Bitcoin is a private, non-centrally managed “cryptocurrency” that users create and exchange over the Internet via an open-source protocol. The concept of Bitcoin was first made public in a 2008 paper by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto and its first client software appeared the following year. Bitcoin is fascinating for at least three reasons: its technological virtuosity, the light it throws on the nature of money (including the possibility of private fiat money), and its clash with the regulatory state.

On the technological front, “bitcoins” (the capitalized form of the word refers to the overall system, while the lower-case version refers to the actual unit of exchange) are exchanged on a peer-to-peer computer network. “Peer-to-peer” means that participating computers are directly linked to each other through the Internet, without any central controller. Bitcoins are divisible units (down to one hundred-millionth of a bitcoin, or one satoshi) of a digital currency that exists only virtually on the network. Creation (in Bitcoin parlance, “mining”) of a bitcoin, which can be done by anybody with enough mathematical and computer knowledge, requires a lot of computer power, part of which is simultaneously used to process and verify Bitcoin’s encrypted transactions.

Anybody who just wants to buy, sell, or store existing bitcoins can easily create his own Bitcoin account by downloading a version of the client software (see bitcoin.org); there are also less computer-literate methods of using the system. A person can even manage his account using just his smartphone. With an account, your computer or device becomes part of the peer-to peer network.

The Wall Street Journal has tied Bitcoin to “the rise of a digital counterculture,” but real venture-capital money is flowing into Bitcoin ventures. We are witnessing history in the making. Yet, the future of Bitcoin is uncertain.

Private money? | Are bitcoins really money? This question brings us to the second reason for the system’s fascinating character: it helps us understand the nature of money. Money is anything that is generally accepted as a medium of exchange. Anything that has currency in this sense is a currency. Currency—and thus money—is a question of degree. A dollar bill would not be money for a jungle tribe that has no contact with the external world. A dollar bill has more currency in the United States than in northern Canada. As George Selgin points out, bitcoins are not (yet?) currency: they apparently are accepted by thousands of retailers, but those retailers represent only a tiny fraction of market participants. Try to pay for gas with bitcoins—or gold, for that matter—at a randomly chosen service station and you will see what is not money.

Yet Bitcoin’s lightning development suggests that it has the potential to become money. Some 11 million bitcoins are in circulation, and are traded on a number of virtual markets. Bitcoin is a fiat pre-currency.

Taking subjective preferences seriously, Friedrich Hayek envisioned the possibility of private fiat money nearly four decades ago. After all, money is just what people think is money. Even gold has value only because people assign value to it. The challenge with fiat money is keeping its value stable against the inflationary incentives of its supplier—who will find it tempting to just “crank up the presses” to pay bills. Hayek’s response to that challenge was to argue that the supplier of a private currency would have an incentive to fine-tune supply so as to keep price constant—a response that has not satisfied everybody.

In a couple of decades, when the number of bitcoins approaches 21 million, the stock of coins in circulation will become fixed, with no possibility of monetary inflation.

The mathematical wizardry of Bitcoin solves this problem. Bitcoins are mined by computers at an increasing cost in terms of computing power, and that cost will become infinite when, in a couple of decades, the number of bitcoins approaches 21 million. From then on, the stock of bitcoins in circulation will be forever fixed, with no possibility of monetary inflation. Creating new bitcoins will be a mathematical impossibility.

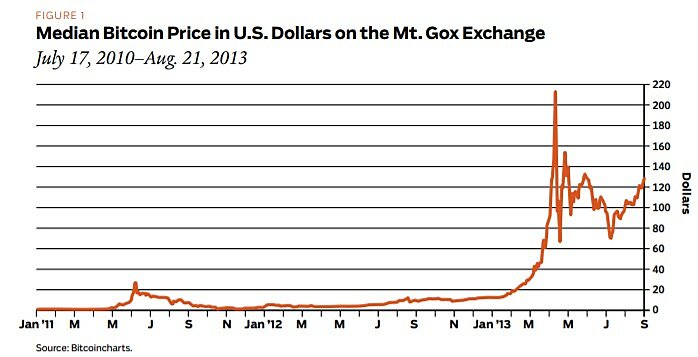

Avoiding government | To get an idea of how Bitcoin enthusiasts see the future of this currency (when and if it becomes one), imagine that bitcoins eventually replace all U.S. dollars and coins. The value of one bitcoin would then exceed $50,000. In the summer of 2013, a bitcoin was worth around $110, so the return on an investment in bitcoins could be mind-boggling. The reality will of course be different: were the dollar to recede, other currencies, whether virtual or not, may compete with bitcoins, pushing down demand for the latter and thus their relative price. Yet it is easy to understand how the upside potential of Bitcoin attracts speculators.

Combined with speculation, the low liquidity of the bitcoin market makes its price very volatile. On a typical day, less than 200,000 bitcoins are exchanged on Mt. Gox, the largest exchange. Between the beginning of 2013 and mid-August, the value of a bitcoin has fluctuated between $13 and $166. Compared to that, even gold looks stable.

With such fluctuations, retailers take a risk in accepting bitcoins. The risk could be minimized if a bitcoin futures market were to develop, but it is far from guaranteed that government regulators would permit it. More generally, Bitcoin is subject to a large regulatory risk.

That brings us to a third issue with Bitcoin: will the regulatory state allow the development of such digital currencies? The prospects do not look good.

We can understand why Leviathan does not like Bitcoin. Since this would-be currency is electronic, encrypted, and peer-to-peer, transactions in it are untraceable. Of course, getting in and out of the system is traceable under current surveillance laws. You come under official eyes when you buy bitcoins with dollars (or any other official currencies) or when you take your bitcoins out of the network. Entry or exit transactions between you and your bank (or other established financial intermediary) are monitored. As long as transactions are made between Bitcoin accounts, however, their authors remain anonymous. There is no central authority necessary to authorize bitcoin transactions and capable of knowing who carries them. The transactions are recorded as anonymous entries in a virtual registry that is synchronized on all computers on the network.

This decentralized anonymity distinguishes Bitcoin from previous attempts at bypassing government surveillance of financial transactions. An early attempt was the Digital Monetary Trust (DMT) created by J. Orlin Grabbe around 2001. As a virtual bank, DMT aimed at offering an encrypted and anonymous platform for storing and transferring currencies—mainly official currencies. Grabbe explained that DMT was “specifically constructed on the principle of ‘don’t know your customer’ ” (bold in original), in direct violation of money-laundering requirements. “Is DMT legal?” he asked rhetorically. His answer is worth quoting: “Is privacy legal? Is encryption legal? If your answer is Yes, then DMT is legal. If your answer is No, then please just go away somewhere and die quietly.”

Aside from suffering from the entry-exit problem, DMT’s centralized character made it less secure. Somebody was ultimately in charge. The system collapsed when Grabbe shut it down after it ran into problems. He died shortly afterward and was never prosecuted by the U.S. government. Some more recent enterprises (such as Liberty Reserve or E‑gold) were not so lucky.

Bitcoin too can be used to avoid money-laundering laws. These laws were adopted to fight the war on drugs and subsequently found another justification in the war on terror. Any cash transaction or export or import of negotiable instruments over $10,000 has to be declared to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, a federal government bureau. Regulated financial institutions have to play cop by enforcing tight know-your-customer rules. A wide surveillance net has developed, which Bitcoin can circumvent.

Governments are also concerned with the tax evasion potential of a parallel monetary system where transactions are untraceable.

Leviathan’s problems would be multiplied if bitcoins were to become a real currency. Governments would have no control over this currency. Monetary policy would be impossible, and so would the inflationary debauchment of the currency used to finance the state.

Governments have thus been trying to bring Bitcoin exchanges and intermediaries under their surveillance systems. They have been intimidated into requiring from their customers proof of identity with official documents. Governments are also forcing the exchanges to register as money transmission businesses. In the middle of the summer, the New York Department of Financial Services sent subpoenas to request information from 22 Bitcoin intermediaries. Earlier this year, the Department of Homeland Security seized two bank accounts tied to Mt. Gox, accusing the company of being “part of an unlicensed money service business.” When Homeland Security attacks Bitcoin, one may ask exactly whose security is being advanced.

The current value (as of mid-August) of bitcoins in circulation is barely over $1 billion, a tiny amount compared to the hundreds of trillions of dollars roaming in financial markets. But this is already a great feat for a four-year-old candidate to the status of fiat currency without any government backing—in fact, under government attack. The future of Bitcoin and other digital currencies depends largely on whether the regulatory state will kill the experiment.

Readings

- Denationalisation of Money: The Argument Refined, by Friedrich Hayek. Institute of Economic Affairs, 1978.

- “Synthetic Commodity Money,” by George Selgin. Social Science Research Network paper 2000118. April 10, 2013.

- “The Economics of Bitcoin,” by Robert P. Murphy. Library of Economics and Liberty, June 3, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.