Over the past two decades, the regulatory process in New Jersey has (on the surface) become increasingly complex. State agencies are now required to conduct numerous analyses of their regulations, in the name of greater accountability and transparency. Legislative oversight has been strengthened. Negotiated rulemaking is required in certain circumstances. All of this comes on top of the “notice-and-comment” process that is common to rulemaking in most states and at the federal level.

Have these procedural changes resulted in “better” regulations? Or have they made the regulatory process so cumbersome that agencies have turned to alternative forms of policymaking? Answers to these questions are important for New Jersey lawmakers and agency officials because they could lead to reforms of the state’s administrative process. They are important to officials in other states because they can provide guidance about the wisdom of procedural reforms to the regulatory process (particularly in the wake of a new Model States Administrative Procedure Act issued by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws in 2010). Finally, these questions, which have been debated regarding the federal administrative process, have hardly ever been examined at the state level. A better understanding of state rulemaking may facilitate understanding of the federal rulemaking process.

For this article, we examined 1,707 regulations in New Jersey from the time periods of 1998–1999 and 2006–2007. We collected data on a number of variables capturing the administrative process in New Jersey. Those data include the number of comments received from the public, the length of the rule, agency response to comments, and reproposals triggered by substantive changes. We also did a more detailed examination of the impact analyses of the most controversial rules issued in those four years.

We found that agencies are largely immune to the procedural requirements of the regulatory process in New Jersey. Substantive changes to agency proposals as a result of comments are rare. Impact analyses are pro forma at best. Legislative review has not been used by the New Jersey state legislature to invalidate an executive branch regulation since 1996. The volume of rulemaking is largely unchanged over the past decade despite changes in administration and the addition of procedural requirements.

Studies of the Rulemaking Process

The regulatory process has been the subject of much research over the past few decades. This research has appeared in both law reviews and political science journals. Much of the research has focused on the proceduralization of the rulemaking process.

The requirement that agencies follow a notice-and-comment process when engaging in rulemaking can be seen as the oldest of these procedures. Participation by interested parties in rulemaking predates the federal notice-and-comment process adopted in the federal Administrative Procedure Act, passed in 1946. Many states have since adopted their own versions of this law.

At the federal level, many subsequent procedures have been added to the regulatory process. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan issued Executive Order 12291, requiring both that agencies conduct cost-benefit analyses of certain regulations and that the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs review proposed and final regulations from agencies on behalf of the president prior to their issuance. The Unfunded Mandates Reform Act, passed in 1995, requires consideration of state and local views in regulatory decisions, and the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act requires the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to convene panels of small business representatives to review rules so that they do not unfairly burden small businesses. Many of these procedures have been replicated on the state level, but this varies from state to state.

The role of these procedures is the subject of considerable academic debate. Matthew McCubbins, Roger Noll, and Barry Weingast (often referred to as “McNollgast”) highlighted the role of procedures in political control of bureaucrats more than 20 years ago. According to the theory articulated by McNollgast, when Congress creates or empowers a bureaucratic agency, it creates a certain procedural environment. This environment, Congress hopes, will ensure that the interests represented by the enacting coalition remain in a favorable position with respect to agency decisions. Congress creates these procedures to attempt to insure against coalitional drift (changes in political power) and agency drift (bureaucrat preferences that differ from those of political principals).

The hope among enacting coalitions — the political actors creating the procedural control — is that this “deck stacking” ensures that the bureaucracy implementing a statute faces the same environment as the coalition enacting the statute. Therefore the bureaucracy will make future decisions according to the preferences of the enacting coalition.

The notion that procedural controls severely constrain the decisions of bureaucrats and future politicians has received a fair amount of criticism. Notably, Murray Horn and Kenneth Shepsle argue that those implementing procedural controls ignore the tradeoff between coalitional and bureaucratic drift. A control that will successfully stifle bureaucratic discretion will be unable to prevent changes in policy by a new legislative coalition, and vice versa. In other words, enacting coalitions may be able to control bureaucrats, but the mechanisms that these coalitions create to do so will be in the hands of future political coalitions who may be hostile to the aims of those who created the procedures.

Others have argued that procedural controls were likely to have a uniformly deleterious effect on regulatory decision making. Thomas McGarity coined the term “ossification of the regulatory process” to refer to the purported impact of judicial review and analysis requirements (two procedural controls), which in turn would make writing regulations so difficult that agencies would turn away from the regulatory process. According to McGarity and others, once an agency has written a rule, the agency is, as a result of procedural requirements, unlikely to change it, and in some cases the new requirements may deter agencies altogether from using rulemaking as a policy device. They worry that the costs of rulemaking have increased to the point where it may no longer be worthwhile for bureaucrats to undertake the effort associated with rulemaking. This argument has entered the political lexicon, often described as “paralysis by analysis.”

Recently there has been more work on state regulatory processes, but still much less examination than on the federal level. Jim Rossi has called for greater attention to administrative law on the state level. Richard Whisnant and Diane De Cherry examined the use of cost-benefit analysis in North Carolina. Several articles rely on surveys of agency officials that asked about their perceptions of influence from the political branches of government and interest groups. In a 2004 article, Neal Woods found that agency officials perceived gubernatorial oversight as more effective than legislative oversight. Woods also used the survey data to conclude that provisions broadening access and notification to the rulemaking process increased the perception of influence of outside actors, particularly the courts and interest groups.

A number of articles have focused on legislative review on the state level (perhaps because such a procedure is absent at the federal level). The literature shows mixed results for the effect of legislative review. An article in the Harvard Law Review examined legislative review in Connecticut and Alaska and showed that it did result in changes of agency regulations. Marcus Ethridge examined legislative review in three states and found that stricter rules were more likely to be reviewed. Finally, Robert Hahn examined both economic analysis and legislative review and found many requirements, but little evidence that the requirements had improved regulatory outcomes.

From the literature on both the federal and state rulemaking processes, the evidence that procedures make a difference in substantive outcomes is limited. Some scholars see public comment as being important, but others do not. Few have found that legislative review and economic analysis make a substantive difference. Yet these procedures continue to be implemented at the federal and state levels. The evidence that procedures have led agencies away from rulemaking is also very limited.

What role do procedures play in the rulemaking process? If they had a substantive effect, we would expect to see some of that effect. Procedures that encourage participation should lead to more participation and perhaps more acceptance of the suggestions made by participants. Procedures that require analysis should lead to analyses being conducted and rules that are less costly. Procedures for legislative or executive review should lead to rules that reflect the preferences of those political branches and occasional vetoes of the rules that do not. If, instead, the procedures deterred agencies from engaging in rulemaking, then we would expect fewer rules.

The analysis here is best read as a case study of the history and effects of regulatory reform in a single state. We feel that New Jersey is an excellent case study because of the sheer volume of regulatory reforms that the state has undertaken over the past few decades. By doing a detailed examination of rulemaking in New Jersey, we hope to shed light on the role of procedural controls. By highlighting the impact of procedures (or lack of impact) in one state, we hope to clarify questions about procedural controls in other states and in the federal government.

As we will describe, we collected a large set of data on rulemaking in New Jersey and interviewed several knowledgeable participants in the New Jersey regulatory process. Together, this information largely supports the empirical work on the federal level that has cast significant doubt on the idea that procedural controls play a major role in regulatory decision making.

Recent History of Rulemaking in New Jersey

Since the New Jersey Administrative Procedure Act was enacted 40 years ago, the state’s regulatory process has received intermittent attention by public policymakers. The lion’s share of the procedural reforms has been added over the last 20 years. Overall, the modifications that have occurred cannot be traced to partisan leadership. While four of the initiatives were signed into law by Republican governors, half the measures were advanced during sessions led by legislative leaders of the opposition party. The reforms also evolved through fits and starts rather than through broad mandates or public support.

The rulemaking changes made in the 1980s and 1990s attempted to minimize the effect of regulations on small businesses, farmers, the job market, and the economy in general. Adding to existing proposed rule requirements (social and economic impact statements) was the inclusion of a Jobs Impact Statement, which quantifies the number of jobs lost or created by a proposed rule. Moreover, for rules affecting businesses with fewer than 100 employees, a Regulatory Flexibility Analysis is required that describes any methods utilized to minimize the adverse economic impact on small businesses from recordkeeping, reporting, or compliance requirements. Another provision calls for a Federal Standards Statement that requires an agency to address whether a proposed rule exceeds federal standards. In the case when a federal standard will be exceeded, the agency must include a cost/benefit analysis supporting its decision.

At the same time that these analysis requirements were being put in place, attempts to establish enhanced oversight of regulatory agencies were also taking place. The legislative branch in New Jersey enjoys strong constitutional powers; however, legislative veto authority over regulations was not included in the revisions made at the state’s 1947 constitutional convention. The combination of two branches with strong constitutional powers, along with a partisan divided government from the period of 1981–1992, set the stage for a rulemaking turf battle.

The 1981 bipartisan passage and subsequent override of then-governor Thomas Kean’s veto of a measure that authorized the legislature to approve or disapprove all rule proposals during his first term was short-lived. By the summer of the following year, the state Supreme Court struck down the New Jersey Legislative Oversight Act as unconstitutional because it violated the separation of powers under the state constitution. The legislature kept working to gain power in regulatory oversight. Ultimately, a second ballot question granting legislative veto authority was again presented to the voters for approval in 1992 and passed by a wide margin.

The regulatory process in New Jersey was substantially revised in 2001. Among the key components was increased transparency, including the publication of all agencies fees, penalties, deadlines, and processing times, as well as a more widely disseminated public notice requirement and required agency compliance to a quarterly rulemaking calendar. The changes also broadened public hearing requirements and allowed extensions to the comment period when sufficient public interest warrants. The law enhanced the petition process by setting strict deadlines for agencies to respond, limiting agency discretion in the manner it responded, and providing intervention by the Office of Administrative Law in the event the agency failed to comply. Since the 2001 law was enacted, no new changes to the regulatory process have been adopted.

Our Data

In order to provide a contextual view of rulemaking activity over the past decade, we gathered aggregate data from 1998 through 2007. The data included all rulemaking activity subject to the New Jersey APA from a notice of pre-proposal, notice of proposal, and notice of adoption. We also collected data on a number of rule adoption variables for the years 1998–1999 and 2006–2007. The variables measured included the type of rulemaking activity, agency, whether full text was published, page length of rule, public comment entered into the record, total number of individuals who submitted written comments or signed a petition (if individually recorded by the agency), whether a public hearing was held as part of the public comment period, and if a hearing was held, the number of individuals who attended. Finally, total public participation was calculated and the agency response was recorded. We also did a more detailed examination of the impact analyses of the most controversial rules issued in these four years.

The four years for which we gathered longitudinal data represented a two-year period during a Republican-led administration (Christine Todd Whitman) and a Democrat-led administration (Jon Corzine). For each of the cycles, the legislative leaders in both chambers shared the same party affiliation as the governor. The years studied occurred closely before and after the enactment of the substantial procedural reforms adopted in 2001. We hoped this would help us assess the effect, if any, that changes to the procedural requirements have had on the regulatory process in New Jersey.

In our analysis, we include only those rules that make a change to policy. Finally, to improve the depth of our understanding of New Jersey rulemaking and the role of procedures, we conducted six interviews with frequent participants in the regulatory process. These included individuals with experience in agencies as well as in outside groups with an interest in regulatory issues (and some of the individuals had both inside and outside experience with rulemaking). After asking the interview subjects about the history of their involvement with rulemaking, we went though the procedures we were interested in (notice-and-comment, analysis, legislative review, and regulatory negotiation) to obtain their experiences and perceptions.

Our Findings

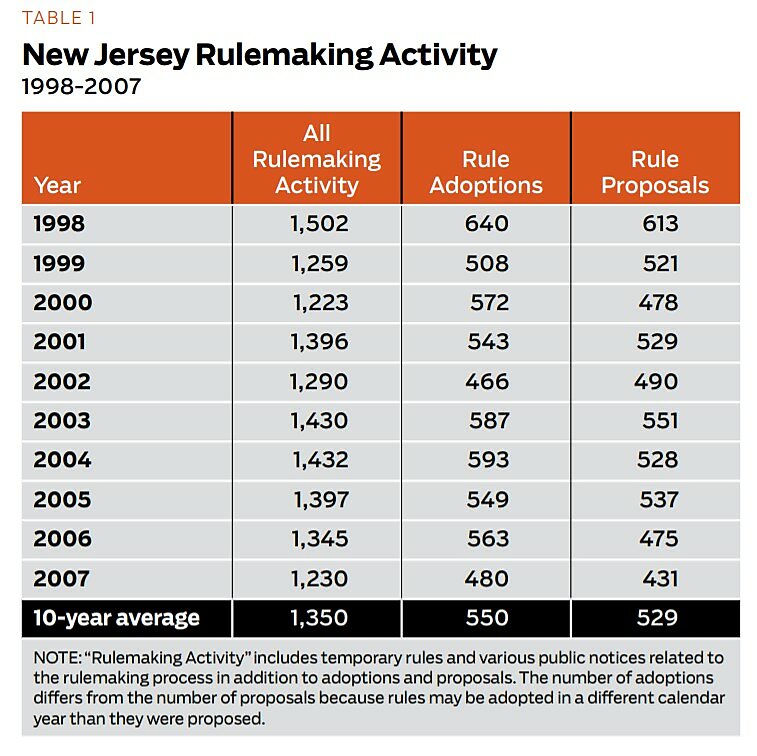

A historical overview of the 10 years of our study reveals that the volume of rulemaking activity has remained relatively steady in New Jersey. On average, annual rulemaking activity over the period is 1,350 rules per year. It is difficult to distinguish any party preference for regulations based upon the summary data, shown in Table 1. The average number of rules proposed and adopted under a Republican administration (1998–2001) closely track that of two Democratic administrations (2002–2007). Although rule adoptions appear to have spiked in 1998, that number results from a high proportion of new rules that were triggered by expired regulations and one-time processes such as traffic control signalizations and drug formulary additions and deletions.

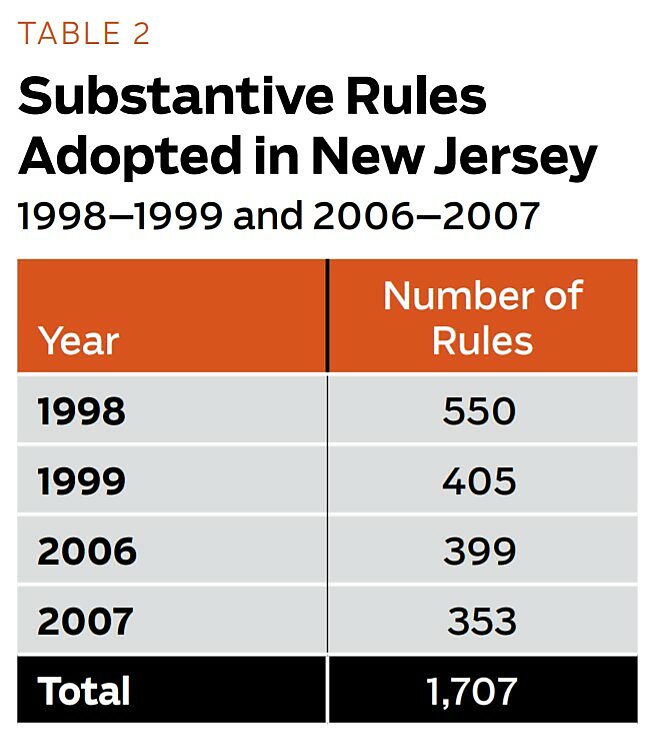

As discussed above, we looked at four calendar years in greater detail. We chose 1998–1999 and 2006–2007 in order to examine two years when New Jersey was under Republican leadership and two years when it was under Democratic leadership. We then culled the dataset to include only those final rules that made substantive changes to public policy (eliminating many of the routine rules issued by state agencies that are not related to policy changes). The number of rules we ultimately examined is shown in Table 2.

As discussed above, there was a greater number of rules in 1998 because two departments had increased new-rule adoption activity and adopted amendments, namely the state’s Department of Transportation and the Department of Health and Senior Services. The spike in 1998 is particularly due to the number of adopted amendments for those two departments: Transportation had 60 and Health and Senior Services had 40. Many of the Transportation rules dealt with traffic signalizations and many of the Health and Senior Services rules covered drug formularies. This type of rulemaking — traffic operations and drug utilization reviews — were not found in any significant number in the 2006 and 2007 years, further explaining the atypical volume in 1998.

Once this anomaly is corrected, we see a slight decrease in rulemaking between 1998–1999 and 2006–2007. This raises the question, if the volume of rulemaking did not change much, did the procedural reforms have other effects?

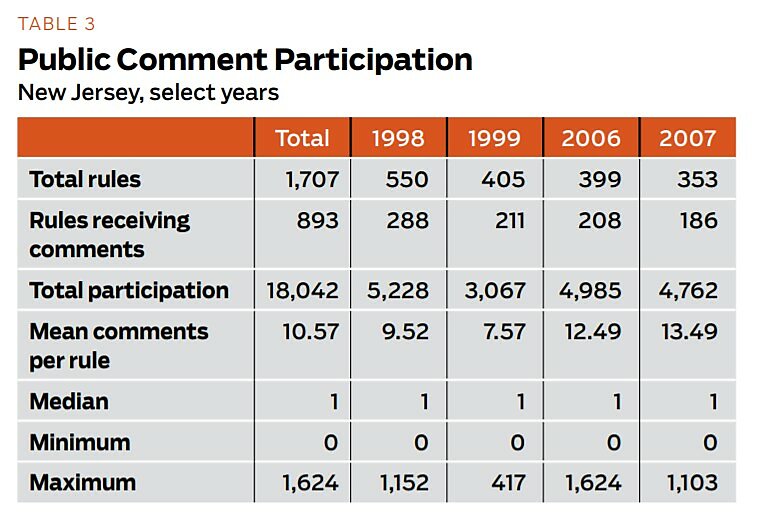

Public input | At the very center of all rulemaking activity is the public participation process. Yet, the volume of input and output as measured by public participation during the comment period and by agency changes made after a rule proposal suggests only a modest impact on the overall process. To begin, half of the 1,707 rules adopted (51 percent) received public comments during the study period. For 1998, 49 percent of adopted rules were commented on by the public, 50 percent in 1999, and 52 percent in both 2006 and 2007. The number of comments for any given rule ranged from 1 to 1,624; about half of the rules that received comments (53 percent) received two comments or fewer. The mean number of comments received per rule was 20.06; however, this average is misleading because of a skewed distribution — the median is 2.25. Thirty rules received over 100 comments, which amounted to 68 percent of the total comments submitted (11,809). If you adjust for this skew by eliminating those 30 rules that received 100 or more comments, the average number of comments received on the most significant rules adopted was just 3.34; the median was 0. This difference between the mean and median also occurs at the federal level and reflects the tendency of a few rules to generate most of the comments from the public.

Did participation increase after the procedural reforms of July 2001? Recall, the key components included a more widely disseminated public notice requirement, agency compliance to a regular quarterly rulemaking calendar, extended public comment periods, and a public hearing requirement when and if sufficient public interest warranted, as well as the maintenance of a verbatim record of the public hearing.

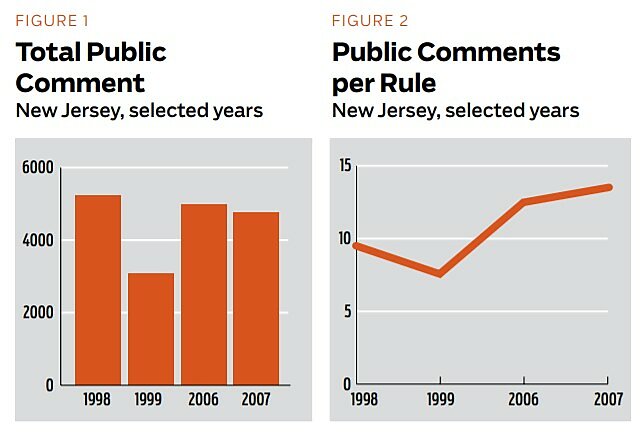

The number of rules that received comments was nearly identical in the four years. It appears that participation, as measured by the number of comments either written or oral, actually declined slightly between 1998 (5,228) and 2007 (4,762) of the study period, as displayed in Figure 1. Still, if this number is divided by the number of rules adopted, the resulting quotient increased from 9.51 in 1998 to 13.49 in 2007, as shown in Figure 2. No change in format submission has occurred to explain the percentage increase; all comments must still be submitted to the regulating agency in writing rather than electronically. What changed is the publication and distribution of the rulemaking calendar.

The 2001 reforms may be responsible for the increase in the number of comments per rule. It is also possible that because of the proliferation of email, interest groups have become more capable in terms of organizing their membership during the public participation process. Additionally, while the mean number of comments has increased, the median remains 1 for all study years, as shown in Table 3. This indicates that the increased participation per rule is the result of large participation in a small number of rules. Because our ability to examine the affiliation of commenters is limited, we cannot determine the extent to which the increase in comments is due to increased interest group mobilization.

Responsiveness to public input | We also assessed the end of the rule-adoption process to determine the effect public participation had on rules. As noted earlier, all rules have to be adopted within a year of the proposal publication; if not, the proposed rule would expire. Additionally, if substantive changes are proposed, the rule needs to be reproposed. We examined the number of notices of reproposal for the entire 10-year period. We found less than two percent of all rule proposals were substantively changed, requiring a reproposal. The mean for the 10-year period was 8.3 rules and the median was 8, with a range of 5 to 16. Once again, the data indicate a limited impact for public comments and a limited change over the time examined.

One agency official explained this to us:

We consult with stakeholders as we draft regulations and many changes are made in draft rules before we formally propose a rule amendment. Therefore we don’t often need to make substantive changes once a rule has been officially proposed.

This agrees with William West’s observation that many rulemaking decisions are set before a proposed rule is even issued.

Still, changes can be made to a rule without a reproposal if the changes do not “effectively enlarge or curtail the original proposal, change its effect, or those who will be affected.” Of the 1,707 rules we examined, only 477 (28 percent) were changed by the agency after the rule was proposed. By comparison, there was also a slight decrease in the percentage of agency changes made in the latter study years, despite the procedural changes implemented in 2001 to broaden public participation. Twenty-nine percent were made in 1998 and 30 percent in 1999, as compared to 25 percent in 2006 and 27 percent in 2007. We have no hypotheses explaining this decrease, but it is interesting that after the changes to broaden participation in 2001, agencies changed rules less frequently.

Given the small percentage of changes made following the public participation period, we examined the agency responses to comments in the most controversial rules issued in the four years we studied closely. In the 30 rules in these four years on which agencies received 100 or more comments, there were only three rules on which agencies seemed to make meaningful changes. This small percentage further indicates that the effect of public comments is limited.

Finally, a number of our interview subjects specifically voiced frustration with agency responsiveness. “While the agency generally wanted to be responsive to public comments, there was a strong incentive to adopt rules without substantive changes, as republication of the revised rule was required under the APA,” said one. Another said, “In my history, I remember few if any actual changes of substance made in response to comments.” The reproposal requirement clearly acts as a disincentive for agencies to make changes in response to public comments. One respondent suggested modifying the APA to allow agencies to make changes without wholesale reproposal.

Impact statements | In New Jersey, agencies have been required to conduct some form of impact analysis on their rules since 1981. As with our analysis of agency changes to rules, we examined the impact statements of those rules with at least 100 comments. We believed that those rules with the most comments were likely to be the ones with the largest economic impacts. Of the 30 rules with more than 100 comments, only four had impact statements that contained actual numbers to describe the economic effect of the regulation. Two of the rules were issued by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. One on protecting highlands water had a detailed analysis of the economic impact. A second rule protecting horseshoe crabs had information on fish catches and the tourism industry, but did not have a conclusion about the economic impact. A third rule on a surcharge on goods sold in prisons described the total revenue that the agency expected to generate (not an impact per se). Finally, a rule on Medicaid reimbursements for nursing homes similarly totaled the expected budgetary effects without a meaningful assessment of economic impacts.

The remaining rules either had a brief qualitative discussion of economic impacts or simply asserted that there would be no impact. An example of a qualitative discussion could be found in a rule prohibiting certain trucks from certain state roads:

Double-trailer truck combinations and 102-inch wide standard trucks not doing business in New Jersey will be prohibited from using state highways and county roads as through routes or short cuts. This may have a negative impact on those truckers and shippers since it may take longer to arrive at their destinations, thus making it more costly, or it could cost more in tolls compared to some parallel routes.

With such cursory attention given to economic impacts, it is hard to argue that the requirement for an impact analysis has had much of an effect in New Jersey. This impression was reinforced by the interview subjects who uniformly minimized the role of analysis, with one saying, “I would have to say that the required analyses played a relatively small role.” Instead, the pattern seems to be an even starker example of what some scholars have said occurs at the federal level: impact analyses seem to be written after the rule is formulated, to justify the rule, rather than used to influence the regulatory decision being made.

Legislative oversight | The procedural change with the potential to have the greatest impact on rulemaking emanates from the state’s constitutional provision that grants legislative oversight. Although the legislature has had veto authority over rules for the past 16 years, it has rarely exercised the power. On occasion, concurrent resolutions have been sponsored by members of the legislature, but the number introduced has averaged around 13 per session over the last 12 years. During that timeframe, three concurrent resolutions were passed by both chambers, which served 30 days’ notice on the agency to amend or withdraw the existing or proposed rule or regulation. In each case, a second concurrent resolution invalidating or prohibiting the rule or regulation did not follow.

Discussion

The data on the New Jersey rulemaking process reinforce the theme of consistency through procedural and political changes. Agencies march on, writing regulations regardless of their political or procedural environment. Political changes in the governor’s office and the state legislature seem to have little effect on the pace of regulation, though there may have been substantive effects (e.g., regulations may have been deregulatory under Republican administrations).

For administrative law scholars, the limited effect of regulatory procedures may be of even greater interest. Most notable are the limited circumstances in which agencies change their proposals as a result of public comments. Fewer than two percent of all rules are reproposed, the most significant category of changes. Of the remaining rules, very few have anything but the most minor changes. This is true even for those rules receiving more than 100 comments.

Requirements for various types of analysis also appear to be epiphenomenal. Of the analyses examined in this dataset, very few had actual numbers, and even fewer (one, by the estimation of these authors) measured true economic impact. The impact of economic analysis requirements appears to be even more limited than similar requirements at the federal level. In fact, the impact analyses appear to be little more than superficial window dressing in the regulatory preamble.

Other regulatory procedures are similarly limited. Legislative review has resulted in only three rules being challenged over the last 12 years. The one procedural change that may have had an impact is the 2001 efforts to increase public participation, but even that change had large effects only on the most controversial rules and may be due to more effective interest group mobilization rather than the change in regulatory procedures.

Regulatory reformers at the state and federal levels should take note: procedural control of bureaucratic agencies is unlikely to be particularly effective, if the New Jersey example is representative. Indeed, political control of agencies may even be particularly challenging. Delegations of rulemaking authority to unelected officials, once given, are hard to rescind or control afterward.

Readings

- 52 Experiments with Regulatory Review: The Political and Economic Inputs into State Rulemaking, by Jason Schwartz. Institute for Policy Integrity, 2010.

- “Administrative Procedures as Instruments of Political Control,” by Matthew McCubbins, Roger Noll, and Barry Weingast. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, Vol. 3 (1987).

- “Consequences of Legislative Review of Agency Regulations in Three States,” by Marcus Ethridge. Legislative Studies Quarterly, Vol. 9 (1984).

- “Cost Benefit Analysis: Legal, Economic, and Philosophical Perspectives: State and Federal Regulatory Reform: A Comparative Analysis,” by Robert Hahn. Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 29 (2000).

- “Economic Analysis of Rules: Devolution, Evolution, and Realism,” by Richard Whisnant and Diane De Cherry. Wake Forest Law Review, Vol. 31 (1996).

- “Formal Procedures, Informal Processes, Accountability, and Responsiveness in Bureaucratic Policy Making: An Institutional Policy Analysis,” by William West. Public Administration Review, Vol. 64 (2004)

- “Overcoming Parochialism: State Administrative Procedure and Institutional Design,” by Jim Rossi. Administrative Law Review, Vol. 53 (2001).

- “Political Influence on Agency Rule Making: Examining the Effects of Legislative and Gubernatorial Rule Review Powers,” by Neal Woods. State and Local Government Review, Vol. 36 (2004).

- “Promoting Participation? An Explanation of Rulemaking Notification and Access Procedures,” by Neal Woods. Public Administration Review, Vol. 69 (2009).

- “Some Thoughts on Deossifying the Rulemaking Process,” by Thomas McGarity. Duke Law Journal, Vol. 41 (1992).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.