Assuring that affordable, high-quality drug therapies are available in poor countries is a priority for policymakers, scholars, and advocacy groups around the world. However, there is little agreement over how to achieve that goal. Some see international arbitrage as a solution. Its proponents would allow firms to buy patented, trademarked, or copyrighted goods in countries where prices are low (perhaps because of local price controls or lower wholesale prices set by manufacturers) and re-sell them in higher-price countries without the permission of the owner of the intellectual property rights attached to the goods. They argue, among other things, that such behavior enhances competition in international markets and thus improves welfare, especially for lower-income consumers.

This view alarms many scholars, especially when such "parallel trade" (meaning the goods in question sometimes travel a parallel route out of the manufacturing country and then back again) involves pharmaceuticals. They note that developing and obtaining regulatory approval for new drugs frequently involve enormous fixed costs and low marginal costs of production. Recovering the fixed costs while maximizing the gains from exchange commonly requires not a uniform price across markets and countries but, rather, adept price discrimination. These scholars claim that "Ramsey pricing"—higher prices in affluent countries where demand for pharmaceuticals is inelastic, and much lower prices in poorer countries where demand is more elastic—would maximize welfare and be more likely to recover fixed and marginal costs. They warn that allowing parallel trade would cause prices to fall toward marginal costs everywhere, disrupting the Ramsey pricing scheme and reducing research and development investment and innovation. To avoid that, the scholars say, drug companies likely would stop giving discounts to low-income nations—or leave them unserved altogether.

As befits a topic that is both controversial and important, volumes have been written about the advisability of allowing parallel imports, but much of this work is theoretical. There have been few assessments of the actual effects of this phenomenon, especially in developing countries. In this brief case study, we contribute to this sparse empirical literature by examining the reasons for and consequences of international arbitrage of medicines in the Republic of Georgia, which encouraged the practice via regulatory reforms starting in late 2009.

We find that the regulatory environment and market conditions in a particular country will be key factors in determining whether parallel trade in pharmaceuticals (and presumably other goods for which intellectual property rights issues are important) might be welfare-enhancing. Specifically, Georgia's experience demonstrates that the nature of institutions in a small, developing nation can lead to noncompetitive pricing in local markets, and that regulatory changes—in this case, outsourcing some key processes—that facilitate arbitrage can deliver major benefits to consumers without, apparently, disturbing manufacturers' pricing policies or adversely affecting cost recoupment for R&D efforts.

The Republic of Georgia

Located south of Russia in the Greater Caucasus mountains, Georgia is a nation of 4.3 million people. That is roughly the population of the Phoenix, Ariz. metropolitan area, the 13th largest in the United States. The Georgian economy tanked in the last days of the Soviet Union and the first years of independence from Russian rule: gross domestic product declined 68 percent and inflation hit 1,500 percent between 1990 and 1994. Since then, however, the republic has grown rapidly, with GDP increasing roughly fivefold in the new millennium, prices and exchange rates of the Georgian lari remaining stable, and foreign direct investment increasing steadily. Still, Georgians' per-capita annual income today is less than $6,000, the official poverty rate exceeds 17 percent, and (like many developing nations) Georgia scores relatively poorly on measures of corruption and income inequality, ranking near countries like Nicaragua and Ivory Coast.

Given their modest average incomes, the great majority of Georgians choose not to purchase health insurance. Those below the official poverty threshold and some state employees receive publicly funded comprehensive coverage, while another 120,000 or so purchase government-subsidized private plans. But in recent years 73 percent of Georgians' total annual health expenditures have been privately funded, and 97 percent of that was out-of-pocket. Almost 40 percent of households' total spending on health care was for pharmaceuticals and medical supplies, which are generally not covered expenses under either government or private insurance programs.

Consequently, cost considerations frequently limit Georgians' access to health care and essential medicines. In a 2000 survey, 39 percent of the population that did not receive treatment despite reported cases of illness cited cost as a reason for declining to seek care on at least an occasional basis. Thirty percent of those who had sought care for one reason or another cited expense as a reason they had declined to use a medical service. In 2005, for example, a quarter of children under 5 years of age suffering from acute respiratory infections—responsible for 18 percent of deaths in that age group worldwide—were never taken to a health facility; only half of the children with diarrhea received oral rehydration therapy. Predictably, then, overall health has not improved as rapidly in Georgia as elsewhere in the developing world; since 1990, average life expectancy has risen modestly in absolute terms, from 70.2 to 72.1 years. As a result, Georgia's world rank on this measure has fallen from 61 to 102.

Georgi's Regulatory Reforms

Until 2009, those seeking to import and sell pharmaceuticals in Georgia faced the same regulatory review process as one would if the drugs were produced domestically. Applicants would pay a registration fee and file a two-part form with the Departmental Registry of State Regulation of Medical Activities at the Ministry of Labor, Health, and Social Protection. The subsequent review involved both expense and delay, with a fair amount of back-and-forth between applicant and bureaucracy as technical examinations led to agency demands for corrections. This process was not intended to exceed about six months, but often took far longer (though no data exist on average regulatory lags). In addition, the government required all importers to obtain trade licenses from foreign manufacturers, adding to their costs.

The upshot is that, in a market as small as Georgia, regulatory institutions tilted the competitive field in favor of larger firms, which could amortize their fixed costs over more units sold and more readily tap sources of financing that would help them endure inevitable bureaucratic delays (occasional changes in packaging, for example, required re-registration). As a result, Georgia's pharmaceutical market became oligopolistic. Three large firms—PSP, Aversi, and GPC—sold about 75 percent of all medicines consumed in the country, prices tended to be high relative to Georgian incomes, and the number of therapies on the market were lower than in many other countries.

In October 2009, however, the Georgian government did something remarkable. Recognizing that its regulatory machinery was, in fact, unnecessarily duplicating that in many developed countries, it adopted a new “approval regime.” It compiled a list of foreign authorities with good regulatory track records (including, for example, the European Medicines Agency and drug administrations in the United States, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand), and pharmaceuticals that were approved for sale by those entities could henceforth gain automatic approval for sale in Georgia. In addition, the registration fee was slashed 80 percent for brand-name drugs and packaging regulations were greatly simplified under a new “reporting regime.” Now, for example, when an approved drug’s packaging changes, the importer or distributor is not required to “go back to square one” and re-register the drug.

This regulatory outsourcing compressed the time and greatly reduced the expense required to compete in the Georgian pharmaceutical market, though it was far from complete deregulation. The Ministry still required, for example, substantial documentation about efficacy and labeling, proof of admission in other (certified) countries, and a translation of instructions into Georgian. But the new approval regime invited numerous smaller competitors to enter the market and greatly facilitated international arbitrage. The hope was that this would put significant downward pressure on prices and improve access to drug therapies in the domestic market. It did so very quickly.

Empirical Evidence on the Effects of Reforms

In order to enable an “event study” of these reforms, researchers at the Free University of Tbilisi compiled data on the number of drug registrations, the number of importers, and prices of 30 high-sales-volume drugs sold by two of Georgia’s largest distributers for about a year before and after the new approval and reporting regimes were installed.

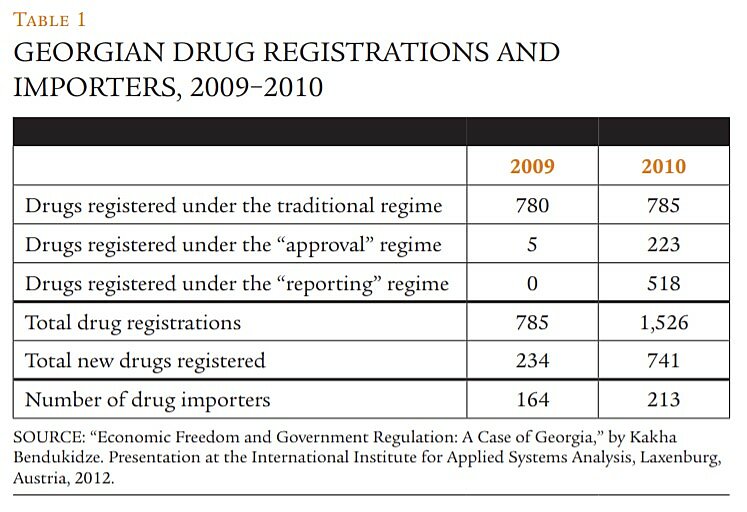

Table 1, which summarizes a portion of these data, suggests that the reforms had favorable and quantitatively significant effects on market entry. Because the reforms took effect in the last quarter of 2009, relatively few drugs were registered under the new regulations that year, but in 2010 the market for pharmaceuticals in Georgia expanded enormously. Total drug registrations soared 94 percent; virtually all of that increase was a result of the new regimes. And though many of the registrations under the reporting regime signal not new therapies but merely a reduction in the cost of distributing newly repackaged drugs, the tally of registrations for drugs reported as “new” more than tripled. Finally, the number of distinct entities acting as drug importers rose 30 percent.

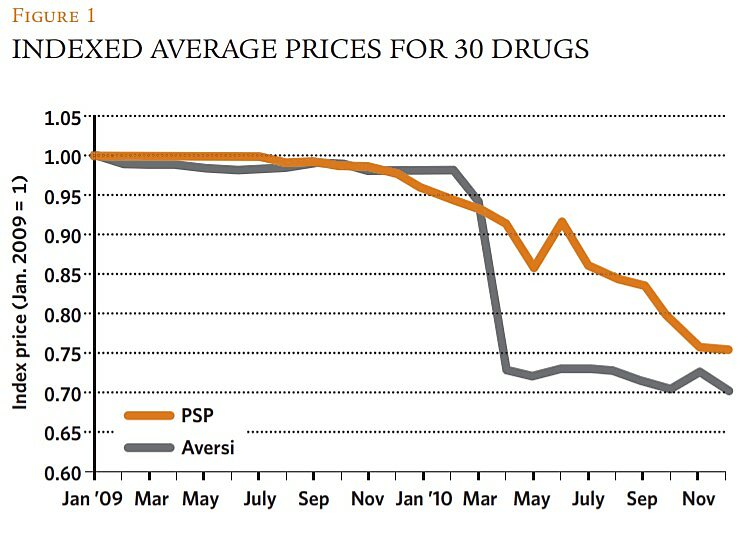

In combination, such data hint that this market became far more competitive in 2010, with many more drug therapies available to Georgian consumers and more small firms vying for their custom. But did this translate into lower prices? Figure 1 suggests that it did; it shows monthly values for an index of the prices of 30 drugs sold by both PSP and Aversi, two of the three aforementioned oligopolists. The drugs sampled span 10 therapeutic classes, from analgesics to urologics, and all prices over 2009–2010 were expressed relative to an index value of 1.0 in January 2009.

Within a few months of the reforms, both firms began to cut their prices, though not at the same pace. Aversi maintained its prices virtually unchanged for four months following the regulatory changes, then slashed prices dramatically, settling at 25 to 30 percent below their pre-reform level for the remainder of the sample period. PSP reduced prices more immediately but more gradually, though it, too, was charging about 25 percent less for this sample of drugs by the end of 2010.

Of course, the timing of these price declines in the period immediately following the regulatory reforms might be mere coincidence or correlated more strongly with other events or influences. Accordingly, we accumulated panel data on a variety of controls and alternative explanatory variables and estimated a regression model to better assess the effects of the reforms on drug prices. Specifically, we tested whether the price changes tracked with a time trend, general deflation, or fluctuations in GDP or exchange rates, and whether they were influenced by type of drug or distributor.

We found consistent evidence that the adoption of the approval and reporting regimes had a statistically and quantitatively significant downward effect on drug prices in Georgia in all model specifications and using all relevant statistical methods (i.e., ordinary least squares, robust, and quantile regression). The estimated models with the greatest power and precision (explaining roughly 55 percent of the monthly variation in prices over the sample period) considered that the passage of the reforms operated on prices with a lag. They concluded that the new regimes reduced prices—all else constant—by about 22 percent, a result that is quite consistent with the story told in Figure 1.

It is possible, however, that those estimated average price declines understate the true competitive impact of the reforms on prices. PSP’s gradual response to the observed market entry likely reflected its competitive strategy. The firm established a daughter company and opened drug stores in proximity to many of the entrants’ pharmacies, reportedly cutting prices more quickly and aggressively in the affiliated stores (though the data used in our regressions do not reflect their prices). PSP may have hoped to maintain segmented markets, charging higher prices in its main stores while discounting in the affiliates—a strategy that in marketing jargon is sometimes referred to as creating “fighting brands.” Figure 1 shows, however, that this hope was ultimately dashed.

Our regressions also showed that the reforms offset some economic headwinds for Georgian consumers. During the period studied, the lari depreciated by about 5 percent against the U.S. dollar and euro, a fact that caused prices of imported drugs to trend upward in the year prior to the reforms. Under the new regimes, however, this trend reversed and, as economic theory would predict (i.e., that elasticities tend to become greater in the long run), the favorable effects on prices became greater over time, with reductions averaging 2.5 percent per month. Further, the price declines were not restricted to certain classes of drugs and none of the macroeconomic control variables had statistically or quantitatively significant effects on prices. In sum, all the evidence is consistent with the Georgian leaders' hopes that the reforms would render the country's pharmaceutical markets more competitive and thus make many more essential medicines affordable and widely available to their citizens.

Longer-Term Worries

What is good for Georgian consumers in the short run, of course, is not necessarily good for them in the fullness of time. Also, what is good for Georgia may not be good for global society. One key concern, as mentioned earlier, is that greater ease of international arbitrage might impair the ability of pharmaceutical manufacturers to recover their steep fixed costs, disturbing a delicate structure of Ramsey prices that generates surpluses in markets where demand is inelastic while permitting prices closer to marginal cost in markets where demand is more elastic. If arbitrage reduces prices and profits in the former, firms might cut supplies to the latter, thus harming consumer welfare there or, in the extreme, reverting to a uniform-price strategy that abandons the more elastic market(s) altogether.

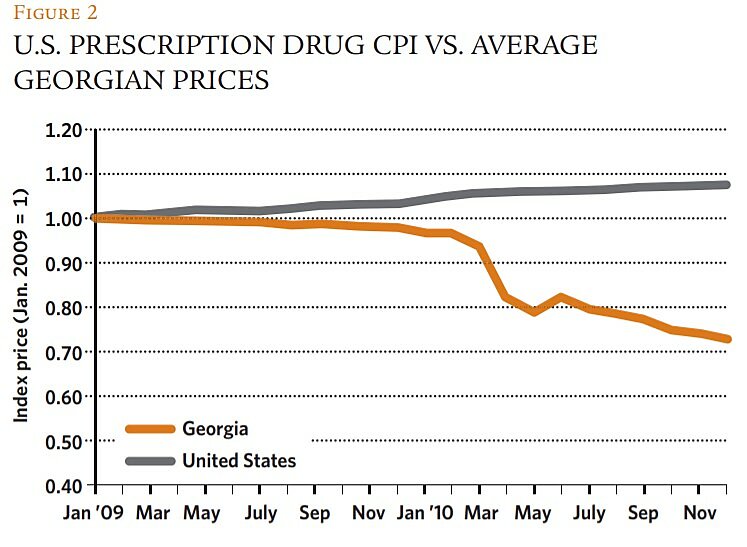

But this worry appears to have little relevance to this case. Given Georgia's modest size and relatively low income (and therefore its high elasticity of demand for drugs), it is extremely unlikely that its formerly high prices had anything to do with cross-national price discrimination by manufacturers. Rather, Georgia's pre-reform price structure simply reflected the law of unintended regulatory consequences: its prior consumer protection program had inadvertently created or preserved local resellers' oligopoly power. Regulatory reform, therefore, likely had no effect on manufacturers' R&D cost recoupment, but simply reduced the rents accruing to the oligopolists. We found no evidence that the reductions in drug prices in Georgia were associated with similar profit-eroding declines in major drug-producing markets. Figure 2 shows that average drug prices in the United States, for example, trended upward throughout the period studied—an unsurprising result given the relative sizes of the two markets.

A more realistic concern is that regulatory reforms that encourage international arbitrage may also invite a higher incidence of counterfeiting or fraudulent sales of ineffective (or dangerous) drugs. The period studied here is of inadequate length to properly assess this issue, but it is worth reiterating that Georgia's new policies were reforms rather than deregulation. In effect, much of the technical work of authenticating drug safety and effectiveness was simply outsourced to larger-scale regulatory bodies, most of which possess sufficiently greater resources as to suggest that overall efficiency might actually increase under the new regimes.

Even under the old system, however, there was some possibility that the pharmaceuticals approved for sale might not be identical to those ultimately produced and distributed. Drugs are archetypical "credence goods" in which it is difficult for buyers to assess the quality of products even after using them. In such circumstances, it is usually not regulation that best protects consumers against fraud, but rather their reliance on the "reputational capital" embodied in firms' brand names. That capital serves as a forfeitable collateral bond that induces suppliers to provide expected levels of quality in order to stay solvent over the long term.

It is certainly possible that altering the competitive landscape via parallel trade may reduce firms' incentives to create or adequately maintain such quality-assuring brand-name capital. Alternatively, enhanced competition in drug distribution and retailing may attenuate incentives to provide important pre-sale information to consumers regarding product safety or warnings about misuse. One careful empirical study of the effect of parallel imports in the European Union found no evidence of quality deterioration in countries with higher levels of international arbitrage, but the issue is certainly worth watching.

Concluding Remarks

Though there are many reasons to be concerned about possible ill side-effects of expanded international arbitrage of pharmaceuticals, the regulatory reforms that enhanced such trade in Georgia must be counted as a success—at least thus far—and should be instructive for other developing countries.

Georgia did not simply jettison regulation and invite unfettered parallel imports of drugs. Rather, the country removed some regulatory barriers to competition that had, by creating and maintaining oligopoly power among its largest pharmaceutical firms, inflated domestic prices. By farming out some regulatory duties to bodies in larger, wealthier states, Georgia's reforms quickly and significantly reduced prices of essential medicines to consumers by making market entry easier and less costly. Thus, price relief came in this case not because parallel trade disturbed an intricate international price discrimination scheme on which R&D cost recoupment and further innovation depend, but simply by enhancing domestic competition.

Of course, the efficiencies resulting from this reform should not be terribly surprising. As noted earlier, Georgia is about as populous as the Phoenix metropolitan area. If Phoenix officials decided they did not trust the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to regulate drug safety and efficacy, and the city set up its own regulatory apparatus, it would be obvious that such needless duplication would significantly increase costs for local distributors and retailers. The added (fixed) compliance costs would tilt the competitive playing field in favor of large-scale local enterprises. There would be an immediate hue and cry to "open up the Phoenix market" to parallel trade, and doing so would likely have effects every bit as favorable as those demonstrated here for Georgia, and without adverse effects on the behavior of innovators.

A key question is whether the Georgian model can be replicated widely, and not simply in developing countries' pharmaceutical markets. Might the lessons learned here apply to, say, central banking? Could some countries benefit in similar fashion by tying their currencies to those of larger countries and, at the least, avoid some duplicative costs in the regulation of their financial institutions and management of their money supplies? Perhaps Georgia's reform efforts will prove valuable not just to the health of its own citizens, but to the well-being of those in many other developing nations.

Readings

- "Economic Freedom and Government Regulation: A Case of Georgia," by Kakha Bendukidze. Presentation at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria, 2012.

- "Parallel Imports and the Pricing of Pharmaceutical Products: Evidence from the European Union," by Mattias Ganslandt and Keith E. Maskus. In The Economics of Essential Medicines, edited by Brigitte Granville, Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2002.

- "Parallel Trade in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Implications for Innovation, Consumer Welfare, and Health Policy," by Clause E. Barfield and Mark A Groombridge. Fordham Intellectual Property, Media, and Entertainment Law Journal, Vol. 10 (1999).

- "The Economics of TRIPS Options for Access to Medicines," by F. M. Scherer and Jayashree Watal. In The Economics of Essential Medicines, edited by Brigitte Granville, Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2002.

- "The Role of Market Forces in Assuring Contractual Performance," by Benjamin Klein and Keith B. Leffler. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 89 (1981).

- "Value-Based Differential Pricing: Efficient Prices for Drugs in a Global Context," by Patricia M. Danzon, Adrian K. Towse, and Jorge Mestre-Ferrandiz. NBER Working Paper No. 18593 (2012).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.