Afghans have endured 40 years of uninterrupted war, and there is no plausible argument that war will soon end. In all the debate about troop surges or maintaining the status quo, two critical questions rarely get asked: Why have Afghans been at war for so long, and why can’t the United States and the international community end it? Some of the obvious answers include an incompetent Afghan government and security force, rebel sanctuaries in the mountains and in Pakistan, and the lucrative and illicit opium trade. Almost entirely ignored, however, is the role played by the decades of bone-jarring trauma experienced by Afghans.

Afghanistan has become a trauma state, stuck in a vicious cycle: war causes trauma, which drives more war, which in turn causes more trauma, and so on. Thanks to 40 years of uninterrupted war, Afghans suffer from extremely high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental illnesses, substance abuse, and diminished impulse control. Research shows that those negative effects make people more violent toward others. As a result, violence can become normalized as a legitimate means of problem solving and goal achievement, and that appears to have fueled Afghanistan’s endless war. Thus, Afghanistan will be difficult, if not impossible, to fix.

Trauma at this level imposes profound limits on America’s ability to effect enduring change in Afghanistan and other places. Accordingly, the United States should decrease its military footprint in the country and focus on efforts to incentivize a more effective and less corrupt Afghan government. More broadly, America should restrain its use of military force to those instances in which it is both effective and necessary, since sustained war in already traumatized states such as Afghanistan increases psychological damage and societal instability, making continued war more likely. Although it has become a common element of U.S. foreign policy, intervening with military force in another country’s civil war is almost never necessary to secure U.S. interests. When the United States does intervene, however, the population’s mental health status should be included in military planning and intelligence estimates as a relevant factor affecting the war and the likelihood of future stability.

Introduction

The central thesis of this analysis is that 40 years of war have fundamentally changed Afghans and made the country more prone to war in the future.1 A coup in 1978 ushered in a civil war followed immediately by the Soviet invasion. By the time the Soviet Union left in 1989, 7 percent to 9 percent of the Afghan population had been killed, with the death count rising to a staggering one in five for working-age males.2 Civil war resumed. Before the U.S. invasion in 2001, war in Afghanistan had already killed, wounded, or displaced half of the population.3 Then in late 2001, the United States invaded Afghanistan to destroy al Qaeda and dislodge the Taliban and later continued fighting to stabilize the country and establish a democratic government. As of 2018, Afghans remain mired in war, and the Taliban contest, influence, or control more territory than at any point since America initiated combat operations.4

U.S. efforts have been significant, yet American objectives remain largely unmet. Since October 2001, more than 2,000 Americans have been killed in Afghanistan at an estimated financial cost of $840 billion. Forty-one other countries have also contributed to the war in varying degrees.5

Seventeen years in, the United States remains torn between maintaining the status quo, surging military forces, or leaving the country altogether. The Trump administration has chosen to surge forces, but regardless of the path pursued, Americans can expect continued civil war involving the Taliban and other insurgent groups, as well as a corrupt, illiberal, and largely incompetent Afghan government. An end to the violence will happen only after one group finally monopolizes the use of force in Kabul and a sufficient number of provinces outside the capital, but even then there is a much higher than average probability that civil war will resume.

Unfortunately, neither the United States nor the international community can substantially improve Afghanistan’s situation. Instead, the future of the country rests primarily in the hands of Afghans who, to date, have largely been incapable of or uninterested in fundamentally changing conditions on the ground. A large number of policy analyses suggest otherwise: that a substantial and enduring U.S. presence will sufficiently improve the situation. However, those analyses typically ignore two critical questions: Why have Afghans been at war for so long? And why haven’t the United States and the international community ended the war after 16 years of trying?

The reasons for Afghanistan’s bleak future can be found in the answers to those two questions. Some of the more obvious explanations include the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces’ failure to stop the insurgency, the low opportunity cost of rebel recruitment, and insurgent sanctuary in the mountains and in Pakistan. Other likely causes include rebels motivated by grievances against their extremely corrupt government, as well as ethnolinguistic fractionalization between Pashtuns and others (e.g., Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Hazaras). Financial incentives likely motivate a number of insurgent groups too, as perpetual war perversely provides them an enduring income stream from the illicit opium trade that would otherwise be confined to traditional criminal elements if the conflict ended.

In addition to analyzing those areas, this policy analysis goes a step further and suggests an answer largely overlooked in the security studies literature — Afghanistan as trauma state. Simply put, Afghans have endured so much trauma that the society has fractured and now finds itself unable to function normally. Beyond Afghanistan, this analysis should inform future U.S. policies toward other states in the midst of civil war, such as Iraq, Syria, and Libya, which have histories of extreme trauma and are home to America’s current nemesis, Islamist-inspired terrorists.

This analysis begins with a brief review of the literature on the prevalence of civil war. Why are some countries, like Afghanistan, home to so much civil war while others never experience it? The next section provides a detailed answer to the more specific question, Why is there so much war in Afghanistan? The subsequent sections explore the reasons American and international efforts have failed to end the war in Afghanistan. The final section offers recommendations for U.S. efforts in Afghanistan now and for other high-trauma civil war states in the future.

Afghanistan’s Endless War

My experience in Khaki Khel in 2010 explains a lot.6 Our helicopters touched down just outside the village in this remote province in southern Afghanistan. The Afghan Army and police, along with an American military unit, had just conducted operations in and around the village, more to build confidence among the Afghan population than to kill or capture insurgents. At the conclusion of such operations, I would normally escort members of the Afghan government and medical community out to facilitate a dialogue between the government and their village constituents and to provide basic medical care. This time was different. The U.S. military unit made a mistake one evening when they fired off an illumination round. Instead of safely falling to earth after jettisoning its contents, the metal canister sliced through the bodies of two children asleep on the roof of their home to escape the summer heat inside. We had all come to pay our respects. Because of Afghan cultural considerations regarding gender roles, my female lieutenant’s mission for the day was to spend time with the grieving mother, apologize for the tragedy, and express our sympathies to her.

We made our way down the steep hill, away from the mud homes and into a field of poppies. A clearing opened up, and we took our seats to begin the shura (a traditional meeting of elders designed to share important information and potentially arrive at a consensus-based decision). The literacy rate varied between 1 percent and 10 percent in our province, but out here in such a remote place with no real access to a school or qualified teacher, probably less than 1 percent could read and write. They had no electricity, no cars, and no paved roads to connect them to other Afghans or business opportunities. As subsistence farmers, they lived harvest to harvest, and the droughts of the past few years had reduced crop yield and killed livestock. The gentle rebuke of other elders at an earlier time had taught me to never again say, “What a beautiful day” or, “Isn’t the weather nice?” These Afghans operated on a different step of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. For them, the weather was the difference between being able to feed your family or going hungry. The poppy field loomed in the background, both an economic incentive for the impoverished residents and a reminder of why the insurgents were interested in this remote village.

In accordance with custom, the village elders spoke first. They hit on two of the talking points that we would hear at virtually every shura: Why are you here when the insurgents are over there (said while pointing in the direction of neighboring Pakistan) and how do you expect us to stand up to the Taliban when you and 42 other countries can’t defeat them? The second point was so specific that we had long ago concluded that the insurgents had actually told it to them. The number would vary slightly from village to village, but it always stayed between 40 and 49. We concluded that the insurgents used the talking point to intimidate the villagers into submission, along the lines of: “Don’t bother resisting us. If the United States and 42 other countries with all of their weapons and technology can’t beat us, you shouldn’t think you can either.”

As the elders spoke in turn, one lost his composure and became very emotional in this public setting, something our training had suggested Pashtun men avoided at all costs. He implored the Afghan and American security forces to fight the Taliban “down here” in the field, not up among the villagers’ homes. He said it several times and in different ways. The message was clear: tell the Taliban to fight you down here, so innocent villagers won’t be caught in the crossfire. I turned to my interpreter, an Afghan man in his mid-20s who had my complete trust and admiration, and asked if he thought the elder was joking. “No,” he replied, “he is serious.” When my interpreter and I talked later, we concluded that the elder did not know the insurgents often intentionally put civilians in harm’s way as a means to achieve their goals. We also concluded that the elder truly believed the insurgents would fight us at the location of our choosing. Of course, from the insurgents’ perspective, their survival required them to never meet us at a time or place of our choosing.

Khaki Khel illuminates both of the primary arguments for the prevalence of civil war: the opportunity for rebellion and the motivation to rebel. The opportunity for rebellion typically exists when the state has ineffective or nonexistent security forces, when recruiting rebels is easy, and when rebels can readily find sanctuary. Grievances among the population and rebel groups’ desire to financially profit from illicit activities have typically fueled the motivation to rebel.7 Afghan security forces rarely operate in Khaki Khel, so for practical purposes the security forces do not exist. And even when combined with the U.S. military, Afghan forces were ineffective, having accidentally killed members of the very village they had come to protect. Additionally, with the villagers living harvest to harvest, low opportunity costs for rebel recruitment persisted. Even modest payments from insurgents go a long way for the average Khaki Khel family. As for the motivation to rebel, the villagers certainly have a number of grievances to choose from: an incompetent government that cannot even provide them with security, a corrupt government rated worse than 96 percent of all governments in the world, and a government that unwittingly kills their fellow villagers.8 Finally, the poppy field serves as a visible reminder of the perverse role financial incentives may play in fueling the rebellion.

But Khaki Khel made it clear that existing theories were incomplete. Something else important was going on. Evidence for a new theory emerged: a vicious cycle of war causing extreme trauma, and trauma, in turn, causing more war.

Afghanistan, the War State

Afghanistan’s 40 straight years of war provide ample support for both of the main theories of civil war and all of their subarguments. Data from those 40 years also support the argument that as war begets trauma, trauma also perpetuates war, and the vicious cycle continues.

Opportunity for Rebellion. The opportunity for rebellion has long been a feature of Afghan life. A strong federal government has proved elusive. The state security force has been largely nonexistent and, where present, highly ineffective. Rebels enjoy safe haven in the extensive mountains and in neighboring Pakistan, while Afghanistan’s enduring poverty reduces the costs of recruiting new rebels.

Ineffective or Nonexistent Security Forces. For the past century, Afghanistan has had an ineffective state security force, with the possible exception of 1953 to 1963 during Mohammed Daoud Khan’s tenure as prime minister.9 The country’s five civil wars during the 20th century speak to the enduring incompetence of Afghan security forces.10 Observers have characterized them as “almost useless,” “tactically inept,” “in disarray,” and able to conduct “only limited defensive operations.”11 Today, despite numbering more than 365,000, they barely control or influence half of the country’s districts.12 This incompetence, in part, motivated the Soviet Union to invade in 1979 and to try to prop up the communist regime in Kabul. Today, security force ineffectiveness keeps American advisers and trainers there after 16 years of trying to professionalize the Afghan force.

Incompetent Afghan security forces also make the villagers’ lives more difficult. At shuras I attended, the senior Afghan government leader presented gifts, paid for by American taxpayers, to each of the elders in attendance. At slightly more than half of those shuras, I watched the elders politely refuse the gifts. Initially, it seemed to make no sense. Even if the elders hated their government, why refuse a free prayer rug or Koran? Years earlier, Osama bin Laden had reminded his followers of the value of trying to financially bankrupt their enemies. Taking the gifts with no strings attached appeared to be a good, albeit small, way to get back at America.

At one shura, however, my confusion was cleared up: everything came with strings attached. As we made our way into the village, only one elder greeted us. The Afghan deputy governor expressed his disbelief, “Where are all of your white beards?” The elder said the others were out in the fields working, as he pointed up into the nearby hills.

The deputy governor did not believe him. He noted that the Afghan Army and the Americans had been out there for three days, and they had certainly told the elders we were coming today.

The back-and-forth went on for 15 minutes until the elder finally admitted that the others were hiding in a nearby compound for fear of what the insurgents would later do to them. He agreed to fetch the other elders and allow the shura to proceed. As the shura began, one of the elders drove the point home. He asked us and his government not to come out to his village anymore. He said that three years before, the Afghan government and a previous American unit had come to the village and given them supplies to clean their irrigation system. A few days later, after the government and the Americans left, the insurgents came and destroyed much of their kareze (a traditional communal irrigation system that relies on tunneling to tap existing groundwater) and abused their elders in front of everyone, accusing them of working with the infidel government and the Americans. Two years before that, he said, the government and the Americans came and dug the villagers a well. But after they left, the insurgents returned, destroyed the villagers’ well, and humiliated the elders in front of the people. The elder acknowledged that the previous year the government and the Americans had respected their wishes and did not come out. He said that the villagers had put their meager monies together and bought a small farming machine. Unfortunately, the insurgents assumed the Afghan government or the Americans had bought it for them, so they destroyed it and again punished the elders for cooperating with the infidels.

He made his point clear enough. The transitory presence of the Afghan security forces put the elders and villagers in greater peril than if the security forces had never come. In both scenarios, the Taliban largely controlled the lives of these Afghans, but in the second scenario the Afghans suffered less.

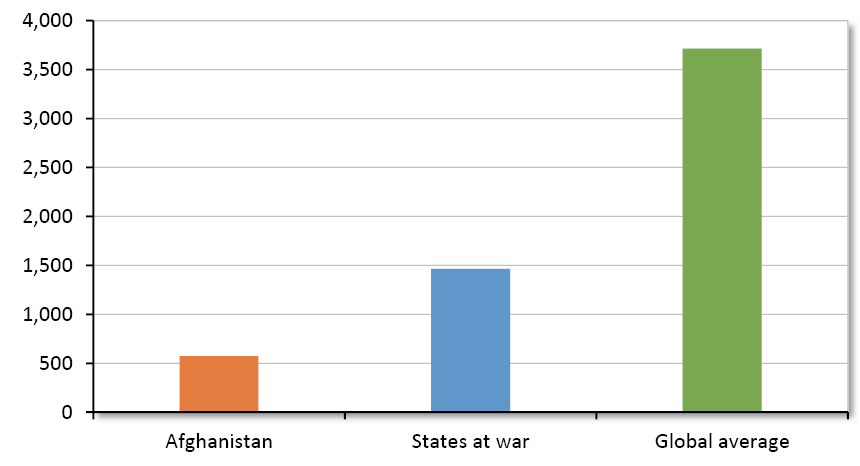

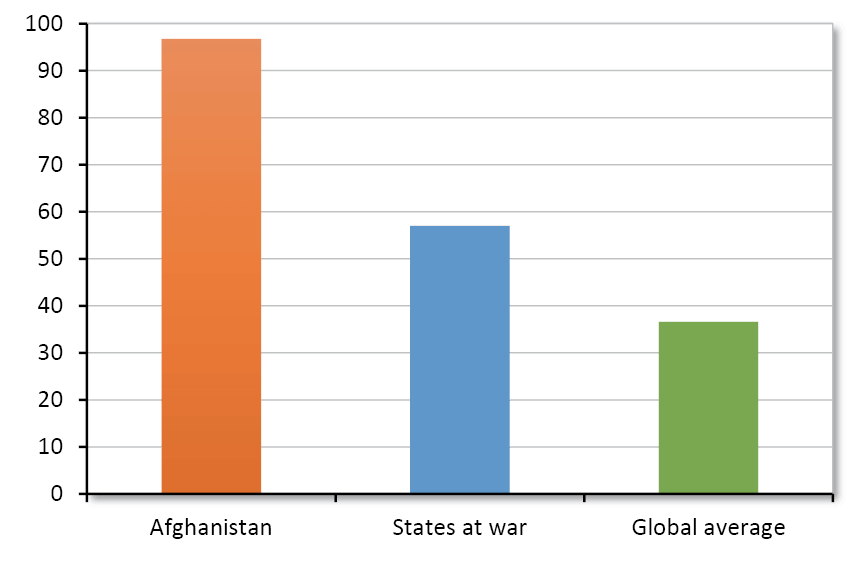

Low Opportunity Costs for Rebel Recruitment. Afghanistan has typically had low opportunity costs for rebel recruitment, and persistent war has only reduced them further. As Figure 1 shows, for the last 40 years of the 20th century, Afghanistan’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita averaged 40 percent of that of all states at war and one-sixth of the worldwide average.13 When America invaded in 2001, Afghans had an average annual income of $117.14 The Central Intelligence Agency’s 2017 World Factbook ranks Afghanistan 207th out of 230 for income per capita despite the billions poured in by the United States and other members of the international community.15 Afghanistan’s GDP per capita is 11 percent of the global average (and 2.8 percent of America’s). Comparatively, Afghanistan hit its high-water mark in 1950, when its GDP per capita reached 30 percent of the global average. Afghanistan’s GDP per capita has also grown at an inferior rate. Over the past 60 years, the worldwide average has grown 263 percent versus just 35 percent for Afghanistan.16

Figure 1: Gross domestic product per capita, 1960–1999 (in current U.S. dollars)

Afghans suffer from extremely high rates of illiteracy, and even after 16 years of effort from the international community the prospects for improvement remain bleak. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) estimates a 32 percent literacy rate for Afghans as of 2011, woefully below the global average of 85 percent.17 ONE, an international nongovernmental organization, currently rates Afghanistan the world’s fourth-worst country in education for girls.18 An uneducated workforce offers little hope for economic growth. Insurgency, therefore, remains an attractive source of income.

Two bright spots, however, emerged in Khaki Khel, where a meager 1 percent to 10 percent were literate. When we went on patrol, the children would gravitate to us with shouts of “Qalam, Mister. Qalam, Mister.” They wanted pens. Not money or food, but pens. My Afghan interpreter thought it indicated both an aspiration to be literate on the kids’ part and a desire to have something unique and prestigious. The young women in Alamat, our province’s capital city, represented the second bright spot. They wore their uniforms when walking to school, which made them a visible target for the insurgents. They could easily have put on burqas, but they chose to have everyone see them in their uniforms, a particularly bold step in the very conservative province.

Rare bright spots aside, decades of war have crushed Afghanistan’s economy and the human capital that would normally undergird it. GDP per capita has been set back, making insurgency a more lucrative source of income. However, the widespread trauma, the internally displaced persons and refugees, and the lack of education have severely affected Afghans’ capabilities over the long term.19 When countries remain at war for too long, waging war can become the citizens’ only marketable skill.20

Rebel Sanctuary. Insurgents have benefited from sanctuary in neighboring Pakistan.21 The Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium indicates that Taliban leaders have enjoyed safe haven in Pakistan since shortly after the United States initiated combat operations in Afghanistan back in 2001. The so-called Quetta Shura — named after the Pakistani city in which they enjoy refuge — even openly collects funds through various charity fronts in Quetta and other Pakistani cities.22 In 2009, President Barack Obama publicly called on Pakistan to “demonstrate its commitment to rooting out al Qaeda and the violent extremists within its borders.”23 President Trump recently repeated a similar refrain when he announced a surge of forces back into Afghanistan: “We can no longer be silent about Pakistan’s safe havens for terrorist organizations, the Taliban, and other groups that pose a threat to the region and beyond.”24 Presidential protestations aside, Pakistan has provided sanctuary to rebels for 16 years and counting.

Additionally, the Taliban, al Qaeda, and other insurgent groups have successfully sought refuge in Afghanistan’s mountains.25 Osama bin Laden, for example, hid in the Spin Ghar mountain range before escaping during the Battle of Tora Bora in late 2001.26 More recently, the Taliban occupied the same cave and tunnel complex only to be sent fleeing, ironically, by Islamic State fighters who then took up residence there.27 Territorial sanctuaries continue to enhance insurgent viability.

Motivation to Rebel. Grievances. “We don’t want any more of your mercy.” The elder spoke those words during a shura between his village and the Afghan provincial government in the summer of 2010. His comments seemed directed primarily to his government and, to a lesser extent, me and the other representatives of the U.S. military in attendance. As my interpreter translated, I could not help but think, “With friends like these, who needs enemies?” The elder’s turn of phrase, however, held no hint of humor, only years of pent-up pain and anguish. And he was basically right. Legitimate (and some illegitimate) grievances filled his life and the lives of the villagers he represented. His government remained mired in the worst levels of corruption and delivered no goods or services to his village: no roads, schools, or agricultural assistance and, worst of all, no security. Insurgents came and went at will, forcing villagers to provide them with food and other logistical needs, while humiliating and beating elders to compel compliance. Additionally, the insurgents, typically young men in their 20s, upended the Afghan cultural norm of respect and deference to the aged.

In addition to legitimate and enduring grievances against their government, water rights and ethnic fractionalization also fuel lasting resentments. The Asia Foundation’s annual survey of Afghan sentiments routinely shows water availability to be one of the top concerns at the local level.28 During my time there, frustrations over water access became evident in several ways. First, residents near a U.S. military base had lodged a complaint well before my arrival, a complaint that persisted after I had departed. They alleged that construction on the military base had unintentionally curtailed their water supply to almost nothing.

Second, elders petitioned us to install several wells in their village. My staff checked the records left by previous teams and noted that five wells had reportedly been dug in that village a few years earlier. When the team members shared that information with the elders, the elders fired back that one family and its extended members had monopolized those wells, leaving everyone else in the village to fend for themselves.

Ethnic fractionalization also provides fodder for enduring grievances. According to Barry Goodson, Middle East studies professor at the Army War College, absent the “preexisting ethnic tensions,” the civil war that began in 1978 would probably not have started so rapidly or spread so “vigorously.” Referring to the civil war that followed the Soviet departure, Goodson describes the “internecine fighting” among the different mujahideen groups. More broadly, Barnett Rubin of New York University notes the “powerful force” of ethnic division that pitted Pashtuns, Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Shiites against one another.29

Financial Incentives. Financial incentives also appear to fuel Afghanistan’s enduring war, with rebel groups using the conflict to shield their unlawful activities. The illicit opium trade incentivizes war, as insurgent groups profit from their illegal activity in the midst of instability more easily than they would if an established rule of law existed and the government enforced it. The United Nations reports that Afghanistan’s opium production increased 87 percent in 2017 from the previous year. The report goes on to note that poppy cultivation occurs on 328,000 hectares of the country — the most in the 24 years of available data and exponentially higher than the 8,000 hectares under cultivation when the United States invaded in 2001.30 For two decades now, opium has been the country’s “leading cash-generating economic activity,” accounting for an estimated one-third to one-half of total economic output.31

As noted by the U.S. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, the billions of U.S. and international community dollars flooding into the country have inadvertently introduced “perverse incentives.”32 The artificial and unsustainable increase in the size of the economy encourages Afghans to enter political life for corrupt purposes and further incentivizes them to keep the war going lest Americans and their money leave. Afghan government officials have siphoned off an estimated 20 percent of each contract, while the insurgents typically require a payment as well to prevent them from destroying the new project.33 The net result? More grievances against the government, increased viability for the insurgents, and more war.

Afghanistan, the Trauma State

The discussion so far is common to most civil wars. But to really understand Afghanistan’s case, policymakers should consider the role of trauma. Afghans have endured four consecutive decades of bone-jarring trauma that has changed them psychologically and physically. Those changes have ushered in harmful consequences not just for the traumatized individuals, but also for the population at large, which increase the likelihood that war will continue.

The American Psychiatric Association defines a traumatic stressor as any event that may “cause or threaten death, serious injury, or sexual violence to an individual, a close family member, or a close friend.”34 The severest traumatic stressors include torture, rape, and war. Increased rates of trauma are associated with psychological and physical changes to individuals, which often profoundly affect them and those around them. Exposure to traumatic stressors frequently results in mental disorders, especially post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (depression).35 Populations that have endured mass conflict, high rates of torture, and significant displacement similar to Afghans have a reported prevalence rate of between 17 percent and 50 percent for PTSD. That compares with a substantially lower estimated global rate of only 5 percent.36

Traumatic stressors also lead to physical changes. Exposure to trauma correlates with stunted growth in key brain areas.37 These changes include lowered hippocampal volume, decreased corpus callosum size, and diminished activity in the basal ganglia.38 Such physical changes often result in a lowered IQ, reduced impulse control, difficulty paying attention, memory impairment, diminished capacity to reason, inability to plan, and poor problem-solving skills.39

Finally, traumatic events have a more pernicious effect when the events occur during adolescence. Two generations have now come of age in the Afghan trauma state.

Afghans have been, and continue to be, exposed to an extraordinary number of traumatic events, both in severity and frequency. Studies indicate that, on average, Afghan adults have experienced 7 traumatic events, while children have endured between 5.7 and 6.6. Those events include being bombed or shelled during war, being physically beaten by members of armed groups, domestic abuse, forced displacement, and the death of a loved one.40 That compares with fewer than one to two events for European samples, one to three for U.S. adults, and an estimated 1.8 in a multicountry sample.41 With regard to specific traumatic events, approximately 52 percent of Afghans, for example, report having experienced some form of violent assault compared with just 4 percent who live in a developed European nation.42 These findings generally conform to the broader trauma literature that suggests conflict-affected poor countries are home to high rates of traumatic stressors and that more traumatic stressors result in increased rates of PTSD and depression.43

Trauma, Mental Illness, and Other Negative Outcomes. Mark, my young Afghan interpreter, and I had just finished another depressing meeting at the Afghan governor’s office.44 Various officials had taken turns mocking and swearing at one another, making bizarre claims, and arriving at exactly zero decisions. We were now walking the hundred yards back to our compound. Mark’s head hung down, typically a sign he was upset.

I asked him what he made of the meeting, wanting to hear his insights into what was really going on. He, better than anyone, could make sense of the dizzying complexities of Afghans interacting with one another. His reply caught me off-guard.

“We all have PTSD,” he said. “Don’t listen to me or any other Afghans. We don’t even know what we’re saying. All of this has made us crazy.”

I did not believe him. Mark always performed his duties superbly. Moreover, during the numerous rocket attacks we endured together and the constant threat of improvised explosive devices, he never displayed the slightest fear.

I also doubted that many Afghans had PTSD because of the training I had received before deploying. The lecturers and readings (incorrectly) dissuaded me from believing that PTSD could explain much, if anything, about Afghan behavior or the war. Deeply held religious beliefs, the power of the Pashtunwali honor code, and close families, we were told, largely inoculated Afghans from mental illness or any other undesirable outcome that could be caused by the acute trauma they had experienced.

I was wrong, and so were the readings and the training we received before going to Afghanistan. It turns out that study after study shows that significant numbers of Afghans do meet the criteria for PTSD, depression, and various anxiety disorders. Although on average only 5 percent of the world’s population will meet the criteria for PTSD at any point in their lives, an estimated 29 percent of Afghans meet the definition now. Studies suggest even higher depression rates of between 37 percent and 68 percent for Afghans.45 Virtually all of the studies conclude that the more traumatic events a person is exposed to, the more severe the follow-on negative consequences for that person — psychologically and physically. For example, children who experience five or more traumatic events have a 300 percent increased risk of mental illness (as mentioned, Afghan children have endured, on average, between 5.7 and 6.6).46

In their meta-analysis on trauma and mental health outcomes published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Zachary Steel (et al.) observed that populations with very high reported rates of torture had a 46 percent prevalence rate for PTSD and 50 percent for depression. When respondents also came from countries with substantial amounts of political violence and terror, as measured by the Political Terror Scale, the estimated rate of PTSD rose to 54 percent.47 Unfortunately, and as will be further outlined later, Afghanistan has met most of these criteria for the past 40 years.48

Making matters worse, Afghans have no real opportunity to receive professional care. Researchers have reported that Afghanistan’s mental health services are “nonexistent,” that there is an “acute shortage” of qualified providers, and that the general situation is one in which “chronic mental illness has been left unattended in Afghanistan for decades.”49

Increased exposure to traumatic stressors causes an increase in mental illness, substance abuse, and diminished impulse control.50 People meeting the criteria for a mental disorder are 2.7 times more likely to also meet the criteria for an alcohol or drug disorder, with substantially more succumbing to a drug disorder than to one involving alcohol.51 Although approximately 30 percent of those with mental illness will also be diagnosed with a substance abuse disorder at some point, the number rises to 50 percent for those with “severe” mental disorders.52 Experiencing traumatic stressors, particularly during childhood, decreases an individual’s impulse control.53 Chronic traumatization, like Afghanistan’s for the past 40 years, intensifies the effect.54 No surprise, then, that both PTSD and depression are associated with impulse control disorders.55

Trauma and Violence. Colonel Naseri began berating Colonel Habib in front of their subordinates and their American counterparts in the operations center. Habib, the number-two police officer for the province, had angered Naseri, the chief of the provincial security directorate, by arresting one of Naseri’s men. The arrest took place after an investigation into the serial raping of an Afghan boy. The Afghan National Police had wanted to arrest their prime suspect, but the suspect’s brother — an agent who worked for Naseri — kept using his position to keep the police at bay. Finally, word had made its way to Habib. Fed up, he had the suspect and his brother arrested for obstructing the investigation. Naseri fumed in response. An intellectual, he chose this moment to publicly mock the uneducated Habib, who had spent most of his life at war. We, the American forces, loved Habib. He was one of the few brave men who consistently took the fight to the enemy, and the drug addiction that we surmised he had was understandable in a land where self-medication was about the only option.

As the barrage came his way, Habib could do little to match Naseri’s verbal skills. Eventually, a switch flipped and Habib unholstered his handgun. There, in the Afghan equivalent of a war room, Habib aimed his weapon at Naseri. Fortunately, a nearby American officer rushed in between the two men and stood in front of the loaded firearm. Unable to communicate in Pashto, he spoke the only English Habib understood and accompanied it with hand gestures, “It’s OK, Habib. It’s OK.” Habib holstered his weapon. The next day, all of the government buildings had paper signs posted with a picture of a handgun surrounded by a red circle with a red line running through it: no guns allowed. The Afghan general in charge of the operations center also banned Habib from the premises for 30 days.

The mental health literature indicates that people with mental illness, substance abuse issues, and diminished impulse control commit more acts of violence against others, all else being equal.56 Studies suggest that Afghans suffer from atypically high rates of all three. By themselves, those factors would predict that Afghanistan should be home to higher rates of violence than other countries.

Mental health experts characterize the Afghan population as being “greatly affected by psychological distress.”57 The United Nations notes the “widespread” use of opium within the country and a problem-drug-use rate twice the global average and climbing.58

Afghans also experience (and mete out) extremely high rates of domestic violence.59 International and national human rights organizations, such as the UN, Amnesty International, and the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, assess the problem of physical abuse of Afghan women as “desperate.”60 Global Rights described the violence as “so prevalent and so pervasive that practically every Afghan woman will experience it in her lifetime.”61

Likewise, academics have characterized the violence as “pervasive and socially tolerated.”62 In a study of more than 4,000 women currently living within the country, 39 percent responded that their husbands had hit them within the past year. Eighty-seven percent reported they experienced at least one form of physical, sexual, or psychological violence, and a substantial majority said they had experienced multiple forms of violence.63 Nearly a quarter of the time, women identified their mother-in-law as the primary abuser. Domestic violence has become so normalized that “many women noted satisfactory marital relationships while simultaneously reporting experiences of violence in the home.”64 By comparison, global estimates of lifetime physical abuse rates by an intimate partner range from 10 percent to 50 percent.65

Research on Afghan children indicates that 35 percent have experienced physical violence in the past month at home, and 77 percent have experienced or observed at least one lifetime episode of violence in the home. The children, aged 7 to 15, reported an average of 4.3 lifetime violent episodes within the home. Nearly a third reported witnessing their fathers beat their mothers, and 60 percent said their mothers had beaten them (vs. 42 percent who reported their fathers had beaten them).66

During my time in Afghanistan in 2010, nonwar violence occurred frequently and in ways that seemed excessive. One of the district chiefs — similar to a U.S. mayor — dispatched his bodyguard to establish an illegal checkpoint and shake down motorists, particularly those transporting goods for sale. The practice of illegal checkpoints was common enough that businessmen had created workarounds. In this instance, the entrepreneur had illegally hired Afghan National Police officers to guard his convoy of wares en route to Pakistan. As the loaded trucks rumbled up to the illegal checkpoint, the district chief’s bodyguard and cronies motioned for the convoy to stop. It did not. The bodyguard brandished his weapon, and the police officers responded by making it clear they were police. A firefight erupted.

Police officers assaulted one another. Even senior-ranking officials would occasionally strike their peers during arguments. At a shura, I watched as the district chief publicly smacked a police officer with all his might. The incident occurred as final preparations were being made just before the start of the meeting. Neither my interpreter nor I could determine a particular reason for the physical violence beyond the stress often associated with putting on large events attended by dignitaries. In 50 years, I have never seen that behavior in America, but within a year I saw it in Afghanistan.

The “green-on-blue” attacks — as incidents in which Afghan forces attack U.S.-led coalition forces came to be called — offer another potential example of the connection between trauma and violence. Those events, in which an Afghan security force member attempts to kill his American or coalition counterpart, began occurring more frequently in 2011 when 35 coalition forces were killed and 34 wounded over the course of 16 incidents.67 The U.S. government estimated that 40 percent of the incidents resulted from “stress of various kinds,” while the Taliban, disguised as Afghan security forces, committed only 10 percent of the attacks.68 In 2012, the commander of the International Security Assistance Force (and senior coalition military officer in the country) concluded that the majority of attacks stemmed from “disagreements and animosities” and “personal grievance, social difficulties.”69 Insurgent infiltration, impersonation, and coercion accounted for only 25 percent of the attacks.70 In response, military leaders implemented a “guardian angel” program, requiring an armed coalition member to protect other coalition forces any time they interact with their Afghan counterparts (e.g., advising, assisting, and training them).71 The guardian angel program continues as of this writing.72

This perfect storm has likely made Afghans more violent and has helped legitimize violence as an acceptable option for problem solving and goal achievement in daily life. Ever-present domestic violence within the home and the war that permeates the entire society should therefore come as no surprise.

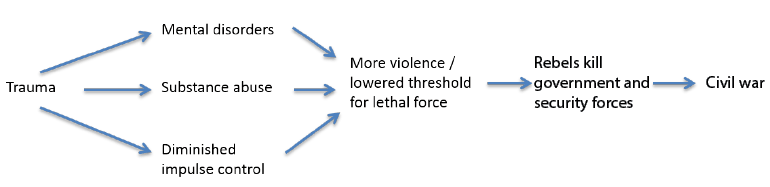

Trauma and Rebellion. Trauma’s effects on individuals and societies help explain civil war prevalence by providing an explanation for why some populations willingly resort to violence against their government while others do not. The civil war literature treats the threshold separating motivated citizens who will not employ lethal force against their government from those who will as a constant, despite, for instance, the obvious variation in violence rates across countries not at war. Research also indicates that the willful taking of human life is rare, even among military members. As a result, militaries provide substantial training to their recruits to ensure that they will actually kill in combat.73 Trauma’s aggravating effect on violence norms may be a cause of civil war: as a population’s exposure to trauma increases, the risk of civil war also increases. Figure 2 diagrams the potential effect of trauma.

Figure 2 : Trauma and civil war: Hurt people hurt people

Trauma can increase in three ways. First, traumatic stressors can become more severe. Victims of deliberate attacks, for instance, tend to suffer more symptoms than survivors of natural disasters. The severest traumas include torture, rape, and war. Second, the amount of trauma may increase over time. Third, the victim does not have time to heal. The trauma either continues or is relieved by only short intervals before the next traumatic exposure.74

An additional personal anecdote serves to illustrate the normality of torture and political violence in Afghanistan. One morning as Mark and I arrived at the provincial governor’s compound to attend a staff meeting, we saw the deputy governor standing outside on the patio waiting for us. After responding to my greeting in my limited Pashto, the deputy governor directed his comments to my interpreter. He asked if I had heard about the young girl and her father who had died at Checkpoint 7. I said no and asked for some details. The deputy governor said the child and her father had been caught between the Taliban and the Afghan National Police. The Taliban ambushed the police checkpoint, and during the gun battle both father and daughter had been wounded. After the fighting had died down, the police commander refused to let any villagers into the area.

“During the night,” the deputy governor said, “she was rolling around in a small space like this.” He held his hands apart as Mark translated his words.

I could not miss the horror suggested by his literal translation. The child spent her final hours writhing in pain alongside her father, who could not save her, as the two slowly bled to death.

The deputy governor went on to confirm that the Afghan National Police commander did not help the child and her father and would not let the villagers help them either. He said the police commander reported it might be a Taliban trap and that the area remained unsafe, but he readily conceded that the police officer had lied.

The deputy governor reckoned that the police officer wanted to send the people a message: if you let the Taliban stage an attack from your village, expect no help from us. So he gave them no help, and they died. The deputy governor concluded by saying that the officer had been jailed but would be released in a few days and then reassigned to the headquarters.75

People with mental illness, substance abuse issues, or diminished impulse control behave, on average, more violently than individuals without those conditions, and the highest risk for violence comes from individuals with both mental and substance abuse disorders.76 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders includes a chapter on disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders that involve “problems in the self-control of emotions and behaviors.”77 The negative effects of these disorders include behaviors that “violate the rights of others (e.g., aggression, destruction of property) and/or that bring the individual into significant conflict with societal norms or authority figures.” Experiencing traumatic stressors such as neighborhood violence, physical or sexual abuse, and harsh or neglectful parenting increases the probability of having one of these disorders.78

To put this in context, most individuals will not kill their fellow human beings. Writing on the logic of violence within civil war, Oxford’s Stathis Kalyvas observes, “Most are repelled by the prospect of acting violently, and so they will not.”79 Dave Grossman, a psychology professor and Army Ranger, notes that even military personnel go out of their way to avoid killing while in combat, driving the U.S. military to implement significant training efforts to ensure that they do kill.80

Current explanations for civil war typically treat this high threshold for deadly force as a constant. This is noteworthy because norms for measures of violence, such as gun violence and murder rates, vary dramatically across countries. The International Homicide Statistics database from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, for instance, shows the United States with a homicide rate four to eight times greater than similar countries (e.g., Canada, Australia, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom).81

Explaining societal violence after civil conflict has ended, Chrissie Steenkamp, a peacebuilding scholar, refers to a “culture of violence” in which society adopts “the norms and values that underpin the sustained use of violence.” Countries with high rates of trauma can eradicate previous norms and values and usher in new ones that “sustain the use of violence.”82 Political scientists Roos Haer and Tobias Bohmelt advance a similar argument for child soldiers, emphasizing the effects of trauma and the influence of learning by observation and imitation during war. In such cases, violence becomes normalized as a technique to solve problems and achieve goals in the postwar environment.83

The trauma argument provides insight into why some populations are more violent than others and how this occurs (i.e., by lowering the lethal-force threshold). A traumatized society will become more violent than a nontraumatized one, all else being equal. Likewise, an equal amount of grievance or greed in a traumatized society should cause more civil war than would occur in a society without severe prior trauma.

Measuring Afghanistan’s Trauma. To assess the potential impact of trauma, it is important to measure it. Afghans have endured a sickening number of the severest traumatic events such as torture, rape, and war over the past 40 years. In all measures, they not only have suffered more trauma than the average global citizen but also have been afflicted at even higher rates than those confronting other countries at war. (Most measures have been normalized and presented in a 0-to-100 format to allow comparison across the different trauma measures. See the appendix for more information.)

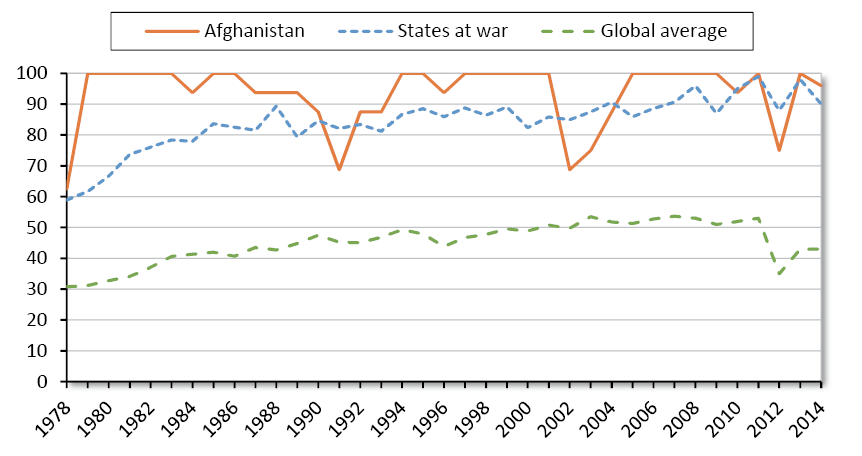

Torture. Afghans have suffered extremely high rates of torture for the past 40 years (Figure 3).84 The CIRI Human Rights Data Project (named for head researchers David L. Cingranelli and David L. Richards) made an assessment that the government “frequently” tortures its citizens — the highest possible rating — each year almost without exception.85 The data cover 1981 through 2011. Over that period, Afghanistan received the worst score 23 times, the middle score twice, and no score for six years because of government collapse or foreign occupation.86 In the history of the CIRI Human Rights Data Project, Afghanistan has never received the lowest (best) possible torture score.

Figure 3: Amount of torture, 1978–2014

Note: For more information on how the scores were derived, see the appendix.

The Political Terror Scale corroborates the CIRI data. The scale measures the amount of political terror by country from 1976 to 2016. Political terror is defined as “violations of basic human rights to the physical integrity of the person by agents of the state within the territorial boundaries of the state in question,” and the scale includes torture as an example of the violations governments can commit.87 Scores range from 1 to 5, with 1 defined, in part, as “torture is rare or exceptional” and 5 as “the terrors of Level 4 have been extended to the whole population.”88 Afghanistan has averaged a score of 4.6 over the 40 years. To put this into perspective, a score of 4 indicates “torture [is] a common part of life” and a score of 5 suggests terror affects the whole population.89

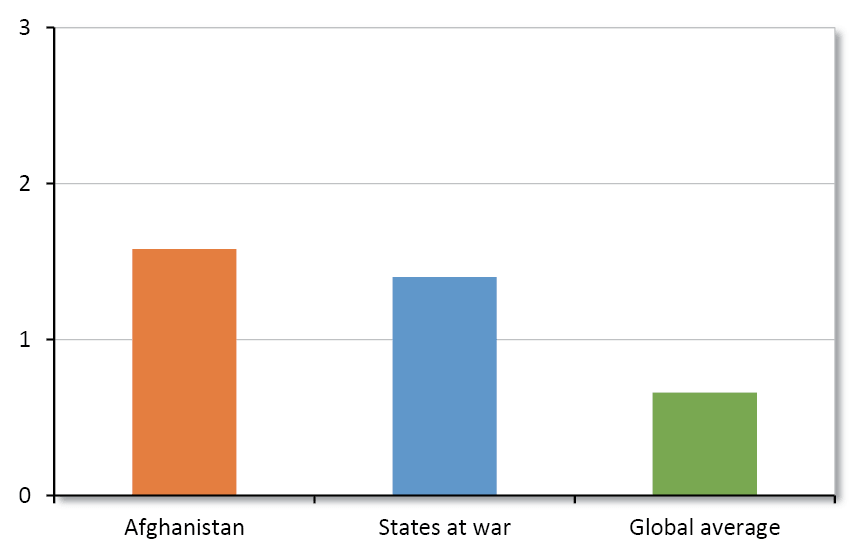

Rape. Of all traumatic stressors, rape has the highest conditional rate for PTSD. Nearly half of women and two-thirds of men who have been raped will, at some later point, meet the criteria for the disorder.90 The number of rapes that a population experiences typically increases during times of war.91 Having been at war for so long, Afghanistan will presumably have higher rates of rape than if the country had enjoyed peace during the same period.

In its 1995 report on Afghanistan, Amnesty International found that all warring factions “committed rape and other forms of torture,” particularly of women and children. The report also stated that women and girls throughout the country “live in constant fear of being raped by armed guards.”92 An interpreter I worked with, an Afghan man who lived in Kabul during the 1990s, described events that matched Amnesty International’s assessment. He said that when battle lines shifted too quickly, families did not have enough time to flee. He recalled watching in horror as several of his schoolgirl friends committed suicide to avoid being raped.

Some surveys indicate very low rates of rape in Afghanistan.93 The low reporting, however, is likely a response to strong cultural taboos rather than an accurate estimate of the situation. For example, some scholars have excluded survey questions that explicitly ask about sexual violence to avoid gathering inaccurate data. Instead, they use less detailed wording or ask questions that deemphasize the sexual aspects and instead focus more broadly on the violence.94

As Figure 4 shows, more rapes occur in Afghanistan than in the average country that experiences war, and substantially more occur in Afghanistan than the global average. Afghanistan’s score suggests rape is more than “a problem” but not “widespread.” (See the appendix for more information on this measure.)

Figure 4: Amount of rape, 1990–2014

War. As the following exchange in 2010 between a young captain on my team, an Afghan district governor, and a village elder conveys, the war has clouded people’s thinking and made them less predictable.

The elder shared his frustrations with both his government and the American forces: “We cannot come closer to you. We have no security. The Afghan forces and ISAF [International Security Assistance Force] come occasionally and only stay for a short time. When they leave, the Taliban come in and hurt us because they think we are cooperating with you,” he explained.

The American captain asked if the elder would be interested in overseeing a local self-defense force comprising men from his village. They would be armed to protect themselves and the other villagers and paid for providing security. The elder called the proposal ridiculous and said the Taliban would kill him and all his men. The captain gently probed the elder’s assumptions. He asked how many Taliban come into the village at a time. Ten to 20, the elder responded. He then inquired about the number of village men the elder could arm. Two hundred and fifty, the elder replied.

The captain asked the elder why he believed that the men from his village could not be armed to protect themselves and their village. The elder simply replied, “Because the Taliban will kill us.”95

The elder’s fear of the Taliban stemmed, in part, from the fact that neither his government nor the ISAF provided sufficient security for those in his village. His villagers were not alone. I estimated that 80 percent of the population in our province had no reasonable assurance of security on a round-the-clock basis. Instead, they lived in the midst of war. One day the Americans could bring out members of the Afghan government or security forces and the next day the Taliban might ride into the village. Security did not exist in any meaningful way, and from the villagers’ perspective uncertainty remained a constant.

The following three figures depict different ways to measure the amount of war trauma. Each figure compares Afghanistan with the average experienced by countries that had a war during any portion of the past 40 years and the average for all states in the international system. The different measures acknowledge that all wars are not created equal, with trauma levels varying substantially across them. Although Afghanistan has been at war for each of the past 40 years, the average length of time that other countries were at war during that period was a much briefer 11.8 years.

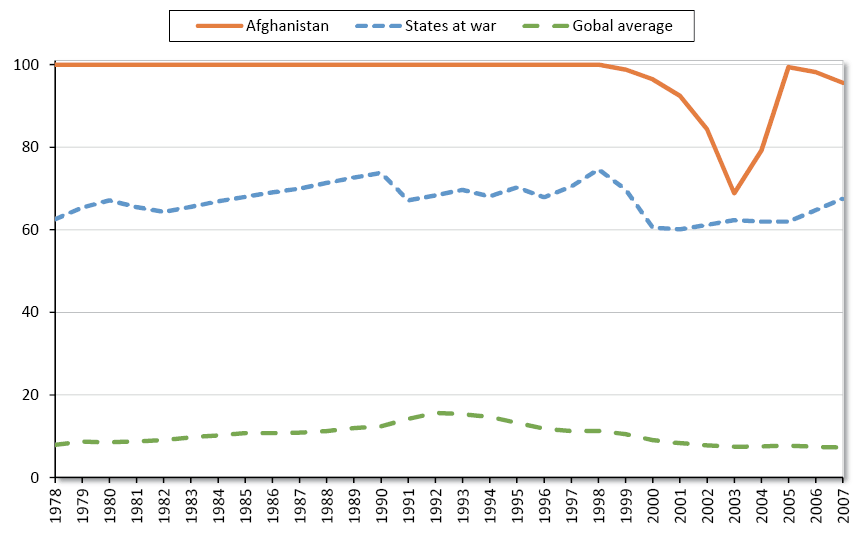

The war in Afghanistan directly affects more of the country than a typical war does, and it has done so consistently over time. As Figure 5 indicates, in each of the 30 years for which data are available, the war in Afghanistan affected more of the country than the average for all states at war. Whereas Afghanistan tends to receive the highest rating for virtually all years (i.e., the war affects more than half of the country), for the average war state only a quarter of the country is affected.

Figure 5: Amount of war (area magnitude), 1978–2007

Note: For more information on how the scores were derived, see the appendix.

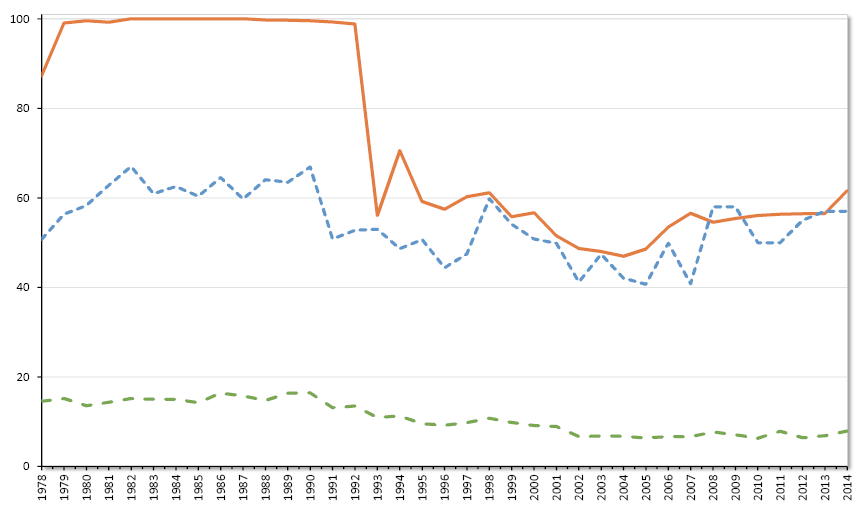

Afghans have also suffered more war fatalities per capita than the average war state in each year for which data are available (Figure 6). Throughout the Soviet occupation and civil war that followed, Afghanistan received the maximum score possible. Only when the Taliban took power did battle deaths decline a bit, and they have remained near this level ever since (except for the first few years after the U.S. invasion, when they temporarily declined even further).

Figure 6: Amount of war (battle deaths), 1978–2014

Note: For more information on how the scores were derived, see the appendix.

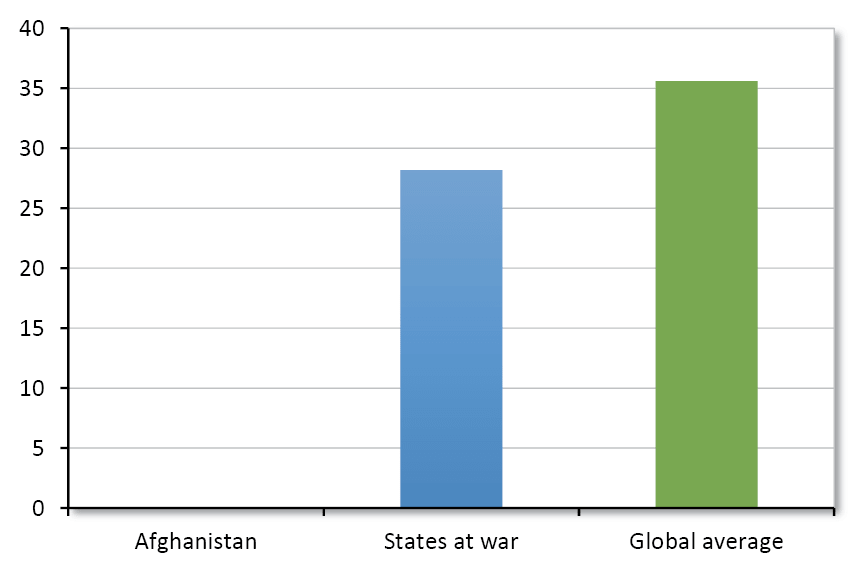

Time helps heal all wounds, as mental health professionals well know.96 Afghans, though, have endured 40 years of war trauma without any years of peace during which healing could begin. In contrast, the average country that experienced war has benefited from 28 years of peace during that same period (Figure 7). For the populations in those states, some degree of healing could take place during the periods of peace that elude Afghans. And, as expected, the average country in the international system has overwhelmingly enjoyed periods of peace rather than war.

Figure 7: Amount of war (years of peace), 1978–2017

Natural Disasters. Adding insult to injury, Afghans have even suffered more natural disasters than the populations of most other countries (Figure 8). Between 1978 and 2014, Afghanistan averaged a disaster score 20 percent higher than the average for all states that experienced a war at some point during that period. Interestingly, both Afghanistan and the broader group of war states had substantially higher proportions of their populations directly affected by disasters compared with the global average. Afghanistan’s average score is 84 percent higher than the global average, and the average score of war states overall is 53 percent higher. Since 1978, for example, disasters have left 42 percent of the Afghan population in need of “immediate assistance” compared with just 10 percent of Americans.97

Figure 8: Amount of natural disasters, 1978–2014

Note: For more information on how the scores were derived, see the appendix.

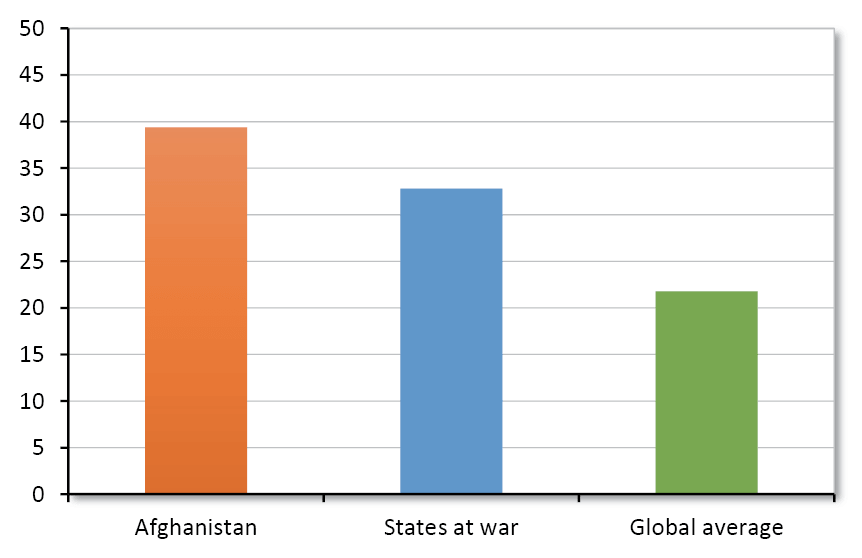

Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons. Afghanistan has suffered horrific rates of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). In 1990, for instance, more than half of the population qualified as refugees or IDPs. And in 7 of the past 40 years, more than 40 percent of Afghans found themselves fleeing for their lives. On average, one-fifth of the population have been refugees or IDPs every year since 1978. As with virtually every previous trauma measure, Afghans again rank first. Their average country score is 40 percentage points higher than the average for all countries that had a war and 60 percentage points higher than the global average (Figure 9).98 No wonder, then, that Larry Goodson, professor at the U.S. Army War College, referred to the Afghan refugee population as the “largest in the world,” and Louis Dupree, an authority on Afghanistan, called the massive dislocation “migratory genocide.”99

Figure 9: Levels of refugees and internally displaced persons, 1978–2014

Note: Refugee and IDP numbers were converted into a per capita proportion for each country-year. The data were then normalized via z-score and finally transformed into a percentage from zero to 100.

Note: For more information on how the scores were derived, see the appendix.

For the past 40 years, Afghans have suffered trauma rates beyond those of other countries at war. Even worse, they endured that trauma without interruption, while the populations of the average war state faced high levels for only a fraction of the time. As a result, Afghanistan’s civil war problem has become even more intractable. The trauma has inadvertently helped normalize the use of violence as a means for goal achievement and problem resolution. It also makes the Afghan security forces less effective because they recruit from a population beset with mental illness. Finally, excessive exposure to torture, rape, and war motivates Afghans to continue rebelling because all of those trauma victims hold some individual or group responsible for their pain.

Why External Intervention Fails

Since initiating combat operations against al Qaeda and the Taliban in October 2001, America has deployed nearly three million military members and more than 2,000 Americans have lost their lives in Afghanistan at an estimated financial cost of $840 billion. Forty-one other countries have contributed to the Afghan war in varying degrees too.100

These gargantuan efforts have achieved very little. In 2001, just before the United States sent them fleeing, the Taliban controlled or contested 90 percent of the country with an estimated force of 35,000. Today, the Afghan government barely controls or influences half the country, despite having a security force 10 times larger than the Taliban’s, not to mention the benefit of 16 years of American combat power, expertise, and money.101 Nearly 17 years after the United States initiated Operation Enduring Freedom, Afghans are not even safe, much less free. Freedom House currently gives the country its lowest possible rating — “not free” — the same rating it gave Afghanistan in 2001.102 The assessment also remains abysmal for corruption, with Transparency International ranking Afghanistan below 96 percent of all other countries in the international system. More broadly, one of America’s main goals in invading Afghanistan — to destroy and defeat al Qaeda and other terror groups with global reach — appears further out of reach now than when the war on terror began. Back then, the State Department’s list included only al Qaeda and 12 other similarly motivated groups, comprising an estimated 32,000 fighters. Now the number of groups has mushroomed to 44, and their adherents have swelled to an estimated 110,000.103

It is likely that the war continues because, despite the efforts of the United States and the international community, the drivers of endless war in Afghanistan have not been addressed. No doubt the U.S. surge in 2010 temporarily depleted the Taliban’s ranks, but when the time came for Afghan security forces to take responsibility for their nation’s security, they showed themselves incapable or unwilling. Regardless of the reasons, after 16 years of being trained and equipped by the world’s mightiest military, Afghan security forces — more than 350,000 strong — continue to cede ground to a much smaller, shoddily equipped insurgency. Although GDP per capita has increased, Afghans remain in the bottom 10 percent for the world, which keeps rebel recruitment costs low.104 And despite the rhetoric and assurances, insurgents still find refuge in Pakistan (as well as in Afghanistan’s vast mountain ranges).

The motivation for rebellion also remains high. Afghans have every right to be angry with their government. Outside observers rate Afghans as not free and the government at near rock bottom for corruption, and they judge that the government has failed to provide its citizens with security and basic goods or services. Ethnic fractionalization runs rampant, intensified by the ongoing trauma and erosion of trust that accompanies war. Hundreds of billions of dollars that poured in from America and the international community unwittingly incentivized corruption and drug smuggling within the government and insurgent groups, often blurring the lines between friend and foe. Moreover, the lucrative opium trade motivates insurgent groups to keep the war going so they can conduct their illicit activities with little government interference.

Finally, the decades of bone-jarring trauma — including that from the U.S. invasion and follow-on military operations — have fundamentally changed Afghans. Violence has become normalized. The threshold at which aggrieved citizens will use deadly force against members of their own government has been lowered, making continued war more likely. The mental health care needs of Afghans likely outstrip the capabilities of nongovernmental organizations and exceed the time commitments that any Western liberal democracy could reasonably make. Even if and when widespread trauma finally subsides to a comparatively normal level, Afghans will likely be unable to self-govern peaceably and stably until the negative effects dissipate over time.

Recommendations for U.S. Policymakers

Withdraw American military forces from Afghanistan. Little or no correlation appears to exist between American efforts in Afghanistan and the ability or willingness of Afghans to fundamentally change the situation on the ground. Each year U.S. leaders say that gains are being made and that next year will be different, yet it never is. American blood and treasure should not be spent on a mission that only makes sense if the years of evidence are ignored. Additionally, America’s reputation abroad will continue to suffer as long as the country supports an Afghan government that ranks at the bottom on freedom and at the top on corruption. Moreover, the use of military force in Afghanistan and other Muslim-majority states has hardened anti-American sentiments. Survey data indicate that more citizens in a number of Muslim-majority states agree than disagree with the statement, “The US presence in the region justifies attacks against the US everywhere.”105 Those countries include the likes of Jordan, Kuwait, and Iraq. And finally, the Taliban threat does not necessitate a continued American military presence in Afghanistan.

Since 2001, the United States has been conducting a social experiment in Afghanistan (and the broader Muslim world) with its employment of military force and simultaneous attempts to establish democratic governments. Early in the war on terror, President George W. Bush spoke of a “global democratic revolution” led by the United States, a revolution that has, to date, failed.106 America’s political leaders sought to address the underlying causes of terrorism and usher in a sustained period of peace. Quite the opposite has happened. A decade and a half later, Afghans remain “not free” and their government continues its horrible record on civil rights and political liberties.107 Elsewhere in the Islamic world, more civil wars now rage and terror activity has increased substantially. Instead, future U.S. military interventions should occur only when a vital national interest is at stake.

Incorporate Population’s Mental Health Status Into Military Planning And Intelligence Estimates. The U.S. military has adapted significantly during the war on terror. Intelligence estimates that once focused on the physical terrain and enemy capabilities now analyze the “human terrain” — the psychological, cultural, and behavioral attributes of the populations American forces seek to protect.108 Military members have learned the languages, customs, and histories of the countries in which they fight. However, when fighting insurgencies, more is needed.

Just as the Department of Defense now recognizes the significant effects that PTSD and other mental health problems can have on its own troops after the war, U.S. military planners and national security policymakers should account for a foreign nation’s mental health status before intervening in its civil war.

For instance, had planners and policymakers analyzed the Afghan population before embarking on a decade and a half of nation building, the analysis would have cast significant doubt on the prospects for peace and the ability of Afghans to implement a functioning democracy — likely the most challenging form of government. Similarly, before getting further involved in any number of ongoing conflicts, such as those in Yemen, Syria, and Somalia, planners and policymakers would be well served by estimating how much trauma the populations have already endured, what that trauma has done to their mental health, and the extent to which violence norms have changed and endless war has become the new normal.

If military planners and national security policymakers continue to ignore the impact of trauma and a population’s mental health status, then they will fail to account for important factors that affect the very war outcome they seek to control.

Incentivize a more effective, less corrupt Afghan government. Finally, if policymakers demand a continued American presence in Afghanistan, then the focus should switch from military force to economic and diplomatic power. To date, American dollars have unwittingly fueled corruption with perverse incentives for Afghan government officials. To keep the money flowing, most Afghan government officials likely believe they need U.S. troops to remain, and that requires continued conflict. However, America could turn its approach to financially supporting Afghanistan upside down. Future funding could be tied to improvements in Afghan governance (e.g., provision of goods and services to its citizens, a reduction in corruption, and more political freedoms). Conceivably, then, the amount of aid flowing in would increase as the situation improves, until leveling off and eventually declining as Afghan self-sufficiency is restored. American diplomatic efforts should shore up enduring agreements from the international community, preferably through the United Nations, to both decrease costs to the American taxpayer and bolster the perception that Afghanistan is an international (rather than U.S.) mission. Even this approach, though, is fraught with risk, as substantial scholarship has found little or no relationship between aid and economic growth or basic human development indicators.109

Conclusion

The United States invaded Afghanistan in 2001 to destroy al Qaeda, remove the Taliban from power, and ensure that the country would not become a sanctuary for transnational terrorists again. Sixteen years later, those objectives are largely unmet. Al Qaeda has not been defeated, and the number of other Islamist-inspired terrorist groups has proliferated. The Taliban no longer constitute the national government, but they do control, influence, or contest almost half of Afghan districts, while the nominally democratic government ranks at or near the bottom of all states in capacity, transparency, and freedom. Additionally, terror groups like ISIS appear to be increasingly active within the country. U.S. efforts have largely failed and will continue to fail because of the dysfunctional features of a society that only Afghans can fix.

Instead of focusing on changes around the margins, the United States should take a step back and ask why Afghanistan has been at war for 40 years and why no one has been able to end it. The opportunity for war continues to exist, grievances remain at elevated levels, and two generations have come of age within the Afghan trauma state. As a result, America should decrease its military footprint and focus on efforts to incentivize a more capable, less corrupt Afghan government.

Beyond Afghanistan, America should restrain its use of military force to those instances vital to U.S. interests, since sustained war in already traumatized states like Afghanistan increases psychological trauma and societal instability, making victory unlikely. Finally, in those rare instances when the United States finds it necessary to apply military force in other countries’ civil wars, the population’s mental health status should be included in military planning and intelligence estimates because it will certainly affect the conduct of the war.

Appendix

The Trauma Index

To create the composite trauma index, it is first necessary to ensure all components of the index are comparable, that is, measured on the same scale. Measures for torture, war, rape, and other trauma are standardized using one of two methods — min-max or z-score. Each score is then converted to a scale of zero to 100, in which zero represents the least trauma and 100 represents the most trauma for each index.

For example, the trauma measure includes two variables: the CIRI Human Rights Data Project (torture) and the Political Terror Scale. The range of possible scores is 0–2 and 1–5, respectively. To combine these two variables into the single trauma index, each variable is converted to the same scale of zero to 100. First, since a CIRI score of zero represents the most amount of torture, the index is flipped such that a score of 2 now indicates the highest degree of torture and zero the lowest. Next, the score is converted to a 0-to-100 scale by multiplying the score by 50, in which a score of 2 on the CIRI index becomes 100, 1 becomes 50, and so on. Finally, the Political Terror Scale is mapped from the 1-to-5 scale by multiplying by 20, in which a score of 1 becomes 20, 4 becomes 75, and so on. Now that the two indexes lie on the same 0-to-100 scale, the composite trauma index is created by taking the simple average of the two scores by adding each score and dividing by two (i.e., the number of variables). (The complete codebook is available upon request.)

To estimate the prevalence of rape, I developed a measure based on Dara Kay Cohen and Ragnhild Nordås’s previous work on rape and sexual violence during military conflicts.110 I compiled a dataset using annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices produced by the U.S. Department of State (1990–2015). The methodology and scoring criteria followed Cohen and Nordås, who used an ordinal scale from zero to 3.111 Assessments of rape as “massive,” “systematic,” or a “tactic to [punish, terrorize, etc.]” are scored a 3. “Common,” “widespread,” and “serious problem” receive a 2. Characterizations of rape such as “some reports” or “a problem” were scored 1. Countries not meeting any of the above criteria received a zero. The qualitative assessments contained in the annual State Department reports were derived from a number of sources, including government data, assessments from nongovernmental organizations, and news accounts. The min-max method was used to normalize the data.

The term “rape” occurs more frequently over time in the State Department reports. Reviewing the reports in reverse chronological order, it appeared that the frequency of “rape” began to decrease substantially from 1998 to 1997. I then conducted a statistical analysis to investigate whether a significant change in frequency occurred over time. The chi-square results indicated a significant and positive relationship between year and use of “rape”: a more recent year corresponded with an increase in use of the term. As a result, I added three more possible scores for all years before 1997. If the report indicated that sexual violence was “widespread” or a “serious problem,” I recorded a 0.75. If the report characterized sexual violence as “a problem,” then the country received a score of 0.5. Finally, if the report did not include any of the above conditions but did describe domestic violence as “widespread” or a “serious problem,” the country would be scored 0.25 because domestic violence, sexual violence, and rape share a strong association.112

The actual number of reported rapes, when available, was not considered for several reasons. First, a sample of countries that included both quantitative and qualitative measures of rape was analyzed and the results indicated no statistically significant relationship, at p-value < 0.10, between the characterization of rape and the number of reported rapes in a country. Second, rape is considered an underreported crime but different country reports provide substantially different estimates regarding the degree of underreporting, and some country reports make no mention of underreporting at all. Third, analyzing reported numbers would bias the scoring against those countries that have police forces that citizens trust to report crime to, as well as those states with government bureaucracies that maintain and publicize crime statistics.

For the war variable measuring area magnitude, the data come from the Political Instability Task Force State Failure Problem Set. Scores range from zero (lowest area magnitude score for a country at war) to 4 (greatest area magnitude). A score of zero indicates that “less than one-tenth of the country and no significant cities” are affected, and a 4 means the war affects “more than one-half of the country.” I normalized scores such that a 4 corresponds to 100 points, a 3 to 80 points, and so on, with zero corresponding to 20 points. In cases where no war occurred (and the task force, therefore, provided no score), I assigned the respective country-year zero points.113

Notes

The author thanks Nikolaus Pittore for his valuable research.

1. Meredith Reid Sarkees and Frank Wayman, Resort to War: 1816–2007 (Washington: CQ Press, 2010).

2. Noor Ahmad Khalidi, “Afghanistan: Demographic Consequences of War, 1978–1987,” Central Asian Survey 10, no. 3 (1991): 101, 106, 108.

3. Larry Goodson, Afghanistan’s Endless War: State Failure, Regional Politics, and the Rise of the Taliban (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), p. 5.

4. Bill Roggio and Alexandra Gutowski, “LWJ Map Assessment: Taliban Controls or Contests 45% of Afghan Districts,” FDD’s Long War Journal, September 26, 2017, www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2017/09/lwj-map-assessment-taliban-controls-or-contests-45-of-afghan-districts.php.

5. iCasualties.org, “U.S. Fatalities in and around Afghanistan,” Operation Enduring Freedom, http://icasualties.org/oef/; Jeanne Sahadi, “The Financial Cost of 16 Years in Afghanistan,” CNN Money, August 22, 2017, http://money.cnn.com/2017/08/21/news/economy/war-costs-afghanistan/index.html; ISAF Troop Contributing Nations,” October 1, 2009, www.nato.int/ISAF/structure/nations/index.html;Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress,” July 30, 2014, p. 5, www.sigar.mil/pdf/quarterlyreports/2014-07-30qr.pdf">pdf/quarterlyreports/2014-07-30qr.pdf; and Watson Institute, “US Veterans and Families,” Costs of War website, http://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/veterans. Other cost estimates are even higher. See, for example, Neta Crawford, “US Budgetary Costs of Wars through 2016: $4.79 Trillion and Counting; Summary of Costs of the US Wars in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan and Pakistan and Homeland Security,” Watson Institute, September 2016, http://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2016/Costs%20of%20War%20through%202016%20FINAL%20final%20v2.pdf; and Linda Bilmes, “The Financial Legacy of Iraq and Afghanistan: How Wartime Spending Decisions Will Constrain Future National Security Budgets,” Faculty Research Working Paper no. RWP13-006, Harvard Kennedy School, March 2013, https://research.hks.harvard.edu/publications/workingpapers/citation.aspx?PubId=8956.

6. All names of Afghans and Afghan locations have been changed.

7. The civil war literature refers to the desire for financial profit as the “greed” or “rebellion-as-business” approach to civil war.

8. Transparency International, Corruption Perception Index 2016, www.transparency.org/news/feature/ corruption_perceptions_index_2016.

9. Martin Ewans, Afghanistan: A Short History of Its People and Politics (New York: Harper Perennial, 2002), pp. 122, 136, 153, 158–59.

10. Sarkees and Wayman, Resort to War.

11. Amin Saikal, A. G. Ravan Farhadi, and Kirill Nourzhanov, Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival (London: I. B. Tauris, 2012), p. 193; and Angelo Rasanayagam, Afghanistan: A Modern History; Monarchy, Despotism or Democracy? The Problems of Governance in the Muslim Tradition (London: I. B. Tauris, 2005), p. 114.

12. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, “Quarterly Report,” pp. 88, 101, 104.

13. Averages derived from data provided in Ibrahim Elbadawi and Nicholas Sambanis, “How Much War Will We See? Explaining the Prevalence of Civil War,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 46, no. 3 (2002): 307–34.

14. World Bank, “GDP per Capita (Current US$),” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=AF.

15. Megan McCloskey et al., “Behold: How the US Blew $17 Billion in Afghanistan,” ProPublica, December 18, 2015, www.pri.org/stories/2015-12-18/behold-american-taxpayer-what-happened-nearly-half-billion-your-dollars; and Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparison: GDP per Capita (PPP),” The World Factbook, www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2004rank.html.