For years, congressional Republicans have sought unsuccessfully to pass the Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny (REINS) Act. While various iterations of the bill have been proposed, the fundamental principle remains the same: Federal executive branch agencies may not implement major regulations meeting a minimum economic threshold without first obtaining congressional approval.

Proponents of the bill point to the accumulation of federal regulations in recent decades stemming from Congress’s broad delegation of regulatory authority to federal agencies. While delegation has the potential advantage of allowing subject matter experts within the agencies to work with the regulated community and craft nuanced regulations, it is believed to come at the expense of political control. Proponents say the REINS Act would stem the tide of new regulations by enhancing congressional oversight and strengthening accountability for major new regulations.

Those critical of the REINS Act believe it is a recipe for inaction, further burdening the work of Congress with regulatory review while delaying the implementation of needed regulations that can improve public health or safety. Some of these critics say it would supplant expert judgment and politicize the regulatory process. Others question its effects on the proper separation of powers between the executive and legislative branches of government.

Given the absence of a federal REINS Act, arguments for and against it are theoretical. However, we can glean insight into its effects from the states, where many legislatures require some form of legislative approval of regulations. Broughel et al. 2022 report that 43 states have legislative review of regulations, though there are variations with respect to which rules are reviewed, by whom, and what actions the legislature may take regarding regulations. In some cases, state legislatures may veto a new regulation; other states require affirmative legislative approval prior to a regulation taking effect.

This article examines one state’s experience with legislative review. Idaho has required legislative approval of regulations for decades. It uses publicly available reports from the Idaho Office of Administrative Rules Coordinator to determine the effects of legislative review on the rejection rate of proposed regulations and the workload of legislative committees. This experience should inform the debate over the REINS Act at the federal level.

An Overview

Idaho is a supermajority Republican state. For this article’s study period of 2010–2019 (after which a policy change complicates further analysis), the state had two Republican governors, though the timing of the transition was such that all examined regulations were promulgated under the first of those administrations. The Idaho House of Representatives and Senate both had supermajorities of Republicans in each year, with the party holding roughly 75–85 percent of seats in the House and 80–83 percent of seats in the Senate.

Idaho has a part-time legislature that meets annually, commencing in January. While there is no defined time limit on legislative sessions, Idaho sessions typically run 75–90 days. Within this period, the legislature considers gubernatorial appointments, sets the state budget, considers legislation, and reviews proposed regulations, among other duties and customs.

The Idaho Administrative Procedure Act (APA) sets forth the legislative review rules for regulations adopted by agencies that have been delegated rulemaking authority. For the study period, rulemaking was highly decentralized, with 61 different entities promulgating at least one docket of regulations that was submitted for legislative review. These entities include cabinet-level departments, appointed boards, quasi-governmental commissions, and constitutional officers who are elected separately from the governor.

Idaho initially adopted its APA in 1965 and did not include legislative review, but a “relatively coarse form” of review was added in 1970. Various APA amendments and court cases have refined Idaho’s legislative review of rules throughout the years, along with the adoption of a voter-approved constitutional amendment in 2016 that enshrined the legislature’s power to review rules to ensure they are consistent with the intent of the legislature.

Idaho now has three primary forms of legislative review of regulations:

- Interim Review of Proposed Regulations: When an agency publishes a proposed rule outside of a legislative session, certain information is provided to a legislative joint subcommittee. The subcommittee is comprised of members of the germane standing committees from both the House and Senate that the regulation will eventually be referred to for final review during legislative session. This step essentially puts the legislature on notice that the regulation is in the works and lets the subcommittee request certain information from the agency (e.g., an economic impact statement) or file an objection to the proposed regulation with the agency. This authority is rarely invoked by the legislature, and committees traditionally wait until the legislative session to weigh in on pending regulations.

- Approval of New Regulations: Each pending regulation is referred to the germane standing committee in both the Idaho House and Senate for review. The Idaho APA states that the legislature “shall” review such rules, and that they may be approved or rejected by a concurrent resolution of the legislature. The Idaho APA specifies that the basis for review is to “determine if the rule is consistent with the legislative intent of the statute that the rule was written to interpret, prescribe, implement, or enforce.” Germane committees spend several days or weeks reviewing pending regulations in public committee meetings. State agencies are invited to present their pending regulations and answer committee member questions. Public testimony is sought and any interested party may provide input to the committee. Regulations may be rejected “in whole or in part,” and those that are rejected by the committee do not take effect. Regulations that are approved by concurrent resolution take effect upon the date established by the legislature in the resolution.

- Oversight of Existing Regulations: Germane standing committees may review an existing regulation at any point in time and reject those deemed inconsistent with legislative intent via concurrent resolution. This authority is rarely invoked, and the legislature primarily spends its time focused on reviewing new regulations. Recently, the legislature established a periodic review schedule whereby each existing regulation will be reviewed every eight years. This periodic review will commence in 2026, with approximately one-eighth of all existing regulations reviewed annually on a rolling basis.

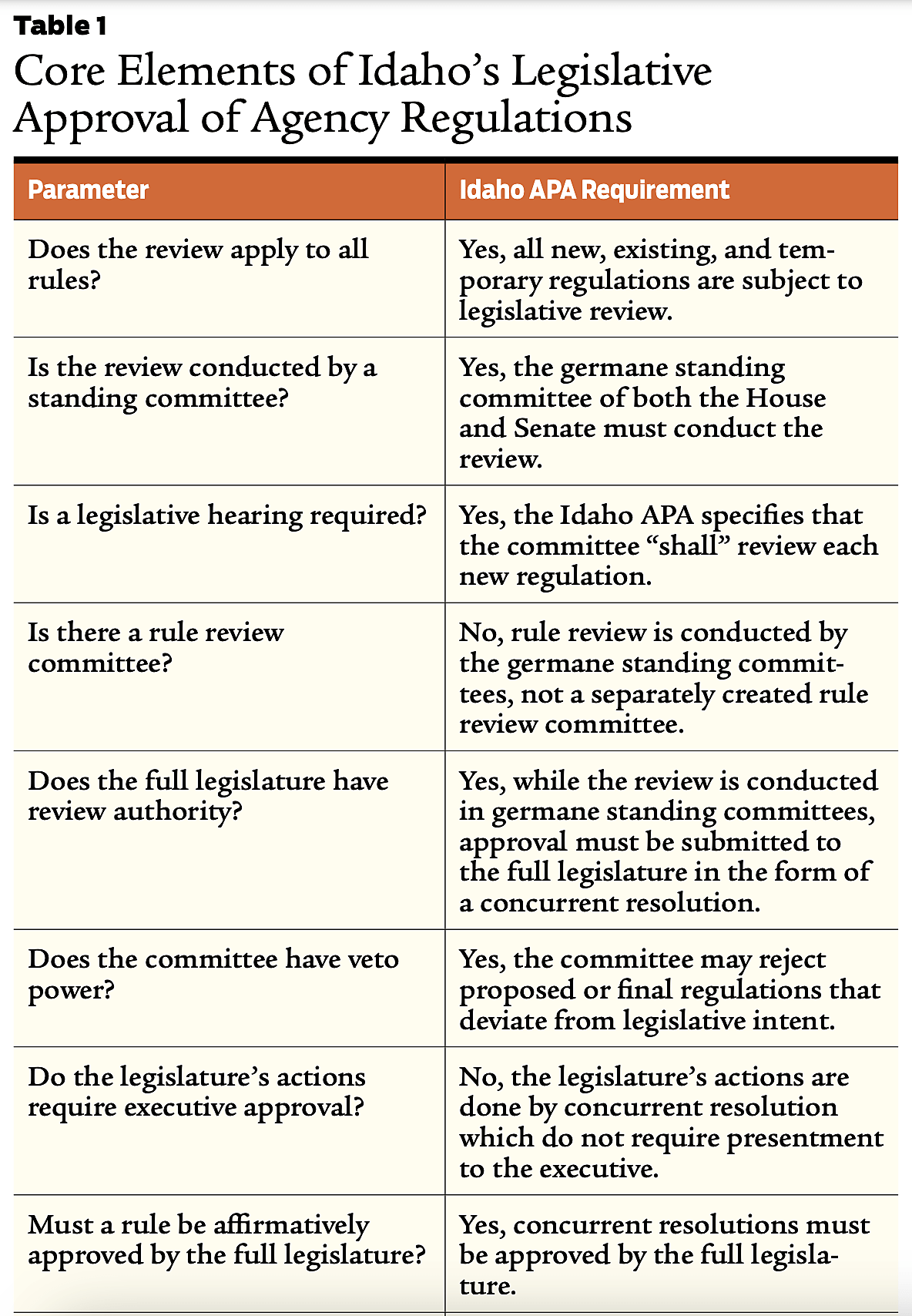

As the REINS Act is primarily focused on congressional approval of major new agency regulations, this article focuses primarily on that aspect of Idaho’s legislative review. Table 1 summarizes Idaho’s legislative approval process according to the criteria set forth by Broughel et al.

In some limited instances, an agency may adopt temporary rules that take effect prior to legislative review. The Idaho APA spells out just three instances in which temporary rules are allowed, specifically if the governor finds the rule will:

- protect public health, safety, or welfare,

- ensure compliance with deadlines in governing law or federal programs, or

- confer a benefit. (This provision was changed in the 2024 legislative session to “reduc[e] a regulatory burden that would otherwise impact individuals or businesses.”)

In each case, the regulation must still be approved by the legislature for it to be extended for another year as a temporary rule or for it to be made permanent.

It is with this backdrop that this article uses Idaho as a comparator for potential effects of a federal REINS Act. It leverages data from the Office of Administrative Rules Coordinator (OARC) and Idaho State Legislature for the 2010–2019 legislative sessions, specifically the History Notes Index published at the end of each legislative session by OARC, and the Progress Reports published at the end of each legislative session. To calculate the rejection rate for regulations, this article uses rule dockets as the unit of measurement. Rule dockets are analogous to bills presented by the legislature. Rule dockets may contain single or multiple changes to rules, though they must have a single subject that ties them together. Further rule dockets may contain brand new regulations or incremental amendments to existing regulations.

Rejection

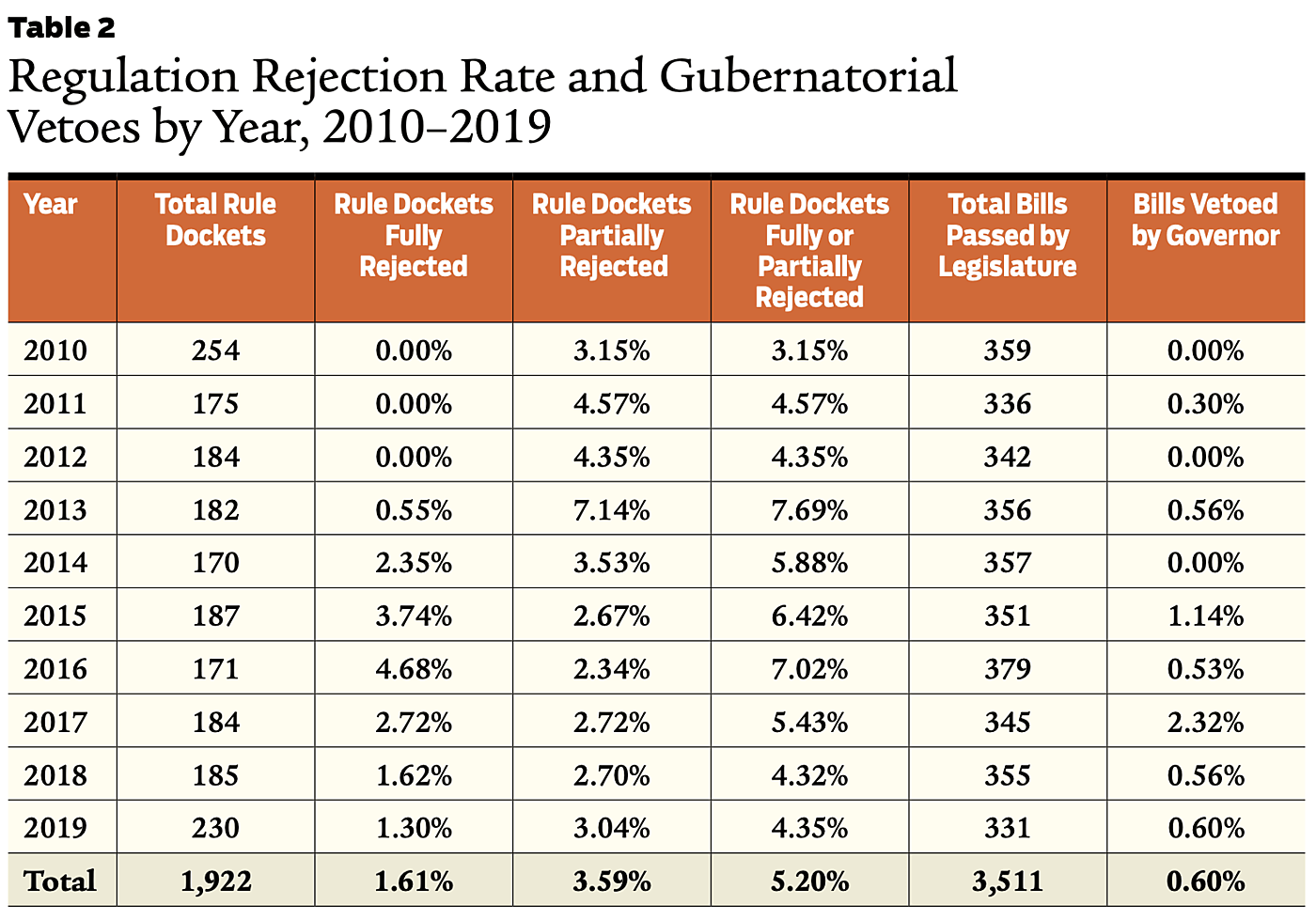

Table 2 summarizes the legislature’s regulation rejection rate for each year from 2010 through 2019. Idaho agencies brought an average of 192 rule dockets annually, and the legislature fully rejected 1.6 percent of rule dockets and partially rejected 3.6 percent, for a total rejection rate of 5.2 percent. For comparison, the legislature passed an average of 351 bills annually, of which the governor vetoed 0.6 percent during the same period.

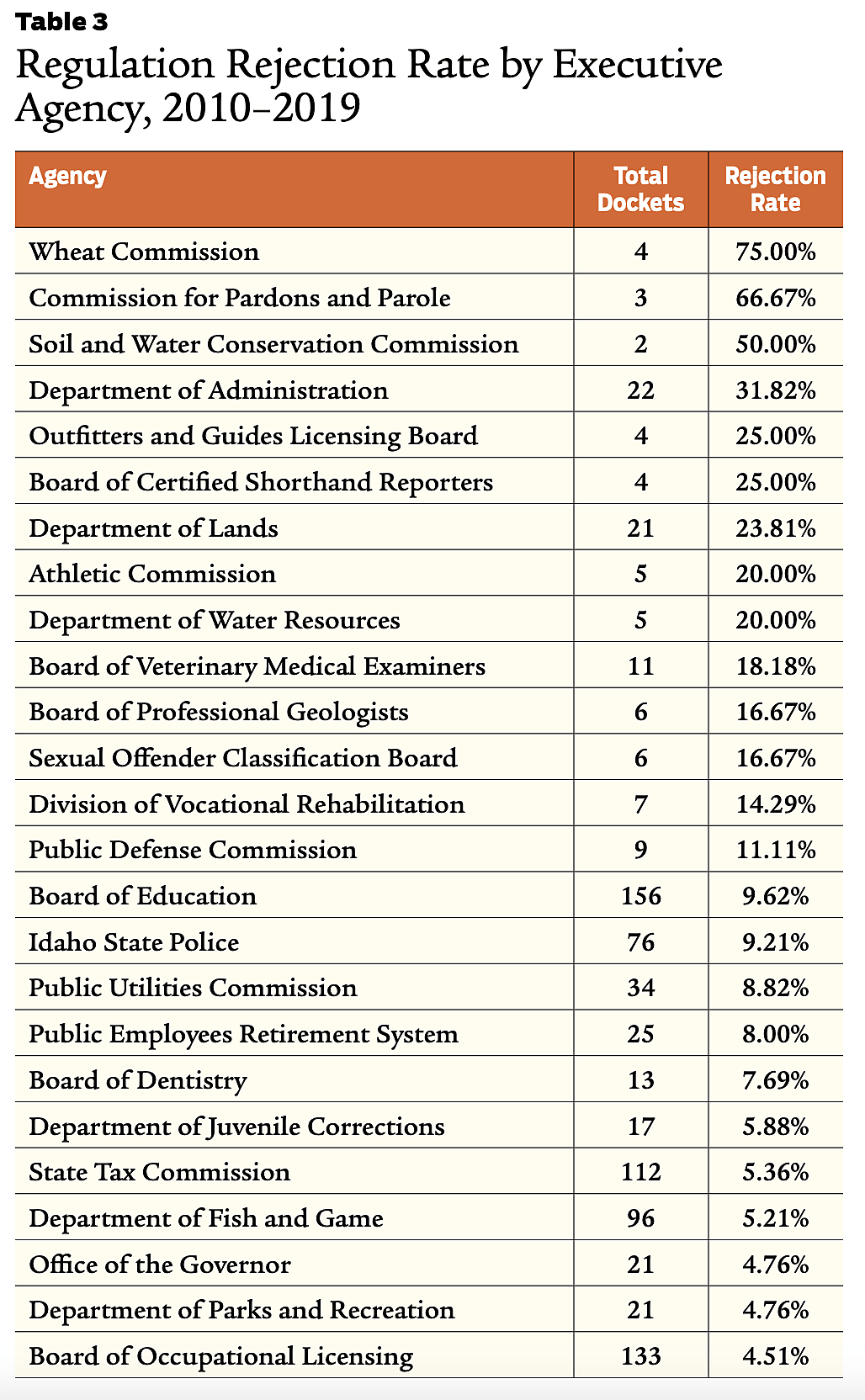

Rejection by agency / Table 3 summarizes the regulation rejection rate for the 25 state agencies with the highest cumulative rejection rates from 2010 through 2019. A total of 61 state agencies promulgated regulations during this timeframe, with an average of 31.5 dockets per agency (range of 1–313 dockets). The statewide rejection rate was 5.2 percent for all agencies, with an agency-specific range of 0–75 percent depending on the agency. The three agencies with the highest rejection rates promulgated relatively few regulations during the period, so their rates were influenced in part by small denominators.

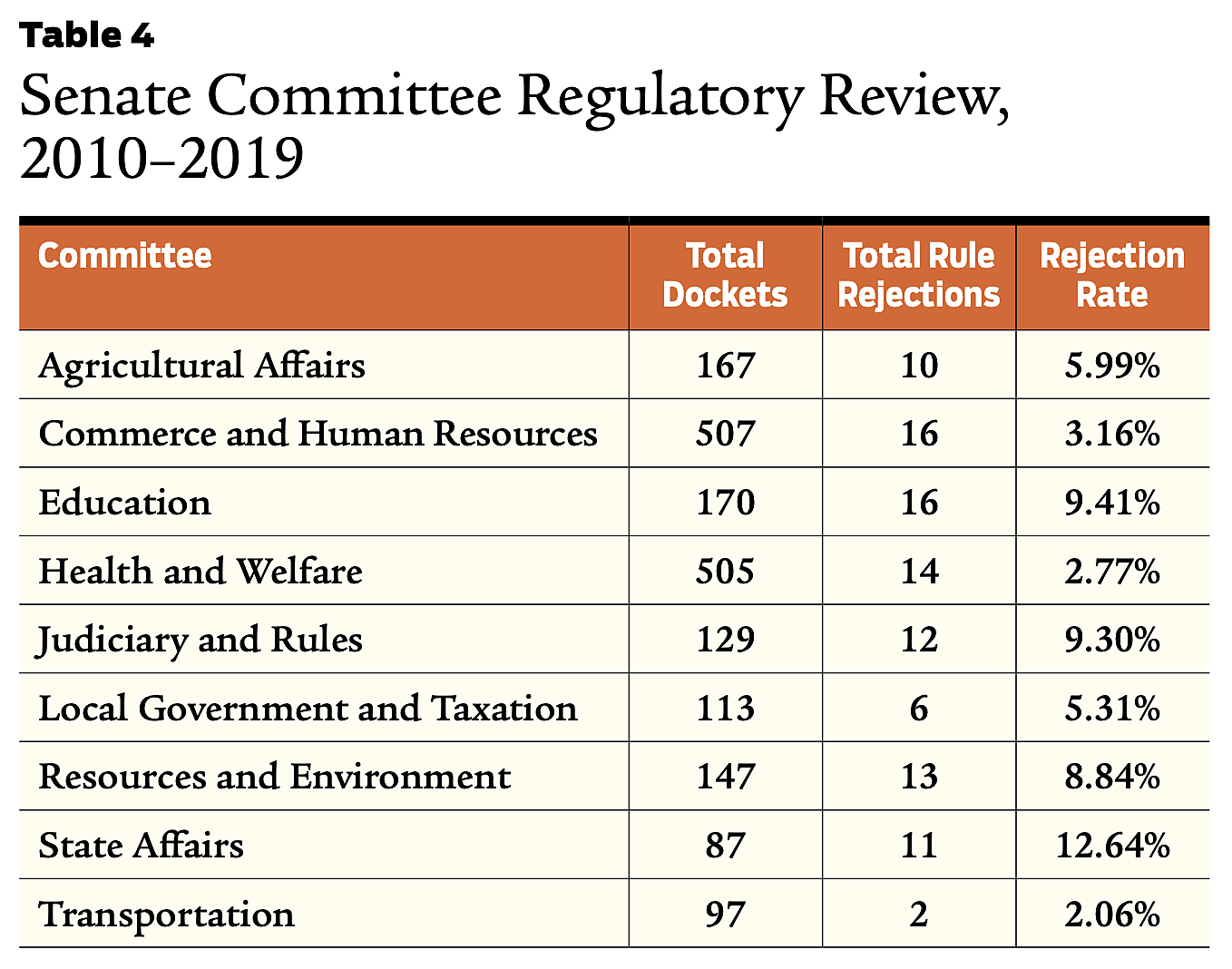

Rejection by legislative committee / Table 4 summarizes the regulation rejection rate for each of the Senate standing committees that are assigned regulations for review. Each committee rejected rules during the study period, but the rate ranged from 2.06 percent for the Transportation Committee to 12.64 percent for the State Affairs Committee.

Effects

Three years of Senate standing committee agendas were reviewed, spanning 2017–2019. Senate committees held 661 meetings during this three-year stretch, of which 24 percent included review of at least one rule docket as part of the agenda (range of 12–37 percent). Regulatory workload was highest in the Commerce and Human Resources committee (37 percent of meetings), which reviews regulations from most occupational licensing boards. On average, committees completed their final rule docket review 32 calendar days after the start of legislative session (range of 26–39 calendar days).

Temporary regulations were used sparingly during the study period, with just 69 total dockets issued by 19 agencies. Thus, temporary regulations accounted for just 3.5 percent of total regulations put forth by the executive branch. Temporary regulations were highly concentrated with the Department of Health and Welfare, which accounted for 45 percent of temporary regulations.

For the study period, total regulations grew by 871 pages, with an average annual growth of 96.7 pages (range of 41–176 pages) statewide. For 2016–2018, the legislature rejected 7 pages of regulations, which is equivalent to 2.1 percent of the pages of regulations added during that time. Assuming this same rate over the entire study period, regulations would have been 18 pages longer were it not for the legislative review.

Discussion

Idaho’s part-time legislature was able to conduct regulatory review focusing on legislative intent and integrate regulatory approval into a 75-to-90-day legislative session. Standing germane committees typically completed review of regulations 32 calendar days following the start of a legislative session, even with an average volume of rule dockets that is on par with 55 percent of the average annual volume of bills passed by the legislature.

To make this work, executive branch agencies must complete their regulatory work in a timeframe that is relevant to submitting to the legislature for review. Legislative review in a state with a year-round legislature or to the federal government likely would have more flexibility and would occupy a smaller percentage of standing committee agendas, though this would ultimately be determined by:

- the volume of regulatory activity that triggers legislative review,

- the nature of the regulations involved, and

- the scope of the legislative review (e.g., ensuring conformity to legislative intent versus reviewing the underlying policy decisions).

Even with a Republican-led executive branch and supermajority Republican legislature, not all regulations were approved by the legislature. Partial rule rejections were more common than full rule rejections, with an overall rejection rate of 5.2 percent. Put another way, the legislature approved 94.8 percent of all regulations, with an approval rate ranging from 92.3 percent to 96.9 percent depending on the year. Some may see this high approval rate as a sign of superficial oversight but, again, the regulation rejection rate exceeded the rate of executive vetoes of bills passed by the legislature. Thus, even in a state with a unified government based on the predominant party of both legislative chambers and the executive branch, some proposed regulations were still rejected.

One potential explanation for the higher regulation rejection rate as compared to the bill veto rate may be the natural filtering of bills that occurs through the legislative process. Through committee hearings and floor debate, it is not uncommon to find unanticipated problems with well-intentioned bills, stakeholder opposition, or differing opinions among legislators, resulting in some bills failing to progress. For example, in the 2018 Idaho legislative session, 799 pieces of new legislature were prepared, of which 561 bills (70 percent) were introduced and 355 bills (44 percent) passed both chambers. Thus, while the governor vetoed just two bills that year, more than 444 bills (56 percent) stalled and therefore were not presented to the governor. It is possible that if many of those failed bills did reach the governor’s desk, a larger proportion of bills would have been vetoed.

It is likely, however, that some filtering occurs with regulations, though we are not able to quantify the rate based on available data as it does not always play out in the public arena. Agencies may not initiate rulemaking because of stakeholder feedback or agencies may decide to shy away from topics that are unlikely to elicit legislative approval. Thus, legislative review of regulations may have an unquantifiable effect on deterring regulations by executive branch agencies. Some have suggested that the “mere possibility” of legislative review may have “a powerful controlling effect” on an agency’s regulatory behavior.

Legislative review of regulations had only a modest effect on overall regulatory volume. Regulations grew by an average of 97 pages a year, though this would have been two pages higher without the legislative rejections of regulations. Thus, regulations still grew on net, and in no studied year was there a net year-over-year reduction in regulatory volume.

It has been postulated that one unintended consequence of this deterrent effect is that agencies will simply pivot from regulations to other forms of soft law like guidance documents. This can be mitigated by the state making clear, as Idaho’s APA does, that policy statements and guidance documents do not have the force and effect of law. In the same manner, some may contend that legislative review incentivizes executive agencies to default to temporary rulemaking to circumvent legislative approval. This has not proven to be the case. Temporary rulemaking accounted for just a fraction of regulations (3.5 percent). Temporary rules by their very definition last for a short period of time and still require the legislature to extend them or make them permanent.

One final concern expressed about legislative review of regulations is that it would be a recipe for inaction. This was not the case in Idaho, where executive agencies still averaged 192 rule dockets annually. While it is difficult to say how many dockets agencies would average in the absence of legislative review, Idaho was rated as the fourth least regulated state based on volume during the study period. While previous studies of the effects of legislative review of regulations have been mixed, it is reasonable to deduce that legislative review partly accounted for the relatively low volume of regulations in Idaho. To the extent legislative review is a driver, it is likely due to unobserved deterrent effects as opposed to actual rejection of regulations, given the observed high approval rate and net growth in volume during the period.

Conclusion

While the REINS Act continues to be given consideration at the federal level, insight into its practical implications can be gleaned from states that already require legislative review of regulations. Idaho has long required legislative review and has an approval rate ranging from 92.3 percent to 96.9 percent depending on the year. Executive agencies have adjusted rulemaking procedures to allow for legislative review of regulations, and legislative committees typically complete their reviews in 32 calendar days. Legislative review of regulations may have a deterrent effect that may prevent the advent of regulations that are unlikely to elicit legislative approval.

Readings

- Adler, Jonathan H., 2011, “Would the REINS Act Rein in Federal Regulation?” Regulation 34(2): 22–28, Summer.

- Broughel, James, Brian Baugus, and Feler Bose, 2022, “A 50-State Review of Regulatory Procedures,” working paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

- Doyle, Richard B., 1986, “Partisanship and Oversight of Agency Rules in Idaho,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 11(1): 109–118.

- Simon, Herbert, 1997, Administrative Behavior, 4th ed., Macmillan.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.