Executive Summary

The United States has long been the world’s leading arms exporter. In 2018 the Trump administration notified Congress of $78 billion in major conventional weapons sales, giving the United States 31 percent of the global arms market. Between 2002 and 2018 Congress was notified of more than $560 billion in sales of major conventional weapons to 167 different nations.1

Although arms sales can play an important role in American foreign policy, the risks involved with sending billions of dollars of deadly weapons to all sorts of places are significant. The Arms Export Control Act of 1976 requires the executive branch to produce a risk assessment to ensure that the risks do not outweigh the potential benefits of selling major conventional weapons. Unfortunately, however, recent history strongly suggests that the risk-assessment process is broken.

Over the past decade American weapons have wound up in the hands of the Islamic State and other terrorist groups, sold on the black market in Yemen and elsewhere, have been used by oppressive governments to kill their own people, and have enabled nations to engage in bloody military conflicts. More broadly American arm sales have helped prop up authoritarian regimes, encouraged military adventurism, spurred arms races, and amplified existing conflicts. The reality is that the United States will sell weapons to almost any nation seeking them regardless of the potential risks involved.

Concerns about these negative consequences have risen of late. In April 2019, the Senate joined the House in passing a war-powers resolution requiring the United States to stop supporting Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen. Although the United States has no troops in Yemen, it has enabled and fueled the war through billions of dollars in arms sales to the Saudis over decades. In the wake of Trump’s predictable veto of that resolution, a bipartisan group of senators introduced the Enhancing Human Rights in Arms Sales Act, designed to ensure that “U.S. manufactured weapons are not used in the commission of heinous war crimes, the repression of human rights, or by terrorists who seek to do harm to Americans and innocent civilians abroad.”2

To help improve decisionmaking about arms sales we have created the Arms Transfer Risk Index. By identifying the factors linked to negative outcomes, such as dispersion, diversion, and the misuse of weapons by recipients, the index provides a way to measure the risk involved with arms sales to every nation. Although it is by no means an exact science, the index can help policy makers incorporate the potential risks of arms sales and make better decisions about which nations should receive American weapons.

We invite scholars and policy makers to read the report below, and download the data for further analysis.

Data

Arms Sales Risk Index Methodology

What are the risks of arms sales?

The potential negative side effects of arms sales take many forms. One extreme example is blowback — when American weapons end up being used against American interests. After the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the revolutionary government took possession of billions of dollars’ worth of American fighter jets and other weapons, an arsenal that Iran uses to this day. A more common example is when American troops end up fighting other forces armed with American-made weapons that the United States had willingly provided, as happened in Somalia in 1991 with weapons that were provided to that country during the Cold War.

Arms sales can also harm the regions into which weapons flow.One such example is dispersion — when weapons sold to a foreign government end up in the hands of criminal groups or adversaries. This risk is highest with sales to fragile states that are unprepared, unwilling, or too corrupt to protect their stockpiles adequately. For instance, despite America’s efforts to train and equip the Iraqi army, in 2014 ISIL fighters captured three Iraqi army divisions’ worth of American equipment, including tanks, armored vehicles, and infantry weapons.

American arms sales can also prolong and intensify interstate conflicts. Although the goal might be to alter the military balance of a conflict to facilitate a speedy end, sending weapons can also encourage the recipients to continue fighting even with no chance of success, leading to more casualties.

Finally, U.S. weapons sold to battle terrorism and insurgency undermine U.S. national security, especially when the purchaser is a corrupt regime or a nation with a history of human-rights violations. American firepower can enhance regime security and enable oppressive governments to mistreat minority groups and engage in inhumane acts against insurgents or terrorist groups. Currently, Saudi Arabia is waging war in Yemen, primarily using American weapons that the United States has continued to provide even though the Saudis have been cited repeatedly for human-rights violations and for targeting civilian populations.

In countries where serious corruption is endemic, American weapons can be diverted from their intended recipients and wind up in the wrong hands. For example, as a result of military and police corruption, the small arms and light weapons that the United States sends to Mexico and to several other Latin American countries to support the war on drugs often facilitate the very crimes they were meant to stop.

Unfortunately, no historical data exists that would allow analysts to measure how often these various outcomes occur or under what circumstances they are more or less likely. Such data should be collected. For the present, however, we must assess risk by relying on historical and analytical work on arms sales and their impacts to identify factors that are likely to increase the probability of negative consequences.

Given the limits of our current knowledge, we take what we believe to be a conservative approach based on straight-forward assumptions about the correlations between risk factors and negative outcomes on data that are available. We do not claim to make precise predictions about the probability of specific outcomes based on the Arms Sales Risk Index. The index’s immediate usefulness lies in helping policymakers incorporate the consideration of risks in decisions about selling American weapons abroad. In the long run the index is an important step in developing a more empirically-grounded assessment of the consequences – both positive and negative – of arms sales.

Constructing the Index

The Arms Sales Risk Index contains four risk vectors. Each vector, in essence, represents a causal mechanism or an explanation of how arms sales can lead to negative consequences. We measure the strength of each of these vectors by assessing six components. The risk vectors include a state’s level of corruption; its stability; its treatment of its own people; and the level of conflict, both internal and external, in which it is engaged.

To be included in the Arms Sales Risk Index a risk factor had to meet the following criteria:

- It had to be mentioned in the literature or logic had to strongly suggest its inclusion;

- It had to be something people can measure in a reliable fashion;

- The data source had to be one that is regularly updated;

- The data source had to be a credible one that used a transparent methodology;

- The component had to complement and not overlap too much with other components already in the index.

The first risk vector we consider is the corruption of the recipient nation’s regime. We assume that states that prevent its citizens from earning income, have fraudulent elections, or engage in questionable business practices pose a greater risk of misusing weapons, being involved with weapon dispersion, and having human-rights abuses. To assess this factor, we rely on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, which ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of corruption. It includes 16 different surveys from a dozen different institutions to create a composite “corruption perception score.”

The second risk vector we consider is the stability of the recipient nation. We assume that fragile states with tenuous legitimacy, that lack ability to deliver services and cannot manage conflict within their borders, to pose a greater risk for weapon dispersion and misuse of weapons. The Fragile States Index produced by the Fund for Peace examines international conditions that lead to state fragility. It works by examining when these pressures outweigh a state’s capability to maintain stability. It uses 12 indicators (security apparatus, factionalized elites, group grievance, economic decline and poverty, uneven development, human flight, state legitimacy, public services, human rights, demographic pressures, refugees, and external intervention) to create a composite score for “state fragility.”

The third risk vector we examine is a state’s behavior toward its citizens. States that have a poor record of human rights and/or regularly use violence against its citizens pose a greater risk of misusing weapons. We rely on two indices to measure these factors: the Freedom House’s Freedom in the World index and the U.S. Department of State’s Political Terror Scale.

The Freedom House’s index includes measurements for electoral process, political pluralism and participation, functioning of government, freedom of expression, associational rights, rule of law, and personal autonomy.

The State Department’s scale is an annual report measuring physical integrity and rights violations worldwide. It looks at political violence and terror that a country experiences in a particular year based on a five-level terror scale.

Finally, we consider conflict as a critical vector for negative consequences. States currently engaged in conflict are inherently riskier when it comes to factors such as weapon dispersion, blowback, entanglement, and human-rights abuses. To assess these risks, we rely on two sources. The Global Terrorism Index is published annually by the Institute for Economics and Peace. It provides a comprehensive summary of global trends and patterns in terrorism since 2000. For any given year, it looks at the total number of terrorist incidents, the total number of fatalities caused by terrorism, the total number of injuries caused by terrorism, and the approximate level of total property damage caused by terrorism. It combines these factors to create a composite score that ranks the amount of terrorism facing 163 countries. The second source is the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP)at the department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, and the Centre for the Study of Civil War at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). The UCDP/PRIO “Armed Conflict Dataset” is used to track the severity of armed conflict. It uses three measures (high-level, low-level, and no conflict) to assess the strength of a conflict in a given location. Larger conflicts are inherently riskier because of their longer duration and greater damage.

One methodological consideration worth noting is that there is certainly some overlap across indices. For example, the Fragile State Index includes variables that measure the presence of conflict, as do the Global Terrorism Index and the UDCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset. But, as the correlation matrix below indicates, even though all the variables are positively correlated, each appears to bring something different to the index.

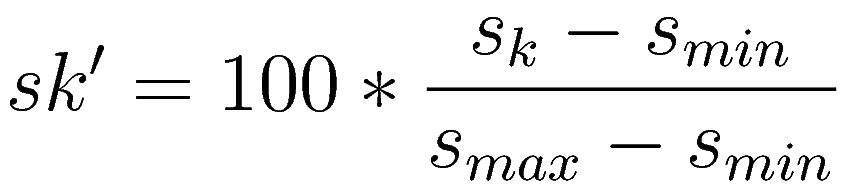

In order to combine each of the risk factors, which are constructed using a variety of different scales, we began by normalizing the scores for each risk factor. We normalized the variables using min-max methods. Unless otherwise noted, normalization follows the following formula:

where sk′represents the normalized score of the measurement variable s for observation k.

After normalization, every country has a scorebetween 1 (the lowest risk) to 100 (the highest risk) for each measure. We then weighted each of the six components equally,averaging them to find the composite risk score for each country. We choose to weigh the six components equally rather than the four vectors because we do not yet have any empirical reason to consider different weighting systems and because, although they are similar, the pairs of factors that measure state behavior and conflicts measure very different types of specific data. It is worth noting thattwo countries may have the same overall score, but they may be risky for different reasons. Thus, it is important to pay attention to the individual components as well as their risk index score.

The result of this process is a common-sense index that provides a starting point for policymakers to rethink the risk-assessment process, although it unavoidably sacrifices the nuance of the individual components. But because our approach measures only significant differences in state freedom, stability, and so forth, rather than attempting to claim undue precision, there is good reason to believe that nations scoring higher on this index are indeed riskier customers even though we cannot be certain about the precise weighting of different components (an area for future research).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.