In an attempt to engender some agency concern, Congress passed the Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) in 1980 with the intent of forcing agencies to identify regulatory alternatives if the cost of any proposed regulation could be deemed excessive. However, despite Congress’s intent to reduce the regulatory burden for business, the current administration has added substantially to the overall regulatory burden.

In order to demonstrate the insufficiency of the Regulatory Flexibility Act as currently written, the American Action Forum looked closely at 10 new rules that, once fully implemented, will significantly affect small businesses. We found that despite the intent of the act, small businesses will find their regulatory burden substantially higher in coming years.

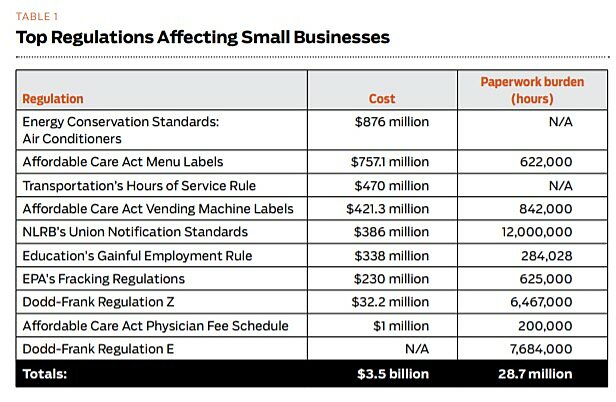

These 10 regulations, listed in Table 1, will impose an estimated $3.5 billion in annual costs and more than 28.7 million paperwork-burden hours—enough red tape to force businesses to hire an additional 14,300 employees simply to file the requisite paperwork. Yet none of the regulations triggered any serious discussion of the contingencies called for by the RFA. That demonstrates the need for Congress or the administration to revisit and amend the act.

Judicial scrutiny | Courts have helped the cause recently, striking down two of the rules that we examined. Judge David Norton, a district judge in South Carolina, found that the National Labor Relations Board exceeded its statutory authority in its union notification rule, which would have required roughly six million employers to post notices informing employees of their union rights. The NLRB failed to conduct a benefit-cost analysis for the rule but admitted that it would burden small businesses. The NLRB then argued that “the social benefits of employees’ (and employers’) becoming familiar with employees’ [labor] rights far outweigh the minimal costs to employers of posting notices informing employees of those rights.” Judge Norton disagreed.

The court defeat of the Education Department’s “gainful employment” rule was perhaps more embarrassing for the Obama administration. The regulation would have forced for-profit educational institutions to meet new federal metrics on debt repayment, imposing a $338 million revenue loss. (Curiously, the rule exempted public and nonprofit schools.) Judge Rudolph Contreras, an Obama appointee, invalidated the regulation because he found the administration’s debt repayment standard was “not based upon any facts at all” and concluded that the regulation was “not reasoned decisionmaking.”

However, the courts are unlikely to invalidate the other regulations on this list, so policymakers must ensure that such rules are not adopted in the first place. This necessitates constructing a regulatory oversight framework that protects small businesses from an administration that is intent on pursuing an ideological agenda regardless of the costs it may impose on the economy or on business. The inability of the Office of Management and Budget’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA)—normally thought of as the gatekeeper for bad regulations—to do this demonstrates the need for some sort of reform that protects small business by providing transparency and a modicum of due process in the regulatory sausage factory that is the federal bureaucracy.

Reforming a broken system | The RFA requires all agencies to certify whether a rule will have a “significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities [SISNOSE]” like small businesses. Agencies must also provide a factual basis for this determination. However, notions of what constitutes a SISNOSE varies widely between agencies, and only one agency (the Department of Health and Human Services) has a quantified standard.

The failure of regulatory agencies to identify what constitutes a “significant economic impact” is an unfortunate legacy of the RFA. Without any discernible metrics to determine significant impacts on small entities, many agencies simply forgo a formal analysis and fail to consult with regulated entities.

The Dodd-Frank financial reform act’s Regulation E is a perfect example of the problems caused by the vague definition of a “significant economic impact.” Regulated entities and the Small Business Administration both requested a small business advocacy review panel to explore alternatives to the regulation, but the newly formed Consumer Financial Protection Bureau rejected their pleas. As a result, the regulation, which imposes more than 7.6 million paperwork burden hours, has proceeded through the regulatory rulemaking process without significant input from small entities or even a rudimentary benefit-cost analysis.

The RFA’s failings have not gone unnoticed in watchdog circles. Both the Government Accountability Office and the Congressional Research Service have studied the failure of the RFA to quantify SISNOSE. In a 2007 report, the GAO found that “there was confusion among the agencies regarding the meaning of key terms such as [sisnose].” In addition, agencies reported that RFA “requirements are less comprehensive than their discretionary reviews because they are limited to regulations with [SISNOSE].” It is clear that agency confusion about key terms do not benefit small businesses or increase regulatory accountability.

The CRS noted that the lack of a quantifiable standard for “significant economic impact” allows dozens of agencies to develop their own standards. This disparate treatment allows the Environmental Protection Agency to determine that 1,760 annual paperwork hours cannot be construed as a burden for a small business. The CRS found one case in which an agency concluded that “thousands of dollars per year on thousands of small entities did not represent a significant burden.” If individual tax burdens increased by thousands of dollars annually, policymakers would no doubt view the impact as significant, but the RFA’s obscure definition ensures that burdens go unnoticed and small business complaints are left unheard.

According to the Small Business Administration’s “Guide for Government Agencies,” only the Department of Health and Human Services has a quantifiable scale for determining SISNOSE: it considers a rule significant if it reduces revenues or raises costs of any affected entities by more than 3 to 5 percent within five years. This would seem like a good starting point for other agencies to establish their own definitions, but the Small Business Administration has reservations about going in that direction, arguing that a one-size-fits-all standard is inappropriate.

Former OIRA administrator Cass Sunstein has placed a renewed emphasis on quantified regulatory analysis. The administration is happy to quantify benefits to justify certain regulatory actions. After four executive orders and countless memos to agencies, there is little stopping the White House from implementing a quantified SISNOSE standard for executive agencies.