My name is Michael Tanner and I appreciate the opportunity to appear today to share my perspective on the question of Medicaid and whether Kansas should expand its program under the Affordable Care Act.

I note at the outset that, for the past 23 years, I have directed health care research at the Cato Institute in Washington, DC., and am the author or coauthor of numerous health care studies, as well as several monographs and books on the subject, including Healthy Competition: What's Holding Back American Health Care and How to Free It. Before that, I served as research director at the Georgia Public Policy Foundation and as director of health and welfare studies for the American Legislative Exchange Council. Overall, I have spent nearly 30 years studying the American health care system. I have been invited here today at the behest of the Kansas Policy Institute.

In my opinion, it would be a significant mistake for Kansas to expand its Medicaid program at this time.

First, a Medicaid expansion would be extremely costly for Kansas taxpayers. While it is true, that the federal government will cover the majority of costs for newly eligible adults under the expansion (94 percent in 2018, phasing down to 90 percent in 2020), you should keep in mind that even 6 to10 percent of a very large number is still a very large number. In fact, the Kansas Health Institute estimates that the 7 year cost to Kansas taxpayers would be roughly $730 million. Expanding that estimate to a 10 year window, suggests that Kansas would have to contribute $1.1 billion.1 These estimates are roughly in line with those put forward three years ago in a report Aon Hewitt prepared for the Kansas Department of Health and Environment.2

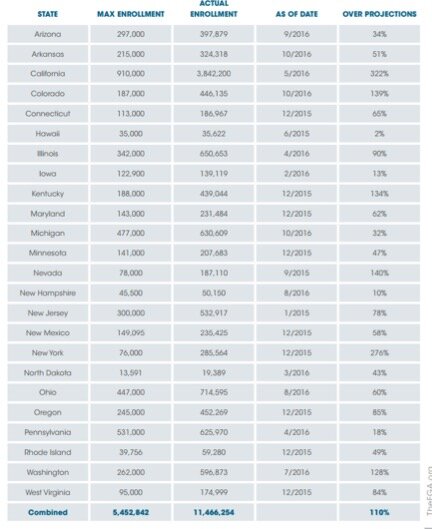

Second, while such estimates are concerning enough in themselves, and would almost certainly require a substantial tax hike to finance, there is ample reason to believe that they understate the actual cost. For example, actual enrollments following expansion have exceeded estimates in every state that has expanded Medicaid under the ACA, in most cases by double digits and in some cases by more than 100 percent. In neighboring Colorado, the maximum projected enrollment was 187,000 and as of October of last year enrollment had exceeded 446,000.3

In addition, the per enrollee cost has risen faster than predicted. From 2014-2015, for instance, the per enrollee cost for newly eligible adults increased by 15.5 percent.

| Eligibility Group |

Per Enrollee Spending 2014 |

Per Enrollee Spending 2015 |

Percent Increase |

|

Children |

3126 |

3389 |

8.4% |

|

Adults |

4695 |

4986 |

6.2% |

|

Expansion Adults |

5511 |

6365 |

15.5% |

|

Persons with Disabilities |

18649 |

19478 |

4.4% |

|

Aged |

14626 |

14323 |

-2.1% |

|

Subtotal |

7202 |

7492 |

4.0% |

Source: Medicaid 2016 Actuarial Report.

While there is predicted decline for 2016, overall health care costs have reversed a decade-long slowdown, and have begun to rise at a faster rate, meaning it is very possible that both the number of enrollees and the cost of per-enrollee care could be significantly higher than current projections.

Third, while it may be tempting to focus on the 94 percent FMAP for newly eligible adults, you should keep in mind that many of those who enroll under expansion will not fall into this category. Rather, they will be previously eligible individuals or families that are lured into the system through the publicity and outreach efforts surrounding expansion. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Urban Institute have dubbed this the "woodwork effect."5 Woodwork enrollees are not eligible for the enhanced FMAP. Instead, Kansas will have to pay 43.79 percent. In states that have expanded Medicaid under ACA, as much as half or more of those who signed up have fallen into this woodwork category.

Finally, it is important to bear in mind the larger national political context. Congress is in the process of drafting legislation that would repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. Congress is also expected to consider legislation, either as part of an ACA replacement or independently, to replace the existing Medicaid program with a block grant. It is very possible that any such replacement plan will, at the very least, reduce the FMAP for people made newly eligible by the ACA expansion. Recall that several years ago, even the Obama administrant briefly considered using a blended FMAP rate instead of the ACA formula. With our national debt of roughly $20 trillion, it would be almost irresponsible for Congress not to take some sort of action to restrain the growth of Medicaid.6 You may well be locking yourselves into future spending based on hopes for federal dollars that may never materialize.

All this expense might be justifiable if it provided quality health care to those who need it most. However, studies have consistently found that people enrolled in Medicaid receive lower quality care, and have worse health outcomes. A landmark study published in the Annals of Surgery examined outcomes for almost 900,000 individuals undergoing major surgical operations from 2003 to 2007. The University of Virginia study found, that surgical patients on Medicaid are 13 percent more likely to die than those with no insurance at all, and 97 percent more likely to die than those with private insurance.7 This trend of lower quality care continues through a numerous studies: Medicaid patients were found to have higher rates of surgical complications, were less likely to have cancer diagnosed at earlier, more treatable stages.8 In almost every health outcome, Medicaid is outperformed by private health insurance.

By far the most important Medicaid study to come out in recent years is the Oregon Health Insurance Exchange study. The reason this study is so important is it is the first randomized controlled study, often considered the gold standard of research, to examine the effects of insurance on health outcomes.

The opportunity for this study arose when Oregon determined that it had enough funds to provide health insurance to an additional 10,000 uninsured low-income adults– but 90,000 people wanted in. Endeavoring to be as fair as possible, the state held a lottery, and then followed these participants over time to measure the impact of access to Medicaid. They found that access to Medicaid increased health care utilization, and medical spending increased from $3,300 to $4,400 per person, but these increases did were not reflected in measured physical health outcomes over the period they were able to analyze. As the authors concluded, "this randomized, controlled study showed that Medicaid coverage generated no significant improvements in measured physical health outcomes in the first 2 years."9

As lackluster as these results are, they are in all likelihood better than they would be in Kansas. Oregon's reimbursement rates are higher than average, and more doctors accept new Medicaid patients. A recent analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Preventionfound that only 68.9 percent of physicians accepted new Medicaid patients compared to more than 84.7 percent of physicians accepting new privately insured patients.10 A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that individuals posing as mothers of children with serious medical conditions were denied an appointment 66 percent of the time if they said that their child was on Medicaid (or the related CHIP), compared with 11 percent for private insurance — a ratio of 6 to 1.11 Even when doctors do still treat Medicaid patients, barriers to access remain, and Medicaid enrollees often have a harder time getting appointments and face longer wait times.

Particularly troubling is evidence that the availability of Medicaid may cause some low-income workers (or their employers) to drop private health insurance, which may be providing higher quality benefits, for the "free" government program. For instance, according to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a review of 22 leading studies on whether the provision of publicly subsidized insurance "crowded out" private insurance found that more than half of those studies showed that expansions of public coverage were accompanied by reductions in private coverage. Some even found that enrollment growth in public programs was completely offset by reductions in private coverage.12

Admittedly, the above studies are somewhat dated. However, there has been no recent evidence to dispute them. More importantly, the high levels of "woodwork" enrollment discussed earlier suggests that crowd out continues to be a problem. Indeed, since Medicaid expansion takes eligibility much farther up the income scale, we can presume that it will overlap even more often with private coverage. It would certainly be counterproductive if this expansion induced individuals with private insurance to swap that coverage for lower quality Medicaid.

For all these reasons, Kansas should exercise extreme caution before expanding its Medicaid program. This is particularly true since there is ample evidence that your state can increase access to Medicaid without formally expanding the program. Since mid-2013, Kansas has enrolled 416,379 individuals in Medicaid and CHIP — a net increase of 10.11%. 13

Major health care reform will have to take place at the federal level. But, If Kansas wants to make affordable health care more widely available to low-income and vulnerable populations, there are many steps that could be taken, from deregulating the practice of medicine to expanding community health centers. Medicaid expansion, however, is a risky gamble, that is almost certain to cost more than you are currently budgeting, while providing surprisingly little to the poor in terms of improved access to health care.

Notes:

1 Kansas Health Institute, "Projected Costs and Enrollment of Medicaid Expansion in Kansas: Updated Numbers," Issue Brief, November 2016, http://www.khi.org/assets/uploads/news/14690/medicaid_estimates_brief_2….

2 Aon Hewitt, "Analysis the Affordable Care Impact to Kansas Medicaid/CHIP Program," March 13, 2015, prepared for the Kansas Department of Health and Environment, http://www.kdheks.gov/hcf/kancare/download/KS_Medicaid_Expansion_Analys….

3 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, "Obamacare Expansion Enrollment is Shattering Projections: Taxpayers and the Truly Needy Will Pay the Price," The Foundation for Government Accountability, November 2016, https://thefga.org/download/ObamaCare-Expansion-is-Shattering-Projections.PDF.

4 Office of the Actuary, "2016 Actuarial Report on the Financial Outlook for Medicaid," Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2016, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/financing-and-reimbursement/downloads….

5 Stan Dorn, Megan McGrath, and John Holahan, "What is the Result of States Not Expanding Medicaid?" Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Urban Institute, August 2014, http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/22816/413192-What-….

6 Bureau of the Fiscal Service, "Daily Treasury Statement," Department of the Treasury, February 3, 2017, https://www.fms.treas.gov/fmsweb/viewDTSFiles?dir=w&fname=17020300.pdf.

7 D.J. LaPar, et al., "Primary payer status affects mortality for major surgical operations." Annals of Surgery. 2010 Sep; 252(3): 544–51.

8 Sarah C. Markt et al., "Insurance Status and Disparities in Disease Presentation, Treatment, and Outcomes for Men with Germ Cell Tumors," Cancer, Vol. 122, No. 20, October 2016, p. 3127-3135, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.30159/abstract; Mark W. Manoso, "Medicaid Status is Associated with Higher Surgical Site Infection Rates after Spine Surgery," Spine, Vol 39, No. 20, p. 1707-1713, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4161632/.

9 Amy Finkelstein et al., "The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year", Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 127, No. 3, p. 1057-1106, https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/127/3/1057/1923446/The-Or….

10 Estehr Hing, Sandra L. Decker, and Eric Jamoom, "Acceptance of New Patients with Public and Private Insurance by Office-based Physicians: United States, 2013," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, March 2015, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db195.pdf.

11 Joanna Bisgaier and Karen V. Rhodes, "Auditing access to specialty care for children with public insurance," New England Journal of Medicine,Vol. 364, June 2011, p. 2324–2333, http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1013285#t=article.

12 Gestur Davidson et al., "Public Program Crowd-Out of Private Coverage: What Are the Issues?" Robert Wood Johnson Foundation 18 Research Synthesis Report no. 5, June 2004, http://www.shadac.org/sites/default/files/Old_files/Crowdout_Brief_Jun0….

13 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid, "Medicaid & CHIP in Kansas," Medicaid.gov, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/by-state/stateprofile.html?state=kansas.