Eighty-five percent of Americans have visited at least one national park. Others have seen the U.S. Forest Service’s (USFS) “The Land of Many Uses” signs for national forests or notices of entry into Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands. These areas are advertised by the agencies as being “public lands,” implying that they are owned and managed in the best interest of U.S. citizens. Yet that is unlikely to be the case.

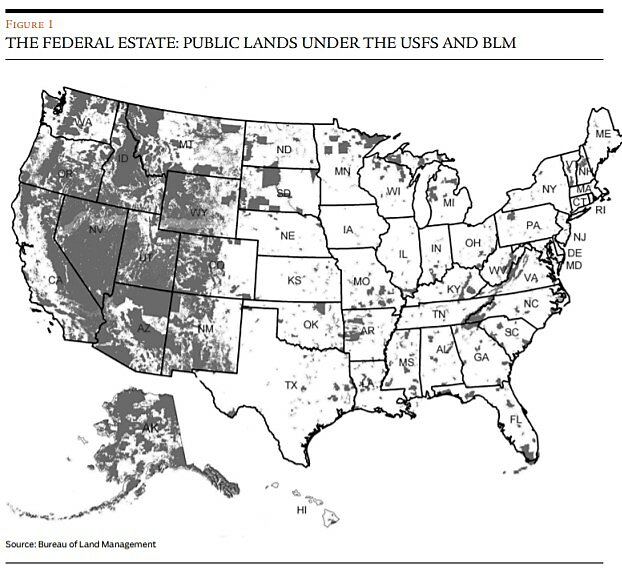

This would be of little importance except for the vast amount of land involved. In the lower 48 states, public lands encompass nearly 475 million acres, 21% of the land mass and more than the combined areas of France, Spain, Sweden, and Norway. (See Figure 1.) Adding the public lands in Alaska and Hawaii brings the total to about 640 million acres, 28% of the U.S. land area. Most citizens are unaware of just how large is the federal estate.

The Costs of Federal Land Ownership

There are several reasons why government ownership of this huge resource is detrimental to economic welfare and individual liberty. First off, it is in sharp contrast to the plans of the nation’s founders and philosophical forebears. The importance of private ownership of land for advancing individual potential and autonomy, as well as land value, was emphasized by early political economists and philosophers, including Adam Smith, John Locke, Jeremy Bentham, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Stuart Mill, David Ricardo, Edward Wakefield, and Robert Torrens. The advantages of widespread private land ownership were championed by Thomas Jefferson, who claimed that “the earth is given as a common stock for man to labor and live on…. The small landholders are the most precious part of a state.” As he toured the new country in 1835, Alexis de Tocqueville observed that being freeholders changed the way in which Americans thought of themselves and the country’s political structure. The noted historian of the frontier Frederick Jackson Turner asserted in 1893 that America ultimately was shaped by private ownership and small-farm frontier settlement as the underpinnings for democracy, an independent citizenry, and generalized economic wellbeing.

In contrast, in the more modern period, the threats of private ownership for an authoritarian government were clearly understood by Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, and Mao Zedong. They banned private property in land and placed it in state possession, jailing or executing previous owners. Even today in China, where private rights to intangible property such as stocks and bonds are tolerated, long-term, fee-simple title to land is prohibited. The state remains dominant in holding the most critical resources as its own.

From the colonial period through the late 19th century, the overriding aim of government land policies was to transfer land ownership as quickly as possible from the state to private citizens. The attraction of America for immigrants was land. And they could get it in comparatively small parcels that supported individual farms. The Homestead Act of 1862 distributed federal land in 160-acre plots for free to claimants, and between 1863 and 1920 some nearly three million homestead claims were filed for more than 435 million acres, smaller than the government’s holdings today but larger than Alaska.

A land demarcation system was created to facilitate the measurement, location, trade, and productive use of land. The frontier societies that emerged were among the most egalitarian in the world. Capital gains from land ownership and sale were the primary sources of wealth creation, and the use of land as collateral encouraged widespread participation in and growth of capital markets. Agricultural production expanded and prosperous communities emerged. Private citizens with a stake in society invested in local public goods provision, particularly education, so that the United States became a world leader in general access to a practical education. Such a society was politically stable.

The long-standing emphasis on the private acquisition of government lands, however, ended in the late 19th century. In its place came the creation of the National Forests, now comprising more than 225 million acres, and the National Rangelands, covering almost 250 million acres, along with a permanent bureaucracy for administration and short-term distribution. As of Fiscal Year 2018, the USFS has some 37,000 career, tenured civil service employees and a budget of $1.75 billion, and the BLM has over 8,000 career employees and a budget of $1.1 billion.

Lost economic value / A second reason why so much land ownership by the state is detrimental is that much of it is misallocated and dramatically under-produces, diminishing general welfare. Much poorer developing countries seek to have their natural resources provide employment and output for their citizens, but the United States locks more and more federal land away, ostensibly for preservation for future generations. There is no clear metric for assessing how those generations will benefit nor are the tradeoffs easily available for general citizens to assess. Decisions are determined by politicians and the bureaucracy in response to lobby pressures, and no party in that process bears direct costs from the associated resource allocation and use decisions.

This is not to say that areas of high amenity or cultural values should not be set aside. This description, however, does not characterize most of the federal lands. Currently, the National Park Service in the Department of the Interior administers a comparatively small 27 million acres in the lower 48 states and 80 million acres (12% of the total federal lands) in the United States overall, as national parks, national monuments, national preserves, national historic sites, national recreation areas, and national battlefields.

There are no aggregate measures of the opportunity costs resulting from mismanagement and allocation. Evidence suggests, however, that the costs could be very large given the size of the federal estate. Consider that while oil and natural gas production have jumped dramatically on private lands over the past 10 years, on federal lands output has been static or declining, even with favorable geologic deposits.

Similarly, timber production from the National Forests has fallen sharply to levels not observed since the 1930s, even though lumber prices are rising. Higher lumber prices contribute to upward shifts in housing costs that are of concern to many because of their equity implications. Poorer members of society are increasingly unable to afford to own homes.

Where comparable data exist in the Pacific Northwest, it is possible to examine output on private lands versus the National Forests. Timber harvest from federal lands has fallen, while harvest from private lands in the region is the primary source of output. Withholding timber stands does not make them more valuable. As timber stands age, they grow more slowly, block new tree growth, and become more vulnerable to disease. It is often argued that the National Forests should be more aggressively thinned than they are now to better conserve scarce western water supplies and reduce the incidence and growth of wildfires.

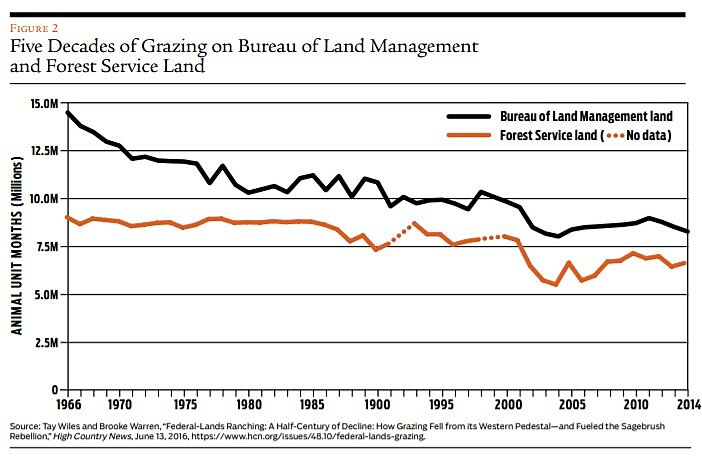

Finally, as with other productive uses, livestock grazing on federal lands has declined for nearly 50 years. The negative economic effect of reduced grazing on rangelands, particularly, is concentrated in semi-arid regions where there are few other land-use options and the federal share of land ownership is large. For example, the BLM administers 85% of Nevada, 57% of Utah, and nearly 50% or more of Arizona, Idaho, and Oregon. With greater uncertainty associated with approval and maintenance of the grazing permits that ranchers depend upon, the lands’ economic value has fallen. Ranches have gone into foreclosure or been consolidated. Rural communities tied to ranching and lumbering have withered as the economic base surrounding them has deteriorated. As a result, opportunities for the young have plummeted, encouraging out-migration to urban areas. The relative weakening of rural economies and population declines are of growing concern in policy circles.

Locking away more land / As administrative reallocation and regulatory controls have led to the fall in the productive use of federal lands, more land has been placed into various types of preservation and recreation. Is this optimal? How much land should be locked away? Only a rich country could afford to set aside so much valuable real estate. This luxury could be temporary, however, if the costs rise and become more apparent to citizens.

To get a sense of what might be at stake, consider the decision to withhold oil and gas exploration and production in the 19 million-acre Arctic National Wildlife Reserve in Alaska since 1977. With reserves of 7.06 billion barrels of oil, priced at (a comparatively conservative) $50 per barrel, the estimated opportunity costs are $251 billion, a present value of $1,141 per adult citizen. Across the entire federal lands, the costs of preserving so much land are apt to be orders of magnitude higher. Such losses likely affect gross domestic product growth, employment opportunities, and welfare for the overall population.

With competitive markets, private land is reallocated across uses routinely as prices shift on the margin. Land moves to its highest-valued use. Critical private lands needed for public infrastructure investment, preservation, or protection of amenity values can be acquired by the government. Proposed expenditures can be weighed against alternatives. Political/bureaucratic allocation and management of lands already owned by the state, however, do not work in this manner. Multiple constituent groups, ranging from environmental and recreational organizations to historic users—ranchers, timber companies, minerals and oil and gas producers—appear before congressional hearings and before the agencies to lobby for their favored policies. Outcomes depend upon the strength of the lobby group, whether they face competitors, and how politicians and agency officials respond to them. Cost–benefit analysis of bureaucratic decisions, where used, often is not transparent and agency decisions are cloaked in public-goods rhetoric. In this setting, citizens have little information to assess the net effect of the decisions made by the bureaucracy that manages the federal lands.

A third reason why federal land ownership is damaging is that the allocation and reallocation of so large a resource stock through the political/bureaucratic process is socially divisive. Reallocation is not routine, but lumpy. Constituent groups compete to enlist the coercive power of the state on their behalf. Losers, unlike sellers, are not compensated, and winners, unlike buyers, do not pay for the value of the resource. The losers resent the outcome and blame the winners, while the winners characterize past users and uses as inconsistent with the public interest. This process undermines social cohesion and civil discourse, both of which are essential for a functioning, stable democracy.

How Did the Federal Government Reserve so Much Land?

To understand how the federal government came to withhold so much land given the past emphasis on private ownership, it is useful to consider the U.S. settlement process in the late 19th century. As the frontier moved west of the 100th meridian, far different conditions were encountered from those to the east. The land was more rugged and semi-arid, making it less economically viable for small farming. Logging, ranching, and mineral production were more appropriate economic uses. Land laws such as the Homestead Act could have been modified to allow for much larger, non-farming distributions, but they were not.

At the time, such changes in the laws seemed to limit opportunities for further land ownership by homesteaders, and there was no political support for them. In his Report on the Arid Lands of North America made to Congress in 1879, John Wesley Powell called for minimum 2,560-acre homesteads—16 times greater than the size of standard homestead allotments—to address the problem, but nothing came of it. In the late 19th century there was no conclusive evidence that small farms were not suitable for the region, especially if settlement changed the climate, if “rain follows the plow,” if new dry farming techniques could offset aridity, or if sufficient irrigation networks could be developed. In light of this, there was no concerted action in Congress to change the laws.

By the turn of the 20th century and advent of major droughts, however, it became clearer that only irrigation would save the small-farm objective. Congress was intensely lobbied to provide for subsidized irrigation via the 1902 and 1906 Reclamation Acts. New federal dams and irrigation canals diverted water from western rivers, such as the Snake, Yellowstone, Salt, and San Joaquin, to adjacent lands for homesteading. Indeed, after 1902, the number of new homesteads jumped to totals larger than in any earlier period. Range and timber lands, remote from rivers and rugged, were not much affected by reclamation. Ranchers and timber companies continued to use them. These parties faced economies of scale, requiring operations far larger than 160 acres.

Withdrawing property rights / Ranchers claimed homesteads around water sources and then fenced the surrounding government rangeland to control their herds. The General Land Office that later became the BLM and was funded to process homestead claims opposed these enclosures and removed the fences. Grasslands that had been previously protected by fencing and livestock association patrols against trespassing reverted to common-pool resources. Overgrazing followed. By the 1930s, the Departments of Agriculture and the Interior pointed to rangeland depletion as indication of the need for government management. In 1934 the Taylor Grazing Act was passed, removing the rangelands from homesteading and placing them in permanent management by the new grazing service that became the BLM.

Timber companies faced similar constraints. Unable to secure forest lands legally, timber operators hired entrymen to act as homesteaders to file claims and purchase them under various land laws from the 1880s through the turn of the 20th century. Homestead plots were then consolidated into larger timber parcels, but there was always the possibility that government inspectors would discover the false claims and cancel them. The added costs of staking fake homesteads and their assembly, as well as the uncertainty of securing private property rights, delayed titling by six years or more. This ambiguous property rights condition contributed to rapid, open-access harvesting and timber theft, as noted by conservationists and government officials at the time the land laws were being revised. They failed to recognize that the culprit was the lack of property rights, not harvest practices otherwise intrinsic in private production when rights were secure.

The withdrawal of federal range and timber lands from private claiming was spearheaded by members of the first environmental or conservation movement. Early conservationists and their political and bureaucratic patrons challenged the long-standing notion that private property rights and markets were key elements in the development of the American state, economy, and society. They saw private markets as inherently wasteful without the remedy of government ownership and management by professionals.

By the late 19th century, increasingly many such professionals were employed by the federal government as both the size and scope of the federal role in the economy expanded. Federal civilian employment was just over 130,000 in 1885 but grew by 258% to nearly 470,000 by 1913. A merit-based, independent civil service gradually acquired regulatory mandates, job tenure, and higher salary growth relative to the private sector.

Source: Tay Wiles and Brooke Warren, "Federal-Lands Ranching: A Half-Century of Decline: How Grazing Fell from its Western Pedestal—and Fueled the Sagebrush Rebellion," High Country News, June 13, 2016, https://www.hcn.org/issues/48.10/federal-lands-grazing.

To advance their objectives, federal agencies developed political agendas. The same advocates for retention of federal lands became leaders of the bureaucratic agencies that managed them. Private property rights and constrained decision-making did not fit within their regulatory plans that called for rational, scientific management. Bernhard Fernow, head of the Division of Forestry in the U.S. Department of Agriculture from 1886 to 1898, and Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service, 1905–1910, were major leaders in the effort to create the National Forest Reserves, later the National Forests. They were assisted by outside lobby groups such as the Society of American Foresters, the American Forestry Association, and the National Forest Congress. Through their efforts and the backing of presidents William Harrison, Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt, the Forest Reserve Act was passed in 1891, the Forest Management Act in 1897, and the National Forest Transfer Act in 1905, which moved the forest reserves from the Department of the Interior to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Fernow and Pinchot, educated in Germany and France respectively, advocated "scientific" forest management whereby harvest rates were to equal growth rates to achieve sustained-yield. The conditions underlying this "rational" management of European forests could not have been more different from those of North America. The United States was rapidly growing and demand drove rising lumber and timber (stumpage) prices. Interest rates were high. By the latter half of the 19th century, the United States was endowed with three major commercial old-growth timber stands—the white pine forests of the upper Midwest and Great Lakes, the yellow pine forests of the South, and the Douglas Fir forests of the Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies. The rapid private harvests in the United States to meet growing demand and shifting domestic supplies across the three regions were instrumental in shaping the views of early advocates of sustained-yield management and retention of government lands.

In particular, Fernow, Pinchot, and others pointed to what seemed to them to be the excessive cutting of private timber stands in the Upper Great Lakes as evidence of the need for retained government ownership in the Pacific Northwest. They argued that timber companies harvested too rapidly, unconcerned about future supplies. Neither they nor subsequent sympathetic historians of the conservation movement have provided data to assess these claims, but there is reason for skepticism. U.S. lumber and timber (stumpage) price patterns between 1870 and 1930 do not reveal myopic behavior in private harvests. If companies cut their timber stands in ignorance of true supply conditions as alleged, once accurate supply information became available, prices that were too low would jump and companies would cut back harvest. But there is no evidence of such price shocks or production adjustments. Prices generally moved smoothly over the period, implying that the private market was fully incorporating available information about timber supply and demand.

Conservationists and subsequent historians have pointed to timber theft in the Pacific Northwest as evidence of rapacious behavior by private timber companies. But as noted above, the problem lay in the politically inflexible land laws that raised the costs of obtaining title to land. Similar arguments by conservationists were made for the retention and management of federal range lands.

In securing enactment of National Forest legislation and the Taylor Grazing Act, proponents co-opted the very interests—timber companies and herders—that would have benefited from more liberal land allocation and that might have organized as effective political counters. Pinchot called for multiple use of federal lands rather than complete preservation. He and other conservation leaders offered timber companies harvest leases and subsidized access to forest lands. For the first time, those companies could secure the legal right of entry to forests through timber harvest leases that they had not been able to obtain under the old land laws. Similarly, herders were offered renewable grazing permits within newly created grazing districts.

What timber companies and herders failed to anticipate was that this was a Faustian bargain. Later, new demands for federal lands and subsidies emerged for species preservation, recreation, and other environmental applications that meshed with the long-term management objectives of the BLM and USFS. As these constituencies appeared, previous access and subsidies for production from federal lands became less secure and subject to continued administrative reallocation and regulation. Timber companies and ranchers did not recognize that the federal lands were constituent-group lands.

Where Does This Leave Us? Are There Remedies?

The withdrawal of federal lands from private claiming and titling began with the General Revision Act of 1891 and continued with the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 and subsequent legislation, including the Multiple Use, Sustained Yield Act of 1960 and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976. These laws assign broad access and use control to federal bureaucracies. They represent a fundamental shift in the roles of private property rights and the state, with implications beyond federal holdings.

With the founding of the republic, reliance was placed on individual decisions regarding land use and allocation, decentralization, and a minimal role of the state. With the reservation of immense amounts of land by the federal government and permanent administrative management, reliance has been transferred to an unelected, professional, and tenured bureaucracy with centralized decision-making authority. The state has been elevated over the market. The argument made at the time of this transformation was that market failure required intervention in the public interest. This same argument drives expansion of federal and state environmental regulation of private property rights and land use in the 21st century.

The historical record regarding federal lands is clear that the inability to acquire property rights under the land laws to the remaining federal estate has become a major problem. Although there can be externalities and market failure associated with private decision-making when property rights are incomplete, the direct remedy would be to make property rights more complete as Ronald Coase argued, and not resort to government ownership, regulation, or taxes. Externalities are more likely to occur with resources that are difficult to bound and observe, such as the atmosphere or groundwater, rather than surface land. The concept of externality is an elastic one that can be made to justify almost any state intervention. Whether or not such actions are defensible requires assessment and evaluation, rather than uncritical acceptance of the call for greater intrusion into the economy and society by an ostensibly benign bureaucracy operating under multiple-use rhetoric.

Is there a remedy? In a currently wealthy country where interests vary, those parties that favor preservation of enormous areas for a variety of reasons are likely to sustain the present situation. Their objectives generally coincide with those of agency officials whose regulatory mandates are advanced with sustained-yield approaches. Moreover, many agency officials are trained biologists in forestry and range management. They are only tangentially proficient in oil and gas production, minerals output, livestock raising, and timbering. These are economic activities that compete with preservation goals.

Private decision-making over resource use generally would not coincide with broad bureaucratic discretion. Influential environmental lobby groups for the most part applaud the existing arrangement. Moreover, those in communities close to federal lands that value low-cost access for hunting, fishing, and hiking also have their objectives met. This is politically based open access that can have predicted negative results for the resource stock.

Even so, a coalition of agency officials, environmental lobby groups, and recreation interests is a formidable one, regardless of the aggregate economic and social costs of the status quo. Only as costs of the contemporary arrangement rise and as competing interest groups appear will the general citizenry be made more aware of the negative consequences of bureaucratic management in the name of preservation and future generations.