Housing affordability has become a high-profile issue in recent years as sustained economic growth has pushed up housing prices in cities across the nation. One often-overlooked factor affecting affordability is the reduction in housing supply growth relative to housing demand growth that stems from restrictive zoning and land-use regulations. The extra costs and delays created by these rules have stifled the development of single and multifamily housing in many cities, which have combined with rising demands to raise prices substantially.

Land-use regulation is an umbrella term for rules that govern land development, and zoning is an important type of land-use regulation (Appendix A). Zoning and land-use regulations control the development of private land through use, density, design, and historic preservation requirements. The volume of these regulations has grown markedly over the decades in most U.S. cities. Local governments impose the rules and then enforce compliance via lengthy approval processes overseen by planning commissions or local government administrators. These processes give officials substantial discretionary power, which adds uncertainty to an already costly process for developers and builders.

The growing number of rules and regulations on urban land use has stemmed from well-intentioned efforts to promote public safety, environmental objectives, and aesthetic goals for development. But a major side effect of this growing volume of rules has been to deter construction and reduce the supply of housing, including multifamily and low-income housing. With reduced supply, many U.S. cities suffer from housing affordability challenges.

The deleterious effects of this regulation extend beyond higher housing prices: artificially inflating housing costs discourages migration from rural or suburban areas to cities, which impedes appropriate matching of workers and jobs while limiting the scope of economies of scale and the scope of particular types of economic activity. Thus, these regulations impede economically efficient population density and population allocation.

This study reviews evidence on the effects of zoning and land-use regulation in three related areas: housing supply, housing affordability, and economic growth. The academic research on property regulation indicates that increased regulation is associated with a decline in supply, affordability, and growth. The literature indicates the effects are large, with a recent study suggesting that—because of regulation—economic growth declined by 50 percent and economic output declined by 8.9 percent between 1964 and 2009.1

This paper then provides supporting evidence that regulations have grown substantially over the decades and that the growth is associated with rising home prices. I used a data set of state-by-state court decisions on land use and zoning, which provides fresh evidence for the link between regulations and housing prices. My statistical results indicate that rising land-use regulation is associated with rising real average home prices in 44 states and that rising zoning regulation is associated with rising real average home prices in 36 states. In general, the states that increased the amount of rules and restrictions on land use most have higher housing prices.

These are important results for national policy discussions because the federal government provides more than $44 billion a year in rental aid. And this federal aid may be discouraging states from solving their own housing affordability problems. I examine that issue by comparing state-by-state growth in zoning and land-use regulations to the volume of federal aid received by each state. The results indicate that relatively more federal aid flows to states with restrictive zoning and land-use rules, perhaps because those states have higher housing costs. Essentially, then, federal aid is subsidizing burdensome local policies.

The study concludes, therefore, that policymakers can tackle housing affordability problems at the state and local levels by overhauling zoning and land-use rules. They can cap or reduce local regulation, fast-track approval processes, and compensate property owners for regulatory takings. Additional federal aid is not the answer, and it may even undermine incentives for local governments to make needed reforms.

Local planning and zoning regulation directs the design and development of buildings, neighborhoods, and cities. These regulations are contained in a zoning ordinance, which typically determines the height, width, and architectural features of development under its jurisdiction. It also determines landscaping, character, and use of property.2 Sometimes, it determines that the property has no permissible use at all.

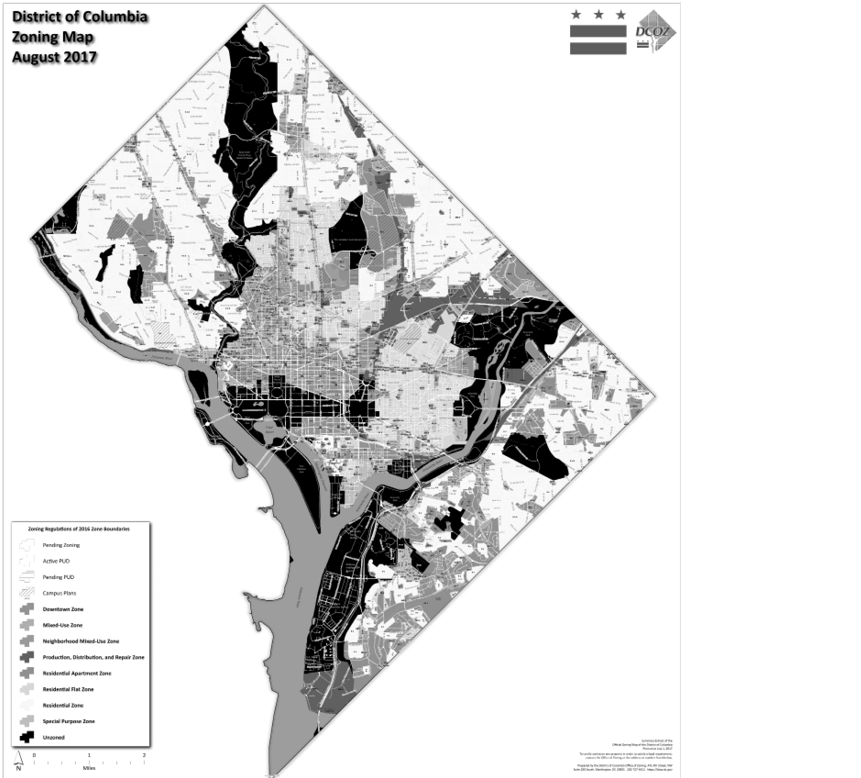

This class of regulation is most recognizable by the colorful zoning maps that often accompany it. Zoning maps separate property into areas (or zones) where different types of development are permitted or prohibited (Figure 1). The colors represent the underlying properties’ allowable use (e.g., industrial, single-family residential, retail/commercial, etc.) and associated development requirements. The regulations apply to properties in urban, suburban, and semirural areas.

Much of the power to regulate and oversee development is vested in local entities. Planning boards are usually authorized by the state legislature, and individual members are elected or appointed locally. Planning boards are generally assisted by professional government planning staff in producing planning documents. The regulations contained in city plans are long term and geographically comprehensive.

Figure 1: District of Columbia zoning map, August 2017

Source “Summary Zoning Map—Ward 1,” District of Columbia Office of Zoning,

https://dcoz.dc.gov/.

Note: Map has been converted to black-and-white for publication. The original was in color.

Implementation of plans is then overseen by planning boards, zoning boards, and local professional government planners. Planning boards can bargain with would-be developers and exact concessions in exchange for approval. Zoning boards provide discretionary oversight and review requests to grant exceptions to the official plan for development.3 Professional government planners assist in the process.

Although the bulk of zoning and land-use planning happens at the local level, federal and state incentives can play a role. For example, federal and state governments often provide grant money in return for compliance with specific objectives. The National Flood Insurance Program provides an example.4 In some cases, federal and state regulations may interact with local planning processes to make regulations more restrictive or exclusionary. Federal environmental laws, such as the National Environmental Policy Act, have broadened local residents’ veto power in the planning process.5

Planning and zoning regulations have been adopted widely, and nearly all properties in urban, suburban, and semirural areas are subject to such regulations. As a result, they control what planners call the “built environment,” or the manmade environments where people live, work, and play. Many features that residents take for granted in cities—from the number of parking spaces at the mall to the location of the nearest grocery store—are a result of this comprehensive, long-term planning.

It wasn’t always true that zoning had such broad jurisdiction. Comprehensive zoning and land-use planning were mostly unknown in America prior to the 20th century. Property rights remained intact, and the courts adjudicated disputes between landowners.

Invention of the automobile and adoption of bus transportation changed that.6 Neighborhood traffic became increasingly difficult to control. Communities could not isolate their homes from people or uses they would like to keep out. Los Angeles is generally credited with the first large-scale municipal zoning and land-use regulation,7 adopted in 1908—the same year the Model T was introduced.

Zoning spread quickly. By 1926, 68 additional cities had adopted it.8 Two years later, the Supreme Court issued a ruling supporting zoning as an expression of police power.9 Perhaps encouraged by the ruling, another 1,246 municipalities adopted zoning in the 10 years between 1926 and 1936.

Controlling neighborhood traffic and development and protecting home values have always been important objectives. But over the course of a century, zoning has become the tool for a broader range of goals. Modern zoning ordinances often aim to protect the environment and farmland. They also endeavor to improve public safety; create aesthetically pleasing, dynamic urban environments; and ensure plentiful low-cost housing—all while allowing communities to control their property tax base.10 Unfortunately, many of zoning’s stated objectives conflict with each other.

Governments adopt land-use regulations for a variety of well-intentioned purposes, but the effects are not all positive. The regulations complicate or prohibit housing development, which reduces supply. Basic economic theory suggests that if demand is rising, then housing prices will increase the most in cities where supply is the most constrained by such regulations.

Empirical research across U.S. cities suggests that, indeed, zoning rules reduce supply, which in turn increases prices. Economist Jonathan Rothwell indicates that “roughly 20 percent of the variation in metropolitan housing growth can be explained through density regulations,” and that “anti-density regulation inflates prices in the face of demand shocks.”11 Economist Jenny Schuetz suggests that zoning regulations decrease the number of building permits issued, especially for apartments and condominiums.12

Zoning regulations restrict supply in many ways. Minimum lot size requirements, for example, reduce the density of housing and thus the overall supply. One study for Boston found that each additional acre of minimum lot size requirement is associated with a 50 percent drop in building permits.13 Building height restrictions also limit supply. And some cities directly limit supply by capping the annual number of building permits.

Zoning ordinances also impose design requirements on housing, which can increase costs because of the need to use more expensive building materials. Like most zoning regulations, design requirements can also increase the duration and uncertainty of the development process, which in turn raises costs. Design requirements may increase the cost of materials for development.

The total number of regulations seems to matter. A study by John Quigley and Steven Raphael estimated that each regulation in Californian cities is associated with a 4.5 percent increase in the cost of owner-occupied housing and a 2.3 percent increase in the cost of rental housing.14 A broad review of the academic literature by Keith Ihlanfeldt found the evidence strongly suggests that zoning regulation increases the cost of housing within suburban communities.15 Research on urban markets found similar results.

Regulatory costs hit some U.S. cities harder than others. Edward Glaeser and coauthors estimated that zoning rules pushed up the cost of apartments in Manhattan, New York; San Francisco, California; and San Jose, California, by about 50 percent.16 A study by Salim Furth found that residents of high-cost coastal cities would pay 20 percent less in homeownership costs and 9 percent less in rent if cities adopted zoning regulations typical of the rest of the country.17

Areas of the country with the strongest economic growth have some of the costliest zoning and land-use rules. Cities such as San Jose have rising incomes and excellent opportunities for workers, but they have severe housing affordability problems. Lower-skilled workers cannot afford the high housing costs in such heavily regulated cities, and so they get stuck in lower-cost areas that have fewer job opportunities.18 Thus, land-use zoning is contributing to a sort of geographical segregation by income.19 Many studies find that zoning is a regressive policy because the costs fall disproportionately on low-income households.20

The overall effect of land-use regulations on the U.S. economy may be quite large. If workers cannot afford to live in places where they can put their skills to the best use, U.S. productivity will suffer. A study by Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti estimated that the mismatch between regional labor supply and job opportunities caused by land-use rules had the effect of reducing U.S. economic output by 8.9 percent.21

This section provides supporting evidence that land-use regulations have grown substantially and that the growth is associated with rising home prices. Quantifying the volume and effects of zoning and land-use regulation is difficult. I use a data set of state appellate court decisions that include the words “land use” or “zoning” as a proxy for regulation and run two parallel analyses: one for land use and one for zoning.22

The number of court decisions on land use or zoning is a good proxy for regulation because important land-use and zoning decisions are usually challenged in court. Daniel Shoag and Peter Ganong note that “[land use] rules are often controversial and any such rule, regardless of its exact institutional origin, is likely to be tested. . . . This makes court decisions an omnibus measure, which captures many different channels of restrictions on new construction.”23

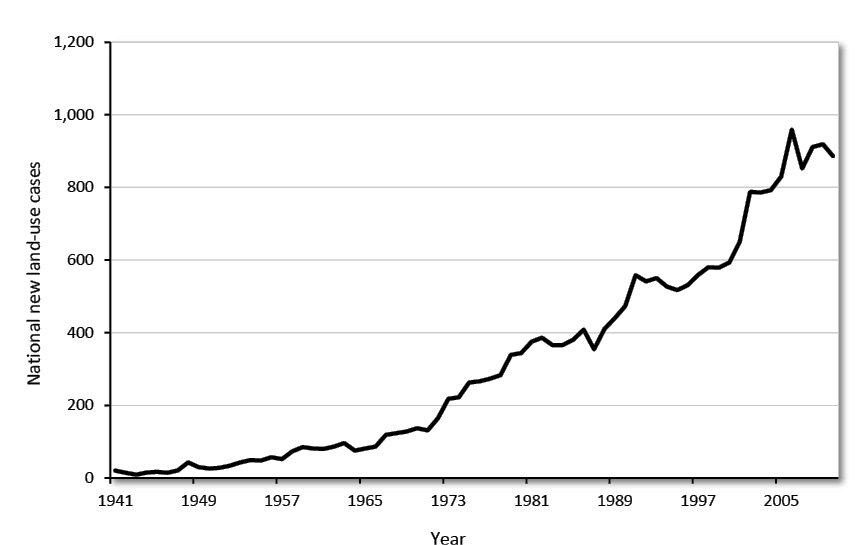

Figure 2: Land-use regulation growth over time: national (1941–2010)

Source Unpublished dataset generously provided by Daniel Shoag of the Harvard Kennedy School. Copy in author’s files.

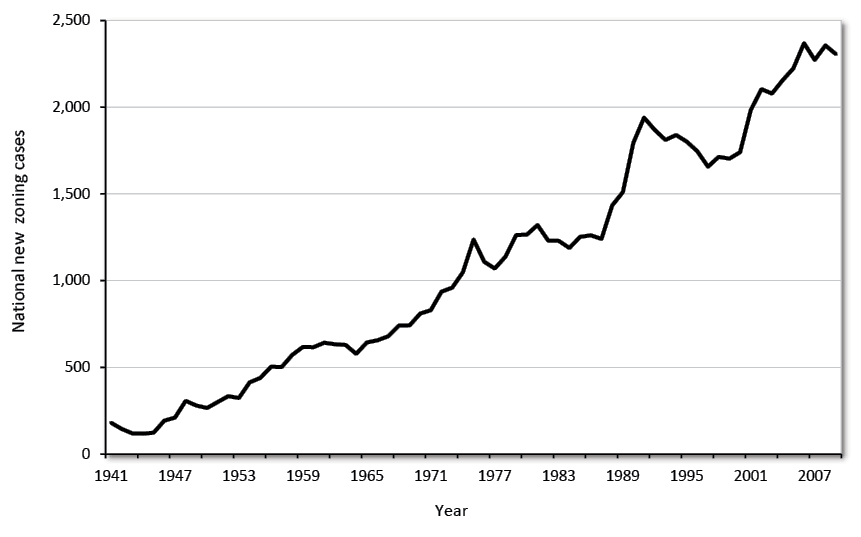

Figure 3: Zoning regulation growth over time: national (1941–2010)

Source Unpublished dataset provided by Daniel Shoag of the Harvard Kennedy School. Copy in author’s files.

The data show that land-use and zoning court cases have increased substantially nationally, as shown in Figures 2 and 3. For example, there were 157 percent more land-use cases in 2010 than there were in 1980. There were 82 percent more zoning cases in 2010 than in 1980. In other words, the number of land-use cases more than doubled and the number of zoning cases nearly doubled over three decades.24 The U.S. population grew 37 percent during the same period. This suggests that zoning and land-use regulation have grown substantially in real terms.

Land-use regulation also grew in all 50 states, as measured by associated court cases, and zoning regulation grew in all states. The annual quantity of new land-use and zoning regulation continues to grow in a majority of states.25

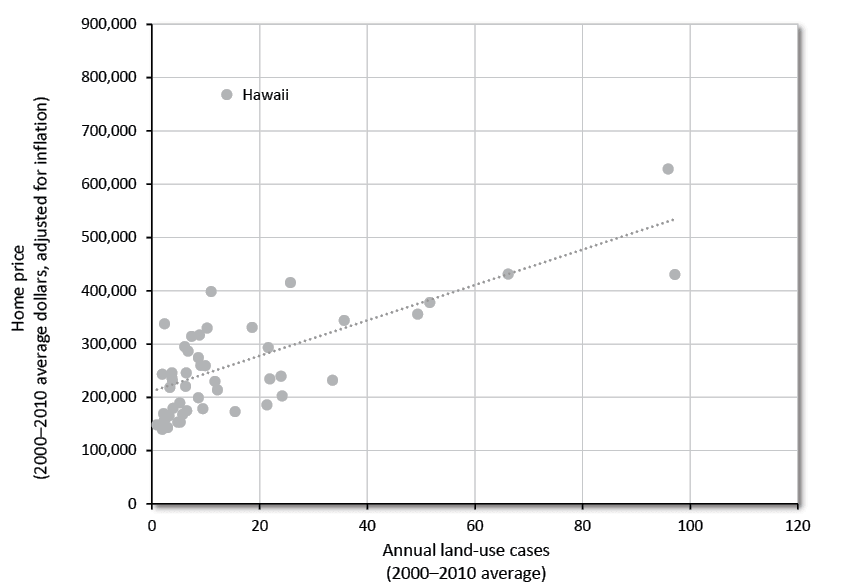

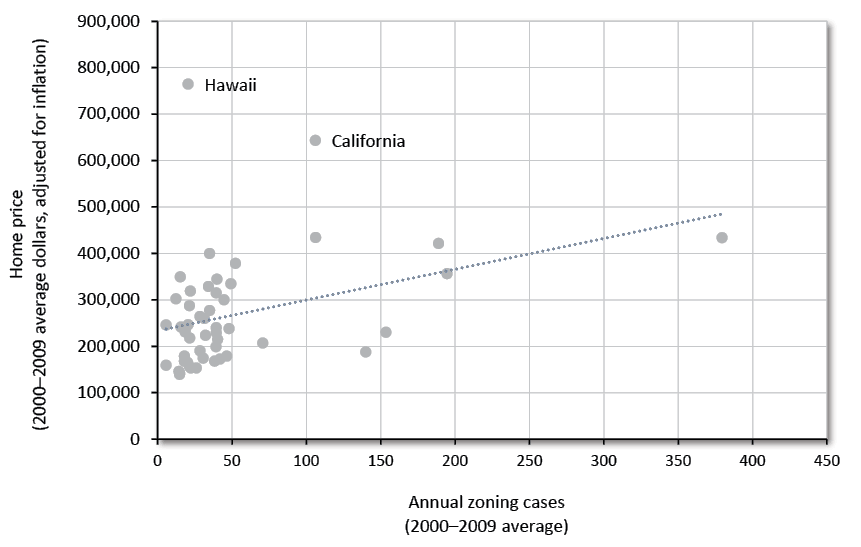

The trouble with rising regulation is that it creates barriers to new housing supply and thus often raises housing prices. Using the court case data, I examined the relationship between housing prices and land-use regulations across the states. I averaged the price and regulation data over a recent 10-year period—2000 to 2010—and performed a simple regression to estimate the strength of the relationship.

Figure 4 shows home prices are lower in states with fewer land-use regulations. The figure shows the fitted line from the regression, which is highly statistically significant.26 The states with the greatest volume of land-use regulations have the highest housing prices.

Separately, I examined this relationship for individual states. In 44 of 50 individual states, rising annual land-use regulation is associated with rising real average home prices over a 35-year period.27

Figure 4: Land-use regulation and home prices rise together: national (2000–2010)

Source Morris A. Davis and Jonathan Heathcote, “The Price and Quantity of Residential Land in the United States,”

Journal of Monetary Economics 54, no. 8 (2007): 2595–620. Case data was provided by Daniel Shoag of the Harvard Kennedy School; copy in author’s files.

Zoning regulation is also linked to home prices. Figure 5 shows home prices are lower in states with fewer zoning regulations. The figure shows the fitted line from the regression that estimates the relationship. The relationship is statistically significant.28 The states with the greatest volume of zoning regulations have higher housing prices, on average.

Overall, 36 of 50 individual states show rising zoning regulation is associated with rising home prices over a 35-year period.

Regulation is not the only factor responsible for changes in home prices. Geographic constraints, immigration, unemployment rates, consumer confidence, technological advances, marriage patterns, and location-specific amenities also affect the price of housing. Still, Figures 4 and 5 suggest that zoning and land-use regulations are important.

Figure 5: Zoning regulation and home prices rise together: national (2000–2009)

Source Morris A. Davis and Jonathan Heathcote, “The Price and Quantity of Residential Land in the United States,”

Journal of Monetary Economics 54, no. 8 (2007): 2595–620. Case data was provided by Daniel Shoag of the Harvard Kennedy School; copy in author’s files.

The relationship between regulation and home prices is important for public policy because regulation reduces housing affordability, and housing affordability is a major objective of a variety of federal, state, and local government programs.

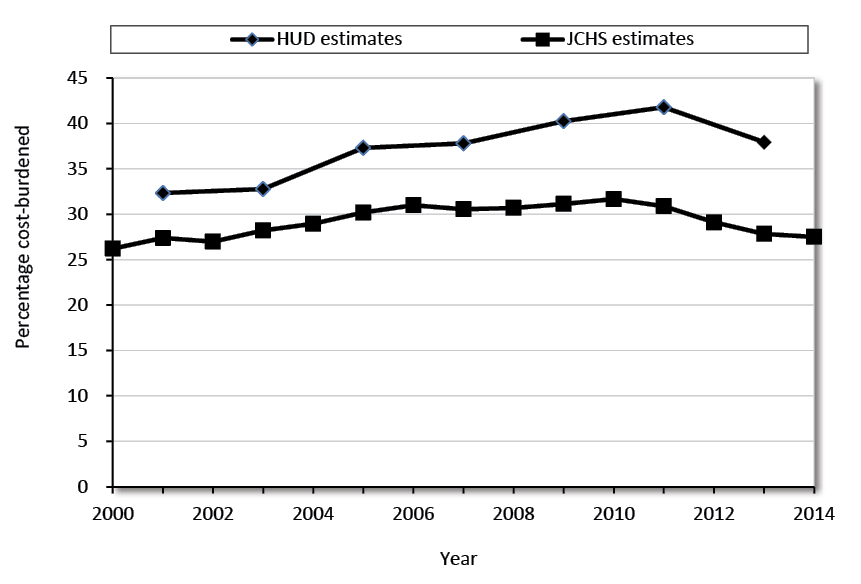

The federal government spent almost $200 billion to assist Americans in renting or buying homes in 2015.29 The Department of Housing and Urban Development spends about $50 billion per year, much of which is devoted to improving housing affordability. Despite this, the number of U.S. households that are considered “cost-burdened”30 by their housing has increased or remained constant over time (Figure 6).

Figure 6: U.S. share of cost-burdened households is not improving

Source “American Housing Survey of the United States—Complete Set of Tables and Standard Errors,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2001–2013,

https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs/data/2013/ahs-2013-summary-tables/national-summary-report-and-tables---ahs-2013.html. Joint Center for Housing Studies estimates are provided by Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. Copy of data in author’s files.

The outlook for severely cost-burdened households31 is not better. Aside from a small decline around the time of the financial crisis,32 the percentage of severely cost-burdened households has increased over time. In its most recent report, the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University projected that the percentage of severely cost-burdened households will increase 11 percent by 2025.33

Housing affordability advocates often attribute affordability problems to inadequate federal funding. But it is difficult to argue that inadequate federal funding is the source of affordability problems given the relationship between local regulation and housing costs.

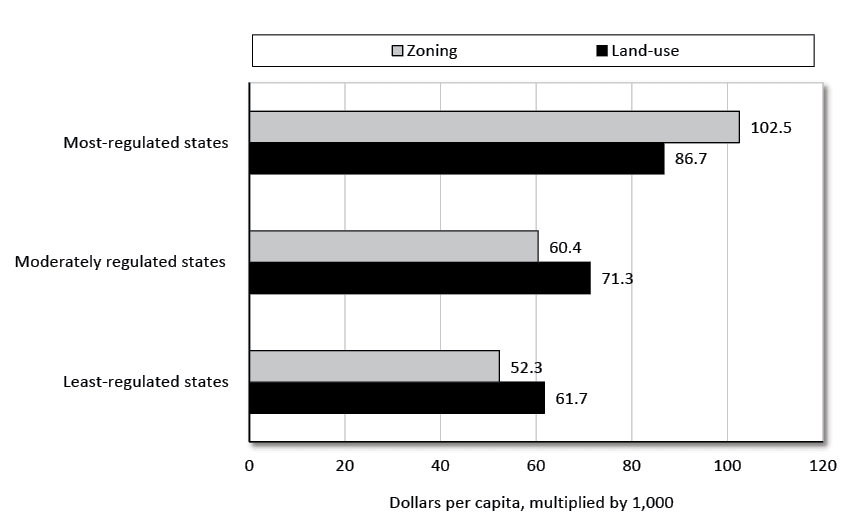

Regardless of whether federal funding improves affordability, federal money does encourage poor local policy decisions. After ranking the states based on the burden of their land-use regulations (Appendix B), I find that federal housing subsidies are concentrated in the most restrictively regulated states.

For example, federal housing voucher dollars go to the most-restrictively zoned states at more than twice the rate they go to the least-restrictively zoned states. And the most-restrictively zoned states receive nearly two times more federal dollars per capita compared to the least-restrictively zoned states (Figure 7). States seem to be rewarded for their counterproductive local policies. The relationship between federal subsidies and restrictive zoning regulations holds even after accounting for poverty.34

This arrangement poses some problems. First, it prevents states and local government from learning from their mistakes. When affordability problems arise, states can focus the blame on limited federal funding rather than reforming their local zoning or land-use policy.

Second, the relationship between federal and state government poses fairness issues. Federal taxpayers cannot reasonably be expected to subsidize the consequences of irresponsible state and local policies, but this is what happens under current federal policy.

Not all states ignore the cost of regulation; some states and cities have tried to mitigate its effects. They have tried inclusionary zoning, state affordable housing plans, luxury condominium taxes, developer linkage fees,35 and affordable housing quotas. At best, most initiatives only provide a Band-Aid solution, and at worst they undermine their claimed objectives. For instance, inclusionary zoning often weakens the economic incentives for new residential development, which is similar to zoning regulation. As a result, inclusionary zoning compounds housing supply shortages and leads to higher housing prices.36

Effective reform requires a direct approach. For example, states can reduce the scope of the State Zoning Enabling Act, which provides cities with broad latitude to regulate restrictively. States can also amend their laws to explicitly protect property owners from regulatory takings. Currently, property owners are rarely compensated for the destruction of property value accompanying zoning or re-zoning (e.g., re-categorizing property from multifamily residential to single-family residential).37

Figure 7: Federal housing affordability spending is highest in the most-regulated states

Source “2017 Budget State-By-State Tables,” Office of Management and Budget, 2017. This pairs the author’s 2015 state rank with 2015 budget numbers. Dollar values include Section 8 housing vouchers, Public Housing Operating Fund, and Public Housing Capital Fund spending.

If state government requires cities to compensate property owners for zoning or land-use regulations, this would deter cities from zoning or regulating arbitrarily. States can also reallocate housing subsidy dollars to cities that limit or reduce regulation. A handful of states, including Oregon, have tried this approach.

When major reform is out of reach, local governments can take small steps forward. Streamlining existing approval processes, and making certain classes of development by right—rather than discretionary—would increase housing supply and thereby improve affordability.

In the absence of regulatory reform, it is problematic for local government to rely on federal programs like Section 8 housing vouchers, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, and public housing to ease housing affordability issues. Reforming local regulation is both inexpensive and addresses the housing affordability problem directly.

As the academic literature and supporting analysis in this paper suggest, zoning and land-use regulations have deleterious effects on housing affordability. And zoning and land-use regulations are rapidly becoming more restrictive.

Unfortunately, local governments seem to be rewarded for counterproductive behavior. Current federal programs provide incentives for state and local government to ignore local contributions to the housing affordability crisis. Federal money cannot adequately compensate for the effect of local zoning and land-use regulations on housing affordability. Even if it could, using federal funds to back damaging local policy is irresponsible.

States and local municipalities can improve housing affordability without federal cash by reforming local zoning and land-use regulations. Reforms such as streamlining approval processes, making development by right, and reallocating state funds to cities reducing regulation provide benefits to all constituents. The benefits of reform include housing affordability, better job-to-worker matching, and improved economic growth.

Zoning and land-use regulations have different but overlapping meanings. Land-use regulation is an umbrella term that includes zoning as well as subdivision regulations; building codes; and national, state, or regional rules on land development and permitting (e.g., National Environmental Policy Act or California Environmental Quality Act). Zoning is an important subset of land-use regulation and includes land-use regulation associated with a city or county zoning ordinance. This report analyzes zoning and land-use regulation independently.

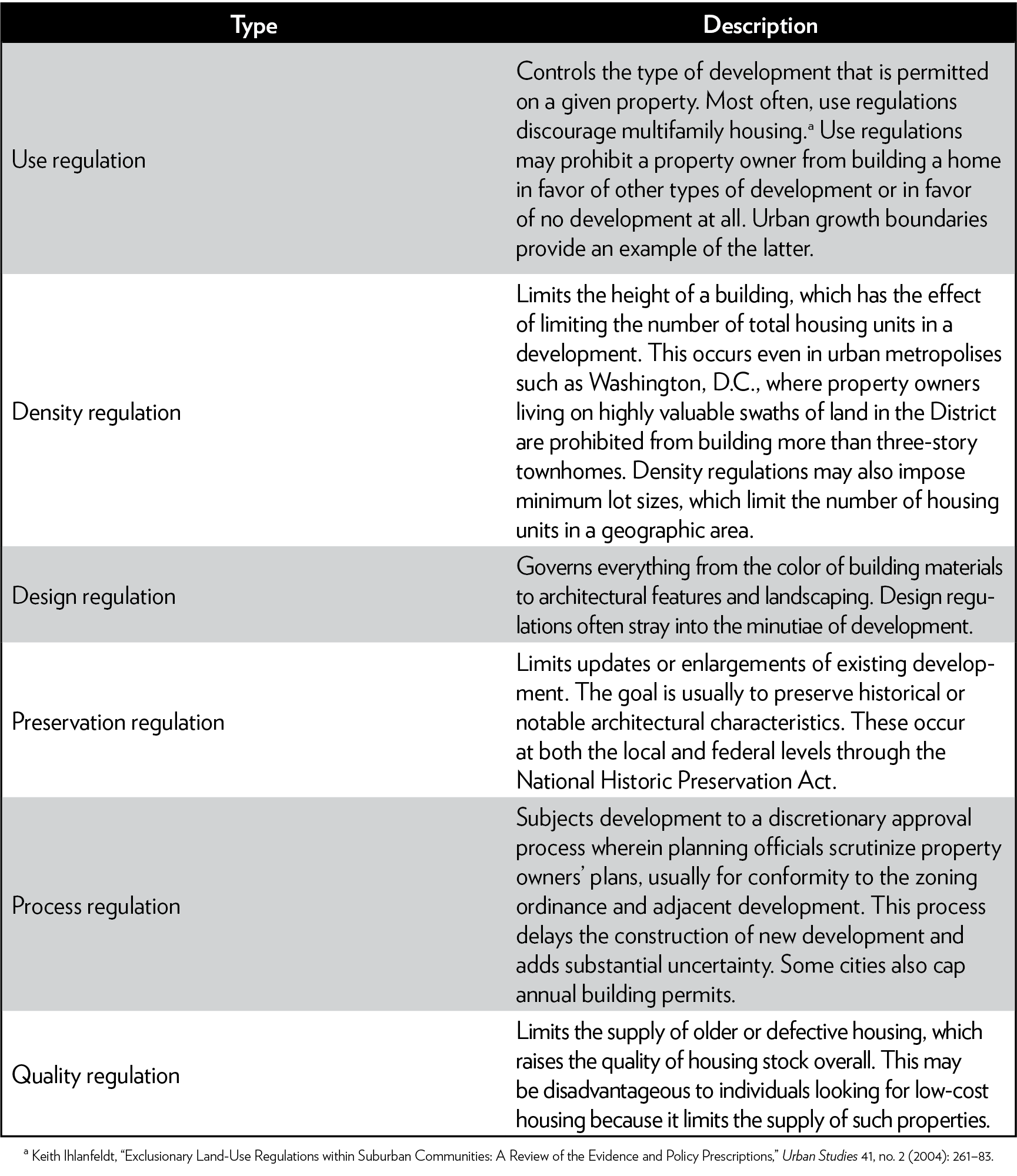

Together, zoning and/or land-use regulation affect the development of housing through some of the following important channels:

Table A.1: Types of zoning and/or land-use regulation

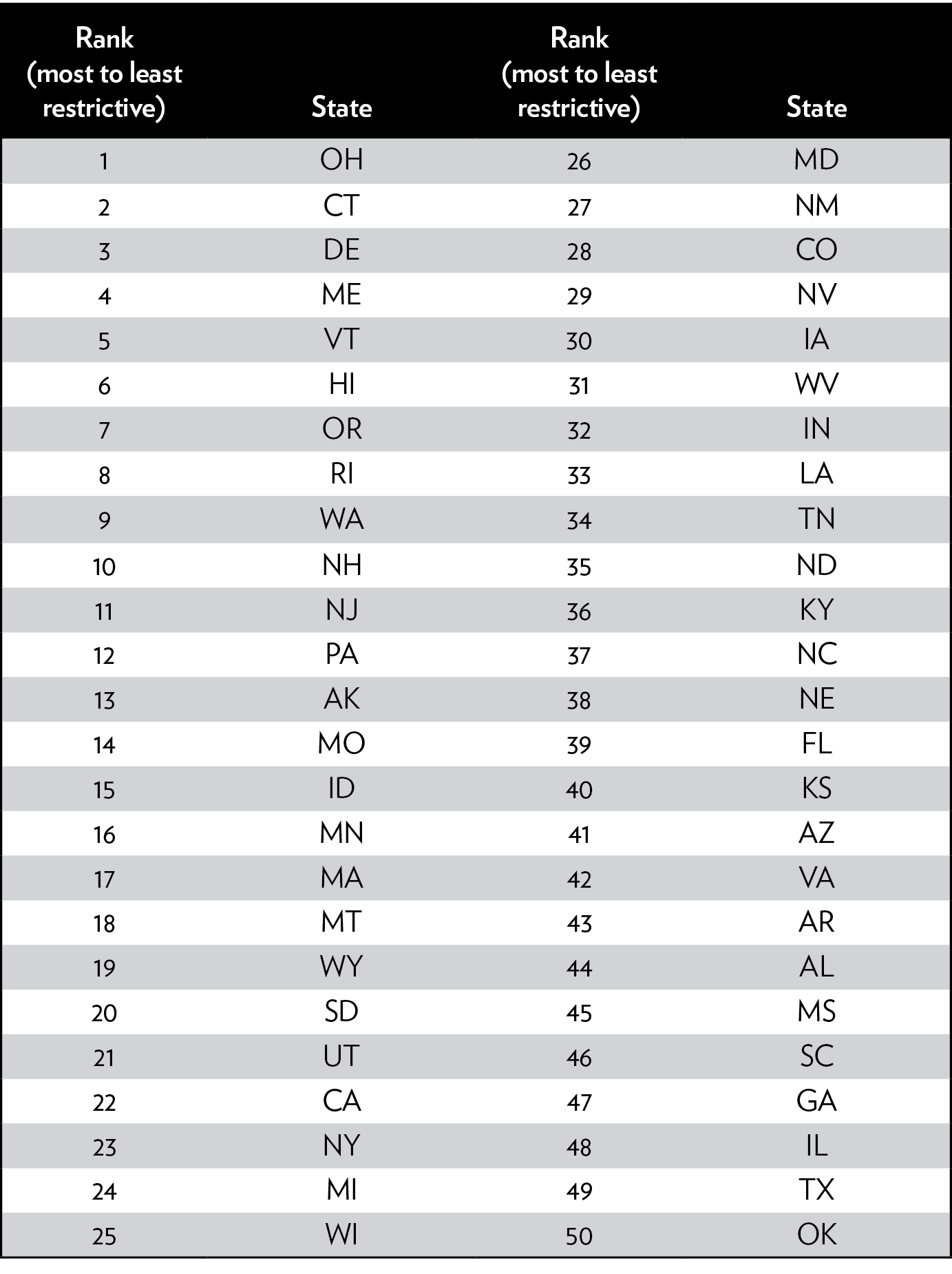

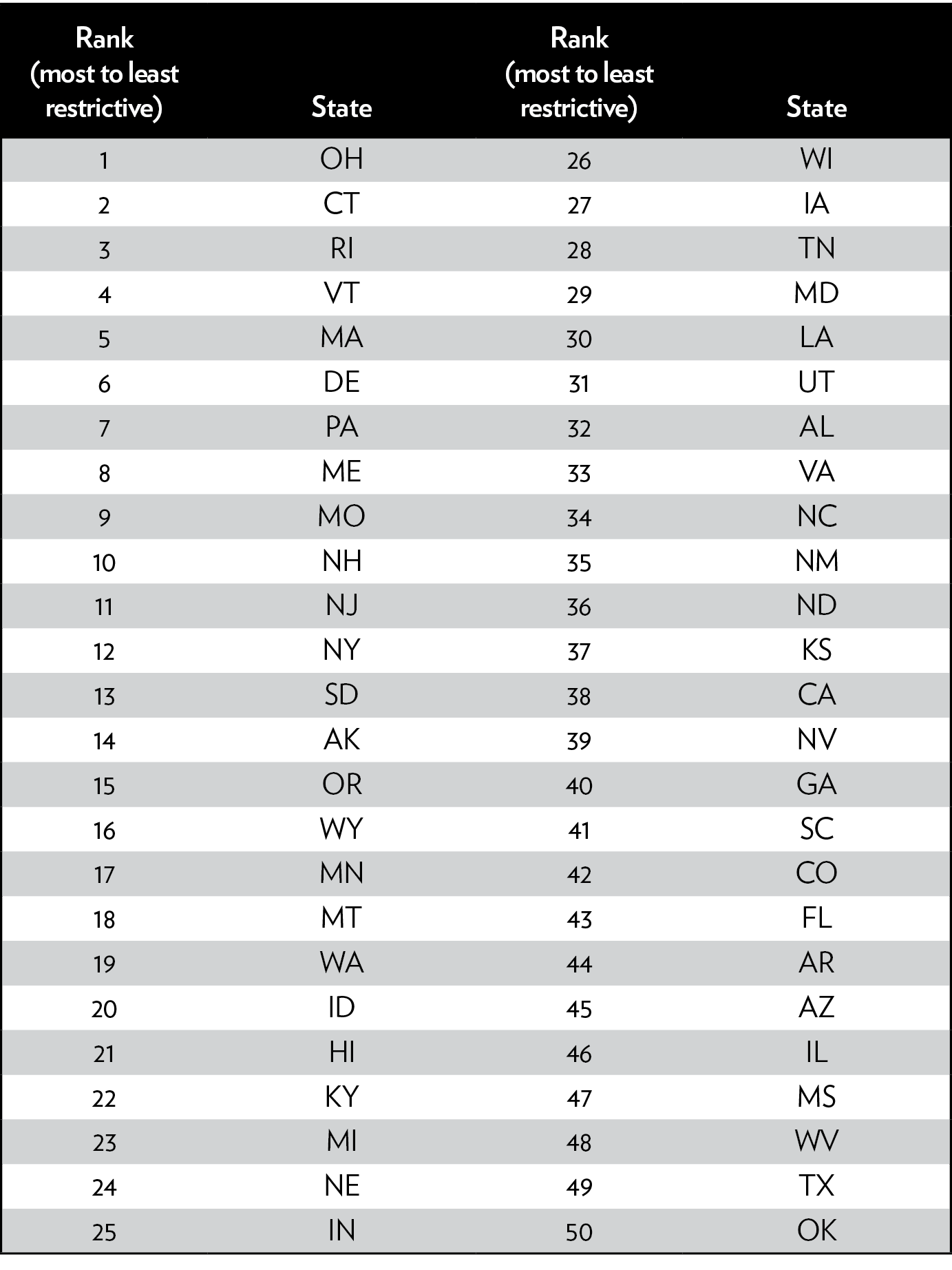

Regulation is trending up across states, and relative levels of regulation vary by state and geography. Tables B.1 and B.2 compare states’ relative level of regulation from 2000 to 2010, scaling by state population. The 2015 case and population numbers are used to conduct the federal spending analysis under Policy Implications.

Many of the states scoring high (low) on zoning regulation also score high (low) on land-use regulation.38 Southern states make up some of the least-restrictively regulated states. These states include Oklahoma, Texas, South Carolina, Mississippi, and Arkansas. Overall, southern states occupy 8 of the 10 least-restrictive spots for land-use regulation and 7 of the 10 least-restrictive spots for zoning.

Northeastern states make up some of the most restrictively regulated states. These states include Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, Delaware, Maine, and New Hampshire. Overall, northeastern states occupy 7 of the 10 most-restrictive spots for land-use regulation and 6 of the 10 most-restrictive spots for zoning. These results aren’t particularly surprising, given the northeastern states’ reputations for exclusionary zoning and the eastern states’ designation as some of the least-free states overall.39

Table B.1: State rank: land-use regulation

Table B.2: State rank: zoning regulation

Notes

- Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 21154, May 2015.

- See Appendix 1 for examples and descriptions.

- William A. Fischel, Zoning Rules! The Economics of Land Use Regulation (Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2015).

- Chris Edwards, “The Federal Emergency Management Agency: Floods, Failures, and Federalism,” Downsizing the Federal Government, December 1, 2014, https://www.downsizinggovernment.org/.

- Stewart Sterk, “Structural Obstacles to Settlement of Land Disputes,” Boston Law Review 91 (2011), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1581737.

- William A. Fischel, “An Economic History of Zoning and a Cure for Its Exclusionary Effects,” Urban Studies 41, no. 2 (2004): 317–40.

- Michael Tanner, Poverty: A Libertarian Perspective (Washington: Cato Institute, forthcoming).

- Fischel, “An Economic History of Zoning.”

- Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365 (1926).

- Previous research suggests that zoning regulation allows the conversion of property taxes into a user fee. See Fischel, Zoning Rules!

- Jonathan T. Rothwell, “The Effects of Density Regulation on Metropolitan Housing Markets,” working paper, the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, 2009, https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1154146.

- Jenny Schuetz, “No Renters in My Suburban Backyard: Land Use Regulation and Rental Housing,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 28, no. 2 (2009): 296–320.

- Edward L. Glaeser and Bryce A. Ward, “The Causes and Consequences of Land Use Regulation: Evidence from Greater Boston,” Journal of Urban Economics 65 (2008): 265–78, doi:10.3386/w12601.

- John M. Quigley and Steven Raphael, “Regulation and the High Cost of Housing in California,” American Economic Review 95, no. 2 (January 2005): 323–28.

- Keith Ihlanfeldt, “Exclusionary Land-Use Regulations within Suburban Communities: A Review of the Evidence and Policy Prescriptions,” Urban Studies 41, no. 2 (2004): 261–83.

- Edward Glaeser et al., “Why Is Manhattan So Expensive? Regulation and the Rise in House Prices,” Journal of Law and Economics 48, no. 2 (October 2005): 331–70.

- Salim Furth, “Costly Mistakes: How Bad Policies Raise the Cost of Living,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder no. 3081, November 23, 2015, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2015/11/costly-mistakes-how-bad-policies-raise-the-cost-of-living.

- Daniel Shoag and Peter Ganong, “Why Has Regional Income Convergence in the U.S. Declined?,” working paper, Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University, January 2015, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shoag/files/why_has_regional_income_convergence_in_the_us_declined_01.pdf.

- Jonathan T. Rothwell and Douglas S. Massey, “Density Zoning and Class Segregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Social Science Quarterly 51, no. 9 (December 2010):1223–43.

- Sanford Ikeda and Emily Washington, “How Land-Use Regulation Undermines Affordable Housing,” Mercatus Research, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, Virginia, November 2015, https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Ikeda-Land-Use-Regulation.pdf.

- Hsieh and Moretti, “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation.”

- The data set was provided by Daniel Shoag of the Harvard Kennedy School. The data contain annual land-use regulations and annual zoning regulations by state over a nearly 70-year period. See Appendix 1 for definitions.

- Land-use cases correlate well with other measures of land-use restrictiveness, according to Shoag and Ganong. Examples include the Wharton Residential Land Use Regulation Index and a survey of the American Institute of Planners. The former surveyed states’ local governments, courts, and executive branches on various process- and outcome-related aspects of land-use regulation; the latter surveyed planning officials about land-use policies in their states.

- Annual land-use cases vary from one year to the next, but the average number of cases rises over this period.

- Individual state analysis is provided in the associated online appendices for this paper, located at the following link: https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/documents/pa-823-appendix.xlsx.

- Details of the regression: R2 = 0.35, F-stat = 26, p-value = 0.00, t-statistic = 5.1. A fixed effects model using all 1,800 observations finds an overall R2 = 0.38, F-stat = 124, p-value = 0.01, t-statistic = 2.59.

- Oklahoma, Alaska, Oregon, Illinois, Missouri, and North Dakota are the exceptions to the rule. It is possible that certain states do not see a positive relationship between regulation and home price because regulation is relatively low.

- Details of the regression: R2 = 0.12, F-stat = 6.4, p-value = 0.01, t-statistic = 2.53. A fixed effects model using all 1,750 observations finds an overall R2 = 0.28, F-stat = 43, p-value = 0.08, t-statistic = 1.79.

- Will Fischer and Barbara Sard, “Chart Book: Federal Housing Supply Is Poorly Matched to Need,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/chart-book-federal-housing-spending-is-poorly-matched-to-need.

- Cost-burdened households spend 30 percent or more of their income on housing and housing-related costs.

- Severely cost-burdened households spend 50 percent or more of their income on housing.

- During the financial crisis, many homeowners saw home values fall.

- Marcia Fernald, ed., “The State of the Nation’s Housing 2016,” Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research/state_nations_housing.

- The author’s regression analysis uses her own state ranking and 2015 Office of Management and Budget numbers. Details of the zoning regression: R2 = 0.18, F-stat = 5.2, p-value = 0.00, t-statistic = 2.91. States with the most restrictive land-use regulation receive 40 percent more federal subsidies per capita than states with the least restrictive land-use regulation, but the relationship between the relative regulatory rank and federal subsidies is not statistically significant.

- Richard Epstein, “The Affordable Housing Crisis,” Defining Ideas, Hoover Institution,

February 27, 2017, http://www.hoover.org/research/affordable-housing-crisis.

- Ikeda and Washington, “How Land Use Regulation Undermines Affordable Housing.”

- Roger Pilon, “Property Rights and the Constitution,” in Cato Handbook for Policymakers, 8th ed. (Washington: Cato Institute, 2017), https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato-handbook-policymakers/2017/2/cato-handbook-for-policymakers-8th-edition.pdf.

- State rankings can be useful for describing general trends in regulation, but they have limits. California is a heterogeneous state, with lots of variation between coastal cities and the Central Valley. But California is toward the middle in land-use and zoning rank. This is because the state rank is an average, which means California as a whole looks better than many of its heavily regulated cities, such as San Francisco or San Jose.

- William Ruger and Jason Sorens, “Freedom in the 50 States: 2015–2016,” Cato Institute, https://www.freedominthe50states.org/.