In the last two decades, several states liberalized their electricity markets, ending government price-setting. Now, some of those states are considering reestablishing the government’s role through the creation of state-sanctioned power authorities — in essence, government-operated “buyers’ agents” for consumers. This article considers the arguments of power authority advocates from the point of view of the debate in Pennsylvania. The primary reference for the arguments presented here are the hearings held in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 2009 and 2010 on legislation to create a Pennsylvania Power Authority. Much of this article seeks to rebut the arguments advanced at those hearings, as well as highlight contradictory statements made by the legislation’s advocates.

On balance, the arguments for a Pennsylvania Power Authority are flawed. No economic basis for establishing such an authority is readily apparent. Further, the envisioned authority would pose high potential to cause harm to the marketplace, much as the California Power Authority did during its truncated tenure.

What Would It Do?

The Pennsylvania legislation would create a state power authority, or power “agency,” whose main directive would be procurement of (hopefully) low-cost power. The state would first create contracts with any willing industrial consumers as well as all the “default” consumers (residential, commercial, and industrial) in Pennsylvania who choose not to shop for power. Then the state would go to private power plant investors and existing generators and make the other end of the contract with the lowest bidders.

The idea is that, if private investors propose to build a base-load plant that can provide inexpensive power to fulfill the contracts, then they will be able to procure financing to do so because the authority contracts provide them with the assurance of return on their investment. The concept underpinning this approach is that the current market does not allow such investment because of risk concerns on the part of entities that would make the relevant capital available. As Pennsylvania Public Utilities Commission vice-chair Tyrone Christy explained during the 2009 legislative hearings, “because of the uncertainty in where the rates are headed — I mean, they go up and down like the roller coaster — it makes it extremely difficult to finance a capital-intensive power plant.”

Note that power authority advocates do not make an argument specific to electricity markets. Investment in all industries in a market economy is risky. To acquire funds to make such investment, an investor must either use his own money or acquire equity or debt funding from other parties. Those parties will seek assurances that they will have an opportunity to gain a reasonable return on their investment. Indeed, such challenges can be seen as a benefit of market economies, in contrast to investment made by government entities that have no such assurances. Put another way, and borrowing a term from commentary on computer software, this restriction on investing is “a feature, not a bug” of the competitive market system. This is in contrast to regulated markets with government-guaranteed investment, which have been shown in electricity markets to lead to huge cost overruns that were eventually paid by electricity consumers.

Once the contract is made, the voluntarily entering industrials will not be able to opt out, but the “default” consumers would be able to choose a different provider at any time. If created, the state agency would be overseen by a five-member board with representatives of small business owners, agriculture, industrials, consumers, and an appointee of the governor.

The envisioned Pennsylvania Power Authority would have the ability to issue its own bonds and build its own facilities. This option appears intended as a sort of “last resort.” However, given the obstacles the authority would likely encounter in getting independent generators to build new plants, use of this financing power might well be required for the authority to fulfill its mandate.

Authority advocates contend that such actions would lead to developing generation facilities that would sell electricity at prices below current market levels. Thus, Christy asserted during the 2009 hearings that “competitive solicitations for the construction of new power plants … would provide power at [lower] contract-based rates rather than at prices that are the product of PJM markets.” (PJM is the regional wholesale electricity market that supplies power to areas of the Mid-Atlantic and Upper Midwest, including Pennsylvania.) This argument appears to ignore the important role of opportunity cost in markets. In this instance, any producer seeking to sell power to a Pennsylvania Power Authority would always have the alternative of selling its power into the PJM market. Thus, there is no reason to believe a Pennsylvania Power Authority could obtain lower prices than those available through the PJM power market.

Indeed, Joe Nipper of the American Public Power Association described in the 2009 hearings how opportunity costs govern current procurement in PJM. According to Nipper, “power supplies purchased by investor-owned utilities used to provide ‘standard offer service’ [are] typically purchased through auctions for relatively short-term contracts [of] two to four years. But the prices offered under these contracts are frequently based on forward projections of the prices likely to be recovered in the PJM spot market.” Thus, according to Nipper, it is opportunity costs that will drive the prices offered in any attempts to gain power through contract. This, of course, is exactly what is to be expected in a market economy.

Did Restructuring Fail?

The initial argument made by power authority advocates is that restructuring has “failed.” This is based on studies (see, for example, Blumsack et al., 2005) that claim that electricity prices are higher in restructured states than in regulated states. However, higher prices alone do not demonstrate failure and this argument is misleading.

First, it is necessary to understand that restructured states did not randomly choose to change their electricity markets. Rather, states chose to restructure because they had high electricity prices to begin with, and were searching for a way to lower those prices. Thus Tennessee, which has the good fortune of having ample low-cost hydroelectric power, is unlikely to choose to restructure. Given this, all other things being equal, restructured states are likely to have less resource endowments, and therefore higher electricity prices.

Second, the relevant studies measured prices during a period of rising energy costs (1998–2008). In restructured markets, prices represent contemporary costs. In regulated markets, however, “regulatory lag” occurs. (See, for example, Spulber and Becker, 1983.) What this amounts to is that higher (and lower) costs are spread out over several years. Thus, it is to be expected that cost increases (and decreases) will be passed through more quickly in restructured markets. Indeed, that is one of the virtues of restructured markets: in terms of economic efficiency, customers should pay the costs of the goods they purchase. In regulated markets, however, rate payers paid too little for power in 2008 and are likely to pay too much for power in the next several years.

In particular, proponents claim — without providing evidence — that the PJM day-ahead market is subject to the exercise of market power. As Pennsylvania House Environmental and Energy Committee chair Camille “Bud” George said during the 2009 hearings, “The competitive wholesale power market exists in name only.” George reiterated this claim in the 2010 hearings, saying, “For example, a study conducted by the American Public Power Association found that generators in the PJM earned more than $12 billion – and that is billion with a ‘b’ – in excess earnings over a seven-year period.”

But if PJM is plagued by market power, it is doing so despite heavy oversight. PJM has an autonomous market monitor that is renowned for its independence from PJM management. PJM also engages in active bid mitigation, which means that if a supplier bids in its capacity at substantially above its marginal cost, its bids are rejected and modified.

It appears that George is confusing two different concepts. Certainly it is possible for firms to make money from the exercise of market power. But that is not the only way firms can make money. In particular, firms can make money by becoming more efficient. Indeed, the economic literature is clear that more efficient firms are a great success of electricity restructuring.

Further, it is by no means clear that firms in this market are making extraordinary profits. As Fischer and McGowan (1982) point out, measuring economic profits is extremely difficult. Specifically, whether or not economic profits occur is often obscured by accounting conventions. Lesser (2009) poses a large number of critiques of the report cited by George. In particular, the American Public Power Association study pointed to strong stock market gains by generating firms over the period of restructuring as evidence that those firms were seizing market power. As Lesser notes, however, market competition is not a zero-sum game; in competitive markets, firms can boost profits by becoming more efficient. The increased efficiency results in savings to consumers. Thus, an increase in the value of a stock by no means implies that the customers of the relevant firm are receiving higher prices.

As noted, electricity prices have risen since 1998, at least in part because of the rising cost of fuels used to produce electricity. Thus, the proper way to view electricity prices is to look at them after they have been fuel-adjusted. The data show that fuel-adjusted prices in PJM have fallen 27 percent since 1998. Therefore, restructuring in Pennsylvania can be seen to be highly effective at reducing prices.

Thus, we are now in a position to put the entire story together. Research indicates that restructured plants have grown more efficient. Data also indicate that fuel-adjusted prices have fallen significantly since restructuring. The natural outcome of this is both lower prices for consumers and higher profits for producers.

Thus, what authority advocates’ argument comes down to is the assumption of restructuring opponents that higher energy costs need not be paid by consumers. They assume that customers in regulated states will not have to face the impact of higher energy prices. Of course, that is not what is likely to happen. Rather, these costs will go into the rate base of customers in regulated states. In other words, there is no free lunch. Given regulatory lag, ratepayers in still-regulated states will be paying for higher energy prices for a long time to come. In Pennsylvania and other restructured states, however, these energy costs have already been paid for.

The PJM Single Clearing Price

The PJM day-ahead market is an economic textbook example of how a market should operate. Demand comes from consumers. Supply comes from the bids of suppliers. Market price and quantity come from the intersection of supply and demand. Price equals the marginal cost of supply, which maximizes the sum of consumer and producer surplus. The same price is paid by all consumers, and the same price is received by all suppliers. The market price sends a signal to potential entrants whether or not it is economical for them to enter the market. If the market price is higher than prospective entrants’ average cost, they consider entering. If the market price is below incumbent firms’ average cost, those firms consider exiting (in the long run). All this constitutes Adam Smith’s famous “invisible hand” about the advantages of free markets. Not only does PJM operate this way, but so does every other commodity market in the world. This is literally Economics 101.

Despite this, the proponents of a Pennsylvania Power Authority claim the PJM “single clearing price” market is flawed. As Christie said during the 2009 hearings, “These clearing prices result in Pennsylvania coal and nuclear facilities receiving far more than the actual cost of production.”

In particular, power authority advocates also cite a study by Blumsack et al. (2008) that they contend implies that the PJM single price market increases electricity costs by 2 to 2.5 cents per kilowatt. But this is not what the report in question says. The Blumsack et al. report concludes that restructuring (not PJM) has increased the price-cost margin by 2 to 2.5 cents per KWh. This is not the same thing as saying prices rose. In particular, this result could be caused by (marginal) costs declining through efficiencies, as the research discussed above indicates has happened during restructuring. Further, this study has been subject to severe criticism. In particular, the study only uses data through 2005. Thus, it is not able to explain what happened to restructured markets after the energy price spike of 2008.

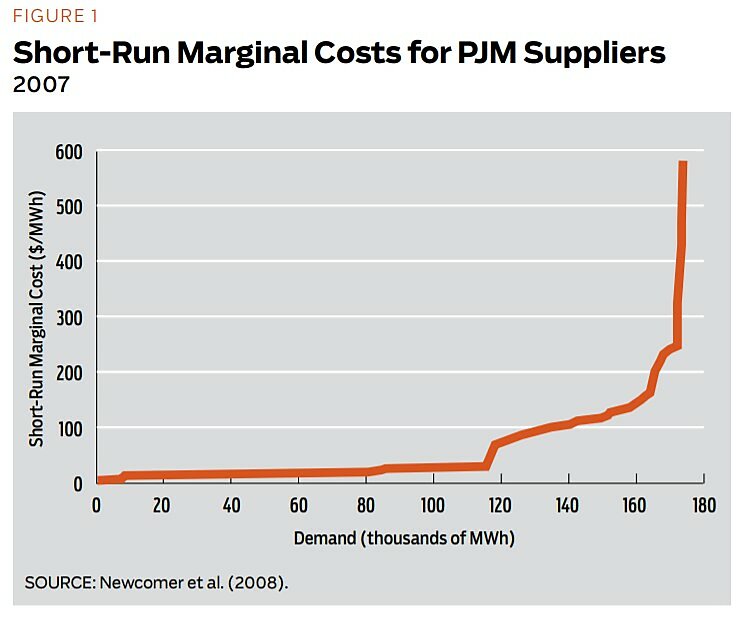

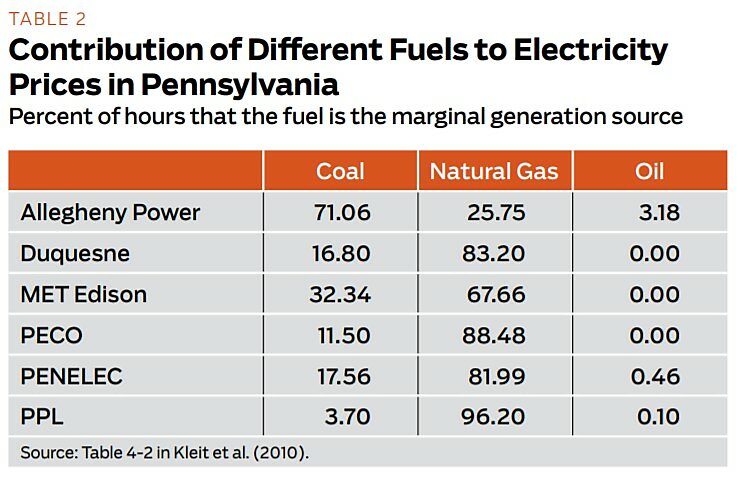

Part of the confusion appears to stem from power authority advocates not understanding the difference between marginal costs and fixed costs. This is especially important in the electricity sector. Baseload plants, such as coal, nuclear, and hydroelectric facilities, generally have low marginal costs and high fixed costs. “Peaking” plants, generally fueled by natural gas, have low fixed costs and high marginal costs. Firms operate their plants when the market price is above their marginal cost of production.

Figure 1 presents the short-run marginal cost curve from PJM, based on the generation stock and fuel prices prevalent in 2007. Note, as is typical with any supply curve, that it is upward sloping. The output on the left comes predominantly from nuclear and hydro facilities. On the right of the graph, with higher marginal costs, are natural gas plants. In the middle are coal plants.

In this context, firms with low marginal costs depend on the market price to cover their fixed costs. Thus, it is necessary for demand (at least some of the time) to intersect with the higher part of the supply curve to keep such plants financially viable. An example of this came up during the 2009 hearings, concerning a proposed expansion of a hydroelectric plant that would have low marginal costs. According to Pennsylvania Consumer Advocate Sonny Popowsky,

[A]t the end of last year, PPL Corporation announced that they were abandoning their plans to add 125 megawatts of capacity to the Holtwood hydroelectric station in Lancaster County on the Susquehanna River.That construction had been planned to begin in 2009, with an expected in-service date of 2012. But in withdrawing their application at that time in December, PPL stated in a press release that, quote, "As we evaluated this project in light of current economic conditions and projections of future energy prices, we reached the conclusion that it is no longer economically justifiable."

Put simply, PPL chose not to continue with the project because the firm expected that the market price of power would not be sufficient to cover the fixed costs of production at Holtwood. Far from a calamity, this was an economically efficient decision.

As stated above, market prices (both spot and long-term) also serve as a signal of whether or not firms should enter the market. In PJM, at this point in time it is clear that the market price is not sufficient to cause entry of coal plants because such entry is not occurring, nor does it appear justifiable given current cost estimates. Thus, the market price serves as an important signal for potential coal entrants: Do not enter this market!

More importantly, however, one needs to understand the background of the restructured industry in Pennsylvania. In 1996, on the eve of restructuring, the state government and the electricity industry entered into a "grand bargain." The state agreed to arrange to have utilities' sunk costs retired in exchange for caps on electricity rates. Thus, Pennsylvania utilities took the chance that they would be able to make profits given uncertain future power prices.

Even if firms are making large profits now, for the state to renege on that bargain would be to offer firms a policy regime of "Heads I win, tails you lose." It would punish firms for the strong efficiency gains they have made in recent years, especially in nuclear power. In addition, it would reduce incentives for further efficiency from existing facilities. Finally, it would send signals to potential entrants that they might not have the opportunity to gain profits in the PJM market because of government action. Such signals would serve to reduce electricity generation investment, increasing prices for consumers.

Long-Term Contracts

The chief argument that power authority proponents have used is two-fold: First, long-term contracts for industrials do not exist. As Christy said during the 2009 hearings, “They [long-term contracts] are just not available in this new regime.” Specifically, proponents like Christy have in mind contracts of 10 to 30 years in duration. Second, such contracts are not available because not “enough” baseload generation has entered the Pennsylvania region.

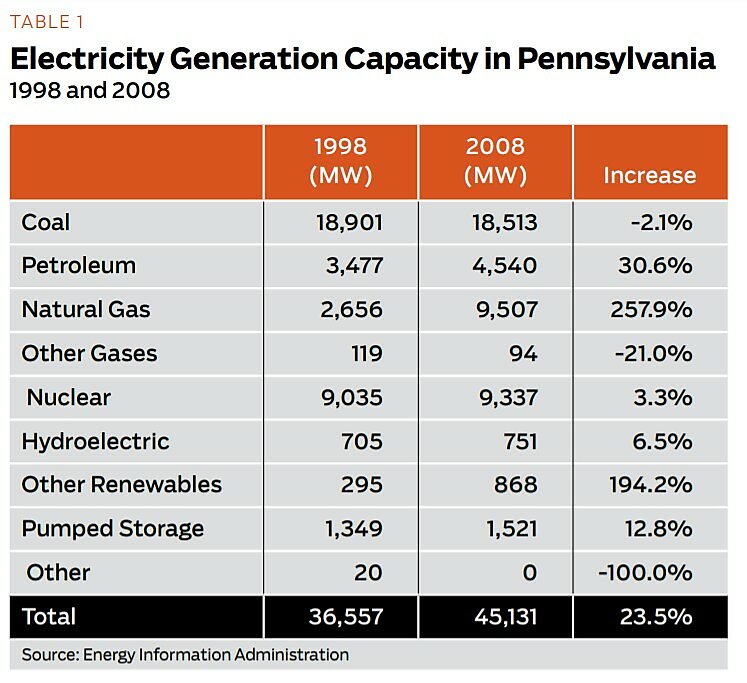

Table 1 describes new entry of electricity generation into Pennsylvania since restructuring in 1998. Since restructuring, generation capacity in Pennsylvania has increased over 23 percent. Baseload capacity, however, has remained stagnant. The majority of the new capacity increases have occurred in natural gas. Natural gas plants are generally run during “shoulder” and “peak” times.

There is nothing fundamentally wrong with this. In particular, at this time, the economics do not support entry of new coal plants, as discussed above. Further, shoulder and peaking plants are very helpful to the electricity system: they aid in reliability issues when demand is high or a particular supply unit is cut off — a problem that will become of increasing importance when increased non-dispatchable renewable energy sources are integrated into the electricity grid.

With respect to coal, however, the above table is misleading. The net change in coal is slightly negative, but this does not imply that there has been no construction of coal-fired generation. It turns out that the coal power supply in Pennsylvania is highly dynamic. Even though the net increase in coal capacity is negative, at least 12,100 MW of new coal capacity has come on line in Pennsylvania since 1998, replacing old coal plants. This new capacity conflicts with the oft-stated claim that restructured markets are adverse to the construction of coal plants.

Power authority advocates assert that non-baseload generators do not affect market price. According to Christie, “Nearly all of the new capacity has either been gas-fired or wind, and for different reasons, neither of these resources is conducive for driving down wholesale power prices in Pennsylvania.” Yet Table 2 indicates this is not the case. In the single clearing price market, as the discussion above indicates, it is the marginal plant that sets the market price. As Table 2 indicates, however, coal is the marginal power unit 70 percent of the time for Allegheny Power, which is in western Pennsylvania. For the other utilities, however, natural gas is the dominant fuel at the margin, ranging from 67.66 to 96.20 percent of the time. Thus, non-baseload electricity generators have an important role in setting prices in PJM. Further, the large entry of natural gas generators has served to decrease PJM prices, as natural gas is “often at the margin” in PJM.

Baseline power typically comes from hydro, nuclear, and coal plants. It is easy to see why more of these plants have not come online. Hydropower is dependent on natural features. While PPL has the opportunity to expand its hydro facilities at Holtwood, there is a limit determined by nature on the amount of hydropower that is available in Pennsylvania. The challenges of nuclear power are well understood. That leaves coal power as the sole opportunity for expansion of baseline generation in Pennsylvania. For the first 10 years of restructuring, thousands of megawatts of coal power capacity came online in the state. Today, however, the challenges for new coal plants are clear. In particular, it is difficult for any firm to commit to build a new coal plant while carbon emission limits are being debated in Congress. Carbon control would imply a tax on the use of coal in producing electricity. In such circumstances, it is quite understandable that firms are not willing to commit to more coal power. Any attempts by a Pennsylvania Power Authority to build coal-fired plants would face the same difficulty.

Given the perceived lack of baseload power, power authority advocates contend that long-term contracts are not available. But this is clearly untrue, as evidenced by the 10-year contract Exelon Corp. entered into in 2009 to supply 200 MW of power to Old Dominion Electric Company. Rather, the perceived problem is that such contracts are not available on terms and conditions that industrial purchasers desire. This becomes clear when examining the testimony of Vic Sawicki, senior energy manager for air products and chemicals for the group Industrial Energy Consumers of Pennsylvania (IECPA). Speaking at the 2009 hearings, Sawicki told state lawmakers,

We want reasonably priced electricity without a lot of volatility. … What we were offered or what we found was that for short-term deals — by that I mean a couple of years, say up to about five years or so — what suppliers were offering was pegged to the short-run market prices or the vision of the futures price. That was the market that we were seeking to avoid. For longer-term contracts, and by that I mean 10‑, 20‑, 30-year contracts, suppliers wanted commitments from individual companies to assume a take-or-pay obligation. And by that I mean that they would want us to be responsible for the capital costs of the facilities from which we were purchasing under all circumstances, whether, for example, one of our facilities that was planning to take the power was in existence or not.

The first option doesn’t get us away from the volatile and high-priced short-term market that we were trying to avoid. It wasn’t a solution for us. The second option presents for us strategic and accounting issues, which I think are likely insurmountable for most of our companies

Prices in a market economy reflect opportunity costs. As Steve Etsler of AK Steel, testifying on behalf of the IECPA during the 2010 hearings, said, “These deals [that industrial customers desired] did not materialize, and the pricing was linked to the expected profit that generation could earn if all of its power were simply sold in the PJM Locational Marginal Price.” This result, of course, is not surprising. Merely because I cannot get a good steak dinner at a local restaurant for $2 does not imply that steak dinners are not available. It simply implies that these dinners are not available on terms that I desire, rather than that terms reflect market opportunity costs. Similarly, merely because long-term contracts are not available on terms industrials desire does not imply that there is any kind of market failure. In this context, it seems that industrial suppliers are simply attempting to purchase inputs without paying the full cost for those inputs.

In particular, it is not surprising that industrial customers could not obtain fixed-term contracts similar to what they received in the pre-1998 regulated era. In the 2009 hearings, State Rep. Scott Hutchinson outlined the problems embedded in such contracts:

On the issue of the long-term contracts, so you got this 10-year contract, and you are the generator, and you won the [contract] and everything was working perfectly. And then my costs of production — I’m the producer — my costs of production suddenly spike and we are losing money. Do we just lose money? Or do rates go up? Or does the state have to cover the difference? You know, I don’t know anybody that can predict what the prices of coal, gas, whatever it is going to be 10 years in advance. Those prices are going to be going up, down, and around during that time. How do you set your 10-year rate? And then what if it doesn’t perform the way you thought it was going to and this utility is absolutely just losing money, and they turn to the state and say, “I quit”?

Representative Hutchinson lays out the problem well. Simply put, there is no accurate way to predict energy prices 10 years or more into the future. For a producer to write a contract with fixed prices for that length of time would be highly speculative. In particular, if energy prices are higher than expected, the producer might walk away from the contract, leaving Pennsylvania and electricity customers on their own.

Put another way, long-term contracts can be considered price “insurance” for customers. Providing any kind of insurance, however, always comes at a cost. Bidders who offer long-term fixed-price service must manage many risks, including volatile fuel costs, unexpected plant outages, weather, customer demand, and so forth. The longer the contracts are, the greater the risks to be managed, and the more costly to insure those risks. In this context, it is not surprising that 10-year and longer contracts may not be viable in the marketplace.

What appears to be happening is that industrial firms are complaining that they cannot get long-term contracts on their own terms. As Blumsack et al. (2008) indicate, in the regulated era, industrial customers were able to get special deals. Thus, industrial support for a Pennsylvania Power Authority may be seen as a method for industrials to once again obtain special rates. Put another way, one advantage of restructuring is it precludes special interests such as industrial firms from gaining favorable rates not available in the marketplace.

Power authority advocates also believe they can eliminate some basic rules of economics. Thus, in the 2009 hearings, Christy claimed that a power authority would receive “competitive solicitations for the construction of new power plants that would provide power at contract-based rates rather than at prices that are the product of PJM markets.” In saying this, Christy appears not to understand that prices are a function of opportunity costs. Put another way, it would be illogical for a producer to offer the authority rates lower than those available in the PJM market.

Effects of a Power Authority

What effects would the creation of a Pennsylvania Power Authority have? The most obvious is that prices would rise. As discussed above, the facts clearly demonstrate that current prices do not support the building of additional coal plants in Pennsylvania. Thus, arranging for a new coal plant would require revenues higher than current market prices. Those higher costs would be paid by consumers.

Second, any power authority–sponsored capacity additions would crowd out private investment. As Table 1 indicates, there have been substantial capacity additions in Pennsylvania since 1998. Such investment, however, is drawn by the opportunity to capture profits for new investments. Those opportunities would be reduced by state-sponsored capacity expansion. Indeed, there is absolutely no reason to believe that electricity capacity sponsored by a power authority would increase total capacity. It would simply “crowd out” market-driven capacity that would otherwise have come online. (See “Gresham’s Law of Green Energy,” Winter 2010–2011.)

Christy has suggested that the envisioned agency would not be subject to the mistakes of other political agencies because its members would be selected from the public, representing various types of consumers. This argument misses the essential critique of politicians and government institutions. Politicians and government actors make mistakes intervening in markets not because they are politicians, but rather because they lack the aggregate information and expertise possessed by market participants and because they do not have the economic incentives of market participants to avoid error. Those problems will not be fully alleviated by requiring that the authority’s board be comprised of citizens from particular consumer groups, rather than politicians.

California preview | Given that it would respond to political rather than market incentives, a Pennsylvania Power Authority could well be expected to repeat the mistakes of the short-lived California Power Authority. The California Power Authority came into being in 2001, on the heels of that state’s electricity crisis. As California faced power shortages and market manipulation driven by a deeply flawed regulatory framework, it chose to enter the market for long-term electricity contracts. As it turned out, the state bought power at exactly the wrong moment, paying well above historical prices for power. Those contracts resulted in litigation, and the State of California did its best to escape the harm of the contracts that it had forged. Nevertheless, the actions of the California Power Authority were very costly for consumers. The California Power Authority was closed in 2006.

Thus, there would be a great deal of opportunity (and incentive) for such an authority to make poor decisions. As Representative Hutchinson explained in the 2009 hearings,

Many of us are very skeptical of the ability of folks sitting in Harrisburg and buying power, building generation plants, with no market check, as it were, on what they are doing, with the consumers on the back end being the ones who are the failsafe, meaning they would be paying for it no matter what happens, especially if you look at what has happened in the last year. You know, if a Pennsylvania Power Authority last summer [2008, during a price spike] had thought, “Well, we better lock in these rates right now because they are only going to go up from here,” and if they had bought 10-year contracts going forward, it would look really foolish [today].

Conclusion

The arguments advanced by advocates of a Pennsylvania Power Authority are deeply flawed. Electricity restructuring in Pennsylvania is not a failure. The single clearing price market used by PJM is a textbook market design, bringing all the efficiencies of Adam Smith’s invisible hand.

Advocates have not made an argument that investment in the state’s electricity generation market face higher burdens than any other market. Indeed, their critiques of investment in restructured markets actually serve to highlight an important benefit of the free market system. Advocates’ arguments even imply that the envisioned contracts would raise the price of power for Pennsylvania consumers.

A Pennsylvania Power Authority may well be designed to serve special interests. It seems more likely to repeat the errors of the California Power Authority by signing contracts harmful to consumers. This seems especially likely if the authority signs 10- to 30-year contracts, as advocates would like.

Readings

- “Bad Economics, by Any Other Name, Is Still Bad: APPA’s Analysis of Wholesale Electric Competition Is Flawed,” by Jonathan Lesser. Continental Economics Briefing Paper No. 2009-08-01, June 2009.

- “Can Electricity Restructuring Survive? Lessons from California and Pennsylvania,” by Timothy J. Considine and Andrew N. Kleit. In Electric Choices: Deregulation and the Future of Electric Power, edited by Andrew N. Kleit; Rowman and Littlefield, 2006.

- “Do Markets Reduce Costs? Assessing the Impact of Regulatory Restructuring on U.S. Electric Generation Efficiency,” by Kira Fabrizio, Nancy Rose, and Catherine Wolfram. American Economic Review, Vol. 97 (September 2007).

- “Does Electricity Restructuring Work? Evidence from the U.S. Nuclear Energy Industry,” by Fan Zhang. Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol. 55, No. 3 (September 2007).

- “Electricity Prices and Costs under Regulation and Restructuring,” by Seth Blumsack, Jay Apt, and Lester Lave. August 2008.

- “Getting on the Map: The Political Economy of State-Level Electricity Restructuring,” by Amy Ando and Karen L. Palmer. Resources for the Future Discussion Paper 98–19-REV, May 1998.

- “Gresham’s Law of Green Energy,” by Jonathan A. Lesser. Regulation, Vol. 33, No. 4 (Winter 2010–2011).

- “Impacts of Electricity Restructuring on Rural Pennsylvania,” by Andrew N. Kleit, Seth Blumsack, and Zhen Lei. Draft report to the Center for Rural Pennsylvania, August 2010.

- “Lessons From the Failure of U.S. Electricity Restructuring,” by Seth Blumsack, Jay Apt, and Lester Lave. The Electricity Journal, Vol. 19, No. 2 (2006).

- “Market Monitoring, ERCOT Style,” by Andrew N. Kleit. In Electricity Restructuring: The Texas Story, edited by Lynne Kiesling and Andrew N. Kleit; American Enterprise Institute Press, 2009.

- “On the Misuse of Accounting Rates of Return to Infer Monopoly Profits,” by Franklin Fischer and John McGowan. American Economic Review, Vol. 73, No. 1, March 1983.

- Power System Economics, by Steven Stoft. Wiley Inter-Science, 2002.

- “Regulatory Lag and Deregulation with Imperfectly Adjustable Capital,” by Daniel F. Spulber and Robert A. Becker. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 6, No. 1 (1983).

- “The Short Run Economic and Environmental Effects of a Carbon Tax on U.S. Electric Generation,” by A. Newcomer, S. Blumsack, J. Apt, L. B. Lave, and M. G. Morgan. Environmental Science and Technology, Vol. 42 (2008).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.