With the U.S. economy growing at a zombie-like pace, we’re now hearing whispers that American-style capitalism is passing away. A recent paper by Credit Suisse analysts Michael Mauboussin, Dan Callahan, and Darius Mjad indicates that more than half of all U.S. publicly traded companies have disappeared from stock market listings in the last 20 years. The authors note that the disappearances are not explained statistically by growth in gross domestic product or other relevant independent variables when they model the count of publicly traded firms. The same phenomenon is not seen in other parts of the industrialized world. Put another way, something else is going on in the United States.

In 1997 there were 7,355 exchange-listed firms, according to Mauboussin et al.; today there are less than 3,600. According to their estimates, there’s currently a 5,800-firm shortfall, if historical trends had continued. But though the number of market-listed firms has gotten smaller, the firms themselves have gotten much bigger and older; the average market-capitalized value of listed firms has increased 10-fold and the average age of listed firms has risen 80%.

What’s going on here? Could the disappearance of exchange-listed firms be evidence of the rise of big-firm capitalism described by William Baumol, Robert Litan, and Carl Schramm in their 2007 Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism, and the Economics of Growth and Prosperity, in which they argue that large firms have distinct advantages in global market operations? Or could it be that, among other advantages, large firms benefit from regulatory economies of scale, as Kevin Murphy, Andrei Schleifer, and Robert Vichny described in a 1993 paper and Richard Wagner in a 2016 book?

Big firms, big markets / Baumol, Litan, and Schramm offer a taxonomy as well as a theory of capitalism’s evolution. They first describe bad systems in which national economies are formed by way of state-guided capitalism in which national governments pick winning firms, industries, and sectors. By way of subsidies, loans, or other special treatments, governments then seek to give a predetermined advantage to the selected firms or sectors. We see an example of state-guided capitalism in the current U.S. government’s support for certain forms of renewable energy (ethanol and solar) and low-emission automobiles, the extensive government management of health care, the regulation of housing finance, and the government direction of agricultural markets.

Oligarchic capitalism, the second bad category identified by Baumol, Litan, and Schramm, is generally observed in countries that lack an independent judiciary as well as predictable definition and enforcement of property rights. In these situations, strong families emerge as the owners and protectors of wealth, sometimes in collusion with government dictators and leaders or through extralegal means, such as with the mafia. In recent years, we have observed oligarchic capitalism emerge as previously socialist countries became transition economies. In those cases, oligarchic capitalism has been termed “crony capitalism.” The absence of strongly evolved market-friendly institutions is part and parcel of these capitalistic schemes, where individual ownership of assets and trade in major products and services are dominated by a small number of individuals or families.

Big-firm capitalism is an important third category. It is not necessarily bad; in fact, it is fundamental to the formation of good capitalism. The big firms are large enough to exploit ultimate economies of scale and scope. They operate in fully national and global markets and in doing so take up the production of newly developed products and services, extending them to the four corners of the earth. Baumol, Litan, and Schramm see this category as a principal component of the currently evolving U.S. economy.

In some cases, the big firms are the result of rapidly growing entrepreneurial firms, which represent the three scholars’ final category. Entrepreneurial capitalism brings radical, transformative innovations and from which fundamentally different products and ways of doing business emerge. Current examples include transportation services Uber and Lyft, which demonstrate how small, innovative firms can emerge and—following a big-firm capitalism pattern established by Facebook, Google, and Amazon—quickly become large global players.

Baumol, Litan, and Schramm’s theory of American capitalism requires an economically healthy operating environment for high-growth small firms and for big-firm operators that convey newly emerging products and services to global markets. However, the authors do not deal with the political interaction and rent-seeking that occur as big firms gain dominant positions in their industries. Nor do they deal explicitly with big firms’ demand for specific regulations that will increase or stabilize the firms’ profitability and cement their dominant position.

Clearly, it is possible for big-firm capitalism to turn bad. Put another way, it is possible for a small number of big firms to have disproportionate power in influencing the direction taken by a political economy. These firms can also be protected from competitive entry by regulatory mandates that raise rivals’ costs and reduce the flow of consumer-valued goods and services to the marketplace.

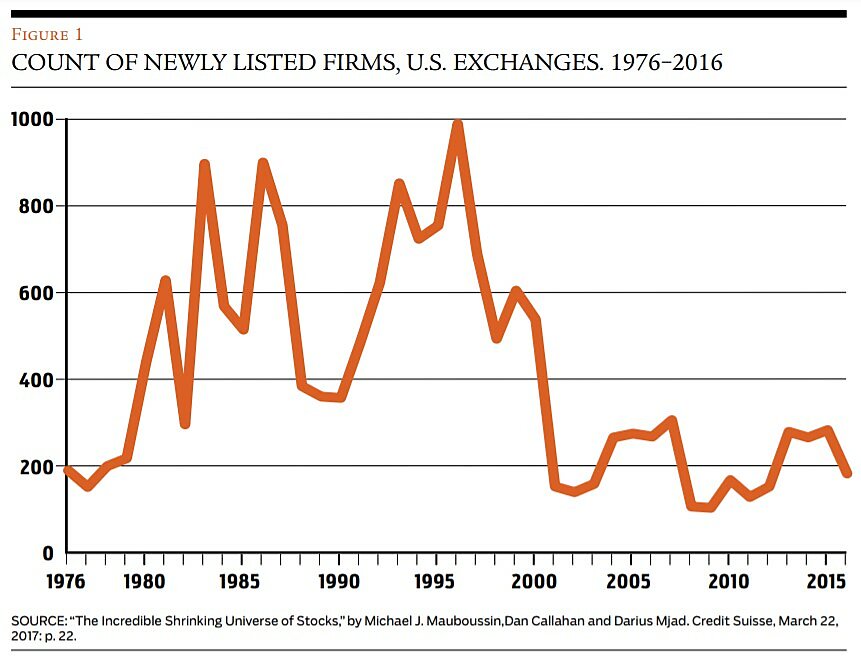

What data may tell us / Mauboussin, Callahan, and Mjad tell us that the number of U.S.-listed firms has fallen by 50% since 1979. The count of newly listed firms is an obviously important metric of the vitality of a capitalist economy. After all, financial markets provide access to capital and thereby nurture the growth of capitalist systems.

The authors also report that the average market-capitalized value of listed firms has risen from $620 million in 1979 to $6.8 billion in 2016 (both in 2016 dollars). Simply put, today’s marketplace is dominated by big firms. Baumol, Litan, and Schramm should be pleased by the accuracy of this part of their 2007 analysis.

In addition, the average age of listed firms has risen from 10.9 years to 18.4 years. The big firms seem to be more durable and perhaps are better protected from competition. These data support the notion that entry barriers may be higher; the data also support indirectly the notion that regulation matters.

But there may be something else going on, something Baumol, Litan, and Schramm did not consider. As shown in Figure 1, new firm listings generally rose from 1976 to 1996 and then plummeted around the time of the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley corporate governance and accounting legislation.

Obviously, something else could be affecting the listing decline, but it is hard to dismiss Sarbanes-Oxley out of hand. It significantly raised disclosure requirements and personal liability for corporate officers and directors, which in turn made the decision to become a listed firm far more costly. In commenting on the possible Sarbanes-Oxley effect, Mauboussin, Callahan, and Mjad indicate that the legislation could have been an influence, but that the decline in the total number of listed firms was underway prior to 2002. However, when just new listings are examined instead of total firms, it seems clear that 2002 is a strategic date.

In their 2009 financial markets analysis of the costs and benefits of Sarbanes-Oxley, Yael Hochberg, Paola Sapienza, and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen examined lobbying activities by individual investors, large investors, and corporate insiders. They found evidence of higher abnormal returns for firm portfolios where small and large investors lobbied for final Sarbanes-Oxley rules, as well as for firms where insiders lobbied against the same rules. Probing deeper, the three authors found that insider opposition was higher for firms where there was evidence of higher agency cost and relaxed executive behavior.

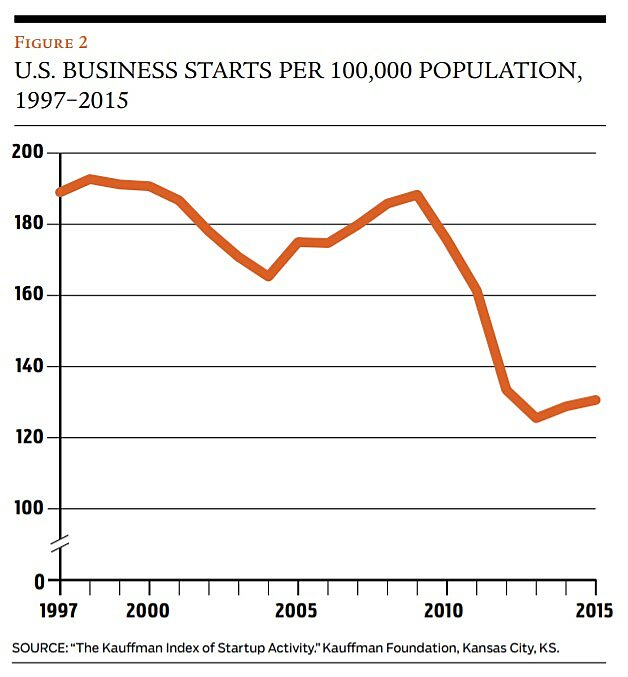

Data from the Kauffman Foundation on new business starts adds another dimension to our discussion of entry in America’s newly forming industrial organization. Figure 2 shows the trend in newly formed firms. Once again, fewer people are knocking at the door. In 2000 there were approximately 190.7 new starts per 100,000 population. By 2015 the count had fallen to 130.6, more than a 30% decline. With the start-up rate falling, all else equal, there will be fewer new listings on stock exchanges.

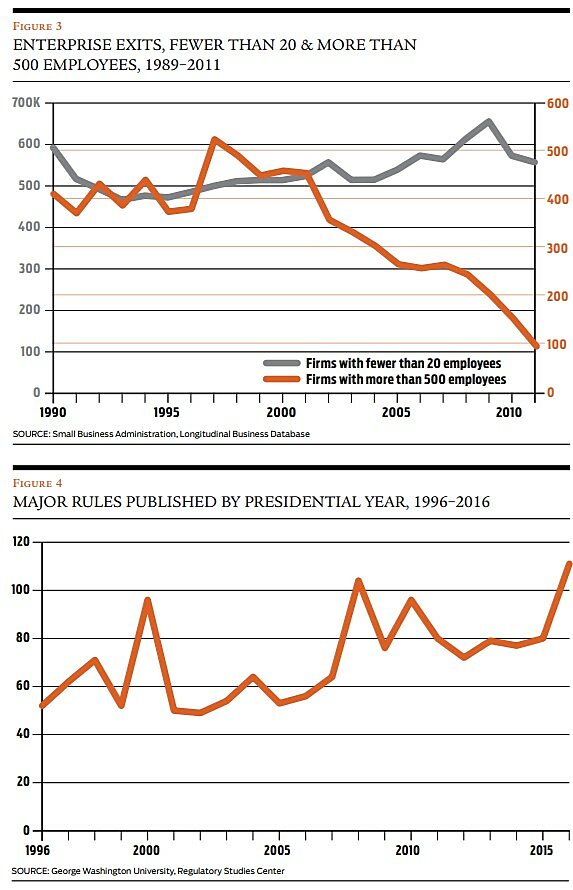

If entry is affected, what about exits? A Small Business Administration data set (ended after 2011) on the dynamics of the U.S. economy supports the notion that big-firm capitalism is somehow better insulated from competitive entry and other marketplace hazards. Figure 3 reports exit data—deaths of firms—with more than 500 workers and with 20 or fewer workers. Note that exit activities for the two categories follow a similar pattern from 1989 until about 2000. At that point, big-firm exits plummet.

With fewer exits across time, the average age of incumbent firms will rise, just as reported by Mauboussin, Callahan, and Mjad. Taken together, the three data sets—newly listed exchange firms, new starts, and exits by larger and smaller firms—describe the rise of big-firm capitalism where the larger firms seem to be insulated from competitive entry and other marketplace hazards that would cause them to fail. The data tell us that since the year 2000, fewer firms are being started and fewer yet seek to be publicly owned. The data suggest that regulation matters.

Regulatory advantage / We know there are economies of scale in managing regulations that have a high fixed cost component. We also know that there are economies of scope for firms that build lobbying networks across a large array of regulatory and other government agencies, nationally and internationally. How might this figure into the story? I contend that big firms benefit relatively from the adoption of major regulations—those that have a compliance cost of at least $100 million annually imposed on the economy. By this I do not mean that larger firms are lobbying for high-cost regulations, but rather that when major regulations befall them, larger firms generally are able to carry the load with greater ease than their smaller competitors. All else equal, the larger firms are less likely to exit the economy. Those thinking of entering with a new business are less likely to pay the price.

When major regulations befall them, larger firms generally are able to carry the load with greater ease than their smaller competitors.

The empirical element of the argument is seen in the annual count of major regulations (those with compliance costs of $100 million or more) adopted in recent years. Figure 4 shows the count for the years 1996–2016. Obviously, the count of major rules has increased systematically since 2000, and though not shown in the figure, the count is cumulative. That is, each major rule imposes at least $100 million in annual costs on the economy for as long as the rule is in force. It is my hope that this picture and the foregoing discussion will help to form refutable hypotheses for testing competing explanations for America’s disappearing capitalism.

Final thoughts / I worry that America’s regulatory-induced big-firm capitalism operates as part of a sleep-walking economy, where GDP growth is weak and the prospects for widespread wealth creation are less than stellar. While many forces interact to yield economic life, it seems clear that regulation is one of the major factors that influence the big-firm-dominated industrial organization.

With that in mind, I end this article with some sage advice from Wealth of Nations:

The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order ought always to be listened to with great precaution and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.

We are thus advised to beware of capitalists who seek and obtain advantage by way of government regulation.

Readings

- “A Lobbying Approach to Evaluating the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002,” by Yael V. Hochberg, Paola Sapienza, and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen. Journal of Accounting Research 47(2): 519–583 (May 2009).

- Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism, and the Economics of Growth and Prosperity, by William J. Baumol, Robert E. Litan, and Carl J. Schramm. Yale University Press, 2007.

- Politics as a Peculiar Business: Insights from a Theory of Entangled Political Economy, by Richard E. Wagner. Edward Elgar, 2016.

- “The Incredible Shrinking Universe of Stocks,” by Michael J. Mauboussin, Dan Callahan, and Darius Majd. Credit Suisse Global Financial Strategies, 2017.

- “Why Is Rent-Seeking So Costly to Growth?” by Kevin Murphy, Andrei Schleifer, and Robert W. Vichny. American Economic Review 83(2): 535–556 (Fall 2016).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.