Much has changed since then, including the migration of many consumers from traditional cable and satellite service to streaming. One thing that has not changed, and that I discussed at length in my article, is the use of “most favored nations” (MFN) clauses and their effects on beloved independent programming providers like Hallmark Channel and Reelz. Regulators are now maneuvering to remedy this.

In markets, an MFN clause in a contract between two parties gives one party the legal right to terms and benefits equal to those received by anyone else who enters into a similar contract with the other party. So, for instance, if a provider is offering a good to one purchaser at a discounted rate, that provider must offer the same rate to other purchasers that have an MFN clause in their contracts. In the pay TV market, an MFN clause is a promise from a programming provider that every distributor can receive the same deal—or the same specific provision—offered to any other distributor.

MFNs limit the ability of independent programmers to take advantage of the opportunity that cord-cutting affords them to reach audiences without a distributor intermediary, while concomitantly constraining the independents’ growth in the traditional cable/satellite sector. As a result, MFNs effectively reduce the amount (and diversity) of programming consumers have access to. A recent Notice of Proposed Rulemaking by the Federal Communications Commission would largely do away with MFN use in this market. Such a development would benefit those media consumers who still get most of their content from cable or satellite systems.

The industry / The number of available video offerings has grown exponentially over the last four decades. That growth has accelerated of late with the rapid expansion of video streaming over the internet—and outside of the traditional cable and satellite distributors. Today there are hundreds of video programming networks, and billions of dollars are spent each year producing and acquiring the rights to shows, movies, sporting events, and myriad other types of content for distribution.

There are four major distributors (or “Multichannel Video Programming Distributors”) in the United States through which a majority of households get their video programming: Comcast, Charter, AT&T/DirecTV, and DISH. Despite the dramatic trend toward internet streaming of programming, 56 million households still access video programming networks via a cable or satellite distributor subscription, representing 43 percent of all US households.

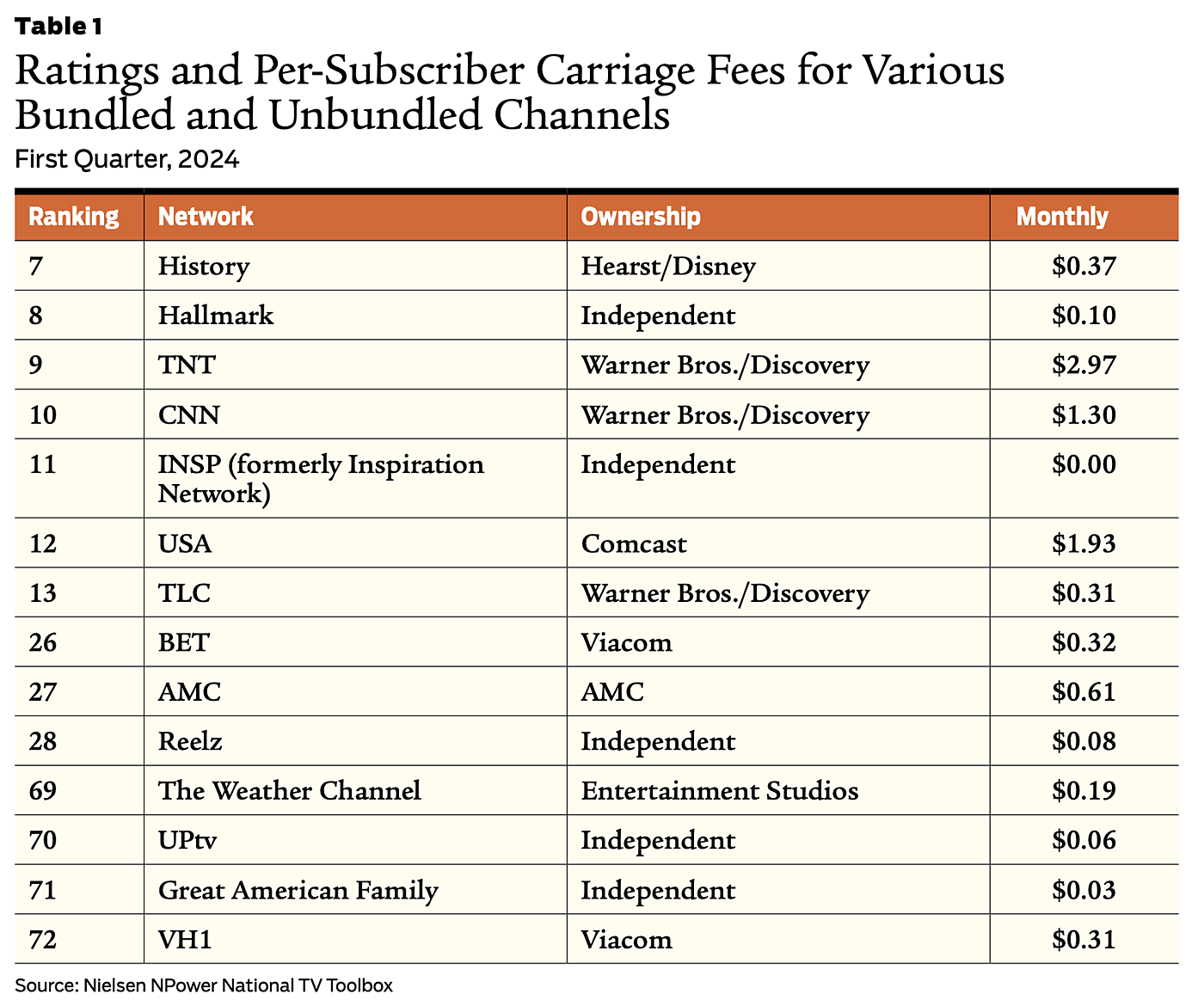

Two major factors drive distributor costs: the capital investment and service costs for deploying and maintaining their systems and the cost of acquiring content. Distributors negotiate carriage rights with the programming networks and typically pay a monthly per-subscriber “carriage fee” for each channel. Programming networks make their money both from the fees as well as the advertising they sell on their channels.

Most programming channels are members of network families, many of which are owned by major distributors. For instance, Comcast owns NBC, CNBC, Bravo, E!, and a few other networks. Large multimedia companies also own suites of networks: Disney owns ABC, Lifetime, A&E, the Disney Channel, and ESPN and its sister networks. Fox, Viacom, Time Warner/Discovery, A&E, and AMC are other multimedia companies that have multiple networks. These entities negotiate the carriage fees for their entire lineup of channels as a package.

The small number of cable and satellite distributors can leverage their collective oligopsonistic market power to pay lower prices than if there were real per-channel competition. An effective oligopsony would result in fewer program networks and fewer programs. The distributors wouldn’t necessarily pass those lower costs onto consumers because there are no market forces nudging them to do so.

However, the oligopsonistic distributors mainly negotiate with an oligopolistic group of multimedia companies that own most of the networks: 97 of the 108 most-watched channels are owned by one of the major multimedia companies. Oligopolies—much like monopolies—extract higher prices from buyers and concomitantly sell less than the efficient amount.

Table 1 compares the fees paid by distributors to selected independent channels as well as to comparably rated channels owned by oligopolies. The table shows that ratings and household delivery do not directly translate into the value of subscriber fees that distributors grant to independent networks. The independent networks receive a fraction of the monthly subscriber fees paid to networks with similar or lower Nielsen ratings owned by large multimedia companies. The bargaining power of the large programming conglomerates allows them to extract higher fees for their channels.