It is an interesting time to work in financial services. This month, we are celebrating ten years since the financial crisis, which in its impact was comparable to the Great Depression. While the macroeconomic picture today is much different, with strong growth and record low unemployment, the impact of the crisis on the financial sector was long-standing and continues to make itself felt.

Additionally, the rapid expansion of data analysis, mobile applications, and machine learning among financial institutions over the last decade is transforming not just lending, but asset management, too. Allied with the demands from post-crisis regulation, these developments present a challenge to established depository institutions.

Making predictions without a crystal ball

My talk is about disintermediation and decentralization. These are big words, but they are ubiquitous in today’s discussion of the future of financial services.

According to Investopedia, disintermediation is “the withdrawal of funds from intermediary financial institutions […] to invest them directly.” The same source defines financial decentralization as “a market structure that consists of a network of various technical devices that enable investors to create a marketplace without a centralized location.”

Behind the big words, therefore, lurks a simple yet momentous question: Will financial technology — Big Data, machine learning, blockchains — render incumbent financial institutions — banks, fund managers, stock exchanges — obsolete?

Pretending to predict with any certainty what the banking and broader financial services landscape will look like in 25 years’ time seems like a fool’s errand. Even the best-informed observers in 1993, on the eve of branching liberalization, would have struggled to foresee the scope and speed of consolidation in subsequent years, let alone the contemporary boom in stock investing, mortgage lending and, ultimately, the financial crisis.

I do not presume to have a crystal ball. Nevertheless, there are a number of signs of the long-term direction of travel. They do suggest that depository institutions will face renewed competitive pressure from outsiders. But this may lead to more, not less, intermediation — just like Uber added a layer of intermediation to passenger transport in order to make the market more efficient.

As for decentralization, time will tell if technology can make a fully peer-to-peer economy cost-effective. Right now, it looks like only some degree of centralization of financial transactions can overcome the barriers to cheap and reliable market exchange.

Structural trends in the financial sector

Let me begin with some important secular trends in finance which preceded, but we’re deepened by, the Great Recession, and which have carried on in its wake.

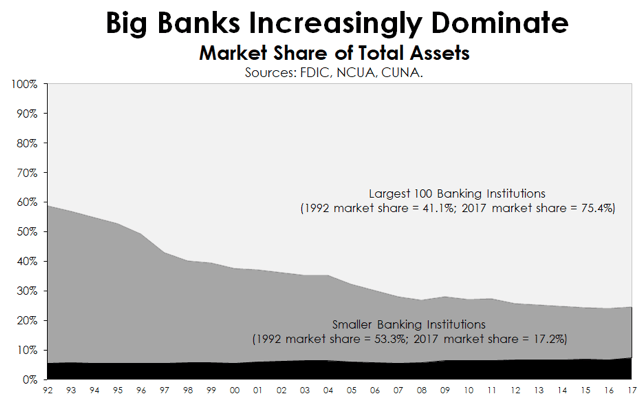

The first is a marked reduction in the number of banks, which dropped to 4,918 in 2017 from 7,077 in 2008, and as many as 10,453 when the Riegle Neal Act (which liberalized branching) was passed in 1994. Credit unions, as you know, have witnessed a similar trend: As of June 2018, there were 5,594 chartered credit unions, compared to 12,333 in 1994.

The decline is in stark contrast to credit union membership, which grew from 67 million to 115 million during that time. Indeed, despite average assets of only $225 million compared to $3 billion for banks, credit unions have managed not only to retain market share but to grow it, from 5.6 percent to 7.4 percent, over the last 25 years.

Source: Credit Union National Association

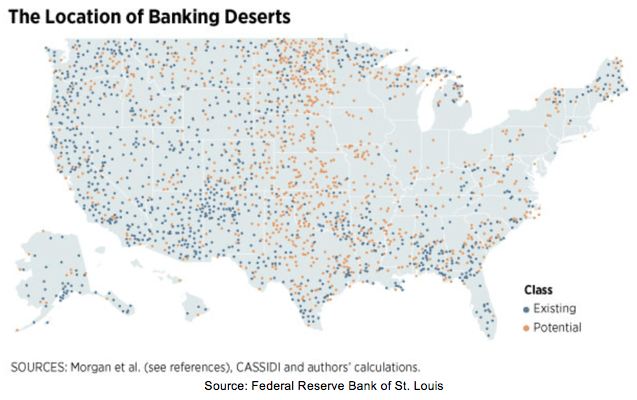

The disappearance of many smaller credit institutions over the last quarter-century has led to the emergence of so-called “banking deserts”: areas without a single bank or credit union branch within a 10-mile radius. Around four million Americans lived in banking deserts as of 2016, with the number set to rise as many small institutions who are the sole physical branches in some communities face closure in coming years. Still, there is reason to believe that community organizations are less prone to branch closures during downturns than are large banks, as they have fewer alternative uses for available capital given the limited geographic scope of their operations.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The extent to which this structural decline in institution numbers is driven by economic as opposed to political factors is in dispute. America for a long time had a high ratio of credit institutions per capita. After 25 years of consolidation, that ratio is closer to other Western markets such as Germany and Spain. The UK, on the other hand, which in its level of financial depth and breadth is most similar to the U.S., has a more concentrated banking market, with the four largest banks holding 60 percent of personal deposit accounts.

Technological advances have probably also contributed to consolidation, since IT systems have high fixed costs but low marginal costs. Furthermore, as firms grow and expand, and as individuals become more mobile, a large branch network gives credit institutions more of a competitive edge.

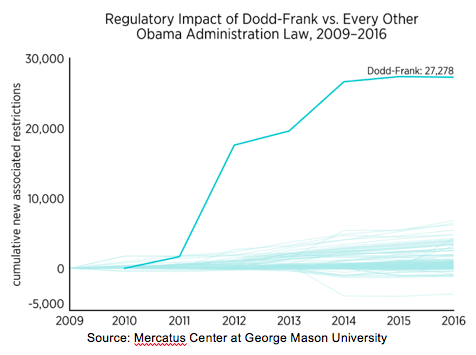

But it’s likely that non-economic factors have also played a significant role, since the second structural trend is a steady growth in the scale and scope of financial regulation. Between 1970 and 2008, regulatory restrictions on credit intermediaries grew fourfold, from around 10,000 to 40,000 on the eve of the crash. The Dodd-Frank post-crisis regulatory package, on its own, piled another 27,000 regulations on the financial sector as a whole — in what has been called “one of the biggest regulatory events ever.”

Source: Mercatus Center at George Mason University

You might think that most of the new rules have prudential motives — higher capital and liquidity requirements; stricter mortgage origination standards; and so on. In fact, a lot of the regulatory growth has to do with increased reporting of suspicious transactions under the Bank Secrecy and USA PATRIOT Acts. While these obligations are justified on grounds of crime prevention, tax collection and national security, there is evidence to believe they are not very effective.

For example, estimates put the cost of enforcing anti-money laundering regulations at between $4.8 and $8 billion annually for the financial system as a whole. Yet, despite a sharp rise in suspicious activity reports by depository institutions, from 670,000 in 2013 to 920,000 in 2017, investigations, prosecutions, and convictions for money laundering have been in steady decline for years.

It is plausible that this drop is due to the fact that copious reporting has discouraged potential felons. A more cynical view, however, is that regulation is simply casting its net too widely — collecting information on perfectly legitimate transactions and pushing up bank compliance costs in the process. That the thresholds for transaction reporting by banks and other financial institutions have not been adjusted for inflation since the 1970s supports the latter interpretation.

The third trend is a shift from deposit-taking to non-depository financial institutions. Quicken Loans recently overtook Wells Fargo as the country’s largest mortgage originator. Marketplace lenders are growing providers of consumer and auto loans. The federal government has taken over the bulk of student lending. Even private equity is replacing banks in their bread-and-butter corporate loan sector.

The extent to which more efficient technology is behind this trend, rather than especially onerous regulation of deposit-taking institutions, is a matter of debate. A 2017 paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research found that regulation explained 60 percent of the growth of so-called “shadow banks,” while better technology accounted for 30 percent. The paper focused on U.S. mortgage markets, which were a chief target of post-crisis regulation. Depositories have retreated from this market, while the role of non-depository lenders and government-sponsored entities has increased.

Small business lending was another victim of the crash. While it has recovered somewhat over the last three years, research has shown that the decline of community financial institutions affected local small business lending. Big banks have not fully replaced them and have themselves restricted small business credit, with measurable impacts on local economic growth and local wages. Even after the economy recovered, these effects persisted where large banks had a large market share.

The challenge of financial technology

Post-crisis supervision has become a burden, especially on smaller institutions. Yet, the trends of consolidation and growth in average asset sizes are unlikely to reverse. Economies of scale are a glaring reality in finance, particularly as more financial activity moves online, lowering the variable costs of operations. On the regulatory front, it will be more difficult to justify relaxing prudential rules on deposit-taking institutions, which enjoy comprehensive government-sponsored insurance, than on “shadow banks,” which do not.

As regulation increases, the “optimum size” of a credit institution will grow. That is because larger banks and credit unions can better bear the fixed compliance burden of much regulation. Entry requirements are another regulatory barrier, and with new bank charters hard to come by and applications becoming ever more cumbersome, increasing demand for financial services can be more cheaply met by an expansion of incumbent institutions than by the establishment of new ones.

Finally, the role of technology in driving a wedge between incumbents and disruptors (plus those who ally with them) is likely to only increase as data collection becomes ubiquitous and machine learning improves. A recent Fed paper found that FICO, the workhorse credit score used for credit decisions in the United States, performed poorly in comparison with Lending Club’s proprietary credit model, which uses FICO but also other variables such as utility payments, internet usage data, and insurance claims. Notably, Lending Club’s predictive advantage has improved as its score diverged from FICO.

The promise of technology

The findings of this paper are interesting for two reasons.

First, making credit decisions from a richer set of data can lead to more accurate estimation of repayment probabilities, resulting in more and better-priced loans. Indeed, the increase in loan volumes and improvement in pricing can especially benefit marginal borrowers who currently face rejection or, alternatively, interest rates high enough to place them in dire straits if anything goes wrong.

Second, and more transformationally, increased use of alternative data can make financial services available to people who would otherwise remain unbanked or underbanked. There are 126 million households in the United States. 29 percent of them are unbanked or underbanked, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation: 9 percent, or 11.3 million, are altogether outside the mainstream banking system, while another 19.9 percent (25 million) have only a basic bank account.

That’s more than 36 million American families whom the banking system is not adequately serving at present.

However, of the 126 million households in America today, 110 million have a broadband connection. 95 percent of Americans have a cell phone. As credit-scoring models incorporate this information, financial institutions will be able to offer affordable products to a larger set of consumers who are now on the margins of the financial system. Better risk assessment technology could halve the number of unbanked and underbanked — and then some.

It’s not just about credit

Fintech is disrupting financial services beyond credit risk. Many of you probably have come across, and use, financial apps on your smartphones. Not only have platforms such as Robinhood, Stash, and Motif made retail investment more accessible and user-friendly, but in the process they are contributing to the downward push on brokerage and management fees that has forced cost discipline on money managers. Minimum investment amounts have also fallen, all the way to zero in some cases, lowering barriers to entry for cash-strapped Millennials.

The impact of app-based entrants has forced incumbents to respond. This summer, Fidelity announced the launch of zero-fee index funds available to customers of all sizes. JP Morgan followed suit with You Invest, an app which (like Robinhood) will allow its customers to trade stocks for free. Vanguard has also expanded its offer of fee-free exchange-traded funds. For 20 years, the battle for investor cash was between active and passive managers. As many underperforming stock-pickers have fallen by the wayside, competition among passive funds has become fiercer.

At a time of historically low interest rates — the lowest since Babylonian times, that is, around 1500 BCE, according to financial historian Richard Sylla — retail investors have snapped up these increased opportunities for cheap capital deployment. Furthermore, the cost savings from moving to zero fees from the 0.25 percent which still prevails across much of the fund management industry can make a 20 percentage-point difference in returns over a lifetime of investing.

Crypto

There is another decennial that we are commemorating in October of 2018. Ten years ago, an enigmatic programmer (or group of programmers) by the name of Satoshi Nakamoto published a paper entitled “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.” Nakamoto proposed to have solved a long-standing challenge of decentralized — that is, disintermediated — payment systems: the so-called “double-spend problem.”

Before Bitcoin, any peer-to-peer system of fund transfers could not easily prevent a user from spending the same funds more than once. Because there was no authority overseeing transactions — making sure that A had the funds that it claimed to have sent to B, that B had received those funds, and insuring A against the possible non-delivery of the good or service promised by B in exchange — peer-to-peer networks inevitably failed under pressure from fraudsters.

Nakamoto’s solution was to use cryptography to make it difficult to steal one’s funds, but easy to verify ownership; an open ledger held by all network participants to log transactions in real time; and a system of rewards that encouraged users to spend time and effort confirming true transactions, while making fraud prohibitively expensive.

I like to compare cryptocurrency networks to market economies. For a market economy to succeed — and history shows that only market-based societies really do flourish — the institutions that govern interactions between people must promote trust and mutually beneficial exchange. In the United States, strong property rights protections give people the incentive to guard and develop economic resources. Contracts make the planning of long-term business and other relationships possible. A reliable court system facilitates dispute resolution. Fraud is punished, both financially and criminally.

This is the atmosphere which cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin seek to replicate, only virtually. Hence the use of cryptography, transparent ledgers, and a sophisticated rewards system for those helping to complete transactions. Whether crypto will manage to one-up established payments and other financial institutions is a question that competition will solve. But those who suggest cryptocurrencies are purely a scam are probably wide of the mark.

Here to stay?

Bitcoin’s birth has spawned thousands of other cryptocurrencies in the ensuing decade. To be sure, the market gyrations of this new asset class can be vertiginous. Just a year ago, bitcoin sold for $4,800. It went on to rise all the way to $19,000 by the end of 2017, only to drop back to around $6,200 as of Thursday [October 11]. I do not purport to give financial advice, but it is safe to say that cryptocurrencies should probably not form a large portion of the portfolio of the typical long-term-oriented, risk-averse investor.

Indeed, cryptocurrencies as a whole still only represent around $200 billion of market value — tiny when compared to the $32 trillion market capitalization of U.S. listed companies.

Furthermore, since the IRS treats Bitcoin and others as property subject to capital gains tax, rather than currency, cryptocurrencies do not make for very efficient exchange media — unless you enjoy accounting for your tax liability each time you use your bitcoin to buy groceries and clothes.

However, the technology has proved to have staying power, despite booms and crashes along the way. Businesses from software giant IBM to shipping conglomerate Maersk to Amazon are exploring internal applications of blockchains, the decentralized ledger technology made famous by Bitcoin. Ripple, the third-largest cryptocurrency in circulation, has set up trials with established financial institutions for international payments, which at present are notoriously slow and expensive. New cryptocurrencies continue to launch despite the bearish cycle: EOS, based in the Cayman Islands, raised $4.2 billion at the end of June.

Regulators rule

The market is pretty good at picking winners and losers. Those who provide a valuable service to customers at a good price make a profit and can continue to serve them. Those who underperform have to choose between swift change or demise. The result is excellence and higher living standards, which have risen 30-fold in the West since open markets started to become the norm in the late 1700s.

Yet, laboring under tens of thousands of rules, the financial services industry is far from a free market. So, regulators will play a salient role in determining the future of financial technologies. The novelty, inscrutability, and volatility of cryptocurrency markets means that regulators are wary to let them grow. That fraudsters have taken the opportunity with this New Big Thing to scam unwitting speculators out of their funds has not helped, either. However, and while condemning fraud, it is difficult to have much sympathy for people who — against every public warning — still bought into crypto, lured by rates of return in excess of 200 percent, without performing the requisite due diligence.

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to make cryptocurrencies synonymous with financial technology. Not only are Bitcoin and its brethren a tiny portion of financial innovation so far, but many of the policy issues that preoccupy lawmakers in the crypto space — crime, anonymity, fraud, and (not least) who on earth is responsible for regulating this stuff — have no parallel for much new lending and investment technology.

Looking at the impact of regulation

Instead, what may stand in the way of the large-scale consumer gains promised by financial technology are long-standing regulations that, while well-intentioned, can hobble innovation and end up harming the people they were written to help.

ECOA, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, is an example. When this statute was written in 1974, lending discrimination was a major concern. Minority communities consistently faced a tougher borrowing environment for reasons unrelated to the credit quality of individual borrowers. ECOA sought to eliminate this unjust state of affairs by banning discrimination on the basis of race, religion, and sex. At the time, it was a forceful piece of legislation that aimed to end, once and for all, a long-standing inequality in the U.S. financial system.

Yet, as the years have passed, not only has racial discrimination in lending declined by leaps and bounds, but the interpretation of ECOA by the courts has expanded. A major disagreement among legal scholars involves whether the statute bans explicit discriminatory practices only — known as disparate treatment — or whether seemingly above-board practices that result in measurably different outcomes for different groups — so-called disparate impact — should also be prosecuted.

As an economist, it is not my place to offer an interpretation of the law. However, I will point out that language that encompasses disparate impact in subsequent financial regulation is absent from ECOA, casting doubt on the contention that a broad interpretation of its provisions is the right one.

Disparate impact — unintended consequences?

Being an economist, however, I am concerned about the consequences of the law, quite apart from the intended meaning of the law. One concern is that a broad interpretation could easily lead to perfectly legitimate practices coming under the spotlight, leading financial providers to exit markets where they currently provide a valuable service. The Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection’s recent investigation of auto lending, which alleged discrimination in loan markups on the basis of what later proved to be shoddy statistical models that would not have impressed my undergraduate econometrics teachers, is an example.

Congress earlier this year voted to repeal the Bureau’s guidance. It has subsequently become clear that its officers were perfectly aware of the weaknesses in their analysis, but proceeded nonetheless under political orders from the top. Given this sort of arbitrary behavior, it cannot come as a surprise that the Bureau’s efforts to promote innovation — dubbed Project Catalyst — have so far received short shrift from lenders.

More concerning even than the consequences of the disparate impact doctrine on existing practices, however, are its effects on future innovation. I mentioned earlier the potential for better credit scoring to increase credit provision at lower interest rates. But such improvements depend crucially on the freedom to test risk measurement models, inserting new variables and taking out old ones to examine their predictive power. If a model can be deemed unlawful on the basis of its short-term differential impact on certain communities, however, the incentive to innovate is diminished.

Furthermore, what’s the point of coming up with new ideas if the regulator will, following a political script, shut them down as soon they are in place?

A disparate impact claim must show that the practice in question has no business justification. In other words, if Asian Americans have higher median incomes than whites, and median income is a useful predictor of ability to repay, then systematically pricing loans to Asian Americans lower than to whites is not discriminatory, since whites are a worse credit risk. Yet, the Bureau conspicuously ignored borrower income and other characteristics relevant to credit risk when it looked at auto lending. Who’s to say that other regulators, and courts, will not behave the same way?

Machine learning is especially vulnerable to regulatory action, since it consists of evolving algorithms that make credit decisions on the basis of reams of data, much of it seemingly unrelated to creditworthiness. When the machine spits out its verdict, it often cannot point exactly to the factor that drove the decision. But watchdogs concerned about disparate impact may not allow technologies that cannot explain their lending policies with minute detail. It would not be the first time that beneficial innovations die from good intentions.

Opening up banking services

Regulators are risk-averse, we can all agree. Because they get little credit for allowing successful new products and much blame for failing to identify trouble spots and potentially fraudulent practices, the people in charge of bank supervision tend to be conservative in their judgements. This is individually rational but can harm the economy as a whole, if it causes promising but uncertain innovations to fall by the wayside due to regulatory overkill.

Sometimes, though, regulation can help innovation and competition in financial markets. Some people believe that will be the case with ‘Open Banking,’ a new regulatory structure for retail financial services provision pioneered in the United Kingdom.

The basic idea of Open Banking is that consumers are trapped with their incumbent providers because competitors cannot access their data to offer better and more suitable alternatives. As a result, consumers remain oblivious to options that would make them better off. The consequence is that retail banking markets are less competitive, and less likely to yield optimal outcomes, than other services sectors — such as groceries and e‑commerce — where suppliers do have ready access to customer data.

Open Banking forces providers to make available their customer data in an interoperable way. With clients’ consent, third-party vendors and data aggregators — notably, mobile apps — get secure access to customer information, which they can scrape and use to offer suitable products. In the same way that Google and Facebook can use your browsing data to place more relevant ads in front of your eyeballs, Open Banking would allow for more targeted credit, savings, and investment product offerings.

The key, as you may have gleaned from the comparison to internet platforms, is how to promote such open access without compromising the security of customer data. Financial accounts contain much sensitive information, which in the wrong hands could facilitate surveillance, blackmail, and — in some cases — even fraud and extortion. Thus, enabling authorized providers to access customer data, but only if they are authorized, is imperative to make the system work.

The UK and other European countries have attempted to resolve this conflict by ramping up privacy regulations — through an enormous legislative package known as the General Data Protection Regulation. Even the largest tech firms have struggled to comply, but the most onerous burden falls on smaller services and apps who now must ask for user consent for the most mundane forms of data collection.

It remains to be seen whether the benefits from greater competition will outweigh greater compliance costs from the new privacy rules. Privacy is not the only challenge to Open Banking: If there is a data breach in the dealings between financial institutions and third-party vendors, who will be to blame? Who is liable for compensation? Will users know with whom the fault lies? This is important, because without adequate customer awareness, the reputational damage from data breaches may fall on perfectly innocent shoulders.

This is what disintermediation looks like

Despite the implementation challenges, something akin to Open Banking is bound to arrive on these shores in the near future. The recent Treasury report on nonbank financials and fintech praised the British model, while noting the differences to laws and practices in the United States. The report encouraged increased data-sharing by financial institutions with customers and authorized third parties. It also stressed the need to define liability. Crucially, it expressed a need for standards that facilitate data-sharing and left the door open to standard-setting by federal authorities if the private sector does not deliver them.

With or without the intervention of public authorities, a growing partnership between fintech firms and data aggregators, on one hand, and financial institutions, on the other hand, looms on the horizon. It will mean that traditional banking relationships, in which retail customers held their deposit account, money market account, retirement account, mortgage and auto loan, and other financial products, with the same firm will gradually cease to be the norm. Instead, switching and arbitrage by consumers, enabled by better information and easier access to competing platforms, will grow.

The upshot is that depository institutions, not least credit unions whose business model is predicated on direct relationships, common bonds, and a lifetime link with customers, will face the challenge of outside firms with lower costs, able to lure customers away with customized offerings at low prices. That does not mean the days of established financial institutions are numbered, nor that the impact of financial technology will be uniform across all banks and other depositories. Already there are important differences in the technological readiness of some institutions compared to others. The coming years will only underscore that contrast.

Pioneers of disintermediation

Should credit unions be afraid of disintermediation? History offers grounds for optimism. Not only have credit unions, as we saw earlier, managed to grow their market share of banking assets even as small financial institutions as a whole lost ground; but they were pioneers of financial disintermediation over 100 years ago.

Originating in England, Germany, and Austria as cooperative banks during the 19th century, credit unions came to America via Canada at the start of the 1900s. Alphonse Desjardins, who had set up one such credit institution in Quebec, helped to establish the first American credit union in New Hampshire in 1909.

That is all well-known to you. What may perhaps be less obvious is that credit unions championed a form of disintermediation of their own. By pooling the savings of communities and groups who shared a common bond, credit unions dispensed with the middleman and were able to offer more competitive rates to borrowers and better returns to their members. Peer-to-peer lending has a modern ring to it, but it would not have seemed an alien concept to Desjardins if it had been explained to him more than a century ago.

The upshot is that the future of financial services is likely to give consumers more power, in the form of data and information. It will not spell doom for intermediaries, but will instead create space for new intermediaries who collect, sift through, and disseminate information, adding value in the process. Decentralization will be a feature of the process, as consumers bank, borrow, and invest with a larger and more diverse set of providers than ever before. But financial institutions are unlikely to become redundant anytime soon.

Regulatory trends will shape these developments. As we have seen, zealous regulation can slow down and even halt financial innovation. Regulatory accumulation can also have an impact on the structure of the financial industry and its costs. The credit union sector has, in aggregate, withstood the onslaught of financial regulation since the 1970s rather well, but within the sector, a secular trend of consolidation akin to that of banks has taken place.

Financial institutions anticipate the advent of new financial technologies with a mixture of excitement and apprehension. To the extent that innovation is likely to give some firms a competitive edge over others, such ambivalence in the face of uncertainty is understandable. The industry as a whole, however, may be more adversely affected by regulatory developments. It behooves us all to ensure financial regulation evolves with technological change, and that policymakers focus on the consequences, and not just the intent, of the rules they write.

Thank you.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.