All is not as it appears when it comes to the regulation of prices. Rules ostensibly created to protect consumers more often than not effectively serve the interests of the sellers. For instance, many states require that gasoline prices must be easily visible from the street, cannot be changed more than once a day, and must be above wholesale cost. While all this is done in the name of protecting the consumer, economic theory and abundant empirical evidence show that these requirements dampen price competition, causing prices to be higher than they otherwise would be. Gas station owners lobby vigorously in defense of these laws, confirming who they really help.

It turns out that the rules that govern negotiations between video programming networks (both broadcast television and non-broadcast networks) and the cable and satellite distribution systems (commonly called distributors) are similarly harmful to the market and serve to stifle programming innovation and diversity. This is especially harmful to the small, independent networks—that is, networks not affiliated with a national broadcaster, a major studio or entity owning numerous satellite or cable channels, or a multi-channel video programming distributor.

The Industry

The amount of available video offerings has grown exponentially over the last four decades. In the early 1980s, most cable packages offered the local broadcast stations and a handful of non-broadcast networks. After midnight, most television stations went dark, a concept youth today find difficult to comprehend.

Today, of course, there are hundreds of video programming networks. Tens of billions of dollars are spent each year producing and acquiring the rights to shows, movies, sporting events, and myriad other types of content for distribution. Over time there has been massive consolidation in the cable and satellite TV industry. Today there are four major distributors in the United States through which most households get their video programming: Comcast, Charter, AT&T/DirecTV, and DISH. There are also a few mid-sized players like Verizon, Altice, and Cox. Despite the recent trend toward "cord-cutting," most people still access video programming networks via a cable or satellite distributor.

Two major factors drive distributors' costs: the capital and service costs for deploying and maintaining their distribution systems, and the cost of acquiring the content they provide via their service.

Distributors negotiate carriage rights with the programming networks and in most cases pay them a per-subscriber "carriage fee" per channel for their programming. Programming networks make their money both from the monthly fees from distributors and from the advertising they sell on their channels.

A network wants to be in as many homes as possible and attract as many viewers as possible. The more viewers it has, the more it can charge for advertising and the more it can demand in subscriber fees.

The vast majority of the successful channels are members of networks "families." Sometimes these are owned by one of the distributors: for instance, Comcast owns NBC, CNBC, Bravo, E!, and a few other networks. Large multimedia companies own suites of networks: Disney owns ABC, Lifetime, A&E, the Disney Channel, and ESPN, along with all of its sister networks. Discovery, Fox, Viacom, Time Warner, A&E, and AMC are other multimedia companies that have multiple networks. These entities negotiate the carriage fees for their entire lineup of stations at once, as a package.

With only a handful of cable and satellite distributors dominating the market, the major distributors can act as an oligopsony (i.e., a small collection of buyers who, together, dominate the market) and leverage their collective market power to pay prices that would be lower than if there were real per-channel competition. An effective oligopsony would result in fewer program networks and fewer programs would be made, but—as I'll explain in a moment—the market currently does not function that way.

Added to the lack of true per-channel competition, there is no reason to believe much or any of the lower costs to the distributors would be passed on to consumers: the lower cost to acquire networks results in higher profits for the distributors.

What mitigates this suboptimal outcome—for the most part—is that the oligopsonistic distributors have to negotiate with a small group of multimedia companies that own most of the networks and function much like an oligopoly. Approximately 90 of Nielsen's 100 most-watched channels are owned by one of the major multimedia companies. Oligopolies—much like monopolies—extract higher prices from buyers and concomitantly sell less than the efficient amount. But in this market the programming conglomerates may actually sell more than the efficient amount via their insistence upon the carriage of their entire bundle of networks, including lesser-rated networks that are still paid far more than their independent, comparably rated competitors.

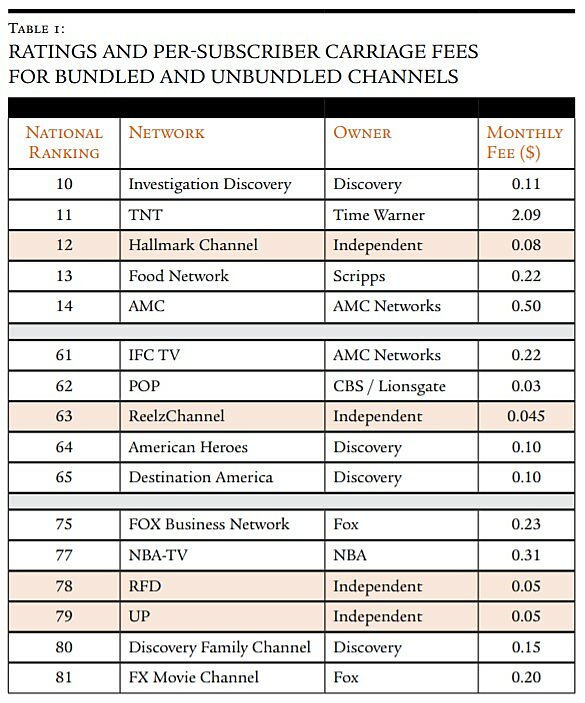

Table 1 compares the fees paid by distributors to selected independent channels as well as to comparably rated channels owned by oligopolies. The table makes clear that ratings and household delivery do not directly translate into the value of subscriber fees that distributors will grant to independent networks. The four independent networks shown in the table receive a fraction of the monthly subscriber fees paid to networks of similar or lower Nielsen ratings owned by large multimedia companies. The bargaining power of the large programming conglomerates plays an important role in determining subscriber fees and continued carriage of many programming networks. They effectively amplify their bargaining power by bundling multiple channels with a highly rated channel like ESPN.

While oligopolies and oligopsonies by themselves can lead to suboptimal outcomes, taken together—a situation economists call a bilateral oligopoly—each side's market power is tempered by the other, and the net result often approaches the efficient market outcome. Such an outcome is good for consumers, as they get access to what might be construed as the "right" amount of programming the market wants while not paying too much for it. And it's good for most networks, too, because their collective market power gives them a better outcome than if the cable and satellite distributors could exert their oligopsony powers unchecked.

Independents and MFN

This works for the program content companies with multiple network offerings that are part of the oligopoly, but it doesn't work out well for independent networks whose rights are sold alone by their company, unbundled with any other offerings. The current situation makes their existence precarious.

They are most emphatically not a part of any oligopoly: they have no market power themselves and would not add any discernible market power to the oligopoly. Instead, they find themselves negotiating by themselves against the cable and satellite distributors. What's more, they must do so burdened by the terms intended to govern the bilateral oligopoly—particularly the so-called "most favored nation" clause (MFN)—that work to their detriment.

MFN is a concept borrowed from international relations and its use goes back centuries. Fundamentally, an entity receiving this benefit is accorded the same privileges given to other trading partners—or in this case, other customers. In the context of television, it means that any price or provision a seller provides to one buyer must be made available to other buyers. There are a variety of MFNs, including the predominant one used with independent networks. Economists refer to this MFN as an unconditional MFN because the distributor receives a benefit—the lowest price and best terms—without giving any consideration in return.

In the current video programming market, this means that the price a cable or satellite distributor pays a program network has to be made known to other distributors as well, and those other distributors must have the option of paying that price if they choose to do so. If Comcast pays the Tribune Corporation 13¢ a month per customer to carry the independent network WGN on its system, Tribune has to let every other distributor pay that same rate as well.

If Charter told Tribune it only wanted to pay a dime a month to carry WGN, but in return Tribune would get a favorable channel placement for WGN, the loss in revenue for Tribune would be much more than a 22% reduction in monthly rights fees from that one cable company. All distributors with an MFN would get to reduce their payments by the same amount and on the same effective date, and they would not have to match the favorable channel placement.

MFNs often implicate more than carriage fees; they can affect other important non-monetary provisions such as whether a network is carried in high or standard definition, its channel placement and service tier (e.g., basic, extended, etc.), channel guide menu placement, and whether and under what conditions a network can provide content to "Over The Top" (i.e., internet-based) distributors. Some video distribution contracts involving independent programming networks even impose an MFN on MFNs.

At one level, this arrangement would appear to give an independent network a modicum of leverage: a rate reduction sought by only one distributor has a magnified effect on a network's revenue, and the distributor knows that the network simply does not have the option of acquiescing because the cost to the network of doing so would be too high. Essentially, the MFN acts just like leverage does in an investment: it amplifies the economic losses from a reduction in monthly payments, undermining any security in existing agreements.

However, that leverage is a double-edged sword: a distributor can also choose to simply not negotiate with an independent network, make a legitimate threat to do without it, and drop the network entirely. A distributor might have trouble doing without Disney/ESPN's channels, but it can do without an independent network like rural issues–oriented RFD and not engender meaningful consumer unrest. Substantial barriers to substitutability among distributors mean that consumers are very unlikely to seek out a favored independent network carried on a different distribution system. In short, changing providers is a hassle and few people will do so for an RFD, or any other single station for that matter.

The primary reason to have an MFN is that it helps to enforce the bilateral oligopoly. Oligopolies often dissipate because one or another member cheats the cartel and sells at a lower price, but the MFN prevents that from happening. However, the oligopolistic cartel is not in the best interests of independent networks or their viewers, as it gives distributors too much power over the independent channels.

The independent networks have no market power—they're too small by themselves—so they get hurt by the oligopsony that's strengthened by the MFN and its market-wide control of price and other essential business terms. In short, MFNs act as an effective substitute for collusion among the large distributors that accomplishes the same result—to the detriment of the independents.

MFNs also preclude any sort of creative pricing arrangement. For instance, an independent network may want to make a deal with Verizon whereby the independent accepts a lower carriage fee in exchange for the network being featured prominently in the "skinny" video programming packages that Verizon markets to tens of millions of wireless customers who use iPads and smartphones to access video. However, the MFN precludes such a combination because other large distributors would demand the same low carriage fee on all their platforms—while forgoing the other part of the bundled offer. (Of course, this specific example is almost irrelevant these days because the contracts of most independent networks explicitly prohibit the stations from offering their content in real-time to distribution vehicles like Hulu, Netflix, or other streaming venues.)

The academic literature on MFNs suggests that they do lower the transaction costs of reaching an agreement while also reducing the risk of a lack of agreement between buyers and sellers, a point made succinctly by Martha Samuelson, Nikita Piankov, and Brian Ellman in a report published by the Analysis Group. However, Bill Toth, writing in the Columbia Science & Technology Law Review, finds that MFNs can result in suboptimal monopolistic outcomes if there is an uncoordinated group of independents that are not a part of the bilateral monopoly. Essentially, the presence of network effects and economies of scale in the market serve as a natural barrier to entry, discouraging new channels and innovation.

What to Do?

In short, economic theory indicates that the strictures in place to strengthen the powers of the oligopoly result in an optimal market outcome in the negotiations with the oligopsonistic multimedia companies. But those strictures yield a suboptimal result when the oligopolies are negotiating with independents: the price they arrive at is suboptimal, which results in fewer independent networks and fewer choices for consumers. An unfortunate additional byproduct is that no commensurate savings accrue to consumers.

The evidence supports the theory. The independent networks receive significantly lower carriage fees compared to networks with similar or lower ratings that are owned by large multimedia companies with multiple other networks or networks that are vertically integrated with a large distributor.

How can this be fixed? One way would be to simply tell the independents to bow to reality and form their own coalition, or else nudge them to align (or be acquired) by one of the large media conglomerates. But the former won't work at present; there simply aren't enough independents with sufficient combined ratings for this to work well, despite the healthy ratings of a number of independents. The latter isn't exactly an ideal situation either. If the only avenue of success for a new network is to sell itself off to one of the large media companies, it's not clear that would bode well for innovation in the sector. While such a strategy works for internet startups, there are myriad different potential buyers for such entities, and not just a handful of oligopolists.

MFNs act as an effective substitute for collusion among the large distributors because they establish market-wide control over independent channels' prices and other essential business terms.

There is no realistic hope that the video distribution market will be disciplined by significant competitive entry. The legal and economic barriers to entry are too high for major new cable or satellite systems to enter the scene on a national basis.

Nor will Over the Top internet-based delivery overturn this closed system because there has been no meaningful entry into the distribution side of the Over The Top market. Instead, the current oligopolists are taking control of Over The Top. Large distributors often significantly restrict independents from distributing their content via alternative distribution methods, enforced through MFNs.

The logical way to fix this closed market is to simply eliminate unconditional MFNs, or at the very least end or dramatically limit their use against independent networks. Allowing the additional lever of MFNs to enhance market power for the distributors that already have a surfeit of it makes little sense and hurts the independents. It also dampens the incentives for new networks to be formed, except for those conceived by the established multimedia entities. The Federal Communications Commission has considered such prohibitions, but has yet to take such a step.

While a free and unfettered market should be preferred whenever possible, an imperfect market—such as one with a discrete number of buyers and sellers, like the market for video programming—will not necessarily lead to the economically efficient outcome. In such a situation the regulator should step in and try to nudge the market players toward something closer to an efficient outcome, using as light a touch as possible. In this market, that would entail eliminating unconditional MFN clauses, or at least prohibiting their application to independent networks.

Promoting multiple, diverse independent voices has been a cornerstone of U.S. communications policy since the enactment of the Communications Act in 1934. Yet today's trends are headed in exactly the opposite direction: media consolidation has been occurring at an ever-increasing pace, as witnessed by transactions such as AT&T's acquisition of DirecTV and its proposed acquisition of Time Warner, Comcast's acquisition of NBCU, and the recently announced acquisition of Tribune by Sinclair, to name just a few.

In the national video marketplace, barriers to entry are extremely high. In addition to raising the tens of millions of dollars necessary to obtain or develop programming, a new network needs to obtain the necessary carriage agreements with all of the major distributors. A programming network cannot be national in scope unless it achieves economic terms of distribution with all of the large distributors, because delivery of video to the home is not readily substitutable. This closed distribution market restricts consumer choice to live linear programming from the large incumbent companies. Otherwise, consumers are forced to wait for access to recorded programming, also provided by incumbents on their video-on-demand systems. The tight arrangement among the major players in the video distribution industry also limits competition from new entrants such as independent programming networks. Broadcasting directly via the internet is a nascent business that one day may disrupt the large cable companies, but at the moment the potential reach—and revenue—from such a strategy lag what is achievable via cable or satellite.

As a result of these and other marketplace factors, entrepreneurs are starting fewer new independent networks and the existing ones are increasingly being acquired or going out of business. Ed Conard, the founder of Bain Capital, pointed out in his book Unintended Consequences that a major hindrance of today's economy is that a growing proportion of savings is seeking safety first and foremost. The amount of capital available for higher risk/higher return projects has rapidly diminished since the Great Recession. The restrictive covenants governing the television industry today serve to exacerbate this problem.

The incredible advances in information technology over the last two decades have made it less costly than ever before to create new content. Unfortunately, the oligopolistic structure of the industry, as enforced by MFNs, makes such creation almost impossible by curtailing competitive distribution. As a result, consumers endure increased prices and diminished content diversity.

Readings

- "Assessing the Effects of Most-Favored Nation Clauses," by Martha Samuelson, Nikita Piankov, and Brian Ellman. Analysis Group working paper, March 28, 2012.

- "How Parallel Most-Favored Nation Clauses in the Television Industry Exclude Competitors and Stifle Innovation," by Bill Toth. Columbia Science & Technology Law Review 15(1): 94–234 (Fall 2013).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.