Chairman Hensarling, Ranking Member Waters, and distinguished members of the Committee, I thank you for the invitation to appear at today’s important hearing. I am Mark Calabria, Director of Financial Regulation Studies at the Cato Institute, a non-profit, non-partisan public policy research institute located here in Washington, D.C. Before I begin my testimony, I would like to make clear that my comments are solely my own and do not represent any official positions of the Cato Institute. In addition, outside of my interest as a citizen and taxpayer, I have no direct financial interest in the subject matter before the Committee today, nor do I represent any entities that do.

Let me first commend the Chairman, along with Subcommittee Chair Campbell, on the establishment of the Federal Reserve Centennial Oversight Project. Every government program should be reviewed regularly and subjected to vigorous oversight. The American people deserve nothing less. I can think of no part of the federal government more in need of review than the Federal Reserve. Had vigorous oversight of the Federal Reserve been conducted in the past, we might have been able to avoid the creation of a massive housing bubble.

Monetary Policy and the State of the Economy

The release last week of January’s establishment (employer) survey of employment revealed continued weakness in the U.S. labor market. The 113,000 new jobs estimate was considerably below expectations; for instance the Dow Jones Consensus forecast was 189,000. It was also considerably below the monthly average for 2013 of 194,000. The unemployment rate dipped slightly to 6.6 percent, representing 10.2 million persons unemployed.1

There were a few minor bright spots in January’s labor market. The labor force participation rate rose slightly to 63%, with a 499,000 increase in the civilian labor force. The employment-population ratio slightly increased to 58.8 percent. And total employment, measured by the household survey, increased 616,000. We also witnessed a decline in the number of long-term unemployed by 232,000. Those marginally attached to the labor force, including discouraged workers, remained essentially flat. So while the improvement in the labor market was modest, it was real. Declines in unemployment were not driven, as in previous months, by workers leaving the labor force. That said, our labor market remains weak. Let me say unequivocally, the primary area of weakness in our economy is the labor market.

Over 40 percent of the job growth in January came from the Construction sector, a welcome and somewhat surprisingly increase. Until recently low mortgage rates have largely generated re-financing fees for banks and lower monthly payments for prime credit borrowers, along with higher home prices. The impact on construction and construction employment has been, up until January, quite modest.

There were a few minor bright spots in January’s labor market. The labor force participation rate rose slightly to 63%, with a 499,000 increase in the civilian labor force. The employment-population ratio slightly increased to 58.8 percent. And total employment, measured by the household survey, increased 616,000. We also witnessed a decline in the number of long-term unemployed by 232,000. Those marginally attached to the labor force, including discouraged workers, remained essentially flat. So while the improvement in the labor market was modest, it was real. Declines in unemployment were not driven, as in previous months, by workers leaving the labor force. That said, our labor market remains weak. Let me say unequivocally, the primary area of weakness in our economy is the labor market.

Over 40 percent of the job growth in January came from the Construction sector, a welcome and somewhat surprisingly increase. Until recently low mortgage rates have largely generated re-financing fees for banks and lower monthly payments for prime credit borrowers, along with higher home prices. The impact on construction and construction employment has been, up until January, quite modest.

Outside construction the remainder of job gains were concentrated in professional/business services (+36,000), leisure and hospitality (+24,000) and manufacturing (+21,000). Most of the decline in government jobs was the result of downsizing by the Postal Service. Despite the increase in manufacturing jobs, the average workweek (in hours) and overtime hours declined slightly.

In general the decline in unemployment was shared by most demographic groups, with some exceptions. Teenagers witnessed a slight up-tick in unemployment, as did African-American, Asian and Hispanic workers. December to January witnessed a significant jump in unemployment among African-American teenagers (32% to 39%). This increase is actually understated as the labor participation rate decline substantially for African-American teenagers; had it remained constant the increase in unemployment would have been higher. On an unadjusted (for seasons) basis, the number of employed African-American teenagers fell almost 15 percent from December to January. Seasonal adjustment reduces part of this decline, but not all. It is too early to tell whether this slight increase from December to January was related to a small number of states increasing their minimum wage on January 1st, which generally has a greater impact on the unemployment rate of teenagers. Certainly some of this decline is a result of the end of the holiday temporary hiring, but by no means all. The trend in employment among teenagers merits continued scrutiny as this may offer some indication as the availability of entry-level employment.

While we must address our long term fiscal imbalances, particularly Medicare, immediate policy discussions should begin and end with the labor market. While I am in broad agreement with emphasis placed on jobs, I do not believe our current fiscal, regulatory and monetary policies have been conducive to job creation. In fact I believe all of the above have worked against job creation. We all are aware of the Albert Einstein definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Our economic policies must radically change direction if we are to expect significant improvement in our economy.

The mantra of the Federal Reserve, as well as those who argue for Keynesian fiscal stimulus, is that all of our macroeconomic problems can be fixed if we simply increased aggregate demand. Of course increases in demand can result in increases in employment, holding all else equal. What has made me skeptical of “demand hole” theories of our current macroeconomic environment is that demand, as measured by consumer spending or GDP, has steadily increased since Summer 2009. However employment did not keep pace with that increase, showing a breakdown in what economists call Okun’s Law. One might attribute this breakdown to increased productivity, but that only answers one question with another. Changes in productivity are endogenous to our economy. If the cost of labor increases relative to capital, employers will substitute capital for labor. Of course capital and labor are both substitutes and compliments; whichever effect will dominate at any one time is a matter of a many forces.

One of the inputs to the relative cost of labor versus capital is the interest rate. Lower interest rates generally lower the cost of capital. One hope with traditional monetary policy is that a lower interest rate will spur investment that is complimentary to labor, thereby increasing employment. It is possible as well that declines in the interest rate spur the substitution of capital for labor. Given the recovery in private nonresidential fixed investment, which did follow a “V” shape pattern, and the trend in productivity (real output per hour has increased over 10 percent since 2009), there is some reason to suspect that monetary policy has, in the short run, led to the substitution of capital for labor, perversely increasing unemployment.

Another hope of monetary policy is that reductions in interest rates will increase asset prices by reducing the discount rate at which future cash flows are discounted, in addition to nudging liquidity into particular asset markets. The objective is not to increase asset prices for their own sake, but to create a “wealth effect” whereby households feel richer due to higher asset prices and then increase consumption, increasing aggregate demand and thereby increasing employment. While I believe it is undeniable that Federal Reserve policy has increased the value of a variety of assets, such as homes and equities, and that these policies have exasperated inequalities in wealth (by benefiting current asset owners), I also believe those consequences are not the primary objective of the Federal Reserve. However as Milton Friedman reminded us, we should not judge government policies by their intents but by their results. The result of current Federal Reserve policy has been to inflate asset prices, increase economic inequality with little positive impact on the labor market.

Although current monetary policy has been quite beneficial to the holders of assets, it has not necessarily helped savers. One of the claimed benefits of low rates is that they reduce interest payments by households with debt, and that such reduced payments increases disposable income, which should increase consumption and eventually employment. Indeed mortgage interest payments have fallen on an annual basis almost $200 billion since 20082 . While a significant percentage of that is due to a reduction in overall mortgage debt, which has declined by just over $1 trillion since 2008,3 my estimate is that about $130 billion of that decline is the result of lower rates. But such only tells us half the story. During this same time the interest income paid to households, as savers, has decline by $134 billion.3 The point is that declines in household interest expenses have been off-set by declines in household interest incomes.

One might argue that borrowers have a larger propensity to consumer than savers, which is something we do not know, but even if that were the case, then any increase in spending would be the net of increases by borrowers and declines by savers. In all likelihood this impact would be quite small, a few billions a year at best. There is also some reason to believe the impact is negative as it relates to net aggregate demand. Most of those who re-financed are good credits that did not need a lower monthly payment, while many savers are retired and struggling to get by on fixed incomes. I myself have re-financed my mortgage. And while I am happy to have had my monthly payment reduced, it has made almost no difference on my spending patterns. The point to remember is that a considerable degree of the impact of monetary policy is purely redistributive, rather than wealth increasing. There is some evidence to also suggest that this redistributive is also regressive. In general I do not believe the role of monetary policy should be to take from one group of citizens and give to another.

In general an objective of monetary policy is to stimulate borrowing from the banking system via open market operations. The hope is that expansions in the monetary base will ultimately lead to improvements in the real economy. Since late 2008 the Federal Reserve has engineered a massive increase in the monetary base. This increase led many, including myself, to be concerned about increases in inflation that could result from such an expansion in the monetary base. What some of us failed to appreciate was the extent to which the “plumbing” in our monetary system was broken. For the most part the increase in the monetary base remained in excess reserves held by commercial banks. Cash assets held by commercial banks have increased from under $400 billion in mid-2008 to almost $2.7 trillion. Plenty of liquidity has made its way into the banking system. Unfortunately it has gotten stuck there.

One reason for backed-up plumbing in our monetary system is the Federal Reserve reliance on a small number of institutional counterparties. There are currently only 21 “primary dealers” with which the Federal Reserve conducts monetary policy.5 These are supposed to be the safest of financial institutions, yet previously the set of primary dealers included such entities as Continental Illinois, Countrywide, Merrill Lynch, MF Global, Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers. The downside of this heavy reliance on so few institutions is that when these entities are themselves suffering liquidity problems, their effectiveness as conduits for monetary policy is reduced. They may end up, as Professor George Selgin has labeled them, “liquidity sinks”.6 My fellow panelist former Federal Reserve Vice Chair Donald Kohn has noted:

“The fact that primary dealers rather than commercial banks were the regular counterparties of the Federal Reserve in its open market operations, together with the fact that the Federal Reserve ordinarily extended only modest amounts of funding through repo agreements, meant that open market operations were not particularly useful during the crisis for directing funding to where it was most critically needed in the financial system.”7

The European Central Bank, in contrast, has about 1,700 institutions that are eligible to participate in open market operations. Normally about 300 to 400 do so.8 Such a system leaves monetary policy far less dependent upon the health of a few institutions. It also reduces the potential for bailouts. In being so heavily reliant on only a few counterparties, the Federal Reserve greatly increases the probability that it will provide extraordinary assistance to those counterparties for no other reason than to maintain its ability to conduct monetary policy. It is simply impossible to believe that, as long as the primary dealers number less than two dozen, that the Federal Reserve would allow several to fail at once. In order to improve the conduct of monetary policy and reduce the probability of bailouts, the Federal Reserve should greatly expand its number of counterparties.

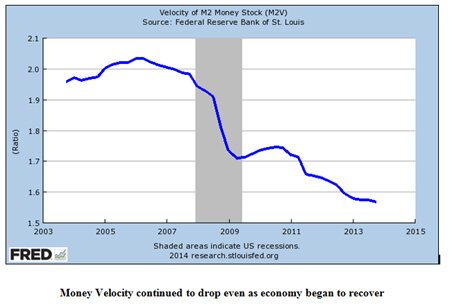

Problems in the financial system are not the sole reason for the relative lack of effectiveness of monetary policy. Another reason that the massive increase in the monetary base has added little to both inflation and economic growth is the dramatic decline in the velocity of money - that is the rate at which money “turns-over”. Since 2006 the velocity of money (M2) has fallen by almost a fourth. While there are numerous reasons for this decline in velocity, Federal Reserve policies may be reinforcing this decline. Among other things, interest rates reflect the opportunity cost of holding cash balances. The lower are interest rates, the smaller the penalty households pay for holding onto cash. Increases in cash balances directly reduce the velocity of money. Perversely enough the Federal Reserves’ current zero rate policies may well be dampening the recovery. The fact is that the economics profession does not possess a clear understanding of the impact of zero interest rate policies. As in other areas, the Federal Reserve’s zero interest rate policies are being conducted largely based upon guesswork.

Although the various rounds of quantitative easing (QE) bear similarities to traditional open market operations, there are some unique attributes that require additional scrutiny. For instance the various rounds of QE resulted in a flattening of the yield curve, which is the difference between short term and long term rates. The summer of 2012 witnessed a difference between the 10 year Treasury and the 3-month rates of 140 basis points. This was down from 380 basis points in the beginning of 2010. While both a too steep and too flat yield curve present problems, the flattening of the yield curve as a result of QE reduced the net interest margin at commercial banks which further reduced the incentive for banks to lend. The beginning of the tapering of QE has resulted in the 10 year-3 month spread rising to above 250 basis points. Not surprisingly this steepening of the yield curve has been accompanied by a significant expansion in consumer credit.9 The Federal Reserve seems to forget that while low rates increase the demand for credit, such low rates will also reduce the supply of credit. If the yield curve continues to steepen, however, policymakers must monitor any increases in maturity mismatch among financial institutions.

No Exit

The Federal Reserve’s unconventional policies have placed it in a difficult position. Normally central banks avoid conducting open market operations in the long-end of the market. They do so for good reason. Conducting open market operations with short dated securities allows a central bank to avoid exposing itself to interest rate risk. While central banks do not “mark to market” they also cannot require their counterparties to purchase securities at par. If the Federal Reserve, in reaction to rising inflation, were to conduct open market operations with its current portfolio of Treasuries and Agencies, it would suffer considerable losses on those securities. While the Federal Reserve could, of course, “print money” to cover its losses, such would add to the very inflationary pressures its tries to stop. In essence the Federal Reserve would be chasing its own tail. The response so far from the Federal Reserve is that this possibility need never arise if those long dated securities are held to maturity. Such is of course true. But then such also depends greatly upon low levels of inflation. As almost two-thirds of the Federal Reserve’s Treasury holdings have a maturity in excess of 5 years, and almost all its agency holdings have a maturity of over ten years, this seems quite the gamble.10 Bizarrely enough the Federal Reserve’s exit strategy may depend upon a continued weak recovery.

The Federal Reserve’s reaction to the above analysis is usually something like: does not matter as we can always pay interest on reserves to constrain bank lending. In a purely mechanical sense that is correct. My estimate is that on current bank reserves of $2.4 trillion, on which 25 basis points in interest is paid, commercial banks are receiving about $6 billion annually in interest on reserves.11 In a more normal interest rate environment this figure could easily reach $20 to $30 billion. In an inflationary environment it could approach $50 to $60 billion. So while mechanically possible, it strikes me as simply politically impossible that the Federal Reserve could pay commercial banks $10s of billions not to lend, especially when that money would otherwise be returned to the Treasury.

In summarize my thoughts on current monetary policy: the Federal Reserve has placed itself in a precarious position. Its exit strategy lacks credibility. Its low interest rate policies have contributed to a rise in asset prices, which are likely to reverse as rates rise. It is unclear what distortions have been created because of these policies, but I believe it’s a good rule of thumb that if you pay people to take money (have negative real interest rates) for extended periods of time, then they are likely to do dumb things with it. Incentives matter. And the Federal Reserve has incentivized some bad behavior, the extent of which we will only discover when these policies unwind.

A central tenet of economics is that all actions have costs and benefits. There are no freebies. The probability distribution of both costs and benefits is unknowable ex ante and likely quite wide. We often do not even know these distributions ex post. I would be the first to say there is some chance that all the costs of the Federal Reserve’s current policies have been worth it. I, however, believe that chance is small; in all likelihood the costs have greatly outweighed the benefits. Of course this weighing depends on one’s discount rate. Only in a World where we place little weight on the future, do current monetary policies seem to make sense.

Policy Issues before the Federal Reserve

In addition to its responsibilities for monetary policy, the Federal Reserve plays a key role in a number of financial regulatory issues. I will conclude my testimony by touching upon a few of these.

Dodd-Frank Title XI

There was perhaps no bigger force pushing the Dodd-Frank Act to passage than the public’s anger with the various financial bailouts. I believe much of the current public distrust towards the Federal Reserve is driven by the public’s surprise that the Federal Reserve could essentially bailout anyone, under almost any terms it chose. Many of us saw the Federal Reserve’s rescue of AIG, assisted purchase of Bear Stearns and various lending facilities as ad hoc and arbitrary. The Federal Reserve, for instance, has offered a variety of contradictory and confused explanations for the differing treatment of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers. Sections 1101 and 1103 of the Dodd-Frank Act attempt to address these concerns by limiting the Federal Reserve’s ability to engage in arbitrary bailouts. While I believe the correct solution is to repeal altogether paragraph 13-3 of the Federal Reserve Act, Dodd-Frank Sections 1101 and 1103 offer a modest avenue for limiting bailouts.

Despite bailouts being a central concern of the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve was late in promulgating rules to implement these provisions. A notice of proposed rulemaking was released just days before Christmas in 2013. The Board and staff must have been in a hurry to leave for the holidays, as the notice largely repeats language from the statute and fails to address the law’s intent to limit Federal Reserve discretion. It is impossible to read the proposal and see how it in any way limits Federal Reserve discretion. All of the actions taken in 2008, which so angered the public, would still be feasible under the proposed rule.

Let me commend the Chairman on his recent letter to Federal Reserve Chair Yellen. Chairman Hensarling’s letter raises a number of important questions. These must be answered for the Federal Reserve to truly comply with the Dodd-Frank Act. Let me touch upon a few of the most important issues.

- Insolvency determination — the rule’s definition of insolvency is exceedingly narrow and does nothing to actually limit Federal Reserve discretion beyond what is already included in Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act. The notion that a firm is only insolvent once it is already in a bankruptcy, resolution or receivership contradicts both common sense and historical practice. The rule has it completely backwards. Bankruptcy does not trigger insolvency, insolvency triggers bankruptcy. Dodd-Frank Section 1101 attempts to limit Federal Reserve assistance to firms experiencing liquidity issues, not solvency issues. The proposed rule ignores, if not contradicts, both the purpose and language of the statute. To be of some assistance to the Federal Reserve, here is the definition of “insolvent” from Merriam-Webster’s dictionary12 :

a. (1): unable to pay debts as they fall due in the usual course of busine

b. insufficient to pay all debts <an insolvent estate>.- Pass-through assistance from solvent to insolvent firms — While it is generally agreed that Bear Stearns was insolvent at the time of its purchase by J.P. Morgan, we should not forget that the actual assistance was to J.P. Morgan, even if an intended beneficiary was the creditors (and shareholders) of Bear Stearns. The rule is silent on in this area. No doubt it is a difficult issue to address. But if Federal Reserve could simply pass assistance to insolvent firms via solvent firms, then the entire purpose of Dodd-Frank’s Section 1101 would be nullified.

- Definition of Broad-based — While I am personally against any bailouts, individual firm or broad-based, the intent and language of Dodd-Frank is to only provide assistance to classes of firms, not individual firms. I have no doubt that the Federal Reserve is clever enough to design programs that appear broad-based but are instead intended for the assistance of an individual firm. We can reduce market expectations of assistance to individual firms if the Federal Reserve commits itself ex ante to a set of rules that bars assistance to individual firms. I do not believe the current proposal achieves that objective.

I believe these three are the most crucial issues to address, but emphasize that all the issues in the Chairman’s letter demand deliberation and response. I also emphasize that the ultimate solution should be a repeal of 13–3 of the Federal Reserve Act. One of the fundamental problems is that the Federal Reserve, as evidenced by its actions and statements of officials, sees the bailouts of 2008 as great successes that should be allowable options in the future. Many officials at the Federal Reserve simply do not share the intents and purposes of Dodd-Frank’s Section 1101. For instance New York Federal Reserve Bank President William Dudley has been quite clear that he believes the problem facing many non-banks is the lack of a government back-stop. In general, the perspective of the Federal Reserve is that most crises are simply liquidity issues that can be solved with government guarantees. The New York Federal Reserve has been quite explicit that it sees the lack of access to government guarantees as the source of fragility in our financial system.13 This ignores that the level of both illiquidity and insolvency in the financial system is not exogenous but driven by the institutional features of the system. It also accepts tremendous long run costs for relatively modest short run benefits.

Basel Capital and Liquidity Requirements

n September14 and October15 of 2013, the Federal Reserve issued interim and proposed rules relating to capital and liquidity requirements under the Basel accords. While the current round of Basel capital rules are improvements over earlier proposals, these rules still retain the fundamental flaws found in earlier Basel proposals. Foremost among these flaws is a reliance on risk-weights that have only a vague connection to actual risk.

I believe our financial system would be considerably stronger if we abandon political risk-weights and simply relied upon leverage ratios. While leverage ratios are not without problems, they reduce regulatory arbitrage, such as that which drove securitization activity. As importantly they also encourage banks to lend to the private sector instead of government. As part of the highly politicized Basel process, sovereign debt is favored over private sector debt. I would submit that the debt of a company like Apple is far safer than the debt of say Greece or Italy, yet the Basel rules take the opposite approach. The risk-weights also encourage banks to hoard into particular assets. They reinforce incentives for bank balance to become homogenized. Such increases the likelihood of fire sales and systemic risk. We should want more diversity in our financial system not less.

The current liquidity rules repeat the mistakes of Basel’s capital approach.16 The heart of liquidity is the ability to find willing buyers when you want to sell. By encouraging banks to all hold similar assets, the liquidity requirements guarantee a large imbalance between sellers and buyers. It appears the actual objective of the proposed liquidity rules is to insure that banks have a large portfolio of assets that the Federal Reserve is willing to lend against.

The recently finalized “Volcker” rule repeats many of these same mistakes. By exempting Treasuries, Agencies and municipal debt, it will encourage herding into those assets. A number of institutions have failed in the past because of heavy reliance on these assets.17 Even if we believe they have minimal credit risk, which is clearly mistaken in the case of agency and municipal debt, the interest rate risk in these assets can pose a significant risk to financial institutions and to the large economy.

Not to be too flippant, but any regulatory system that treats the debt of Fannie Mae, Greece, or Stockton California as “risk-free” is one that is bound to fail and to so miserably.

Whereas I cannot think of a financial crisis that was caused by small business lending, which we all know is quite risky. Our current regulatory framework in regards to capital and liquidity is fatally flawed. Such a system will be a contributor to the next financial crisis. Perhaps worse, it will result in lower long run economic growth as resources are directed away from the private sector and towards government.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

As the Committee is well aware, the Federal Reserve is not required by statute to conduct cost-benefit analysis when it proposes new regulations. I would like to believe we all want new regulations to have benefits that outweigh the costs. As an economist, and one who has worked in a regulatory environment, I would be the first to admit that cost-benefit analysis is far from perfect. Yet it does have generally accepted principles, methods and approaches to data.18 It is certainly no less a science than macroeconomic forecasting. More importantly it pushes regulators to think more clearly about the objectives of a particular regulation and more seriously consider alternatives. Accordingly I believe it is appropriate for the Federal Reserve, and all other financial regulators, to engage in cost-benefit analysis. Certainly the Federal Reserve maintains more than a sufficient number of economists on staff to comply.

Some might argue that cost-benefit analysis is simply an avenue for delay. The same was said of the Administrative Procedures Act, yet I believe it is now without question that notice and comment rule-making has improved the quality of regulation. Nor has cost-benefit analysis constrained the rule-making process at agencies where it has long been used. One of the first agencies to use cost-benefit analysis was the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Cost-benefit analysis has not shut down the EPA and nor has it resulted in a worsening of our environment. There is little reason to believe the application of cost-benefit analysis to financial regulation would play out much differently.

Conclusions

I thank the Committee for this opportunity to share my views on current Federal Reserve economic and regulatory policy. In terms of monetary policy, the Federal Reserve has placed itself in precarious position. Its exit strategy lacks credibility. Its low interest rate policies have contributed to a rise in asset prices, which are likely to reverse as rates rise. The costs might be worth bearing had they delivered significant benefits. I do not believe they have, at least not of a sufficient magnitude to off-set the long run costs. There is considerable evidence to suggest that the Federal Reserve is more the cause of economic instability than it is the cure.

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen is new to her position. Accordingly we do not know what choices she will make. To some extent the Federal Reserve she inherits has no good choices. While she did play a role in constructing the Federal Reserve’s current policies — she is not exactly an “outsider” at the Federal Reserve — we should not let ourselves be too distracted by who sits in the Federal Reserve Chairman’s seat. Congress and the Federal Reserve should move toward a rules based monetary policy that is not dependent upon personalities. On both the monetary and regulatory fronts the Federal Reserve simply maintains too much discretion.

Notes:

1 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Situation, Release February 7, 2014. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

2 U.S Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, supplemental tables. http://www.bea.gov/national/xls/mortfax.xls

3 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Mortgage Debt Outstanding. http://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/releases/mortoutstand/current…

4 U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts. http://www.bea.gov/national/

5 For current and historical list of primary dealers, see: http://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/pridealers_current.html

6 George Selgin, “L Street: Bagehotian Prescriptions for a 21st Century Money Market” Cato Journal Spring/Summer 2012 Vol. 32 No. 2. https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato-journal…

7 Donald Kohn (2009) “Policy Challenges for the Federal Reserve.” Speech delivered at the Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University (16 November).http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbocp107.pdf

8Cheun, S.; Köppen-Mertes, I. von; and Weller, B. (2009) “The Collateral Frameworks of the Eurosystem, the Federal Reserve System and the Bank of England and the Financial Market Turmoil.” European Central Bank Occasional Paper 107 (December). http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbocp107.pdf

9 See the Federal Reserve G.19 Consumer Credit release. http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/current/default.htm

10 For maturity structure of Federal Reserve balance sheet, see Factors Affecting Reserve Balances Release H 4.1. http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/Current/

11 Estimates based upon Aggregate Reserves of Depository Institutions and the Monetary Base Release H.3 http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h3/current/

12 See http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/insolvent

13 See Shadow Bank Monitoring, Staff Report, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, September 2013. http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr638.html

14 For proposed capital requirements see http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/bcreg/20130924b.htm

15 For proposed liquidity requirements see http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/bcreg/20131024a.htm

16For a general overview of the Basel accords and its flaws, see Dowd, Hutchinson, Hinchliffe and Ashby , Capital Inadequacies: The Dismal Failure of the Basel Regime of Bank Capital Regulation. Policy Analysis # 681. Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/capital-inadequacies-…

17 For instance the failure of First Pennsylvania Bank in 1980 was largely due to its holdings of U.S. Treasuries. See http://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/history2-02.pdf

18See Posner and Weyl, “The Case for Cost-Benefit Analysis of Financial Regulations.” Regulation Winter 2013. https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/regulation/2…