In July 2015, the Obama administration released a first-of-its-kind report from any White House: a study on occupational licensing. The report gained significant attention because of the novelty of its subject for a White House report, but also for its rather skeptical view of licensing. Mary Kissel, for example, on her July 29, 2015, WSJ Live Opinion Journal program, said incredulously: “Stop the presses. The White House released a report yesterday that says a certain type of regulation kills jobs. The Obama White House said this?”

For many years, the Institute for Justice, the Cato Institute, state policy think tanks, and others have worked to reform licensing laws that amount to little more than a government permission slip to work. But in recent years, the issue finally caught fire among Republican and Democrat policymakers, culminating in the White House report. After reviewing the costs and benefits of licensing—with the former far outweighing the latter—the report offered a series of recommendations for how states should reform their occupational licensing policies and policymaking. The most significant of those recommendations, and likely the most realistic to implement, is a menu of regulatory options that are less onerous than licensing, including “certification (whether private or government-administered), registration, bonding and insurance, and inspection, among others.”

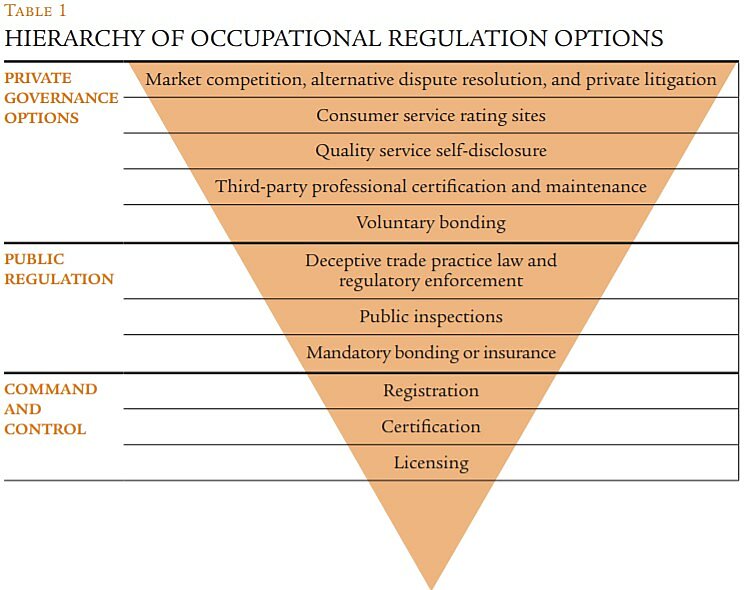

As described in greater detail below, the value and utility of such a menu is that it provides legislators a range of regulatory options between either no licensing or full licensing. This article builds upon that idea by including several private governance options that can realize the public benefits intended by regulation without imposing costs that come with full licensure or other forms of restrictive regulation. Our discussion begins with a presentation of the menu—or hierarchy—of regulatory options as it has been presented in recent years, and then considers additional, minimally restrictive options.

McGrath’s Hierarchy

First conceived by the Institute for Justice’s legislative counsel, Lee McGrath, the hierarchy of regulatory options was designed to compel legislators and industry representatives to consider occupational regulation beyond the above-mentioned license/no license binary thinking that for years has plagued policymaking. Such thinking has all too often seen policymakers swayed by the arguments of licensure proponents, who typically assert both that fencing out “unqualified” practitioners is necessary to protect public health and safety, and that licensing promotes higher levels of service quality.

As the White House report makes clear, however, evidence supporting safety and quality of service assertions is quite sparse, while evidence to the contrary abounds. Moreover, anyone who has witnessed committee hearings on licensing legislation has seen firsthand how little evidence is actually presented or considered and what a one-sided, pro-licensing affair they tend to be. Nevertheless, faced with a decision between no licensing and full licensure, legislators tend to choose the latter in the hope of protecting against the possibility—no matter how remote or unsubstantiated—that someone will be harmed by unlicensed practice. In other words, in a binary world of licensing regulation, better to make a Type I (false positive) error than a Type II (false negative) error.

Enter McGrath and the hierarchy of occupational regulation. Based on years of working with legislators, he recognizes two facts: First, legislators feel compelled to act. They are not, after all, elected on a promise to do nothing. Second and relatedly, legislators will continue to opt for licensure unless given a more attractive alternative than simple inaction. Most occupations, of course, operate just fine with no government intervention, but from time to time a case may be made for some form of regulation. With only two options, a license will likely be created, even if the cost of the intervention outweighs the benefit to public safety.

In response to those options, McGrath created the hierarchy of regulatory options outlined below. In addition to the two options as before—regulation by markets (at the top of the hierarchy) and licensure (at the bottom)—the menu includes a series of options that are increasingly restrictive from top to bottom. In order from least restrictive to most restrictive, these are:

- Market competition/no government regulation. This option should be the default starting place for any consideration of regulation. If and only if empirical evidence indicates a need for government intervention should legislators move to the next option.

- Private civil action in court to remedy consumer harm. Should legislators not be satisfied that markets alone are sufficient to protect consumers, private rights of action are a “light” but effective regulatory option. Allowing for litigation after injuries, even in small-claims courts, gives consumers a means to seek compensation (including court and attorneys’ fees if their claims are successful) and compel providers to adopt standards of quality to avoid litigation or loss of reputation.

- Deceptive trade practice acts. Legislators should look first to existing regulations on business processes, not individuals. These include deceptive trade practice acts that empower state attorneys general to prosecute fraud. Only if there is an identifiable market failure should policymakers move to the next level of regulation.

- Inspections. This level of regulation is already used in some contexts. It could be applied more broadly to other occupations as a means of consumer protection without full licensure. For example, municipalities across America use inspection regimes (which involve a current “permit” allowing commercial operation) to ensure the cleanliness of restaurants—an option deemed sufficient to protect consumers—over the more restrictive option of licensing food preparers, wait-staff, and dishwashers.

- Bonding or insurance. Some occupations carry more risks than others. Although risks are often used to justify licensure, mandatory bonding or insurance—which essentially outsources management of risks to bonding and insurance companies—is a less invasive way to protect consumers and others. For example, the state interest in regulating tree trimmers—as California does—is in ensuring that service providers can pay for the repair to a home or other structure in the event of damage. Such interest can be met instead through bonding and insurance requirements that protect consumers from harm, while allowing for basically free exercise of occupational practice.

- Registration. The option of registration requires providers to notify the government of their name, address, and a description of their services, but does not mandate personal credentials. Registration is often used in combination with a private civil action because it often includes a requirement that providers indicate where and how they can be reached by a process server should litigation be initiated.

- Certification. Certification restricts the use of a title. Under certification, anyone can work in an occupation, but only those who meet the state’s qualifications can use a designated title, such as certified interior designer, certified financial planner, or certified mechanic. Although the voluntary nature of this designation seems contrary to the definition of regulation, it is, in fact, a form of regulation. Certification sends a signal to potential customers and employers that practitioners meet the requirements of their certifying boards and organizations. Certification is less restrictive than occupational licensing, presents few costs in terms of increased unemployment and consumer prices, and provides information that levels the playing field with providers without setting up barriers to entry that limit opportunity and lead to higher prices.

- Licensure. Finally, licensure is the most restrictive form of occupational regulation. The underlying law is often referred to as a “practice act” because it limits the practice of an occupation only to those who meet the personal credentials established by the state and remain in good standing. To the extent that licensure is considered, the need for the creation of new licenses or the continuation of existing ones should be established through careful study in which empirical evidence—not mere anecdote—is presented.

Ideally, policymakers would use this hierarchy to produce regulations that are proportionate to demonstrable need. The process for doing so would identify the problem before the solution, quantify the risks, seek solutions that get as close to the problem as possible, focus on the outcome (with a specific focus on prioritizing public safety), use regulation only when necessary, keep things simple, and check for unintended consequences.

The elegance, utility, and appeal of McGrath’s hierarchy is evident not only by its inclusion in the White House report, but also in the responses of legislators who have seen it as part of presentations he and others have given to state legislators on behalf of regulatory reform. What we propose (with McGrath’s blessing) is not a wholesale change to his hierarchy, but an addition of even more actionable options, specifically near the top, to give lawmakers a greater number of alternatives that require either no direct government intervention or an exceptionally small role for government.

A Dialectic Approach to Occupational Regulation

Our proposed additions are rooted in an innovative public policy approach developed by Edward Peter Stringham in his recent book, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life (Oxford University Press, 2015; see review, Winter 2015–2016). Stringham, the Davis Professor of Economic Organization and Innovation at Trinity College (Connecticut), outlines the use of a variety of private ordering mechanisms, including reputation, assurance, and bonding, all useful for consumers seeking to mitigate fraud in their commercial transactions. This “private governance” approach to commercial regulation (and social ordering) is offered in contrast to “legal centralism,” which is government as the primary arbiter of social rules and enforcement efforts. Legal centralism assumes that markets do not function effectively without the strong, efficacious involvement of government in commercial transactions.

Stringham organizes his mechanism by using a regulatory dialectic approach that effectively complements McGrath’s original hierarchy of occupational regulation. Stringham’s approach begins by asking the following questions (adapted to the “problem” at hand, i.e., occupational regulation):

- Do government regulators have the knowledge and ability to solve the occupational oversight problem in a low-cost way?

- Do government regulators have proper incentive to solve the occupational oversight problem?

While the legal centralist assumes that the answer to both questions is “yes,” the private governance advocate does not. And if the answer to either or both of the questions is “no,” then Stringham would argue that consumer needs remain unmet and a third question should be asked:

- Will the private sector have the ability, knowledge, and incentives to solve the occupational oversight needs of consumers?

If there is an affirmative answer to the third question, then Stringham would recommend the consideration of innovative, private ordering efforts to solve the occupational oversight needs of consumers.

It is important to note one substantive difference between Stringham’s dialectic and McGrath’s hierarchy: Stringham begins his analysis of governance options with the capacity and resources of government and proceeds to private governance only in the event of government shortcomings. McGrath’s hierarchy begins with market competition/private governance and shifts to government intervention only when necessary. In practice, both approaches will typically end up at a similar place, but McGrath’s approach has the advantage of starting from an assumed position of freedom rather than one of government paternalism. As such, the power of inertia favors freedom rather than paternalism.

What we borrow from Stringham is his dialectic approach, which illustrates how additional private governance options can be added to McGrath’s hierarchy. Considering Stringham’s first two questions above, the answer to both is “no” as applied to occupational licensing. As the White House report detailed, a government-mandated license comes with significant costs, such as lost jobs, higher consumer prices, lower mobility, and the growth of government and its trailing costs. Meanwhile, the incentives of government regulators in occupational licensing are perverse. Regulators tend to be dominated by the industry being licensed and have financial incentives to exclude new entrants.

As for the third question, rarely has the answer been so clearly “yes”; hence the enhancements we propose below.

Expanding Private Governance Options

We argue that actively engaging market-based mechanisms—otherwise known as “regulation through markets”—should always precede government regulation as the correct sequence in occupational oversight. Government regulation has been shown to stifle innovation and entrepreneurship, thus reducing competition. In contrast, empirical studies of deregulated, competitive industries show that innovation creates greater deregulated price reductions, while market-based incentives lower costs, improve quality, and develop new products and services.

In an expanded version of the original hierarchy (ranging from least to most intrusive government intervention), we recognize opportunities that the market has recently made available, especially through the widespread availability of the internet and its interactive capabilities between service vendors and consumers. Our “Hierarchy of Occupational Regulation Options,” shown in Table 1, significantly enhances the upper portion of McGrath’s hierarchy, identifying and describing several “private governance” options that consumers can use to evaluate the performance of individuals in an array of occupations and regulate the behaviors of goods and services providers.

The options in the middle of our hierarchy represent “public regulation.” They are enforceable only when an individual’s conduct is contrary to established rules and regulations. The lower portion of the hierarchy also represents “public regulation” options, but they are command-and-control in nature, requiring individuals to be formally acknowledged (under varying degrees of oversight requirements) by a state governmental authority to practice an occupation.

Our additions to the private governance section include the following:

- Market forces, alternative dispute resolution, and private litigation. Alternative dispute resolution, which includes mediation and arbitration, has gained widespread acceptance among consumers, business professionals, and the legal community in recent years. Many courts will require this avenue be utilized before formal litigation can proceed. In addition, the financial threshold for many small claims courts has risen appreciably for consumers. These new options provide a low-cost alternative to formal private litigation for both consumers and occupational practitioners.

- Consumer service ratings sites. Third-party consumer organizations such as the Better Business Bureau, Good Housekeeping, and the Consumers Union have provided consumers with information on the quality of occupational practitioners for decades. More recently, the internet has offered consumers greater access to those groups’ information and spawned new sources such as Angie’s List, a fee-based service for contractors (and now other services). New third-party information sources are appearing online all the time, such as HomeAdvisor.com, Houzz.com, and Porch.com for residential services contracting, and Yelp and Urban Spoon for restaurants and other merchants.

- Quality service self-disclosure. This works in conjunction with the preceding option. With virtually all occupational practitioners having online websites, the ability to actively link to third-party evaluation sites will provide consumers with an important competitive “signal” that the practitioner is open to disclosure regarding the quality of his or her service. This is a market-based incentive that helps consumers differentiate highly competent, price-competitive occupational practitioners from mediocre ones.

- Third-party professional certification and maintenance. The National Commission for Certifying Agencies was created by the Institute for Credentialing Excellence in 1987. It has accredited approximately 300 professional and occupational programs from more than 120 organizations over the past three decades. These occupational certification programs cover, for example, nurses, automotive occupations, respiratory therapists, counselors, emergency technicians, and crane operators, to name just a few. Such occupational certifications, to be maintained, often require continuing education units. Most importantly, many organizations make such certifications a requirement for employment.

- Voluntary bonding. Voluntary bonding—a guarantee of job performance and customer protection against losses from theft or damage by employees—is most common among general contractors, temporary personnel agencies, janitorial companies, and companies having government contracts. For the knowledgeable consumer, voluntary bonding makes the business more desirable, and potential customers increasingly demand it.

As this list shows, the market has responded with a myriad of innovative and still-developing alternatives to public regulation. Rather than continuing to engage in the binary thinking on occupational regulation that has so often led to unnecessarily restrictive licensure, legislators and industry representatives would do far better to clearly recognize and evaluate the many less onerous, less intrusive market-based alternatives that can effectively work to protect consumers and ensure service quality.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.