There is ample evidence and literature that outgoing administrations tend to increase regulatory output after Election Day, up until the next president takes office. This “midnight regulation” is a rational way for a departing president to cement as many domestic priorities as possible. But it arguably is also an attack on the will of the people because it is most pronounced when there is a party change in the White House, indicating a popular desire for policy change.

To address midnight regulating, Congress adopted the “carryover” provision of the Congressional Review Act (CRA). The provision allows an incoming Congress to overturn a rule enacted in the waning weeks of the outgoing presidency. But is this power effective? Or do presidents act to finalize regulations well before Election Day, beyond the provision’s reach? In other words, is there a “twilight” before the midnight regulation period?

Carryover provision / The CRA allows a sitting Congress to review final rules for 60 legislative days after the rule has been issued. In that period, Congress can pass legislation, subject to presidential veto, blocking the rule. The carryover provision extends this power to an incoming Congress for a rule issued during the last 60 legislative days before adjournment of the previous Congress. In essence, this provision gives the new Congress 75 legislative days to review and block the new rule.

But Congress has only used its CRA power once, despite all of the late-term presidential regulation. This raises the question, do outgoing presidents avoid this review by finalizing controversial regulations before the final 60 legislative days of a congressional term?

Prima facie, presidents would face some difficulty with employing this strategy. First, the exact day the carryover provision becomes effective cannot be known until Congress adjourns its session. Any president wishing to finalize a flurry of rules would have only a vague idea ahead of time of the carryover provision’s start date and it would be largely dependent on another branch of government. For instance, the carryover date for 2016 was initially estimated to be May 17th, a figure later confirmed by the Congressional Research Service. But Congress stayed in session a few extra days (relative to its initial calendar), pushing the carryover day closer to May 23rd. So if there is a party change in the White House following this November’s election, the (currently) opposition-controlled House and Senate could decide to take off November and December, in which case the carryover date would be closer to May 1. This might be too much uncertainty for a president to plan a regulatory agenda around the CRA.

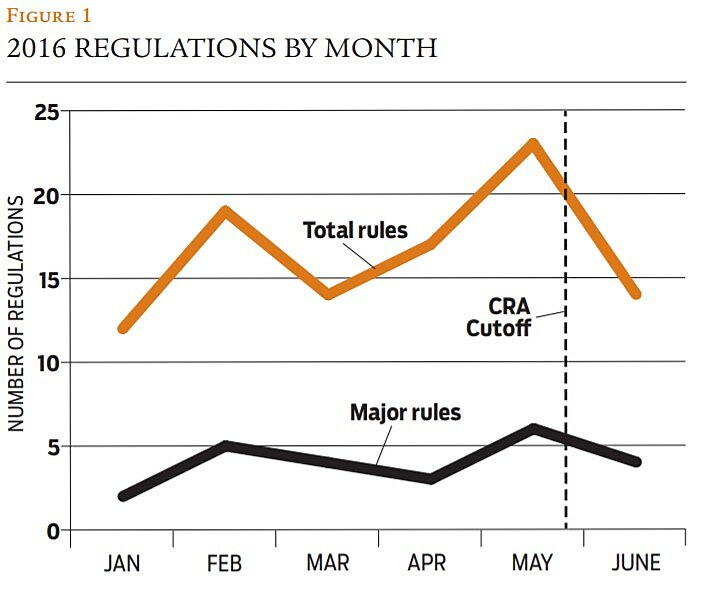

A rush? / To detect a twilight phenomenon, we have only a limited amount of data to examine. There is some evidence that the administration and regulators (the CRA applies to independent agency actions as well) may be twilight-regulating this year. Figure 1 displays the rate of total and major rulemakings so far this year, with a line denoting a probable CRA carryover date.

The figure is hardly a slam dunk in favor of the hypothesis that presidents act to finalize rules before the CRA takes effect, but there is a noticeable spike in May for both total and major rules. Here are a few especially controversial rules released from the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) the month before the CRA cutoff:

- E‑cigarette regulation

- Methane standards for oil and natural gas

- Overtime expansion

- Renewable fuels standard

In May of 2016, OIRA approved 14 significant rulemakings, which was more than any other May in a presidential election year since 1996. Regulators also estimated the rules would impose $22 billion in costs, compared to just $2.8 billion in costs for the rules approved in May of 2015. These data are suggestive, though it should be noted that they don’t prove that the carryover provision of the CRA rushed certain decisions by the Obama White House.

Another source of data to test this hypothesis is the Unified Agenda, which shows various rulemakings’ progress through the regulatory process. Were there rules issued before their target publication dates (a rarity in the regulatory world) in order to beat the carryover deadline? For example, the administration said it was still analyzing comments from its controversial fiduciary rule as late as December 2015. However, OIRA started review of the proposed rule in January and the rule was final by April, ahead of schedule and well before the carryover date. Likewise, the Environmental Protection Agency’s final fracking standards for oil and natural gas weren’t expected to be final before June 2016, but OIRA concluded review in early May. Finally, the overtime rule was expected to be final in July of 2016, likely past the CRA date. However, OIRA concluded review on May 17 and it was officially published shortly thereafter. These instances are suggestive, though they do not yield statistically significant findings.

We conducted a much larger review of every rulemaking from 1996 (when the CRA was adopted) to the present. We used the CRA deadline as computed by the Congressional Research Service, and then examined rulemaking activity (both major and overall rules) the month before that date. The control was non-presidential election years when a CRA date is still computable.

During presidential election years, OIRA approved an average of 4.6 major rules (including eight in 2016) in the month before the CRA carryover date took effect. In non-presidential election years, this figure was 4.1. Looking at all rulemakings, not just major rules, regulators approved 21.5 final rulemakings in the month before the carryover date during presidential election years. During off-year elections, OIRA released just 17.2 regulations the month before the carryover date.

A t-test finds that these differences are not statistically significant. However, this is a small sample size: there is only a comparison between average activity in six presidential election years since 1996 and 15 non-presidential election years. The higher presidential election year averages and a graphical look at the timeline of regulations suggest that administrations are cognizant of the CRA cutoff date.

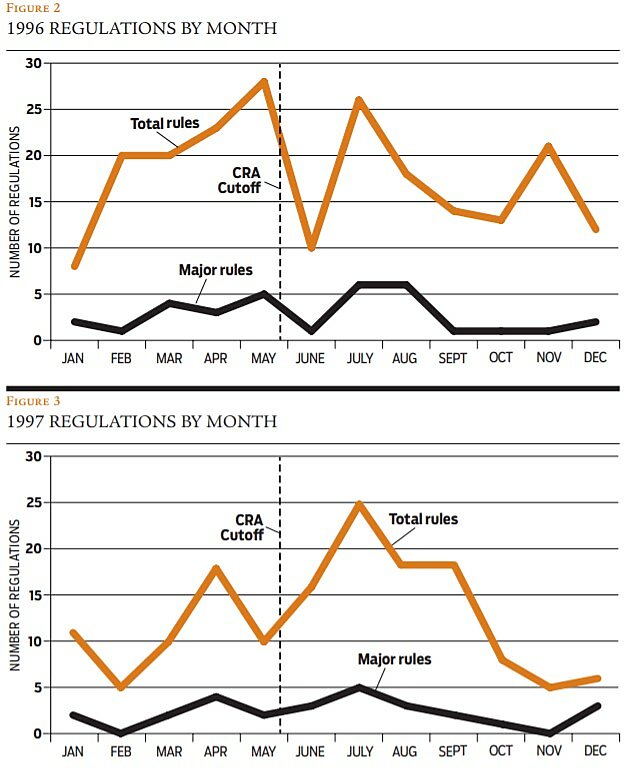

For example, Figure 2 displays major and overall regulatory activity from OIRA in 1996 and 1997. As with 2016, there was a noticeable spike in regulatory activity the month before the CRA took effect in 1996, with 28 regulations. Compare that to 1997, which is shown in Figure 3. That was a non-presidential election year, when OIRA approved just 13 rulemakings and there was actually a decrease in activity before the hypothetical CRA carryover date took effect.

Conclusion / At first blush, the notion that presidents act to cement their regulatory priorities before the next Congress has a chance to repeal them sounds like a truism, rather than a hypothesis in need of empirical testing. There is some suggestive evidence indicating small spikes in regulation before the CRA carryover provision becomes effective, but the difference between off–election years is not statistically significant. This could be due to the small sample size or simply because the speculative nature of the carryover date does not motivate presidents to rush major regulation. From what we do know, presidents can always wait until the midnight period to implement major rules.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.