In a July 20th editorial, the Wall Street Journal offered this pithy appraisal of one of the Trump administration’s top economic advisers on the negative consequences of the burgeoning U.S. trade war with the rest of the world: “Peter Navarro says the harm is a ’rounding error.’ He’s out of touch.”

Navarro is an economist and director of the Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy (OTMP), a White House agency created by President Trump. He is one of the rare economists to occupy a high-level advisory role in the White House. A Harvard University Ph.D., he is a stiff protectionist, which is rare among economists.

In June, the OTMP published a report titled “How China’s Economic Aggression Threatens the Technologies and Intellectual Property of the United States and the World.” It argues against the Chinese government’s rule-breaking mercantilism and industrial policy, which are deemed unfair, exploitative, and even extortionist. (Mercantilism includes both protectionism against imports and the promotion of exports.)

This raises the general question of what a national government’s trade policy should be toward a foreign country whose government pursues a mercantilist industrial strategy. A related issue is that Navarro himself was once a promoter of free markets and free trade (and was a contributor to this magazine in its early years). There is, of course, nothing wrong with changing one’s mind; if new evidence contradicts one’s theories, one should change one’s mind. But is today’s protectionist Navarro right, or the young, free-trade Navarro of a few decades ago?

Protectionist Evolution

In 1984, Navarro published a book titled The Policy Game: How Special Interests and Ideologues Are Stealing America. Reading it, I get the sense of a young Navarro who was a politically moderate and mainstream economist. He argued against the producers’ special interests that politically win out over consumers’ diffuse but more important interests. He blamed protectionist corporations and labor unions. He observed that protectionism “as a job program or form of income redistribution … fails miserably.” Invoking the Smoot–Haley tariff adopted at the beginning of the Great Depression, he pointed out the danger of retaliation and trade wars: “And as history has painfully taught, once protectionist wars begin, the likely result is a deadly and well-nigh unstoppable downward spiral by the entire world economy.” Elsewhere in the book he noted, “The biggest losers in the protectionist game are consumers.” He also warned against the danger of using national security as a justification for protectionism.

Fast-forward 23 years to Navarro’s 2007 book, The Coming China Wars: Where They Will Be Fought and How They Can Be Won. Largely devoid of economic analysis, it looks like a pre-write of the June OTMP report. In the book, he argues that China is a totalitarian and corrupt country on the verge of popular revolt, and that the Chinese government is trying to build an empire. Chinese producers, he charges, are guilty of unfair competition: they steal intellectual property, pay low wages, destroy the environment, and are subsidized and supported by their mercantilist government.

His fixation on the U.S. trade deficit and manufacturing industry dates from that book. He advocates environmental and labor standards for China. He speaks highly of trade unions, without which “exploitation cannot be far behind.” He lauds China’s 2006 Five-Year Plan, which was supposed to end that country’s “Adam Smith on steroids” attempt at market liberalization and replace it with government-managed “sustainable growth.”

He still wants to work within the system when he recommends using international organizations and negotiations to pressure the Chinese government to reduce its protectionism. However, he does not exclude “military might to back up the prescriptions.” He also advises the American government to stop running budget deficits that allow the Chinese government to buy Treasury securities and thereby fuel the U.S. trade deficit through upward pressure on the U.S. dollar.

He further developed and espoused his protectionist views in subsequent writings. Navarro contributed a chapter entitled “Benchmarking the Advantages Foreign Nations Provide Their Manufacturers” to the 2009 book Manufacturing a Better Future for America. The book was published by the Alliance for American Manufacturing (AAM), which describes itself as “a select group of America’s leading manufacturers and the United Steelworkers.” Navarro’s chapter provides a rare glimpse into his current theoretical framework. He argues that the conception of free trade pioneered by David Hume, Adam Smith, and David Ricardo—which lies at the foundation of the modern economic analysis of trade—is inapplicable to today’s conditions for two reasons: First it is not true that “all free trading countries … refrain from the practices of either mercantilism or protectionism.” Second, not all trading countries have automatic adjustment mechanisms that prevent chronic trade imbalances. In other words, the world is protectionist and therefore America must be, too. Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage—a cornerstone of modern economic understanding of trade—is briefly mentioned and summarily dismissed.

Navarro’s 2011 book Death by China, coauthored with Greg Autry, an assistant professor of “clinical entrepreneurship” at the University of Southern California, argues that the United States and China are in an “undeclared state of war” and that a real, non-trade war between them is possible. Consequently, American industrial capacity must be protected against Chinese competition. Navarro and Autry point out that countries in the “free world,” such as Japan, Mexico, and Germany, are “our real free trade partners.” Yet the book generally views trade and trade negotiations as analogous to war. Trade unions must protect jobs against shoddy and dangerous Chinese products. A companion documentary film, produced by Autry and partly financed by steelmaker Nucor, is even more radically protectionist.

In 2015, Navarro published Crouching Tiger: What China’s Militarism Means for the World. It deals mainly with a future military confrontation between the United States and China, and ways to prevent it if possible. It too has a companion documentary, subtitled “Will There Be a War with China?” In both, Navarro argues that the U.S. government must build a strong military advantage over China with the help of its allies. American consumers must stop financing China’s own military expansion with their purchases of Chinese goods. A “trade rebalancing” would “slow China’s economy and thereby its rapid military buildup,” according to the book. “It would also provide America and its allies with both the strong growth and manufacturing base these countries need to build their own comprehensive national power.”

Last June, the news and commentary website Axios prodded Navarro on why he had changed his opinions on trade so radically after The Policy Game. He explained that after China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, he realized that free trade cannot work when it is not fair—for example, when one of the countries involved practices “non–market economy industrial policies.” “The traditional approach to evaluating tariffs,” he wrote for Axios, “ignores the external costs or ‘negative externalities’ associated with unfair trade.” These “externalities” include the loss of factories, jobs, and incomes, and their consequences in workers’ lives.

In his writings, Navarro makes five distinct arguments against open trade with China and other countries. They can be summarized as follows:

- The impossible-competition argument: We cannot compete against a dirigiste and even totalitarian country like China. Trying to do so generates negative externalities.

- The fairness argument: “Unfair” trade is not free trade and is destroying the American economy.

- The trade deficit argument: The U.S. trade deficit is a serious problem that reduces gross domestic product and indicates unfair trade.

- The retaliation argument: Retaliatory protectionist measures are justified against protectionist countries; such retaliators are the real free-traders.

- The national security argument: Protectionism is required for reasons of national security.

Many of these arguments are now echoed by large groups of the America public. I examine each of them in the following sections.

The Impossible-Competition Argument

Navarro and others invoke China as an extreme case that authoritarian governments make for bad trading partners. Of course, he is right to describe the Chinese state as authoritarian and repressive, if not totalitarian.

In 2012, Nobel economics laureate Ronald Coase and co-author Ning Wang of Arizona State University published a book titled How China Became Capitalist, describing the country’s economic evolution after the accession of liberalizer Deng Xiaoping in 1978. (See “Getting Rich Is Glorious,” Winter 2012–2013, and “The Power of Exchange: Ronald H. Coase 1910–2013,” Winter 2013–2014.) However, conventional wisdom holds that those reforms have been reversed in recent years.

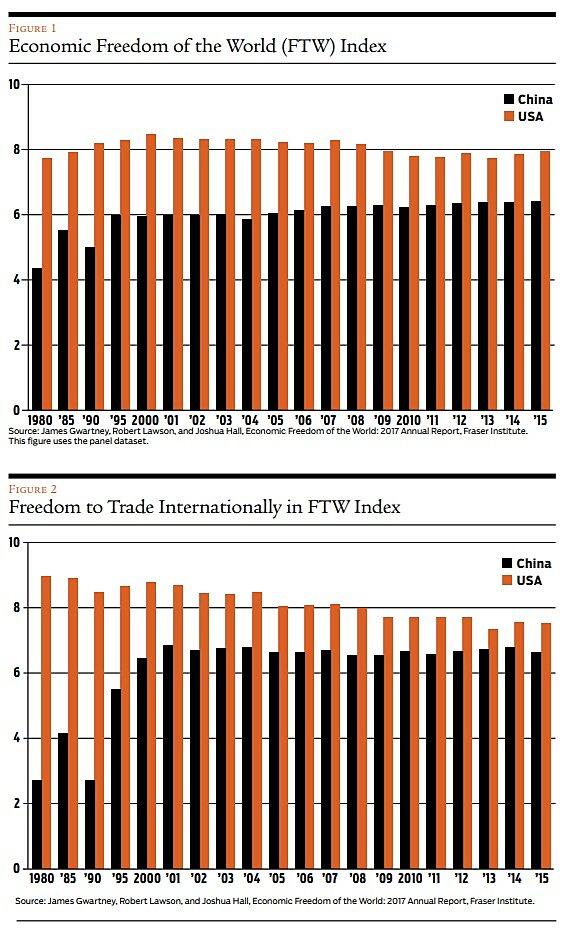

Economic freedom in China / But things are not as simple as the conventional wisdom—and Navarro—suggest. Consider China’s scores on the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World index (FTW). The index combines indicators of the size of government, commitment to the rule of law and property rights, soundness of the national currency, freedom to trade internationally, and scope of regulation. An index like this must be used with caution, but China’s scores over time suggest the country continues to make progress—albeit sometimes haltingly—toward economic freedom.

Figure 1 compares China’s overall FTW score to the United States’ in recent years. Perfect freedom would get a score of 10. Economic freedom in China increased markedly from 1980 (the first year available) through the years preceding the country’s accession to the WTO in 2001, with the exception of a dip around the time of the Tiananmen Square events and Deng’s retirement in 1989. Economic freedom in China has continued to rise since 2001, although more slowly.

In the United States, on the contrary, economic freedom as measured by the FTW has generally decreased since 2000. Obviously, freedom is much more advanced in America, but the comparative trend is interesting. (Another index of economic freedom, compiled by the Heritage Foundation, shows the United States dropping from the “free country” category to “mostly free” in 2010.)

Figure 2 charts the index component “Freedom to trade internationally,” which measures the absence of domestic barriers to trade. The figure suggests this freedom has been declining in the United States while, in China, it dramatically increased until 2001, and has remained more or less constant since. Over the whole period 1980–2015, the change in the freedom to trade more than explains the change in the total economic freedom index for both China and the United States. Given those trends, it is not clear that the Chinese government has become less of a free trader.

In their 2011 book, Navarro and Autry characterized the Chinese economic system as a “brand of state capitalism,” which is not false. But if we want to speak in those terms, it can be argued that the American system is another brand of state capitalism (or crony capitalism), as the current protectionist push illustrates. And Ning Wang remains optimistic for China; in comments to me he indicated his belief that “overall, China is still on its way to capitalism.”

Convenient scapegoat / Many arguments against Chinese imports are exaggerated. In Death by China, Navarro and Autry wrote that “China has stolen millions of American manufacturing jobs” and that “if we had held onto those jobs, America’s unemployment would be well below 5%.” In writing this they confounded macroeconomic factors and trade issues. In May 2016, five years after their book was published, the U.S. unemployment rate was 4.7%, and it has continued declining ever since.

How to explain the low unemployment given the jobs “lost” to China and elsewhere? They were replaced—and then some—by other jobs. During the so-called “China shock” between 1999 and 2011, when U.S. imports from China grew rapidly and job disruptions followed (in certain manufacturing industries), 5.6 million net jobs were created in the U.S. economy.

Jobs are a poor measure of worker welfare, of course; otherwise, destroying machines and computers would be good policy because more workers would then be required. What matters is income. During the same period, real U.S. income (real GDP) increased by 26%. All this occurred despite the worst recession since the Great Depression.

The value of the goods imported from China is also often exaggerated. According to research done at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the proportion of American consumer expenditures that go to China, including the value of the Chinese inputs incorporated into what’s produced in America, is 1.9%. This is because Chinese goods occupy a big share only in relatively small categories of consumer expenditures (such as clothing and shoes, or furniture and household equipment), and because two-thirds of what Americans consume is composed of domestic services—such things as health care, education, and housing.

Irrational fear / But isn’t Chinese industrial policy a great threat? No. It is an error to believe, contra economic theory and history, that the controlled enterprises in a country dominated by a communist government can constitute a grave danger for efficient capitalist enterprises. No private car manufacturer would have feared import competition from Trabants, the shoddy East German cars whose production did not survive the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In the 1970s and 1980s, similar fears were expressed about Japanese industrial policy and the country’s supposedly all-powerful Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI). There was no comparison between Trabants and Japanese cars such as Hondas or Toyotas: Japanese cars were state-of-the-art machines built by private companies. Yet the threat to the U.S. economy posed by the Japanese turned out to be greatly exaggerated.

If China is backsliding from a market economy, then Western producers have little to fear. And if China isn’t backsliding and its producers make advances in freedom and economic efficiency, then that is good for all of mankind. Competition from state-dominated businesses, even if “unfair,” is not a big threat, and fair competition from capitalist firms can only be good, whether that competition is domestic or foreign.

Externality argument / Navarro’s “externality” argument is remarkably shoddy. First, note that outcompeting producers is not technically an “externality,” but the normal result of a free and flexible economy where “creative destruction” occurs. If the result of competition is considered an externality, everything in economic life is an externality and the concept becomes useless.

Economic disruptions can produce, in Navarro’s terms, “socioeconomic costs in the forms of higher crime rates, drug use, and suicide rates.” Perhaps these sorts of costs can be considered externalities for affected communities. They may correspond to what many people view as the problems with free trade. But research has shown that international trade has accounted for at most 20% of the reduction of manufacturing employment in the United States and other developed countries; the rest is due to technological progress, which has reduced the need for labor. Technology is by far the main disruptive factor. A stagnant society without technological change would face different problems and costs, which most people would find far worse than the incidental costs of economic growth.

The costs of economic disruptions that are shouldered by the welfare state (through unemployment insurance, trade adjustment assistance, Medicaid, and such) seem to be another reason why some people object to free trade. But hasn’t the welfare state been created precisely to provide a safety net in a dynamic society? People who object to free trade on that basis should also want to block any social, technological, and economic change.

The Fairness Argument

Perhaps what people resent is competition based on allegedly unfair advantages that create an “unlevel playing field.” This fairness argument may be the foundation of all other protectionist arguments, in the general public and among politicians. It’s an important argument that needs to be addressed.

In a June 21st, 2011 Los Angeles Times op-ed, Navarro argued that the Chinese manufacturing advantage “is actually a complex array of unfair trade practices, all of which are actually illegal under free-trade rules.” He mentions piracy and counterfeiting, the undervalued yuan, the “forced” transfer of technology from American companies engaged in joint ventures in China, and the lack of American-like environmental and labor regulation in China.

Intellectual property theft can be dealt with, at least partly, through the WTO and ordinary courts, even Chinese courts. “American IP owners have in recent years enjoyed increased success in enforcing their rights in Chinese courts,” Stanford law professor Paul Goldstein has observed. New international treaties or rules can be devised to address ongoing concerns.

It is worth noting that, at the time of the American industrial revolution, the U.S. government did not protect foreign intellectual property. Not until 1989 did the U.S. government adhere to the 1886 Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works. Moreover, a good argument can be made that the definition of intellectual property has been extended too far in the past few decades. (See “The Ideal Fox in the Ideal Henhouse,” p. 73.)

The transfers of technology that American companies are often required to accept when they establish joint ventures in China are certainly objectionable, but nobody is obliged to set up shop in that country if the costs imposed are higher than the benefits. At any rate, this requirement violates the WTO rules, as Navarro admits, and eventually could be solved at that level.

If the Chinese yuan was once undervalued, the International Monetary Fund and most economists recognize that it is not so anymore. From mid-2005 to late July 2018, the yuan increased in value 18% against the dollar, even counting the 8% drop since April 2018 when American protectionism started battering the Chinese currency. In its twice-yearly reports, the U.S. Treasury has continuously declined to declare the Chinese government a “currency manipulator.” At any rate, a national state cannot undervalue its currency for very long because doing so requires an increasing money supply, which generates domestic inflation and exerts an opposite effect on the currency. Otherwise, it would be a breeze for any mercantilist state to increase exports and decrease imports by simply inflating the currency, even if doing so would be illegal under WTO rules.

As for the lack of labor and environmental regulations in China, why should that be an issue? There were no such regulations in America and other Western countries when they started growing during the Industrial Revolution. Are rich Western producers (including trade unions) now going to dictate such regulations in developing countries? This sort of fairness looks rather self-serving and unfair.

China is still a relatively poor country, with a GDP per capita equal to 28% of the American level, about what it was in the United States in 1950. China’s remarkably high rate of growth since 1980 (about 5.5% per year) was due to an economic takeoff in a context of liberalization, more or less the same thing that happened in Western countries with the Industrial Revolution. In fact, China grew faster in a shorter amount of time because it had the advantage of being part of an already rich world. But such high growth will not continue for long if liberalization stalls. (And it should be noted that there have been questions over the years about the Chinese government inflating its GDP statistics in order to exaggerate the country’s growth.)

Unfair for whom? / In general, low wages in poor countries are not “unfair.” It is because of their low wages that they have a comparative advantage in some economic sectors. Advanced countries have a comparative advantage in sectors more intensive in capital—including the human capital of specialized workers. This is a conclusion of the theory of comparative advantage that Navarro ignores as he focuses on helping and bailing out some producers, which is a way to undermine prosperity.

If Americans can consume more by producing something in which they have a comparative advantage and exchange it on world markets, they will generally be better off. The drop in the price of clothes, household appliances, and furniture during the past few decades is testimony to the benefits of international trade. Producers will complain of unfairness when they are outcompeted in fields where they don’t have a comparative advantage, but there is no reason to yield to these special interests, as the young Navarro correctly argued.

If the Chinese government is more mercantilist than the U.S. government, for whom is this unfair? Certainly not American consumers, who obtain cheaper goods thanks to the hapless Chinese taxpayers who pay the subsidies. American producers—shareholders and workers in import-competing industries—will, of course, be affected and capital and labor will have to move to other industries, as we have seen in the case of old-style manufacturing. But consumption is the goal of production, not the other way around. And these subsidies help Americans to consume more, at Chinese expense.

Tariffs and other protectionist measures mainly hurt the poor, who devote a larger proportion of their incomes to physical goods. In Crouching Tiger, Navarro admits that “reducing the flow of cheap, illegally subsidized ‘Made in China’ goods into American markets would hit the poorest segments of American society disproportionately hard.” Protectionism is unfair to the poor.

It is not unfair for American consumers to get bargains on goods from China or other developing countries. It is not unfair to let private firms, wherever they are, compete to satisfy consumers. What is clearly unfair is to use the power of government to protect a small number of American producers, like the 2,400 American workers (at most) occupied in manufacturing washing machines, plus the shareholders (not all American) of the few domestic washer manufacturers, to the detriment of 97 million American households. (See “Putting 97 Million Households through the Wringer,” Spring 2018.)

The Trade Deficit Argument

Navarro views the persistent U.S. trade deficit as another justification for American protectionism. Instead of just “free and fair trade,” he now calls for “free, fair, and balanced trade”—that is, an end to the trade deficit. But the trade deficit is a false problem originating from a faulty economic analysis, a statistical confusion, and a sort of logical prank.

The economic error is to assume, perhaps because “deficit” is a pejorative term, that a trade deficit is bad in itself. A trade deficit stemming from the decentralized actions of importers and exporters—the former buying more goods and services than the latter sell—raises no problem per se. The United States had a regular trade deficit—or, more precisely, a merchandise deficit—until the Civil War, and a surplus during the Great Depression and the two world wars.

The error is compounded when it is further assumed that a bilateral trade deficit—a deficit with a specific country—is bad, as if every pair of countries should, or could realistically, have a zero balance in their trade of goods and services.

There is nothing intrinsically bad about a global trade deficit, which implies that net foreign investment is coming into the country. Also, there is nothing intrinsically good in a trade surplus, which implies that net capital is leaving the country. A trade deficit, however, may be bad when, like is currently the case in the United States, it is due mainly to high federal budget deficits that attract foreign purchases of Treasury bonds.

In The Coming China Wars, Navarro subliminally suggests that China is to blame for the federal budget deficit because the Chinese buy Treasury bonds. Over the past five decades, the U.S. government has proven that it is quite able to run growing budget deficits by itself, which in turn invites trade deficits. As of May 2018, Chinese holdings of Treasury bonds (no doubt mostly by the Chinese government) correspond to 7.7% of the federal debt.

Contrary to what Navarro argues, automatic adjustment mechanisms exist for trade imbalances. A trade deficit can’t grow larger than net inward capital flows. If it does, exchange rates will adjust—in the case of the United States, the dollar will lose value relative to other currencies—which in turn will reduce imports and increase exports. But foreign investors do want to invest in the attractive American economy.

Navarro falls for the journalistic canard that “net exports” (exports minus imports) reduce GDP by “simple arithmetic.” When the expression “net exports” is used, it is usually written in quotation marks, as Navarro and Autry do in Death by China, because it represents a mere statistical trick used by national statisticians to remove imports that were already included in the uses of GDP (in consumer, government, and investment expenditures). Imports have to be removed because they are not part of GDP, which is gross domestic production. (See “What You Always Wanted to Know about GDP but Were Afraid to Ask,” Winter 2016–2017.) Think about the guy on the scales who subtracts 1 lb. to factor in the weight of his shoes; his weight doesn’t change if instead he subtracts 2 pounds because on that day he is wearing heavier shoes. Likewise, American output doesn’t change because more imports are both added and subtracted. But Navarro and Autry overlook this when, in Death by China, they quickly drop the warning quotation marks around “net exports,” and substitute “trade deficit.” Hocus-pocus! They can now claim that the trade deficit reduces domestic production as a matter of accounting arithmetic.

With all due respect to Navarro, George Mason University economist Don Boudreaux was right when he posted on Facebook, “If Trump trade advisor Peter Navarro knows any economics, he’s very skilled at giving no evidence of this knowledge.”

The logical prank comes from begging the question, what is the problem with a trade deficit? It reveals unfair trade practices, answer protectionists. But how does a protectionist determine that trade is unfair? By observing that it results in a trade deficit. The evidence of a trade deficit and of unfair trade is self-referential.

The Retaliation Argument

The retaliation argument claims that protectionism and retaliation against a mercantilist country actually promote “real” free trade. Some people go so far as to say that the protectionists in the Trump administration are free-traders at heart. Such beliefs are contradicted by many declarations and actions.

In his AAM paper, Navarro eulogized NAFTA as “an almost textbook-like free-trade regime.” In Death by China, he and Autry contrast China with “our real free trade partners like Japan, Mexico, and Germany.” But the Trump administration’s tariffs have hit Mexico and Canada, which are part of NAFTA, as well as the European Union, which includes Germany. Trump specifically threatened German car imports. European countries are politically and economically similar to the United States and, as Navarro recognized in his AAM article, they and Japan, Mexico, and Canada “normally play by the rules set forth by the WTO and GATT.” Only real American protectionists would attack those countries. Yet now Navarro is one of the cheerleaders for Trump’s broad protectionist policies.

For all we know, Navarro himself is onboard with wall-to-wall protectionism. Remember that, in his opinion, “fair and free trade” has to be balanced too. That means trade will never be acceptable because there are always imbalances.

Even in the case of China, traditional “free trader” governments would think that fighting violations of WTO rules would require maintaining the WTO’s capacities to enforce them. In fact, the current U.S. administration refuses to approve replacements for departing judges in the WTO’s Appellate Body, which slows it down and will completely incapacitate it by the end of 2019.

With the protectionists in power in Washington, we now watch the amusing if not absurd scene of the Chinese government defending free trade. Last May, the Chinese ambassador to the WTO even quoted Adam Smith to his—probably mum—American counterpart. What a strange world if there ever was one!

Errors of retaliation / Trade retaliation is almost always a bad idea. First, as Adam Smith noted in The Wealth of Nations and the young Navarro concurred in his 1984 book, it rarely succeeds in opening trade; on the contrary, it risks starting a trade war in which everybody loses.

Second, retaliation is unnecessary because, one way or another, exports must always equal imports plus net foreign investment. Dollars paid for imports always come back. The foreigners who receive them in payment for their exports will convert them into local currencies. The ultimate recipients will then use the dollars to either import from America or invest in America, if only in Treasury securities, which are deemed as good as cash and pay interest.

Third, retaliation is self-detrimental. A domestic tariff (or another form of import restriction) hurts domestic consumers, who have to pay more for the targeted good regardless of whether it is imported or domestically produced. Domestic producers want protection precisely in order to charge consumers more for products. Importers reimburse in higher prices what (or most of what) foreign producers pay in tariffs. A tariff is thus a tax on domestic consumers. As British economist Joan Robinson remarked, retaliation is as sensible as it would be “to dump rocks into our harbors because other nations have rocky coasts.”

Contrary to what Navarro preaches, trade is not like war. In fact, nations or countries do not trade; individuals do, often through corporate intermediaries. Any trade is beneficial to all trading partners; otherwise, one party would walk away from the exchange. Individuals and private bodies should be left free to make their own bargains. The goal should not be to stop China from growing but, on the contrary, to not interfere with its people as they become richer and freer, just as Americans simultaneously do.

A recent analysis in the Economic Synopses of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis concludes that “a trade war with China can neither stop the decline in American manufacturing employment nor eliminate the U.S. trade deficit, but it could significantly reduce the welfare of American consumers by making U.S. imports of Chinese goods more expensive.” The same goes for trade with other countries.

Bronson Jones, the CEO of a metal products manufacturer harmed by Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs, sees them as part of a negotiating strategy. Such tariffs, he said, are “short-term pain for long-term gain” (New York Times, July 23rd, 2018). In fact, they are short-term gains for politicians in exchange for economic pain, possibly long-term, for nearly everyone else, a standard result of government interventionism.

A national government should declare unilateral free trade if it wants to act in the best interest of its citizens. Multilateral free trade is the first-best outcome because multiple countries’ citizens benefit, but the second-best is unilateral free trade. It is very risky if not outright self-defeating to use the third-best—protectionism and retaliation—in a dubious effort to reach the first-best. Just because citizens of other countries don’t have free enterprise and consumer sovereignty is no reason for our government to similarly deprive us by controlling which goods or services we import, whom we import capital from, or how we invest abroad.

Economists as ideologically diverse as Paul Krugman, a Nobel prizewinning economist, and Jagdish Bhagwati, a famous trade economist, think in terms of unilateral free trade. Practical instances of unilateral free trade can be found in the United Kingdom after the abolition of the Corn Laws in the middle of the 19th century, Hong Kong today, and the large number of national governments that currently don’t charge the maximum (or “bound”) tariffs allowed by the WTO. For example, the Mexican government applies (to non-NAFTA countries) an average tariff of 7.4% instead of the bound rate of 35% it is allowed.

The National Security Argument

The national security argument is really just a protectionist excuse. If steel, aluminum, or cars imported from, or available in, allied countries raise security problems here in the United States, then everything from food to clothes does also. Nobody can wage a war naked or hungry, after all. By this logic, the government should slap national security tariffs on these goods as well. Yet it doesn’t because policymakers realize that having foreign sources for these goods to complement domestic supply is beneficial to defense (not to mention most everything else). As the young, free-trade Navarro argued, “It is highly possible that our defense capability might actually be enhanced—not damaged—by import competition.”

We may add that future wars may be won as much with electronic wizardry as with traditional hardware. In a similar vein, Robert Work, deputy defense secretary until 2017, “argues that the West’s most enduring military advantage will be the quality of the people produced by open societies” (“When Weapons Can Think for Themselves,” The Economist, April 26, 2018). The quality of people and goods will be higher in a free society, and a free society implies freedom to trade.

It is also worth noting that national security is arguably undermined by the conflicts that protectionism creates with allied governments and their populations. The free-trade Navarro suggested this very idea in his 1984 book.

It is trivially true that any foreign country that becomes richer could represent a more serious military threat because its government can extract or requisition more resources for war purposes. But it is no less true that wealthier people are likely to be less willing to go to war because they have more to lose economically. Thus trade can help prevent war. Making pariahs of the Chinese will harm, not improve, national security.

Contrary to what Navarro now claims, American consumers of Chinese goods (or the trade deficit) don’t finance the military means of the Chinese government as much as they use Chinese resources to produce export goods for Americans. More Chinese exports to America, fewer resources left to build war machines (other things equal, of course). In the process of trade, both sides get richer. Today’s Navarro does not seem to remember the benefits of exchange that his younger self understood well.

His current focus on “protecting” U.S. manufacturing is probably as outdated from a national security viewpoint as it is from a narrower economic viewpoint. Remember that in America as in other advanced countries, two-thirds of consumer expenditures are devoted to services. Another reason why the proportion of employment in the manufacturing sector has been declining for six decades is that productivity has increased to the point that real American manufacturing output has nearly tripled since 1972. Old-style manufacturing has moved to developing countries, but complex manufacturing has progressed in America. Protecting old manufacturing amounts to “bailing out our failing industries,” as Wharton School economist Ann Harrison puts it.

Emotional and Political Arguments

Our original question was whether Navarro’s conversion to protectionism provides good reasons to share some popular doubts about free trade. It appears that the answer is no. His conversion to protectionism relies very little on economics. Instead, he seems motivated by military fears and nationalist emotions.

These motivations appear perhaps most clearly in Chapter 15 of Death by China. There, he and Autry lead a pamphleteer’s charge against what they call “China apologists.” Among their foils are “liberals” (in the American sense) as well as many “conservatives” (they don’t distinguish conservatives and libertarians) who show “a blind faith in the principle of free trade.” “It is virtually impossible to reason with them,” Navarro and Autry add. The “apologists” include the Cato Institute, the Heritage Foundation, and some “turncoat” CEOs.

Reflecting on the Wall Street Journal’s fear of a repeat of Smoot–Hawley protectionism (a concern the young Navarro shared in The Policy Game), Death by China claims “it is all so much cow manure.”

Navarro and Autry’s criticisms are especially nasty for journalist Fareed Zakaria, whose name adorns the chapter’s subtitle: “Fareed Zakaria Floats Away.” A former Time editor, Zakaria is a CNN host and Washington Post columnist. By defending China, they claim, he makes no allowance for the fact that the elimination of Chinese competition would help “our good neighbor Mexico and Zakaria’s home country of India.” “Well, Fareed,” they conclude, “that’s just plain cold. Have you forgotten your own roots and the slums of Bombay?”

Conclusion

Writing for Foreign Policy in March 2017, journalist Melissa Chan depicts Navarro as motivated by his love of media attention and his longing for political fame. He ran for public office several times, always unsuccessfully, and “morphed from registered Republican, to Independent, to Democrat, and back to Republican.” According to Chan, he is derided by well-regarded China analysts. Disregarding psychological and political speculations, one thing is sure: his arguments are not based on economic analysis.

To summarize my arguments, economics strongly suggests that the best trade policy is not to have one, to leave citizens alone to import or export as they wish. That’s true whether the country’s trading partners are free-traders or dirigistes like China. Free enterprise and economic freedom are not only efficient, they are what fairness is or should be about. There is no reason to be concerned with the trade deficit, except to the extent that it is caused by federal profligacy, in which case the solution is to solve the root cause of the problem. Retaliation only compounds other countries’ protectionism. National security is an easy protectionist excuse. Building a war economy in peace time is not acceptable in a free society.

The maintenance of economic freedom at home—which includes the freedom to import what one wants if one finds the terms agreeable—is the only individualist, coherent, and realistic policy. The young Peter Navarro seemed to understand that. Sadly, today’s Navarro does not.

Readings

- Essays in the Theory of Employment, by Joan Robinson. Blackstone, 1947.

- “How China Unfairly Bests the U.S.,” by Peter Navarro. Los Angeles Times, June 21, 2011.

- “Growth, Trade, and Deindustrialization,” by Robert Rowthorn and Ramana Ramaswamy. IMF Working Paper WP/98/60, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C., March 1999.

- “Intellectual Property and China: Is China Stealing American IP?” by Paul Goldstone with Sharon Driscoll. SLS Blogs, April 10, 2018.

- “Peter Navarro’s Journey from Globalist to Protectionist, in His Own Words,” by Erica Pandey and Jonathan Swan. Axios, June 24, 2018.

- “The Myth and the Reality of Manufacturing in America,” by Michael J. Hicks and Srikant Devaraj. Center for Business and Economic Research, Ball State University, 2015.

- “Trading Myths: Addressing Misconceptions about Trade, Jobs, and Competitiveness,” by Charles Roxburgh, James Manyika, Richard Dobbs, and Jan Mischke. McKinsey Global Institute, May 2012.

- “Trump’s Top China Expert Isn’t a China Expert,” by Melissa Chan. Foreign Policy, March 13, 2017.

- “Understanding the Trade Imbalance and Employment Decline in U.S. Manufacturing,” by Brian Reinbold and Yi Wen. Economic Synopses (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis) 2018(15), 2018.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.