Certificate-of-Need (CON) laws restrict entry and/or expansion of healthcare facilities in 35 states. These laws require hospitals, nursing homes, ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs), and other healthcare providers to obtain regulatory approval before opening a new practice, expanding, or making certain capital investments. Thus, CON laws effectively create barriers to entry that limit competition among medical providers.

The evidence is overwhelming that individuals in states with CON laws have reduced access to medical care and the medical care in those states is higher-cost and lower-quality than in states without CON laws. However, the majority of this research shows correlations but does not show that CON laws cause reduced access, higher expenditures, and lower quality.

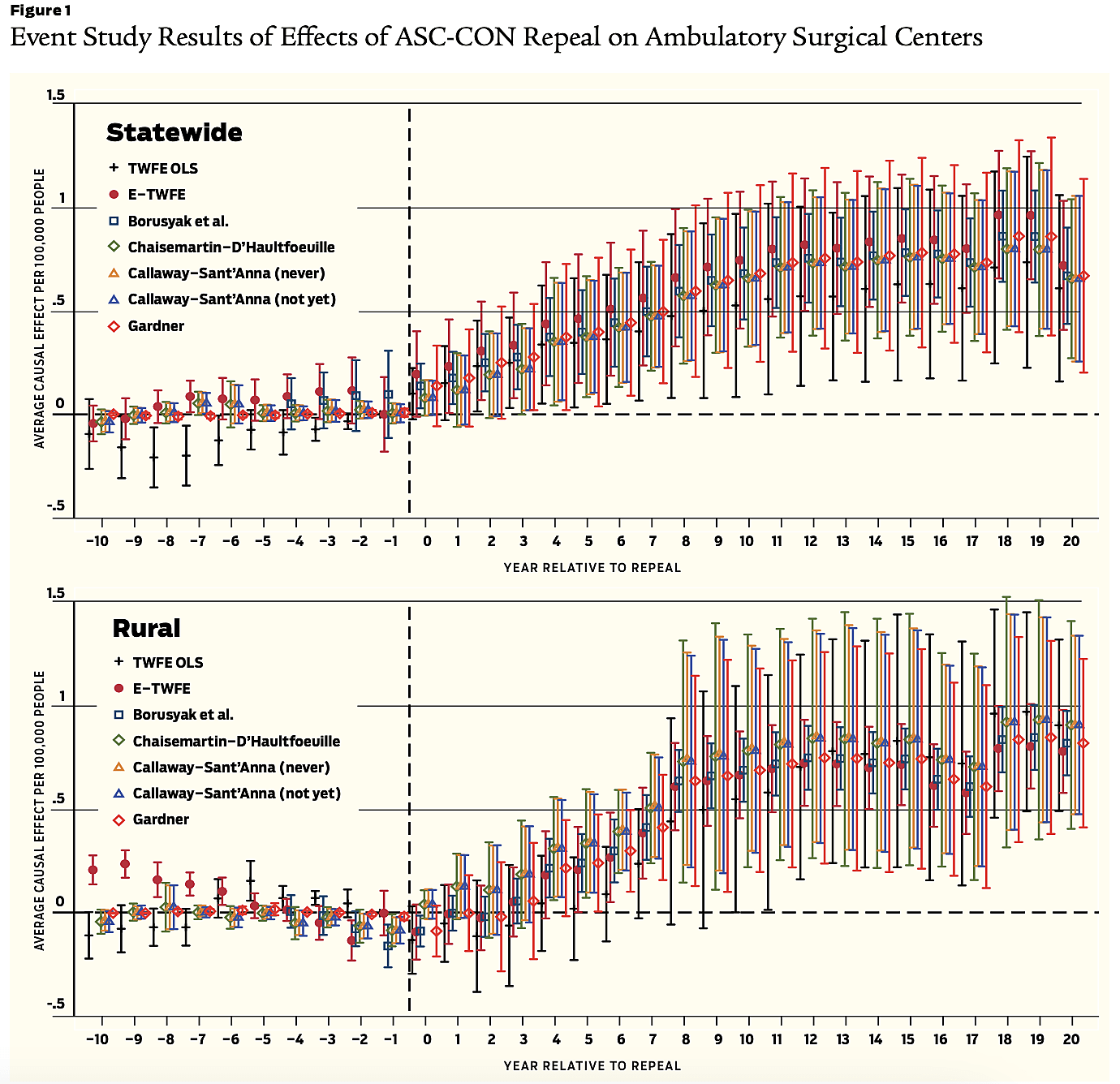

We test whether this relationship is causal. Between 1991 and 2019, six states repealed their CON laws on ASCs. We take advantage of this and employ a difference-in-difference design using several unbiased estimators to determine whether CON laws are the cause of reduced accessibility of healthcare services. Our findings show this is the case. Repealing ASC CON laws cause a statewide increase in ASCs per capita of 44–47 percent and, contrary to the goal of preserving healthcare access in rural and underserved regions, we find that repeal increases ASCs per capita 92–112 percent in rural communities.

Our findings also shed light on why CON laws have failed to achieve the goal of reducing healthcare spending. Because of cost differences, Medicare typically reimburses providers substantially more for a surgery performed in an in-patient or hospital, relative to out-patient, setting. For instance, Medicare reimburses around $2,900 for a knee arthroscopy performed in a hospital outpatient department compared to only $1,650 for the same procedure in an ASC. By limiting the number of available ASCs, CON laws not only reduce competition between ASCs but also direct surgeries, many of which are inelastically demanded, to the substantially more expensive hospital setting, increasing healthcare expenditures and burdening taxpayers.

Background / In 1980, most surgeries took place in hospitals as in-patient procedures, with only 16 percent performed on an outpatient basis in a few hundred ASCs nationwide. Facilitated by technological innovations in anesthesiology and less invasive surgical techniques, the market for surgeries looks dramatically different today. Some 80 percent of surgeries take place in outpatient settings across almost 6,000 surgical centers nationwide. CON laws are impeding this shift in 28 states, preventing patients’ ability to access convenient high-quality surgeries.

A rationale for restricting ASCs’ entry is to prevent them from taking the most profitable patients away from rural hospitals, what is sometimes called “cream-skimming.” CON advocates claim that limiting ASC entry reduces cream-skimming, assuring hospitals’ viability and access to essential services that require cross subsidy. These arguments that CON ensures healthcare access in rural areas has remained a central justification of state CON legislation.

We test the implications of the cream-skimming hypothesis. Does repeal of ASC CON laws increase hospital closures or reduce medical services? Our findings do not support the arguments of CON advocates who claim the laws reduce cream-skimming by ASCs and prevent hospital closures. The repeal of CON laws does not appear to have negative effects on access to hospital services. Rather, we find suggestive evidence that repeal facilitates access to rural hospital services by reducing the size and potentially the frequency of hospital service reductions.

Brief history / Policymakers enacted CON laws to control healthcare costs, regulate the level of capital investments, increase charity care, protect the quality of medical services, and protect rural access to medical care.

In 1964, New York became the first state to pass a CON law. Between 1964 and 1974, 26 other states adopted CON legislation. In 1974 the federal government made the availability of some federal funds contingent on the enactment of state CON legislation with the passage of the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act of 1974 (NHPRDA). By 1982, every state except Louisiana had passed a CON law regulating hospitals, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, and ASCs.

As evidence accumulated that CON laws were failing to achieve their goals, several states, including Texas, Arizona, and Utah, repealed them. In 1986, Congress repealed the NHPRDA, ending the federal government’s subsidization of state CON laws. After that, more states repealed their CON laws. By the end of the 1980s, 12 states had eliminated at least some of their CON laws (Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Minnesota, New Mexico, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Wisconsin, and Wyoming). Between 1990 and 2000, three states followed (Indiana, North Dakota, and Pennsylvania). Since 2000, Wisconsin, New Hampshire, Florida, South Carolina, and Montana have eliminated all or most of their CON laws.

After federal repeal, many states adopted rural access to medical services as a primary rationale for maintaining their CON laws. For example, before they were repealed, Pennsylvania’s CON laws required the “identification of the clinically related health services necessary to serve the health needs of the population of this Commonwealth, including those medically underserved areas in rural and inner-city locations.” The North Carolina CON statute states that “access to healthcare services and healthcare facilities is critical to the welfare of rural North Carolinians, and to the continued viability of rural communities, and that the needs of rural North Carolinians should be considered in the certificate of need review process.” A stated goal of Virginia’s CON law is to support the “geographical distribution of medical facilities and to promote the availability and accessibility of proven technologies.” And one of the justifications for West Virginia’s CON laws is that they provide “some protection for small rural hospitals … by ensuring the availability and accessibility of services and to some extent the financial viability of the facility.”

Those states that retain CON laws claim that when more profitable patients use ASCs, hospitals’ ability to cross-subsidize charity care and provide other essential services is reduced. Thus, those policymakers argue, entry restrictions preserve rural access to medical services.

Hypotheses / While CON laws can influence healthcare markets along several margins, we ask whether ASC-specific CON laws act as barriers to entry, given that these laws aim to reduce the number of ASCs in a state. If CON laws are barriers to entry, we predict their repeal will lead to increased ASCs per capita operating in the state. Given the explicit rationale for CON laws to provide access to medical care in rural areas, we add the hypothesis that repealing ASC CONs results in more ASCs in rural areas.

Additionally, CON advocates claim that limits to ASC entry reduce cream-skimming, which protects the viability of incumbent hospitals in rural areas and prevents them from closing. Similar reasoning predicts that this prevents rural hospitals from reducing the services they offer. Examples include hospitals that close their inpatient units but continue to operate at a reduced capacity, converting to standalone emergency departments, outpatient care centers, or specialized medical facilities.

Thus, we test these hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: Repealing ASC CON laws increases ASCs per capita statewide.

- Hypothesis 2: Repealing ASC CON laws increases ASCs per capita in rural areas.

- Hypothesis 3: Repealing ASC CON laws increases hospital closures or reduces hospital services in rural areas.

Data and empirical strategy / We test Hypotheses 1 and 2 using a difference-in-difference design, where the treatment group comprises six states that repealed ASC CON laws between 1991 and 2019: Pennsylvania (1996), Ohio (1997), Nebraska (1999), New Jersey (2000), Missouri (2002), and New Hampshire (2016). States that kept their CON laws throughout our sample period comprise the control group. We estimate the effect of repeal on two annual state-level measures: the number of operating ASCs per 100,000 state population and the number of operating ASCs per 100,000 rural population from 1991 to 2019.

We test Hypothesis 3 by comparing the repeal states to states with CON laws on four measures of reductions in healthcare access over the years 2005–2019: rural hospital closures, service reductions, beds closed, and beds closed in service reductions, all measured per 100,000 rural population. We control for variables such as the rural population as a percentage of the state in 2005, the average unemployment rate from 2005 to 2019, and the percentage change in the rural, Black, Hispanic, and elderly populations between 2005 and 2019. To control for changes to residents’ health status, we include the percentage change in mortality rates from lung cancer or diabetes among residents age 18 and older between 2005 and 2016.

Findings / Repealing ASC-specific CON laws increased ASCs per capita by 44–47 percent statewide, depending on the specific estimators used. In rural areas, ASC CON repeal caused ASCs per capita to increase 92–112 percent, again depending on the specific estimators. The effect of CON laws for ASCs is to reduce patient access to a more accessible, lower-cost, high-quality alternative to hospital-based surgeries. See Figures 1 and 2.

According to the cream-skimming hypothesis, unrestricted entry for hospital substitutes such as ASCs allows entrants to selectively provide services to the most profitable patients, thereby threatening hospitals’ financial prospects. While our models cannot test this claim directly, they test the implications stemming from the cream-skimming hypothesis. Specifically, does CON repeal increase hospital closures and reduce services in rural areas? The point estimates on CON repeal do not support the prediction that ASC entry results in hospital closures or hospital service reductions. Rather, we find suggestive evidence that repealing ASC CONs improves access to hospital services (Stratmann et al. 2024).

One explanation for this suggestive evidence is that ASCs and hospitals serve complementary roles in healthcare markets. ASC entry allows hospitals to focus on surgeries and medical services that are not feasible in ASC settings. This differentiation could lead hospitals to specialize in more complex—and potentially more profitable—surgeries and make the hospital attractive for medical providers specializing in these services.

Another explanation for our findings is that unrestricted ASC entry mitigates one reason hospitals close, i.e., lack of qualified staff. Surgeon departure is the only physician specialty that predicts rural hospital closures, suggesting they are incentivized to continue working when they can also form an ASC.

Readings

- Melo, Vitor, Liam Sigaud, Elijah Neilson, and Markus Bjoerkheim, forthcoming, “Rural Healthcare Access and Supply Constraints: A Causal Analysis,” Southern Economic Journal.

- Mitchell, Matt, forthcoming, “Certificate-of-Need Laws in Healthcare: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature,” Southern Economic Journal.

- Stratmann, Thomas, and Matt Baker, 2021, “Barriers to Entry in the Healthcare Markets: Winners and Losers from Certificate-of-Need Laws,” Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 77.

- Stratmann, Thomas, Matthew C. Baker, and Elise Amez-Droz, 2020, “Public Health in Rural States: The Case Against Certificate-of-Need Laws,” Policy Brief, Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

- Stratmann, Thomas, Markus Bjoerkheim, and Christopher Koopman, 2024, “The Causal Effect of Repealing Certificate-of-Need Laws for Ambulatory Surgical Centers: Does Access to Medical Services Increase?” GMU Working Paper in Economics No. 24–23, June 1.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.