but the median net change was a decrease of just $105 million, suggesting that benefits do not tend to decrease as drastically as initially suggested by the average. The average percentage change in benefits is 14 percent, smaller than the average change in costs (401 percent). The direction of change for benefits is similar to that of costs. Thus, suggestions that OIRA systematically reduces benefits and inflates costs are not supported by this analysis.

Comparing Executive and Independent Agencies / We were able to highlight the effect of OIRA by comparing executive and independent agencies. One of the major distinctions between the two types of agencies is eligibility for OIRA review. Exempting independent agencies from OIRA’s oversight is intended to eliminate a tool the chief executive could otherwise use to constrain their behavior.

The average percentage change in costs for executive agencies was 116 percent. For independent agencies, it was 1,068 percent. The difference is statistically significant at the 90 percent level. Independent agencies tend to increase cost estimates more than executive agencies.

As noted earlier, interpreting the results is made difficult by the inability of the data set to account for why the rules’ figures are changing. One possibility is that OIRA review prevents executive agencies from adding new and expensive sections to their rules after the proposal stage.

More likely, the mandatory analyses that executive agencies must conduct before submitting their proposals for OIRA review, especially when creating a “major” rule, require the agencies to collect more substantial information earlier in the process. Therefore, their original cost estimates reflect a more rigorous and complete consideration of the rule’s effect, making them less susceptible to major alterations because of new information. Also, if independent agencies do not conduct a full cost-benefit analysis at the time of a proposed rule, but add a more complete accounting of the rule’s effect by the final stage, the delayed analysis will result in dramatic increases.

Thus, even if OIRA does not directly constrain executive agencies from making their rules more complex and costly, it may influence their behavior by forcing them to gather more information in the initial stages of rulemaking. Causing cabinet agencies to be more aware of the probable consequences of their decisions should lead them to craft better regulations by choosing the least burdensome alternative to achieve the regulatory end.

In addition, there is value in proposing an initial cost-benefit analysis. It enables the regulated parties to begin to develop expectations about the economic effect of the new rule and to provide more informed input on compliance costs, because they are aware of what the agency is and is not considering. By omitting the initial analyses, independent agencies hinder the ability of the public to understand the costs of the regulation and discuss its consequences.

Conclusion / Rules tend to increase in estimated cost between their proposed and final stages. Benefits are equally likely to increase, but the percentage change in benefits tends to be smaller than the percentage change in costs. This analysis finds that benefits and costs increase in similar proportions. It challenges assertions that regulatory review only serves to shrink benefits.

Specific subsets of data reveal interesting patterns. The 14 rules included in OIRA’s 2013 Draft Report to Congress are much more likely to decrease in costs and change by a smaller magnitude than the overall sample. In addition, when examined by agency or sector, HHS rules show consistent increases, while financial sector rules tend to increase in a much less reliable fashion. Finally, rules proposed by independent agencies tend to increase in estimated cost almost 10 times as much as those from the executive departments. The disparity speaks to the value OIRA provides in helping cabinet agencies to carefully consider costs and benefits from the outset.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.