In 1970, French sociologist Michel Crozier published a book titled La société bloquée, soon translated into English as The Stalled Society. French society, he argued, was stalled because of a centralized and hierarchical state bureaucracy that has remained in power since the Ancient Regime, as Tocqueville had already diagnosed in The Ancient Regime and the Revolution (1856). Today, the trade unions, which represent less than 8% of French workers—about 5% in the private sector—constitute another powerful interest group. The powers of the bureaucracy and the unions mobilize public opinion and obstruct change.

We were recently reminded of the stalled society by the (sometimes violent) street demonstrations and refinery blockades that opposed a modest reform of France’s inflexible labor laws. In July, the government partly yielded to the protesters and toned down the reform, which mainly decentralizes the collective bargaining of working hours.

In 1964, a young Ronald Reagan, speaking on behalf of Barry Goldwater, said that France had “come to the end of the road,” referring to the cost of the French welfare state. Similar pronouncements have been made about the French economy in the years since. Yet, somehow France never seems to run out of road. If it is such an overregulated société bloquée laboring under a dirigiste state, why hasn’t France’s economy crashed?

A Dirigiste State

The French state casts a large shadow over economic freedom. In the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, arranged from the freest to the least free, France ranks 75th out of 178 countries, which makes it a “moderately free” country according to the report. The United States ranks 11th, having fallen from the “free” to the “mostly free” category in 2010. France’s ranking is similar in the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World index: among 157 countries, France is 70th and the United States is 16th. In the latter index, France’s deficiencies are attributed to the size of government and regulation (mainly labor market regulation).

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, an association of mostly wealthy countries, publishes an index of Product Market Regulation, which tries to measure state control of businesses, barriers to entrepreneurship, and obstacles to trade and investment. According to 2008 data, the last year they are available for all 34 OECD members, the United States ranks as the second-least regulated country, after the Netherlands. France ranks 17th, in the middle of the pack.

The OECD’s indexes of Employment Protection Legislation point in the same direction. In the regulation of dismissals of permanent employees as well as in the regulation of temporary employment (which is necessary if dismissal of permanent employment is regulated), the United States is among the least regulated countries, while France is close to the bottom. Most mainstream economists consider the flexibility of labor markets especially important for economic efficiency, economic growth, and the standard of living.

Public expenditures amount to 57% of French gross domestic product, the fourth-highest percentage in the OECD, after Greece, Slovenia, and Finland. This compares to 45% for the OECD unweighted average and 39% for the United States. (Data are for 2013, the latest year for which the OECD provides complete comparative data.) The ratio of public debt to GDP is higher in France than in the United States.

French public opinion is broadly ignorant of, and opposed to, economic freedom. Jean-Pierre Dormois, a French economic historian, writes that “economic illiteracy and the endurance of unorthodox doctrines in academic teaching and the media contribute to keeping radical utopias on the political agenda.” A hopeless case, isn’t it?

A Rich Country

Despite all that, France is a rich country and the French economy is not doing badly. Ranked by GDP, France is the second-largest economy in the European Union, after Germany and just before the United Kingdom. France’s demise has not yet happened. Consider the following facts.

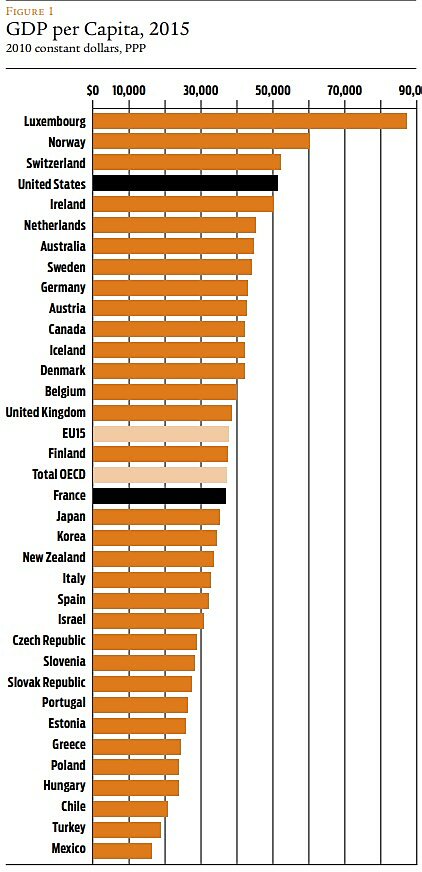

The best (or least bad) criterion to evaluate an economy is the standard of living, and the best (or least bad) way to measure the standard of living is GDP per capita. If one compares different territories or countries, GDP per capita must be converted to a common currency (say, dollars) and expressed in real terms. The rate of conversion used, called purchasing power parity (PPP), is the currency exchange rate corrected by the relative price level in the two countries.

Figure 1 presents GDP per capita data for the 34 OECD countries. For our purpose, we can ignore two special cases: Luxembourg, a tiny country with an oversized financial sector, and Norway, where 15% of GDP comes from oil. Of the other 32 countries, Switzerland and the United States are at the top, with GDP per capita of $52,000 and $51,000 respectively. Over the core 15 European Union countries as well as the whole OECD, the average is about $37,000. France lies very close to this (weighted) average, not far behind the United Kingdom.

There is much evidence that economic freedom promotes prosperity. For example, James Gwartney, Robert Lawson, and Joshua Hall calculate, on the basis of the Fraser Institute’s index, that the average annual rate of GDP growth of the least economically free countries (the bottom quartile) is 1.17% per year, while the freest (the top quartile) achieve 3.27% per year. Over 50 years, this difference translates to a GDP multiplied by 5 in the fast-growing countries and by less than 2 in the slow-growing ones. Taking population growth into account, the difference in the standard of living may be even more pronounced.

The United States, despite its recent fall in terms of economic freedom, maintains a higher standard of living than we might expect on that account. At a lower level of economic freedom, France appears to be doing relatively well. In this sense, both America and France are outliers.

Labor productivity has been suggested as an explanation for France’s relatively good performance. A simple measure of labor productivity, GDP divided by the number of workers or by the number of hours worked, shows a very productive economy. “In 2013, output per worker in France was 13 percent higher than in the UK,” noted the Financial Times (March 19, 2015). “But because Britons work longer hours than the French, on a comparison of GDP per hour, the difference umps to a whopping 27 percent.” Or, as The Economist (July 16, 2016) put it, with 15% fewer workers who work shorter hours, the French produce roughly as much as the Brits. Another indication of high labor productivity in France: GDP per hour worked was slightly above American labor productivity from the early 1990s to the early 2000s.

The Statist Hypothesis

How is the French economy surviving and even thriving? How can we explain this paradox? I think there are three possible answers.

The first is that the French are prosperous precisely because of government dirigisme. Call this the statist hypothesis. I am highly skeptical of this idea. It has been shown empirically that heavy regulation has a negative effect on the standard of living. (See “A Slow-Motion Collapse,” Winter 2014–2015.) Even economists on the left of the political spectrum tend to reject the statist hypothesis. For example, three French economists, Gilbert Cette, Jimmy Lopez, and Jacques Mairesse, calculate that adopting the lightest regulatory practices for product and labor markets in France would ultimately increase multifactor productivity (and thus GDP) by nearly 6%. (Multifactor productivity is another measure of productivity; I will discuss it below.)

To the extent that good governance favors economic efficiency, as a large number of economists believe, France has good governance. Generally speaking, the French government is neither corrupt nor derelict. But there is too much of it.

A Matter of Degree

A second, more promising, explanation for France’s seeming economic health is that the French economy and society are not as nationalized and regulated as people commonly believe. There are many indications that between France and other rich countries—including the United States—the difference in government intervention is only a matter of degree.

Even when regulations seem more stringent in France, their enforcement may be more relax. One reason is the absence of American-style, powerful, semi-independent, central agencies with their own law enforcement arms and even militarized units. In France, it’s the ordinary police that enforce the laws. The French are also more used to, and probably more efficient at, breaking regulations than Americans are. One indication is the size of the underground economy. A standard estimate by Friedrich Schneider, an expert on the subject, is that the underground economy equals 15% of official GDP in France, compared to 9% in the United States. The underground economy is the ultimate way to avoid regulation.

Not all industries are more regulated in France than in America. The OECD’s Services Trade Restrictiveness index shows France as less regulated than the United States in commercial banking, insurance, broadcasting, and many modes of transport. Even the labor market is less regulated in France with regard to many trades and professions. In the United States, nearly 30% of jobs require a license.

The typical American thinks that France is more regulated and dirigiste than it is, while the typical Frenchman believes that America is less regulated and dirigiste than in reality.

Another example: the so-called 35-hour French work week, legislated in 2000, allows for exceptions, which have gradually expanded over time. What the law now means is that after 35 hours, overtime must be paid. Moreover, argues Steve Priddy of the London School of Business and Finance and the Grenoble School of Economics, contracted hours may not correctly reflect the actual time worked. (Incidentally, this may imply that the number of hours used to calculate hourly productivity is understated, thereby exaggerating French labor productivity.)

Entrepreneurial paradise? / Fabrice Cavaretta, a professor of entrepreneurship and leadership at a major Paris business school, claims that (according to the title of his recent book) Oui! La France est un paradis pour les entrepreneneurs (Yes! France Is a Paradise for Entrepreneurs, Plon, 2016). “Putting an end to ‘French Bashing,’ ” boasts the book cover.

According to Cavaretta, real entrepreneurs can easily succeed in France. Many factors help: France’s global brand reputation (in fashion, luxury goods, food, tourism, culture), good public educational and social infrastructures, subsidies for entrepreneurs, and generous social programs (such as unemployment insurance) in case of failure. With its vast military procurement (just like the United States, notes Cavaretta) and its national champions (Total, EDF, Bolloré, etc.), the French state is, and has been, a plus for real entrepreneurs. Cavaretta suggests that industrial policy is a more self-conscious tradition in France, while it is hidden in the American military-industrial complex.

French regulation, he argues, is really no more constraining than American lawyers are. In common law countries, he writes and underlines, “nothing can be done without lawyers.” In France, you may have to talk to “the Administration”—the state bureaucrats—but they are not too difficult to talk to. As for trade unions, they are not a piece of cake in the United States either. The World Bank’s Starting a Business index, he points out, indicates that it is easier to start a business in France (which ranks 32nd among 189 countries in the 2016 report) than in the United States (49th). Anyway, a real entrepreneur will not be discouraged by taxes or labor costs that are a bit higher than elsewhere.

Although “dirigisme” is a French word, France also has a long tradition of relatively free markets. In the late 19th century, according to estimates compiled by Vito Tanzi and Ludger Schuknecht, the ratio of public expenditures to GDP was 13% in France. That exceeded the 7% of the United States, the 9% of the UK, and the 11% average for all major countries, but the differences is not overly dramatic. In 1960, the relative differences were even smaller: the OECD estimated the ratios to be 35% in France, 27% in the United States, 32% in the UK, and 31% in the OECD overall excluding the United States—quite small differences, especially in contrast to today’s ratios.

It is perhaps not surprising that, with this capital of relative economic freedom, the French economy grew rapidly after World War II. The gap between French and American GDP per capita was reduced from 47% (that is, GDP per capita in France was 47% lower than in America) in 1950 to only 17% in 1974.

Misplaced Optimism

This rosy picture of the French economy may be overly optimistic. The third way to solve the French paradox lies in a different direction: the observation that the French economy is not doing that well after all. Look deeper and there may be no paradox to explain.

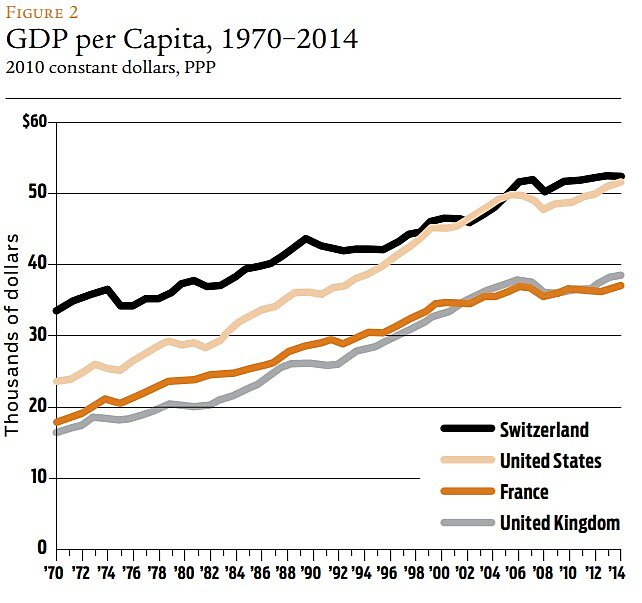

Figure 2 shows GDP per capita over time in Switzerland, the United States, the UK, and France. (The figure uses the same OECD data as Figure 1: real 2010 dollars corrected with PPPs.) The United States is doing well compared to everybody, including Switzerland. France has fared well compared to the UK, but its growth has slowed since the beginning of this century. More generally, the growth gap started turning against France in the mid-1990s (in a context of reduced growth nearly everywhere).

Cette and his colleagues Antonin Bergeaud and Rémy Lecat analyzed this slowdown by breaking down the growth of GDP per capita into what can be attributed to increasing capital (machines and equipment), increasing labor (number of workers and hours worked), and multifactor productivity. Multifactor productivity (also called “total factor productivity”) incorporates all influences other than labor and capital in the growth of GDP; it includes technical progress, entrepreneurship, as well as social, political, and economic institutions. Since the work of Nobel prizewinning economist Robert Solow in the 1950s, we know that multifactor productivity explains a large part of GDP growth.

The standard growth accounting method used by Bergeaud, Cette, and Lecat produces estimates of the differential effect of labor, capital, and residual factors. It is a better method for measuring productivity. Simply dividing GDP by the number of workers or their hours worked ignores that labor productivity depends partly on capital, technology, and the surrounding social, political, and economic institutions. Labor productivity measured by GDP per hour worked—which, as we saw above, suggests that French productivity is high—is in fact a poor measure of productivity.

What does the growth accounting method tell us about the last four decades of slowing French growth? Bergeaud, Cette, and Lecat distinguish two distinct sub-periods: 1974–1995, and 1995–2012. (Their data set ends in 2012.) Between 1974 and 1995, slower economic growth in France is explained by a reduction in the contribution of labor inputs. The analysis suggests that this reduction is due to both work disincentives created by social policies (unemployment insurance and lower retirement age, for example) and regulatory reductions in working time (the 39-hour work week among others). In many other European countries, similar factors contributed to a slowdown or even a reversal of what had been a 30-year ongoing reduction of the gap with the American standard of living. In France, the catch-up with America screeched to a halt.

Since the mid-1990s, France and many other European countries (but not the UK) have suffered a widening gap with the U.S. standard of living. During that period, the culprit was the slowdown of multifactor productivity growth, especially noticeable in France. According to another paper by Cette and Lopez, the underlying causes were a slower diffusion of the new information technologies, structural rigidities in labor and product markets, and a less educated working population. From 1995 to 2012, French GDP per capita grew at a meager 1% per year.

The Consequences of Dirigisme

Besides regulation and market inflexibility, the large amount of redistribution and government expenditures must have contributed to the French slowdown. As indicated by Figure 2, the UK’s GDP per capita appears to have now overtaken France’s (although this may be reversed by Brexit).

French labor laws are more constraining than the rosy view presented above. They impose costs on firing and thus, probabilistically, on hiring. Because of the cost of firing employees, firms are incited to resort to short-term labor contracts, a loophole that further regulations have tried to limit. In France, a short-term contract may not extend beyond 24 months. The employed work force has thus acquired a dual structure: on one side, the “insiders”—regular workers protected against dismissal; on the other side, the “outsiders,” who survive on short-term contracts and hop from job to job. Outsiders make up about 15% of the employed, a proportion that climbs over 50% in the 15–24 age category.

Trade unions exert a large influence through collective bargaining. The main trade union, the Confédération générale du travail, has long been associated with the Communist and Socialist parties, and is ideological and politicized. Any firm of more than 49 employees must create a “work council” (comité d’entreprise) chaired by a representative of the owners but composed of trade union representatives and representatives elected directly by the employees. Consultation of the work council is compulsory on many business decisions. Even businesses of 11–49 employees are forced to allow the election of employee representatives.

To appreciate the spirit of the 2,880-page Labor Code, consider that the French government is currently pushing businesses to negotiate with their workers’ representatives a “right to disconnect,” referring to after-hours work-related electronic communications. The Department of Labor, Employment, Occupational Training, and Social Dialogue (why they didn’t add “General Happiness” to the name is a mystery) explains that “the employees of a large firm are not obliged to answer emails outside of office hours.”

The World Bank’s Starting a Business index invoked by Cavaretta is the rosy part of the story. This index does rank France ahead of the United States based on such factors as that it typically takes just five procedures and four days to legally start a business in France, whereas it takes six procedures and 5.6 days in the United States. Is that difference such a big deal? Furthermore, the Starting a Business index is only a sub-index in the more general Doing Business index, which includes such components as Dealing with Construction Permits, Registering Property, Paying Taxes, and Resolving Insolvency. In the overall Doing Business index, the United States climbs to 7th, as compared to France’s 27th. (I am using 2016 data, which shows only inconsequential differences with the 2015 data used by Cavaretta.)

Of course, an index is just an index and should be taken with appropriate grains of salt. But the World Bank’s indexes throw some doubts on the notion of a French entrepreneurial paradise.

The centralized nature of the French state often makes regulation more burdensome in the labor market and other areas. For example, after conventional taxi drivers demonstrated, often violently, against Uber’s non-licensed drivers, the French government imposed a country-wide ban on ride-sharing. The ban (which does not apply to an Uber service with licensed drivers) was confirmed by a Paris court, which found the company guilty of “complicity in the illegal exercise of the taxi profession.” Occupational licensure is not absent from the French labor market.

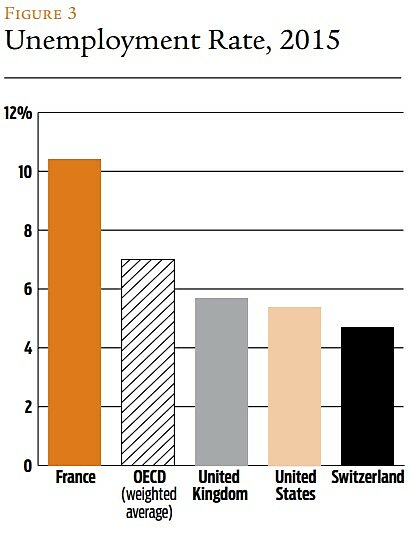

Unemployment / One very visible consequence of all that regulation is unemployment. Figure 3 shows that the French unemployment rate of about 10% is higher than in the whole OECD, and much higher than in the UK, United States, and Switzerland. The French unemployment rate is double the U.S. rate. And in France, 44% of those unemployed have been so for more than a year, much higher than the 31% in the UK and the 19% in the United States.

In the mid-1970s, the French unemployment rate was around 4%, but it has exploded since then. The fact that it is roughly the same as in the European Union does dampen the relative severity of the problem; overregulation and perverse incentives are a problem across the continent.

Youth unemployment is a dramatic problem in France. In 2015, the rate of unemployment of 15–24 year olds was 25%, compared to 14% in the whole OECD zone, 15% in the UK, 12% in the United States, and 9% in Switzerland. Some European countries have a higher youth unemployment rate than France, but they are generally poorer countries like Greece or over-regulated like Italy.

Working is not the purpose of life, of course, and employment is merely a means to earn an income and consume goods and services. But when people who want to earn a living and work at the prevailing wage are unable to find a job, the results are economic inefficiency, loss of personal development, and social problems. The situation is especially tragic for the young, who struggle with integrating into productive society (even if they benefit from the welfare state’s assistance).

Dormois writes, “The hardships encountered in and out of the workplace may explain why the French have become the world’s largest consumers of tranquillisers.” The French regulatory and welfare state has failed in many ways.

French taxpayers pay dearly for their welfare state. Defined as including public expenditures on social protection and health (but not education), the welfare state grabs 57% of public expenditures in France—compared to 50% in the OECD (unweighted average) and 43% in the United States. (Note that the equality of the ratio of welfare-state expenditures to government expenditures and the ratio of public expenditures to GDP in France is a statistical fluke.) Given the ratio of public expenditure to GDP, the proportion of welfare-state expenditures in GDP amounts to 32% in France, 23% in the OECD (unweighted average), and 17% in the United States.

I could give other examples of the cost of the French welfare state. It would be risky to copy the French welfare state in America—or to copy it more.

Matter of concern / The economic situation in France is so dire that recent attempts at reform were made by a Socialist Party government. Many analysts on the left admit that the French economic situation is worrisome, especially on the labor regulation front. In a recent book, Cette and Jacques Barthélémy (the latter a labor law and “social law” expert) argue that current labor laws need urgent reform because they are economically inefficient and don’t even protect all workers—the outsiders and unemployed bearing witness. Cette and Barthélémy’s solutions, however, are mired in collective bargaining and collective choice as opposed to individual economic freedom.

Despite his left leanings, Cavaretta recognizes a major symptom of what Alain Peyrefitte called le mal français (“the French disease”). Peyrefitte, a government minister under Charles de Gaulle in the 1960s, published a book with that title in 1976. (In earlier times, the “French disease” referred to syphilis.) Optimistic about the French paradise, Cavaretta does not use the expression “mal français,” but he recognizes a real symptom of it: an economic and business culture that privileges the producer over the consumer. He does not seem to realize that this culture is a consequence of the primacy of public institutions that he lauds. Nearly four decades ago, French philosopher Raymond Ruyer described the phenomenon brilliantly: “In a market economy, demand is commanding and supply is begging,” he wrote. “In a planned economy, supply is commanding and demand is begging.” The value of entrepreneurs lies in their contribution to satisfying consumer demand. Consumer sovereignty is what matters. These ideas are largely missing in French economic culture.

France, of course, is not really a planned economy, but its government and tradition are more dirigiste than in many other Western countries. In this context, it is wishful thinking to imagine an explosion of entrepreneurship in France.

Thus, a third answer to our original question on the French paradox would be that the end of the road does indeed appear to be drawing closer for France. At the very least, we certainly cannot say that the French economy is thriving.

A Double Answer

I think the answer to our original question probably calls for a mix of the last two explanations.

We saw that apparently stifling regulations are probably not as binding in France as they would be in the United States because of both regulatory arbitrage (circumventing regulations through active exploitation of loopholes) and Gaelic disobedience. More important, the difference between the level of formal regulations in France and America is only a matter of degree and this difference is smaller than generally believed.

Nonetheless, the French economy, while not bankrupt, is not doing well. There is less of a paradox than first meets the eye. Free markets, even when compressed, are resilient, in France as elsewhere, but there can still be a slow-motion collapse if no decisive reforms are successfully undertaken.

This last point applies to other more-or-less free economies, including the United States. We don’t know for sure why the growth in productivity and GDP per capita has slowed in most developed countries since the 1970s—including in the United States, although to a lesser degree than in France. One cause has likely played a not-insignificant role: more regulation and less market flexibility. In the United States over the past six decades, federal regulation has increased seven-fold, adding to pervasive and growing state and local regulation. Public expenditure and public debt have increased, adding to the economic burden.

Among democratic countries during the 20th century, France has pushed democratic dirigisme only a little more consistently than other countries. Perhaps it will turn out to be the canary in the mine.

Should the United States Be More Like France?

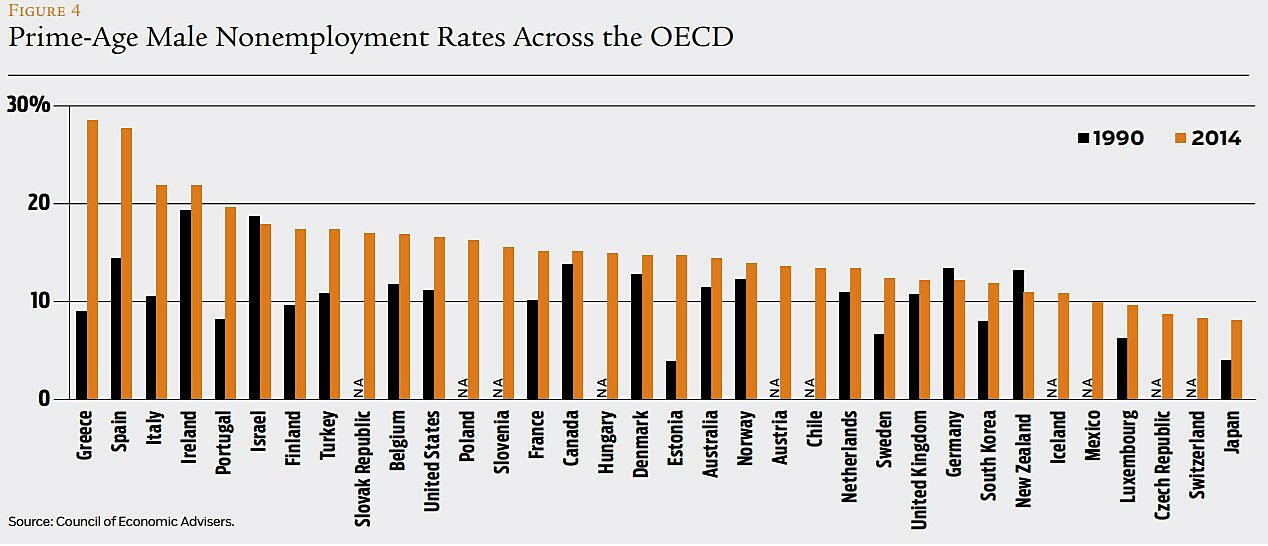

In June, the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), a White House agency, published a report challenging the idea that labor market flexibility is unambiguously desirable. Titled The Long-Term Decline in Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation, the report argues that, despite the flexible labor market in America, the participation rate of men aged 25–54 (prime-age men) in the labor force has been declining for six decades, from 98% in 1954 to 88% today. The New York Times story (June 20, 2016) on the report asked, “Would America have fewer missing workers if it were more like France?” Perhaps more control of the labor market and less flexibility are needed?

The decline of prime-age men’s participation in the labor force—“participation” meaning people who are either working or actively looking for work—has been sharper in the United States than in other advanced economies (which typically have less flexible labor markets), up to the point where the United States now has the third lowest participation rate of prime-age men among OECD countries. The trend is especially grim for men with a high school degree or less, and among black men.

The report argues that the main explanation lies in a reduced demand for prime-age male workers. The reduced demand “could reflect the broader evolution of technology, automation, and globalization.” The report proposes to shift the focus from market flexibility to a host of interventionist government policies.

One problem with the CEA report is that it does not satisfactorily demonstrate that more assisted, less flexible, European-style labor markets could solve the apparent problem of the missing workers. Many European countries with typically heavier government intervention in the labor market show a rate of participation of prime-age males closer to the lower U.S. rate than to the higher French rate. These low-participation countries are Italy, Norway, Finland, Ireland, Denmark, Poland, Belgium, Hungary, and Austria (not to mention Australia and Canada).

There may be a problem with the labor force participation of prime-age males in the United States, but other age groups or demographics are not necessarily affected. For example, U.S. Hispanic prime-age males roughly maintained their participation rate over the past 20 years, as the CEA report documents. If we consider the participation rate for all age groups and both sexes (labor force as a proportion of the population more than 15 years old), it is higher in the United States (62.7%) than in France (56.1%) and the EU in general (58.1%).

Moreover, not much is gained, it would seem, if nonparticipants suddenly started to participate but couldn’t find jobs. A more useful statistic to consider is the ratio of employment to working-age population. Recall that the labor force includes both the employed and the unemployed looking for work. The employment ratio for all working-age men (15–64 years of age) is actually higher in the United States (74.2%) than in France (67.4%).

Regarding prime-age males, here is another way to see this point. Define the nonemployed as the sum of the nonparticipants and the unemployed. The prime-age males’ nonemployment rates are shown in Figure 4, reproduced from the CEA report. We can see that France’s most recent (2014) nonemployment rate (nonparticipation plus unemployment) of prime-age males is not much below the U.S. rate. (The CEA report does not provide the exact numbers.) The reason for the small difference is that unemployment is much lower in the United States, and that compensates in large part for nonparticipation. In the United States, in other words, fewer people participate in the labor force, but more of those who do actually get a job.

The report does admit that “a higher labor force participation rate is not an objective of economic policy in and of itself.” Let’s elaborate. People may want to take more leisure for a number of reasons. External shocks or long-term change may hit particular groups of workers. Besides, why should we suddenly start to worry about a decline in the prime-age males’ participation rate when that decline has been going on for six decades? Yet, the report assumes that it is a problem that requires government solutions over and above abolishing the obstacles created by the government itself.

One standard argument against a low participation rate is that people totally detached from the labor force (as opposed to the unemployed, who are by definition still looking for a job) are unlikely to ever reintegrate into the labor force. But the same is largely true for the long-term unemployed, of which France has many. Having been out of work or out of the labor force often means the same struggle to find a job. In France’s inflexible labor market, the long-term (12 months and over) unemployed represent 44% of the unemployed, compared to 19% in the United States.

Another problem with the CEA report is that it does not explain why wages have not adjusted enough to clear the market (that is, to eliminate unemployment disguised as nonparticipation) following the presumed reduction of demand for the labor of prime-age men. Either the explanation lies in market inflexibilities, in which case we should keep the focus on this problem, or the labor market for prime-age men has effectively cleared, in which case the lower participation rate is explained by a voluntary reduction of the quantity supplied of labor along the existing supply curve (a reduction albeit encouraged by government subsidies such as disability insurance, Medicaid, etc.).

To be fair to the CEA, the report does criticize some barriers created by the government itself. It argues against occupational licensure as a barrier to participation in the labor force. It recommends reducing disincentives to work created by the combination of the tax system and assistance programs. It proposes (prudently and fuzzily) to deal with the scandal of over-criminalization and mass incarceration: 6% to 7% of prime-age males are incarcerated at some point in their lives, making it much more difficult for them to find jobs afterwards. The authors must be congratulated for raising those issues.

Hodgepodge of bad ideas / However, most of the report’s proposals constitute a hodgepodge of policies that are already being pursued by the White House for other reasons. Many of these ideas would add to the sort of labor market overregulation that afflicts France and other European countries. Among the proposals: job creation in public infrastructure; subsidized employment and job search; government support of education and training; access to paid family leave, paid sick days, child care, and early learning programs; a higher minimum wage; wage insurance; and more collective bargaining.

Therein lies the most serious flaw of this report. New interventions won’t correct the deleterious effects of past ones.

A good example of a recycled and counterproductive proposal is the idea of increasing the minimum wage. Such a measure would create more unemployment among blacks and less educated male workers, who are the most likely to drop out of the labor force. (See “From Minimum Wage to Maximum Politics,” Summer 2014.) Contemplating the mirage of a job with a higher minimum wage, these people may switch from being nonparticipants to being long-term unemployed. How that would improve people’s lives is unclear.

Increasing government subsidies to “support” the labor market—with measures such as subsidized child care—would increase public expenditures closer to European levels. If such measures were economically efficient, the French standard of living would not be 28% lower than America’s. Moreover, how would subsidized child care affect the participation of prime-age males? The report itself shows that those who have dropped out of the labor force are mostly nonparents. But if these sorts of policies were adopted, the ruling intelligentsia would feel good and get more power.

To the New York Times’s question—“Would America have fewer missing workers if it were more like France?”—we can quite confidently answer no.

Readings

- Economic Freedom of the World: 2015 Annual Report, by James Gwartney, Robert Lawson, and Joshua Hall. Fraser Institute, 2015.

- Éloge de la société de consummation (In Defense of the Consumer Society), by Raymond Ruyer. Calmann-Lévy, 1969.

- “Le produit intérieur brut par habitant sur longue période en France et dans les pays avancés: le rôle de la productivité et de l’emploi” (“Gross Domestic Product per Capita over the Long Term in France and in Advanced Countries: The Role of Productivity and Employment”), by Antonin Bergeaud, Gilbert Cette, and Rémy Lecat. Économie et Statistique, Vol. 474 (2014).

- Public Spending in the 20th Century, by Vito Tanzi and Ludger Schuknecht. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Réformer le droit du travail (For a Reform of Labor Law), by Jacques Barthélémy and Gilbert Cette. Odile Jacob, 2015.

- The French Economy in the Twentieth Century, by Jean-Pierre Dormois. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.