For nearly a century, the states of Minnesota, Missouri, New York, and Pennsylvania imposed price ceilings on event tickets sold in the secondary market — the market in which current owners resell their tickets to concerts, sporting events, and plays. When these price ceilings were first imposed, most secondary market trades occurred face-to-face and the resellers were mostly local brokers, scalpers, or hotel concierges. By the time the four states repealed their price ceiling laws in 2007, most trades were being made on the Internet and many intermediaries (i.e., scalpers) had been squeezed out of the industry. According to the Minnesota legislator who sponsored that state’s repeal bill, the move to the Internet made Minnesota’s price ceiling “unenforceable.”

Price ceilings on secondary ticket markets are less prevalent today than they once were, but eight states still have them. Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Rhode Island have price ceilings on reselling tickets to all entertainment events, while Mississippi and New Mexico have them on collegiate games only. But some states are considering re-imposing the bans. For example, the New York legislature must reconsider the desirability of price ceilings because of a sunset provision in its repeal law, one that requires the legislature to endorse the repeal or face having it automatically reinstated.

Debates over repealing (or re-imposing) these price ceilings center on the effect that repeal has had on the price of tickets in secondary markets. During the debate over New York’s repeal legislation, opponents predicted that it would cause prices to “skyrocket.” Proponents disagreed, predicting that prices would change very little or even decrease.

If price ceilings are set below equilibrium prices and are enforced, then repealing them ought to cause prices to rise. However, if they are not enforced because most trades occur out of the reach of state authorities, then repealing them could cause prices on secondary markets to increase, decrease, or stay the same. The last case is the easiest — if buyers and sellers ignore price ceilings because they are unenforceable, then repealing them should have no effect on prices at all.

Repealing price ceilings that are not being enforced will only change prices if they affect the behavior of buyers or sellers in some way. For example, repealing them might increase prices if sellers are using price ceilings as focal points in setting their prices. Alternatively, repealing them might be viewed by potential sellers as conferring legitimacy on secondary markets, inducing them to increase the supply of tickets. Indeed, the repeal legislation in New York included a provision that prohibited sports teams from restricting “by any means the resale of any tickets” bought as part of season ticket packages. Prior to the law, many sports fans believed that they might lose their season ticket privileges if they were caught selling tickets online. Advocates also argued that repealing the price ceiling would further move reselling from the shadowy world of scalpers to the more transparent one of the Internet, increasing the intensity of competition and leading to lower ticket prices.

The effect of repealing price ceilings is an empirical issue, one that cannot be resolved by the application of economic theory alone. In this article, I estimate how the repeal of price ceilings by Minnesota, Missouri, New York, and Pennsylvania affected the prices and quantities of National Hockey League tickets exchanged on Stubhub, which is the leading online marketplace for reselling tickets. I chose professional hockey for three reasons: First, I wanted to focus on some sort of entertainment event — concerts, plays, or games — that occurred both before and after the states repealed their price ceilings. Professional hockey games were attractive because Minnesota, Missouri, New York, and Pennsylvania repealed their price ceilings between the 2006-07 and 2007-08 NHL seasons. Second, I wanted to choose entertainment events that allowed me to compare changes in ticket prices (and quantities) in repeal states with those occurring in states that did not change their laws. Professional hockey scored again because there are seven professional hockey teams in repeal states and 15 in states that did not change their laws over the three seasons that I examined. Finally, I wanted to choose a type of entertainment event for which the criteria of selection into the sample would be obvious, such as all of the American teams of the NHL. This should reassure readers that the results are not being driven by the selection of the sample, i.e., that I did not cook the books by cherry-picking the sample.

My empirical strategy worked well, demonstrating that repealing the price ceilings had only a small effect on the resale price of upper bowl tickets, while substantially increasing the supply of premium tickets (i.e., in the lower bowl of the arena) to secondary markets.

New York’s Report on Ticket Reselling

I began this research shortly after the New York Department of State released its own study of the effect of repealing its price ceiling on ticket prices. New York first imposed a price ceiling on secondary ticket sales in 1922 when Abie’s Irish Rose was the hottest play on Broadway, and repealed it on June 1, 2007 when tickets to Jersey Boys were hard to find. Prior to the repeal, resellers of Jersey Boys tickets were prohibited from charging more than 20 percent over the face value of the ticket. Resellers of tickets to larger events — ones in arenas of more than 6,000 seats — could charge up to 45 percent over face value. After June 1, 2007, the price ceilings were gone, but perhaps only temporarily because of a sunset provision in the law.

The sunset provision originally imposed a deadline of June 1, 2009 for the New York legislature to either endorse the repeal or have the price ceiling automatically re-imposed. On the eve of that deadline, the legislature extended it by a year and ordered the secretary of state to conduct a study of the effects of repealing the price ceiling on the availability and price of tickets. Lawmakers’ directions were explicit, asking for a “comparison of the availability and cost of tickets in [New York] with that of other states where price caps in the secondary market are in effect.”

The resulting report relies on data about the price and availability of tickets for 15 concerts and four shows occurring in 2009 and 2010. Eight of the events occurred in New York and 11 occurred in New Jersey, Georgia, Massachusetts, or Rhode Island, all of which the report categorizes as having price ceilings on secondary ticket sales. The data were collected by visiting the websites of each event’s venue (or its agent) and a handful of online marketplaces for reselling tickets. The report concludes that there is “no conclusive evidence” that price ceilings affect prices in the primary market (i.e., original buyers and sellers) or the secondary market, because “in some instances, tickets were priced higher in New York and in others, less.”

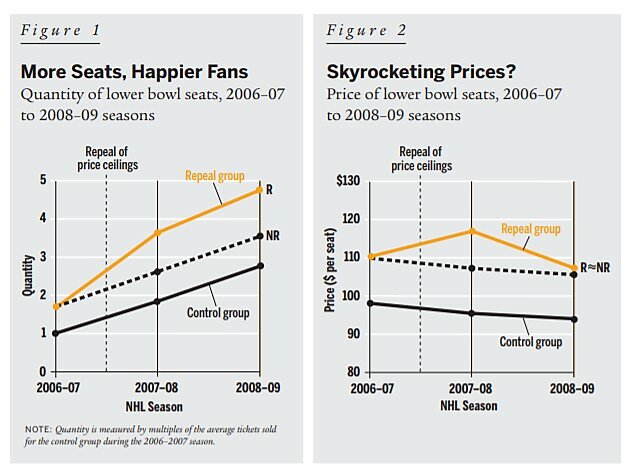

The total number of tickets sold in the secondary market increased in both groups, but repeal states experienced a larger increase.

The report does not present any regressions, so its evidence is not controlling for other factors that might determine prices. The authors do not even present any descriptive statistics because they do not have enough data to create meaningful averages. Their data are incredibly weak, lacking the statistical power to meaningfully test hypotheses about whether (and how) price ceilings affect primary and secondary ticket markets. To their credit, the authors recognize how weak their data are, stating that their analysis “was hampered by [their] inability to compel any segment of the industry to produce valuable ticket sales and availability information on either the primary or secondary markets.”

The analysis was hampered by more than a lack of data. The empirical strategy dictated by the state legislature was inherently flawed, being a cross-sectional comparison of ticket prices in the single state of New York with those in some states that they interpreted as still having price ceilings on secondary markets. The empirical strategy adopted in this article is more ambitious, being designed to have more than one state in the treatment group and to look at changes in secondary ticket markets over time. Fortunately, I also have access to better data than the researchers at New York’s Department of State.

A First Look at the Stubhub Data

Stubhub gave me data on its sales of NHL tickets for three seasons (2006–07, 2007–2008, and 2008-09), one of which was before Minnesota, Missouri, Pennsylvania, and New York repealed their price ceilings and two of which were after the repeals. The data were aggregated by sections of the hockey arenas and only incorporate confirmed transactions, omitting listings that were not sold.

For the Anaheim Ducks, for example, Stubhub gave me the quantity of tickets sold and the total amount paid for seats in the “Plaza Main” section of the lower bowl of the Honda Center for each of the three seasons. While the Ducks carve up their lower bowl into six pricing categories (i.e., sections), the Philadelphia Flyers have only two lower-bowl pricing categories, called “ice row” and “lower level.” This makes comparisons across teams difficult. Hence, I further aggregated the data into upper and lower bowl seats, creating variables on the annual sales and average prices of lower and upper bowl seats for each team for each season.

My sample excludes the Carolina Hurricanes, New Jersey Devils, and the six Canadian NHL teams. I excluded the Canadian teams because they are in a league of their own economically and because they are under a different legal system, one that is harder to interpret. I excluded the two U.S. teams because New Jersey and North Carolina repealed their price ceilings on reselling tickets over the Internet in the summer of 2008, a year after Minnesota, Missouri, Pennsylvania, and New York repealed theirs. Hence, my sample is composed of 22 NHL teams, seven of which are in the repeal group, being located in Minnesota, Missouri, Pennsylvania, or New York, and 15 of which are in the control group, being located in states that did not change their laws over the years of the sample. The states that did not change their laws (and have an NHL team) are Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington, DC.

The graphs tell the story Figure 1 illustrates the trends in the quantities of lower bowl seats traded on Stubhub over the three seasons I examined. To simplify interpretation, I measured quantity using an index, with “1” equaling the average number of lower bowl seats sold on the secondary market in 2006–2007 for Control Group teams. In that same season, the index for Treatment Group teams was 1.78, meaning that nearly twice as many seats of Treatment Group teams were sold on Stubhub.

The top line shows the trend for the seven NHL teams located within states that repealed their price ceilings; the bottom line shows the trend for the other 15 American teams. The total number of tickets sold in the secondary market increased over the time period examined for both control and repeal group teams, but repeal states experienced a larger increase, suggesting that repealing the price ceilings had a substantial and persistent effect on the quantity of lower bowl tickets sold in the secondary market. To estimate the magnitude of the effect, I drew the dashed line, which illustrates how the quantity of tickets sold in the repeal states would have grown had they increased exactly like that in the control states. Hence, my best guess is that sales in the repeal states would have grown to point NR had Minnesota, Missouri, New York, and Pennsylvania not repealed their laws. This implies that repealing the price ceilings increased the quantity of lower bowl tickets traded by 33.6 percent, which is measured by the vertical distance between NR and R. I interpret this as being clearly beneficial for hockey fans in those states, as they obtained more of the tickets that they wanted.

Figure 2 illustrates the trends in the prices of lower bowl seats traded on Stubhub. While the average price of lower bowl seats for games in repeal states increased in the first season following repeal relative to the control states, the difference did not persist over time. As in Figure 1, I drew a dashed line in Figure 2 to trace the path that ticket prices in the repeal states would have followed if they had taken the same course as in the control states. Hence, it appears that repealing the price ceilings did not have much of an effect on the resale price of lower bowl seats.

The empirical evidence summarized in Figures 1 and 2 suggests that repealing price ceilings caused an increase in the supply of lower bowl tickets without having much of a sustained impact on price. It could be that the price ceilings were not binding and the demand for lower bowl tickets is very elastic. Alternatively, any upward pressure on price due to repealing the ceilings may have been offset by an increase in supply.

Repealing the price ceilings appears to have helped fill the seats of the lower bowl of hockey arenas. With a legal ceiling on prices, the owners of “choice seats” in the lower bowl may have chosen to leave them empty on days they could not go to games rather than sell them. They may have felt that the price they could get legally was not worth the hassle. Or they might have worried that the team would penalize them in some way, confiscating their tickets or revoking their right to buy them in the future — a fear that many teams had been promoting. Also, the publicity about the repeal of the price ceiling on secondary ticket sales could have induced some season ticket holders to experiment with reselling their tickets.

A More Nuanced Look

The patterns we see in Figures 1 and 2, however, could be spurious, arising from other factors that were driving prices and quantities on the secondary market, ones that just happened to be correlated with the repeal of the price ceilings. Perhaps, for example, the teams in the repeal states were winning more (or less) in the years immediately after repeal than the teams in the control group, a factor that I will control for shortly. The most important omitted factors, however, are likely to be changes in the prices of tickets in the primary market — the one in which teams set the original face value of the tickets.

Different seats Many NHL teams carve up their arenas into smaller and smaller sections to create more variation in the face value of their hockey seats. For example, the Anaheim Ducks rescaled the lower bowl of the Honda Center prior to the 2007-08 season, adding a new corner section between center ice and goal, subdividing the goal area into upper and lower sections, and nearly doubling the price of “glass” — first row — seats. The rescaling caused the most expensive seat in the lower bowl to increase from being a little less than twice as expensive as the cheapest seat, to four times as expensive. More generally, the average price increased by 35 percent, while the variance in prices nearly quintupled.

Many NHL teams are rescaling their arenas to create more categories of ticket prices, presumably so that their prices better reflect the quality of the seats. Their goal is to capture the profits that are currently being earned by season ticket holders (or speculators) who are reselling many of the most desirable seats within each price category. For example, teams did not always set higher prices for glass seats and only recently has the face value of glass seats skyrocketed relative to other seats. Many diehard hockey fans — the ones who blog about their teams — argue that glass seats “are the absolute worst seats in the house,” because “you cannot see [much].” As one blogger explains, “For hockey you gotta sit farther back and maybe a little elevated to get the best view, preferably around center ice.” Trying to explain the allure of glass seats, an executive for the Boston Bruins argues that sitting up close allows fans to see the true “nature of the sport, how fast it is, guys are getting banged up, cut.” But ultimately, it does not matter why some fans like them. As the executive says, the bottom line is that “there is a market for them.”

Many hockey teams have also adopted variable pricing, which involves setting higher prices for games against marquee opponents, neighboring teams, weekend games, and holiday games. For example, the Detroit Red Wings charge higher prices when they play the Pittsburgh Penguins, and the Florida Panthers charge higher prices during the holidays when a lot of snowbirds are visiting Florida. In defending the practice, teams often emphasize that variable pricing also involves setting lower prices to fill seats during weekdays and when teams are playing less attractive opponents.

The Buffalo Sabres pioneered variable pricing in the NHL, creating four categories of games prior to the 2006-07 season. Two seasons later, they created a super-premium category, called “Platinum Games,” which further increased the variation in ticket prices over the course of the season. Seven American NHL teams currently employ variable pricing: Buffalo, Detroit, Florida, Minnesota Wild, Nashville Predators, St. Louis Blues, and Pittsburgh. One team, the Dallas Stars, has gone a step further, employing dynamic pricing for their upper bowl seats, where prices change continuously, right up to face-off. Stars officials say their goal is to fill seats, especially in the fall when the Stars are competing with college and professional football games.

Teams are also filling the seats, quite literally, by offering all-you-can-eat tickets or food vouchers along with seats in their arenas. For example, several teams sell upper bowl seats with unlimited access to “free” hot dogs, nachos, and drinks. Many teams offer a variety of perks with their premium seats, ranging from upscale buffets to free parking passes.

Most of what I learned about the pricing strategies of NHL teams occurred as I scoured the Internet for seating charts and pricing information. I used the information to create two variables that measure the face value of tickets: one is the average price of non-glass seats in the lower bowl and the other is the average price of seats in the upper bowl. I dropped glass seats from my measure of lower bowl prices because many teams do not publish their prices for glass seats and because they often include perks such as free buffets and parking. I found seating charts for more than one season for every team but one, giving me variation in prices within teams over time. I imputed prices for the missing seasons using the “Fan Cost Index” created by the sports marketing publisher Team Marketing Reports.

Face value and resale I found seating charts with 2008-09 pricing information for 17 of the 24 American NHL teams, giving me face values for many of the tickets traded via the Stubhub website. For lower bowl tickets, the average resale price was $114.00 compared to an average face value of $107.86, a difference of only 5.7 percent. Upper bowl tickets resold, on average, for $53.80, which is 21.6 percent higher than the average face value of $44.20. However, many of the tickets traded on Stubhub were sold for less than face value. For example, the average discount for glass seats (for the nine teams publishing these prices) was 16.0 percent.

The average resale prices of lower and upper bowl tickets sold on Stubhub were less than the price ceilings formerly imposed by New York and Pennsylvania, which prohibited resale prices (to large arena events) from exceeding 45 percent and 25 percent over face value, respectively. Minnesota and Missouri prohibited resale prices from exceeding face value, but allowed sellers to charge a reasonable service fee. Since many tickets were resold for less than face value, the price ceilings would not have been binding for a large majority of the hockey tickets sold on Stubhub. It is debatable whether these legal ceilings even apply to Stubhub sales, since one interpretation of the laws is that they only apply to transactions where the seller and buyer are in the same state.

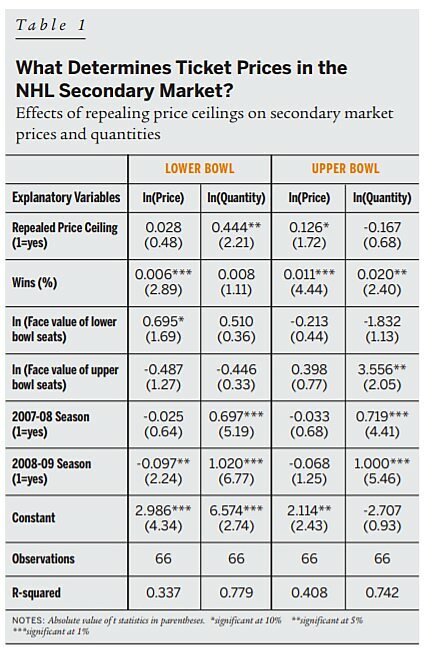

The regressions Table 1 presents the regression results that estimate the effect of repealing price ceilings on secondary ticket markets while controlling for the on-ice performance of hockey teams (measured by wins) and the price of tickets in the primary market. The regressions also include team fixed effects (i.e., dummy variables for each team), ensuring that only the variation within teams over time is being used to estimate the effect of repealing the price ceiling on secondary prices and quantities. This technique also controls for regional differences in tastes, as long as tastes are not changing within the market area of teams over time.

Repealing the price ceilings on the secondary market significantly increased the number of lower bowl tickets traded on Stubhub. In particular, the coefficient on Repealed Price Ceiling in the second regression implies that repealing the price ceilings increased the number of lower bowl tickets traded by 44.4 percent, which is larger than the estimate of 33.6 percent based on Figure 1. The first regression implies that repealing the ceilings did not significantly change the price of lower bowl tickets on Stubhub, which is consistent with Figure 2. While the regression results are technically superior, the earlier graphical analysis is easier to interpret and nicely summarizes the story of how repealing price ceilings affected the secondary market for lower bowl NHL tickets, a story that is confirmed by the regressions.

Repealing the price ceilings appears to have increased the resale price of upper bowl tickets slightly. According to the third regression of Table 1, repealing the price ceiling is associated with a 12.6 percent increase in the price of upper bowl seats, holding the winning percentage and the face value of tickets constant. In contrast, the coefficient on Repealed Price Ceiling in the quantity regression of upper bowl seats is statistically insignificant, meaning that we cannot reject the hypothesis that repealing the price ceilings had no effect on the quantity of upper bowl tickets traded.

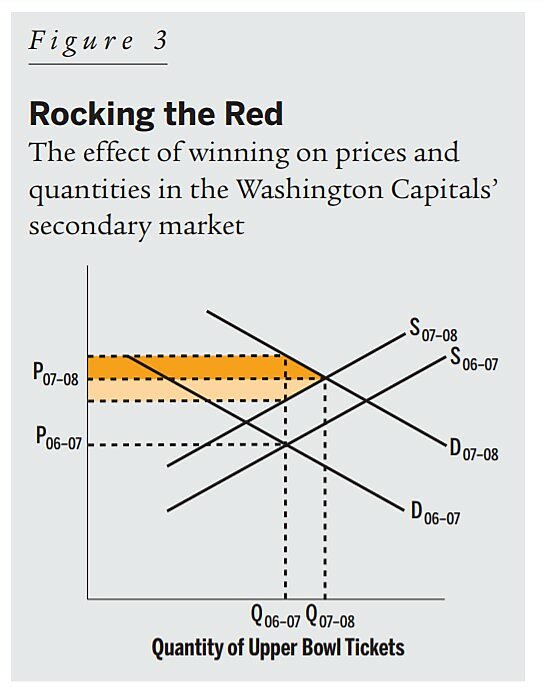

The effect of winning Everybody loves a winner, especially sports fans. Not surprisingly, the regressions find winning more games increases the resale prices of NHL hockey tickets. Consider the case of the Washington Capitals, a team that did not skate well during the 2006-07 season. Despite the presence of budding superstar Alex Ovechkin, the Caps tallied just 74 points and finished last in the Southeast Division. They turned things around in 2007-08, tallying 94 points and capturing the division title. According to the regressions, the improvement in winning percentage increased the resale price of lower and upper bowl seats by 11.0 percent and 20.2 percent respectively, and increased the number of upper bowl seats traded by 36.6 percent.

Figure 3 illustrates my interpretation of the results for upper bowl seats. The Caps’ improved play increased the demand for upper bowl seats in 2007-08, but also increased the opportunity cost of selling them, since sellers were giving up the opportunity to see better games.

The increased opportunity cost of reselling tickets caused a decrease in supply. The regression results imply that the decrease in supply was smaller than the increase in demand, causing the quantity of tickets traded to increase.

The improved play of the Capitals benefited resellers by the amount of the lower shaded region because the price of tickets increased more than their opportunity cost of selling them and because a few more fans were coaxed into reselling their tickets. The improved play benefited buyers in the secondary market by the upper shaded area because their willingness to pay increased more than the price and because a few more buyers were coaxed into the market. Hence, the greater number of wins created more win-win trades.

Primary prices The last time I bargained face-to-face with a ticket scalper was in the summer of 2003. We were in a parking lot outside of Dodger Stadium a couple of hours before a Saturday afternoon game against the last-place Brewers. The scalper offered to sell me three tickets behind the Dodgers’ dugout for $40 per ticket, which I could see was $5 more than the face value of the ticket.

Trying to sound incredulous, I said, “You want me to pay more than face value to see the Brewers play?”

The scalper shrugged his shoulders in a dismissive way and gestured at my daughter’s Dodgers t‑shirt, replying, “Dude, I thought you were here to see the Dodgers play?”

Looking at Emma and her wide-eyed friend, I decided to cut to the chase, offering to pay $35 per ticket.

Cracking a smile, he said, “I can do that.”

The game was great — the Dodgers’ ace Kevin Brown pitched a shutout and the Dodgers won 3–0. As I suspected, few fans came to Dodger Stadium to see the Brewers, causing attendance to dip 21 percent below the season average for Saturday games. Sitting in the stands, I wondered whether I could have bargained for a lower price, but I had no regrets — the girls were having a good time and I thought I had paid a reasonable price for the tickets. In bargaining over price, I was focused on the face value of the tickets, wanting to avoid paying a premium to watch the Brewers but not caring much about maximizing the size of the discount.

One of the reasons that primary prices may affect resale prices in secondary markets is that they serve as focal points in bargaining. Look again at the first regression of Table 1. The coefficient on the ln(Face Value of Lower Bowl Seats) implies that a 35 percent increase in the average face value of lower bowl tickets is associated with a 24 percent increase in the resale price of the tickets. Why did I choose 35 percent? Because that was the increase in the average price of lower bowl tickets that accompanied the Anaheim Ducks’ rescaling of the Honda Center prior to the 2007-08 season. If buyers and sellers in the secondary market respond to increases like this one by changing the focal point of their bargaining, then the regression reflects a causal relationship. However, the relationship might not be causal if changes in some unobserved factor were driving the change in both prices.

Finally, the regressions imply that the quantity of tickets sold on Stub-hub is increasing over time and that prices are decreasing, especially in the lower bowl. In particular, the price of lower bowl seats decreased by 12.2 percent from 2006-07 to 2008-09, a difference that is statistically significant using an F‑test. The estimated trend in the price of upper bowl seats was similar but not statistically significant, because of greater variation in the trend of upper bowl prices across teams.

Limes, Lemons, and Bleacher Seats

In 1795, the British Navy ordered its sailors to begin consuming limes or lemons daily to ward off scurvy, causing British sailors to be given the nickname “limeys.” Suppose the British Admiralty hired you to estimate the effect of its order on the price of lemons and limes. You would not need to worry about distinguishing between the two fruits because consumers viewed them as nearly perfect substitutes. Indeed, the word “lime” was used to refer to both fruits at the time, both being indistinguishable sour-tasting citrus fruits. Hence, the value of a basket of lemons and limes at the time would only depend on the number of pieces of fruit, not its composition of lemons and limes.

In contrast, sports fans can tell the difference between sitting in the first row of a section and the last one. I am writing this in August, a time when the baseball races are heating up. Looking at tickets on Stubhub to an upcoming Philadelphia Phillies game, there is a large premium for first row seats of outfield bleachers — the average price of first row seats is $112 per seat, compared to $75 per seat for the next five rows and $69 per seat for five rows beyond that. Hence, the average price of bleacher seats to particular games will depend on the composition of the tickets offered on Stubhub for each game.

For my regressions, I would have liked to have had data on the resale prices of individual transactions, which would have allowed me to better control for the quality of the tickets. In this case, I would have known whether the seats were in the first row of the upper deck or not. The aggregation of prices and quantities into averages for lower and upper bowl tickets may have created a spurious price effect of repealing the price ceiling for upper bowl seats. For example, suppose the repeal changed the composition of the basket of upper bowl seats, causing it to include more front row seats and fewer back row ones. The higher average quality of the seats in the post-repeal basket would increase the average resale price of upper bowl tickets. Since the regressions do not control for the average quality of the seats, the increase in price would be attributed to the repeal of the price ceilings rather than to the change in quality, creating a spurious price effect.

I would have also liked to have had data on other sports and entertainment events. I would have especially liked to have had more detailed information on the prices in the primary market for each of the three seasons.

Perfection should not be the enemy of the good, especially when decisions are currently being made about repealing or (re-)imposing price ceilings on secondary ticket markets in states such as New York. As far as I know, this is the first study that estimates the effects of repealing price ceilings on secondary ticket markets using data that are rich enough to produce meaningful estimates. I do not include the report done by the New York Department of State because its data are so poor that little can be learned from it.

Conclusion

Many opponents of repealing price ceilings on secondary ticket markets predicted that prices would “skyrocket” if the ceilings were repealed. This article tests their prediction using three seasons of data on the sale of tickets to National Hockey League games that were traded on the Stubhub website. The evidence is clear: resale prices to NHL hockey games did not skyrocket in states that repealed price ceilings compared to states that did not change their pricing laws. Indeed, the evidence implies that repealing price ceilings on secondary ticket sales had no persistent effect on the resale price of lower bowl seats to NHL games and no more than a small effect on the resale price of upper bowl seats.

The fact that repealing price ceilings did not increase resale prices should not be surprising for two reasons. First, the price ceilings are nearly impossible to enforce, given that trades are frequently made over the Internet, often on out-of-state websites. Second, the price ceilings are often not binding because resale prices are frequently less than face value (or not enough above them to bump against the price ceiling), especially for the most expensive seats.

Even if price ceilings have little effect on prices, they still send a message about what society thinks is an appropriate resale price. What is the harm in that? The potential harm is that unenforced price ceilings create unnecessary costs and may have unintended effects. Agencies are assigned to enforce and monitor unenforceable price ceilings, using scarce resources that could be better spent elsewhere. More importantly, unenforceable price ceilings may have unintended effects, such as creating empty seats in the lower bowl of hockey arenas.

This article presents evidence that price ceilings on the secondary ticket market have a chilling effect on the supply of tickets to secondary markets. In particular, repealing them in Minnesota, Missouri, New York, and Pennsylvania was associated with a 36.6 to 44.4 percent increase in the number of lower bowl tickets traded on Stubhub for those teams’ home games. Many owners of premium tickets were reluctant to resell them while there were price ceilings on secondary ticket markets, perhaps because it increased the credibility of threats made by teams to punish season ticket holders who resold some of their tickets.

State governments can send a powerful message by imposing unenforceable price ceilings, one that says that society thinks that some prices are excessive. However, this message can easily be misinterpreted as saying that there is something suspect or even sleazy about reselling tickets in the secondary market regardless of the price. Repealing price ceilings sends an equally powerful message, one that says it is acceptable to resell your tickets in secondary markets.

Then-governor Eliot Spitzer emphasized this message when he signed New York’s repeal law, saying, “I think permitting a free market to work its magic [in the secondary market] is the smart approach.” In the case of NHL tickets, permitting the secondary market to work its magic increased the supply of lower bowl tickets by roughly 40 percent, filling formerly empty seats.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.