Is public schooling a public good, a merit good, or a demerit good? Public schooling fails both conditions specified in the standard economic definition of a public good. In order to place public schooling into one of the remaining two categories, I first assess all of the theoretical positive and negative externalities resulting from public schooling as opposed to publicly financed universal school vouchers. Then, in an original contribution to the literature, I quantify the magnitude and sign of the net externality of government schooling in the United States using the preponderance of the most rigorous scientific evidence.

While the counts of theoretical positive and negative externalities are about equal, the empirical evidence leads me to estimate that public schooling in the United States has a net negative externality of at least $1.3 trillion—over the lifetime of the current cohort of children in government schools—relative to publicly funded universal school vouchers. I conclude with three policy recommendations: (1) the U.S. government should not operate schools at the local, state, or federal level on the basis of schooling’s being a public good; (2) U.S. citizens should not fund government schooling indirectly through the tax system on the basis of schooling being a merit good; and (3) the United States should instead fund education directly—rather than schooling—through a universal Education Savings Account (ESA) program.

Introduction

“No schooling was allowed to interfere with my education.”

— Grant Allen, Rosalba: The Story of Her Development, p. 101

Horace Mann, often called the father of American public schooling, and others argued that government-run common schools were necessary to bring together children from diverse backgrounds and to inculcate a uniform set of American values that would contribute to a stable and cohesive democratic society.1 In common schools, children from all backgrounds could learn how to interact with one another and become proper citizens.2 Mann traveled to Prussia to examine its system of common schools in 1843.3 He helped pass the first modern compulsory schooling attendance law in the United States in his home state of Massachusetts in 1852.4 Within seven decades, every state had followed suit; Mississippi was the last state to pass a compulsory schooling attendance law in 1918.5

Taxpayer-funded and government-run schools exist in all 50 states. This likely is attributable to many people with good intentions, like Mann, thinking that common schools could improve society overall.6 In general, a better-educated populace should result in positive social effects, all else being equal.

However, there are opportunity costs to maximizing education. For example, someone who pursues 10 college degrees may achieve a well-rounded and advanced education without contributing much to other individuals in society.7 And, of course, schooling and education are not one and the same. The formal definition of “education” is “the act or process of imparting or acquiring general knowledge, developing the powers of reasoning and judgment, and generally of preparing oneself or others intellectually for mature life.”8 Since schooling is but one channel available for an individual to acquire an education, it is important for the current study to examine the externalities of the actual policy in place in the United States — traditional public schooling — rather than some ideal policy that could hypothetically increase education for all children.

Schooling as a Public Good

The economic argument for government using coercion to fund — and even operate — a specific good or service is strongest for a good or service deemed to be a “public good.” The formal definition of a public good is attributed to Nobel laureate economist Paul Samuelson. In a classic 1954 article he explained that such a good satisfies two necessary conditions: (1) it is nonexcludable, and (2) it is nonrivalrous in consumption.9

The nonexcludability provision means that the producer cannot prevent nonpayers from using the good without bearing costs that exceed the benefit of payment. This provision is important because nonexcludability leads to a potential free-rider problem: individual consumers can enjoy the benefits of a product without directly paying for it. Consequently, the market may underprovide the good in question, or even fail to provide it at all. A feasible policy solution is to provide and produce the good publicly. In other words, the free-rider problem could be eliminated if all members of society were forced to pay for the service indirectly through taxes.

The nonrivalry provision simply means that one individual’s consumption of the good does not diminish the abilities of others to consume it. A radio station can be thought of as a true public good. Because it would be extremely difficult to prevent anyone with a radio from listening, the good is considered nonexcludable. And because one person’s consumption of the service does not affect whether the rest of society can listen, the radio is considered nonrivalrous. One policy implication could be to have taxes fund local radio stations. However, the market avoids the potential free-rider problem with radio stations by using advertisements as a funding source.

If schooling were indeed a public good, there would perhaps be a stronger economic argument for government funding and operation of schools. However, schooling easily fails both parts of the economic definition. If one student occupies a seat in a classroom, another child is prevented from sitting in the same seat. In addition, if students are added to a given classroom, the teacher is less able to tailor the educational approach to each child, which could reduce the average amount of personalized education received by each student. Because of this, schooling fails the nonrivalrous part of the definition. Second and perhaps most important, because it is not difficult to exclude a person from a school — or any other type of institution with walls — schooling fails the nonexcludability condition. If someone does not pay me to educate the student, I can simply deny the student services. Fortunately, schools will never suffer from a true free-rider problem because they are not true public goods. That is precisely why private schools and tutoring services operate effectively today without government operating or funding them.

Schooling as a Merit Good

When people, including prominent education scholars, say that schooling is a public good, I believe they mean that schooling is “good for the public.”10 Or, as an economist would say, schooling is a “merit good” because it has net positive externalities.11 An economic externality occurs whenever a voluntary transaction between two parties affects an involuntary third party in a positive or negative way. The original argument regarding economic externalities has to do with pollution — a negative externality.12 When I buy a car from a factory, the car manufacturer benefits from the transaction because it gets my money, and I benefit from the transaction because I get a car. Because the transaction is voluntary (and not coerced), it would only occur if both parties perceived that expected benefits would exceed expected costs.13 However, the rest of society could be involuntarily harmed by the transaction because they must breathe air that is less clean. Consequently, the market may produce a number of automobiles that is higher than the socially optimal level, where total social costs exceed total social benefits. As Arthur Pigou pointed out, one way to internalize the negative externality of pollution is to reduce consumption of automobiles toward the socially optimal level by taxing each unit of production — what is now called a Pigouvian tax.14

In the case of education, the externality is expected to be positive, which would make education a merit good. If I purchase an education through a school or otherwise, I benefit from the transaction because I will be able to command a higher salary in the future, and I will feel good about being an educated citizen. The education provider benefits from the transaction financially. And the rest of society is better off because of the benefits I provide to society as a result of my education, but for which I don’t earn a market income. For instance, the educational blogs, lectures, and journal articles I post for free on the internet help society (I hope). Also, as an educated citizen, I am less likely to break the law and more likely to cast an informed vote on Election Day.15 According to economists, leaving education to purely private transactions would result in education falling below the socially optimal level.16 A feasible policy solution to move education levels up is a negative Pigouvian tax, also known as a Pigouvian subsidy. As Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman concluded, government may have a role in funding schooling because of the theoretical positive externalities — or “neighborhood effects” — of education in general.17

While education itself seems to have net positive externalities, the case is less clear for the system of traditional public schooling we have in the United States today. After all, if the traditional public schooling system is reducing overall levels of education, or producing education very inefficiently, it would be considered a demerit good — a good that has net negative externalities. In this analysis, I examine all the theoretical externalities around the traditional public schooling system in the United States today.

In addition, I make the first attempt to calculate the net externality of traditional public schools relative to a realistic counterfactual: a private school of choice that could accept the public school’s per pupil funding amount as full payment for tuition and fees. Of course, the comparisons made here are not between traditional public schools and no schooling at all. If families were not forced to allocate 100 percent of their publicly raised educational resources to their assigned public schools, they could take those same funds to schools of their choosing. The three externalities that I examine are (1) an educated populace, (2) taxpayer costs, and (3) social cohesion.

Existing Literature

The most rigorous and relevant literature that we have comparing traditional public schools to private alternatives are analyses of private school choice programs. The best-known type of private school choice program, championed by Milton Friedman, uses vouchers that allow families to take their publicly raised education funds to the school of their choice.18 When parental demand for educational vouchers exceeds the supply of voucher funding, random lotteries are typically used to determine which families are able to exercise private school choice. The lottery setting allows social scientists to experimentally evaluate the effects of access to private school choice programs — and the effects of private schooling in general — on students. Since random chance determines who gets access to the program, the only difference between treatment and control groups is that one group received access to a private school choice program. Because several experimental evaluations exist on the effects of private school choice programs on student achievement, I exclude less rigorous studies that are not able to establish causal relationships from this review. For example, the empirical methodologies used in the 2013 book by Lubienski and Lubienski did not allow the authors to make causal claims because they simply examined the association between school type and math test scores after controlling for some observable characteristics such as race and gender.19

Educated Populace

Society benefits from a better-educated populace because individuals are more likely to interact with people who could teach them something new. In addition, better-educated citizens may produce high-quality goods and services that benefit the rest of society. For example, when a hard-working individual completes medical school, he or she benefits the rest of society by providing valuable services. The relevant positive externality can be thought of as the extent to which productive abilities are increased by the policy alternative (i.e., private school choice vs. residentially assigned public schooling).

A meta-analytic and systematic review of 19 experimental voucher studies around the world finds that, on average, private schools increase math scores by 15 percent of a standard deviation and reading scores by 27 percent of a standard deviation.20 Out of the 17 voucher experiments in the United States, 11 find statistically significant positive test-score effects for some or all students, four find no statistically significant effects, while two find negative effects.21 The meta-analysis from 16 of the U.S. experimental studies finds that, on average, private schooling does not have a statistically significant effect on reading scores, but it increases math scores by around 7 percent of a standard deviation.22

The scientific evidence on longer-term educational outcomes such as high school graduation rates is less abundant. Foreman’s summary of three rigorous studies linking private school choice programs to high school graduation finds positive effects.23 The only U.S. experiment on the subject finds that attending a private school through the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program increased the likelihood of high school graduation by 21 percentage points.24 The one quasi-experimental study on the subject finds that attending a private school using the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program increases the likelihood of high school graduation by 3 percentage points.25 The final study included in the review finds that Milwaukee private schools graduate voucher students at a rate 12 percentage points higher than Milwaukee public schools; however, this study is merely observational.26

Taxpayer Costs

In theory, all taxed funds are a negative externality if taxed individuals do not consent to the transaction. If citizens refuse to pay taxes, they must gain citizenship elsewhere or go to jail, both of which come with extraordinarily high transaction costs. Nonetheless, this analysis takes a conservative approach by comparing the taxpayer costs associated with traditional public schools to the policy-relevant counterfactual: the taxpayer costs incurred from a private school choice program.

We can examine the taxpayer effects of private school choice programs by looking at how current school choice laws affect statewide educational funding formulas. As shown in Forster’s review of the evidence, 25 out of 28 studies find that private school choice programs save taxpayer money, while 3 studies find no statistically significant fiscal effects.27 Spalding finds that 10 voucher programs in the United States generated a cumulative savings of at least $1.7 billion between 1990 and 2011.28 Since the 2016 Forster review, all other fiscal impact studies of private school choice programs that I know of have found taxpayer savings.29

This savings happens for two main reasons: (1) school voucher laws usually mandate that the voucher amount must be a fraction of the total per pupil expenditure in traditional public schools; and (2) private school tuition fees are often below the state-mandated maximum voucher funding amount.

As shown by EdChoice, the average state-funding amount allocated toward voucher students is around 59 percent of the per pupil funding in traditional public schools.30

Social Cohesion

A given educational setting can result in positive externalities if it results in a more cohesive society. An improved education could strengthen the character skills necessary to follow the law and tolerate the views of others. Furthermore, an educational setting can improve social cohesion through increasing racial diversity and integration. If someone is less likely to break the law because of character education, that person will be less likely to steal from others in society, and if someone is more tolerant of others, that person will be more likely to interact with society peacefully. Finally, if children grow up around diverse populations of students, they may be more likely to get along with people from different backgrounds as adults.

As shown in a review of 11 experimental and quasi-experimental studies, DeAngelis finds that private school choice programs in the United States increase these types of civic outcomes.31 None of the studies reviewed find negative effects. The only study linking private school choice to adult criminal behavior finds that the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program leads to a 7 percentage point reduction in felonies and a 6 to 9 percentage point reduction in misdemeanors for male students.32

DeAngelis also finds that effects of private school choice are null to positive for tolerance of others, positive on charitable giving, positive on volunteering, and null to positive on political participation.33 Wolf’s review of 21 quantitative studies similarly finds that private school choice increases civic outcomes overall.34 Forster’s review of the empirical evidence also finds that private school choice in the United States has null to positive effects on civic values and practices.35 Nine out of the 10 quantitative studies linking private school choice to racial integration find statistically significant positive effects, while one study finds no effects.36 Notably, Egalite, Mills, and Wolf find that, by using the Louisiana Scholarship Program, 82 percent of student transfers increased racial integration for their former public schools and 45 percent of student transfers improved racial integration in their new private school.37

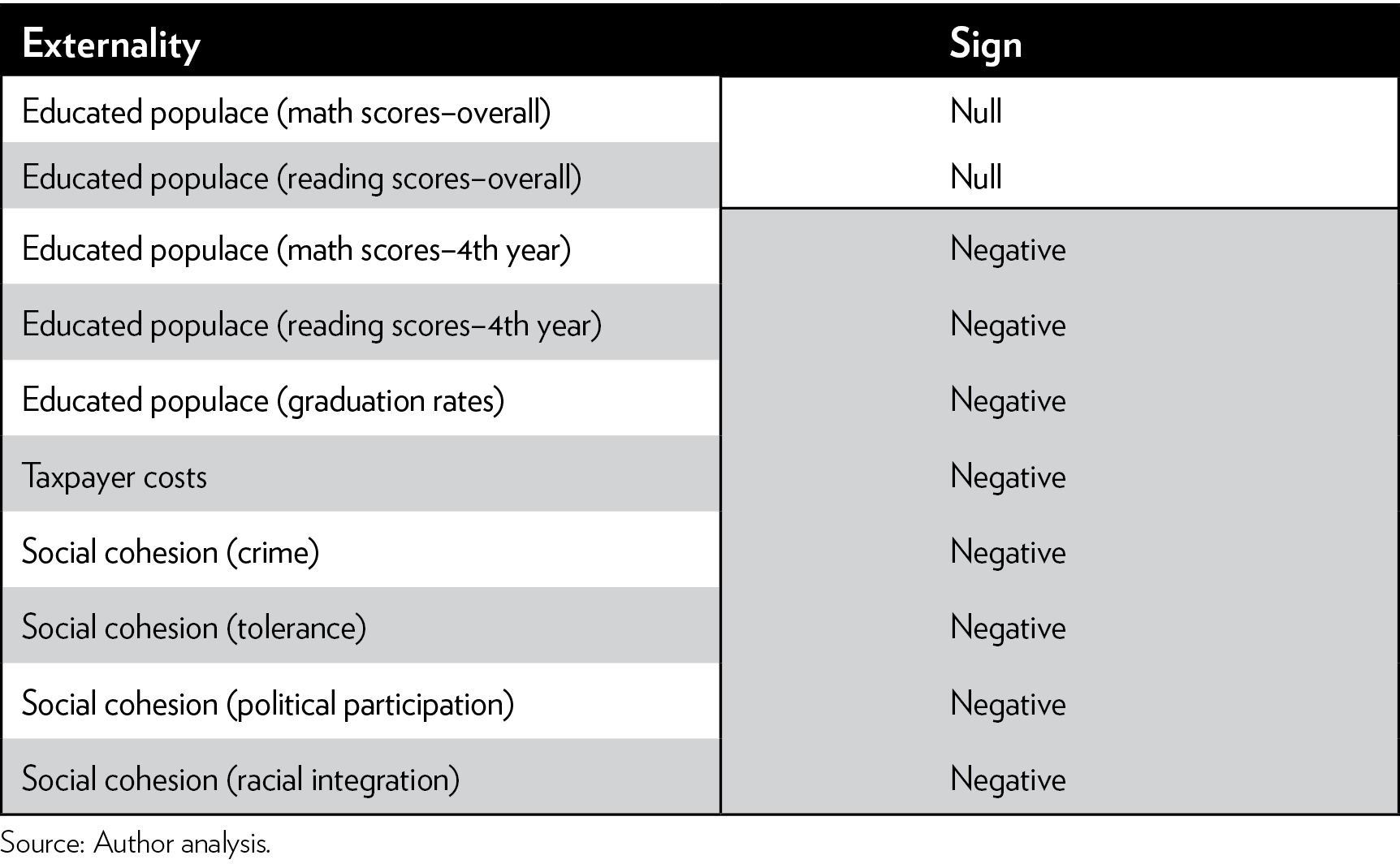

According to the existing evidence, government schooling appears to have negative effects on society through a less-educated populace, higher taxpayer burden, less tolerance, more crime, and racial segregation. A vote count of the evidence can be found in Table 1 below:

Table 1: Government-schooling externalities and their signs

Note: “Null” indicates that the preponderance of the evidence suggests that government schools do not have statistically different effects on society than private schools of choice. “Negative” indicates that the preponderance of the scientific evidence suggests that government schools produce socially less-desirable outcomes than do private schools of choice.

Data and Analysis

Using data from the Digest of Educational Statistics, I can quantify public schooling externalities associated with a less-educated populace, a larger taxpayer burden, and less social cohesion relative to publicly financed universal school vouchers. Specifically, the data allow me to quantify the externalities associated with changes in test scores, high school graduation rates, taxpayer funding, and criminal activity.

Some 50.477 million children are expected to be enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools in the United States in the 2017–2018 school year.38 This population is relevant for my calculation of nationwide externalities of public schooling.

Educated Populace

For the societal effects of government schooling’s ability to educate the populace, I examine two outcomes: test scores and high school graduation. Overall, Shakeel, Anderson, and Wolf find that private school choice programs increase reading scores by 4 percent of a standard deviation and math scores by 7 percent of a standard deviation.39 Consequently, I estimate one model based on reading scores and the other based on math scores. However, the effect on reading scores is not statistically significant, so the externality associated with an educated populace is zero in the first model.

For math scores, I follow previous research linking standardized effect sizes with estimates found by Eric Hanushek.40 Hanushek estimates that a one-standard-deviation increase in student cognitive ability leads to a 13 percent increase in lifetime earnings. Additionally, only 70 percent of learning gains are retained from year to year.41 By multiplying those two estimates together, I can find the learning gains relative to the average U.S. worker.42 I use Bureau of Labor Statistics data to find average earnings for U.S. employees ($49,630) and assume that current students will work between the ages of 25 and 70, or 46 years.43 When I calculate the net present value of lifetime earnings, I assume a 1 percent yearly growth in average salaries and a 3 percent annual discount rate. Based on these assumptions, the net present value of lifetime earnings for the average U.S. worker coming from the public school system is $1,234,957. Using Hanushek’s estimates, the average lifetime earnings for U.S. students with access to 13 years of private school choice is $1,341,225.

Thus, the reduction in lifetime earnings for each student experiencing 13 years

of government schooling is $106,268 ($1,341,225 – $1,234,957). Multiplying this result by the number of students in government schools reveals an overall negative effect on lifetime earnings of $5.364 trillion ($106,268 × 50.477 million). Of course, one can argue that the lower amount of earnings is accrued to the individual rather than the rest of society. However, the decrease in earnings reflects a $5.364 trillion (in 2017 dollars) reduction in production within society overall. Since the lower level of production results from a less-educated populace and harms the rest of society as a whole, it is a negative externality of government schooling.

Alternatively, I can calculate this particular externality through the effects of private school choice programs on graduation rates. While the experimental study in Washington, D.C., finds that private schooling increases the likelihood of graduation by 21 percentage points, I use the much less substantial 3 percentage point increase in graduation rates found in the Milwaukee voucher analysis in order to provide a conservative estimate.44 I also use evidence from Levin, finding that each high school graduate produces around $277,000 (in 2017 dollars) in social benefits derived from additional tax revenues and reductions in health, crime, and welfare costs.45 Combining findings from Cowen (et al.) and Levin, I find that government schooling results in about 1,514,310 fewer high school graduates (50.477 million U.S. students multiplied by a 3 percentage point reduction in likelihood of graduation). This reduction leads to negative social effects of around $419.464 billion (1,514,310 fewer graduates multiplied by $277,000 in social costs each).46

Taxpayer Costs

There are two ways to calculate the effects on taxpayers of government schooling relative to private schools of choice. First, I use data from EdChoice showing that the average state-funding amount allocated to voucher students is around 59 percent of the per pupil funding in traditional public schools.47 According to the National Center for Education Statistics for 2013–2014, public education spending was around $625.016 billion in 2014 dollars. That is equivalent to around $656.019 billion in 2017 dollars. Multiplying this amount by the 59 percent found by EdChoice suggests that these students would cost $387.051 billion to educate, or around $268.968 billion less than in public schools. In other words, over the course of 13 years of k-12 schooling, the 50.477 million children in U.S. public schools would cost taxpayers an additional $3.497 trillion.

Second, I could compare the average tuition and fees charged in all private schools to the average per pupil expenditure in all public schools. According to the Digest of Education Statistics Table 205.50, average private school tuition was around $10,740 per student in 2011–2012, or around $11,633 in 2017 dollars. According to the Digest of Education Statistics Table 236.60, average public school per pupil expenditure was $11,991 in 2011–2012, or around $12,988 in 2017 dollars. In other words, it costs around $1,355 more ($12,988 – $11,633) to educate a child in a government school each year, on average. Over 13 years, this costs society an additional $17,615 per child. This costs taxpayers an additional $889.152 billion for 50.477 million children. This estimate is only about one-fourth the size of the taxpayer cost estimate in the previous paragraph because this estimate uses the average tuition level of all private schools rather than the tuition level of current private schools of choice in the United States.

Social Cohesion

This section is limited to the effects of government schooling on the future criminal activity of students because it is infeasible to quantify the effects of tolerance, political participation, and racial segregation on society overall. The only quasi-experimental study linking private school choice to crime finds that private schools reduce the likelihood that male students will commit felonies by 4 percentage points in Milwaukee.48 Assuming these benefits only accrue to about half of the 50.477 million U.S. students (the males), we should expect around 1.01 million fewer felons. McCollister, French, and Fang find that the social cost of a felony is around $23,242 in 2017 dollars.49 Thus, a 1.01 million increase in the number of felons, produced by government schools, leads to around a $23.474 billion increase in social costs. In order to provide conservative estimates, this analysis ignores the positive effects of the Milwaukee voucher program on reducing misdemeanors.

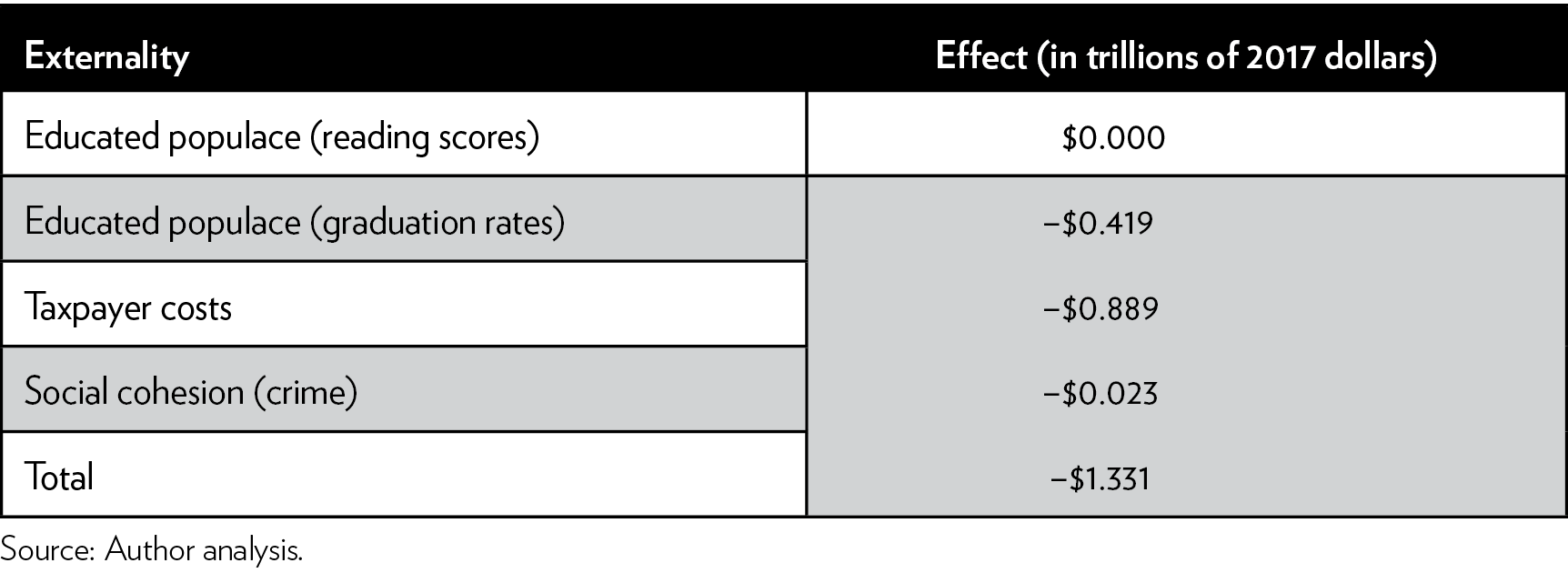

Table 2 : Conservative estimates of government-schooling externalities

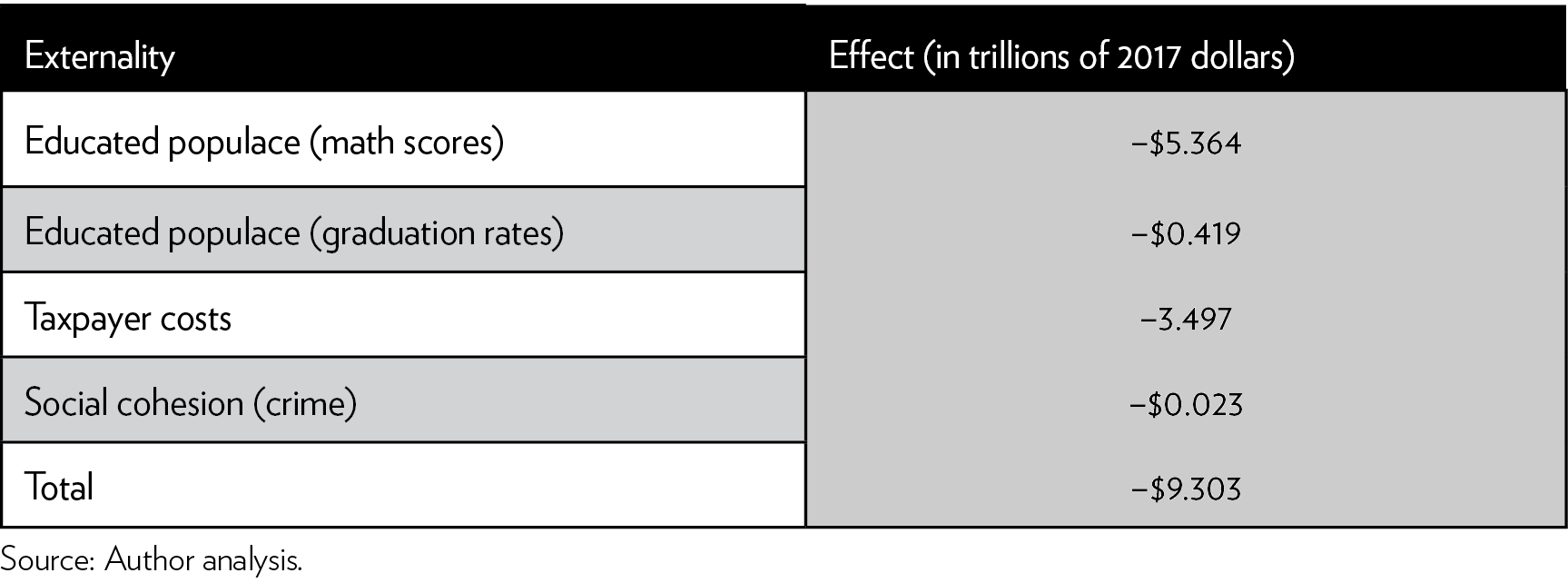

Table 3 : Alternative estimates of government-schooling externalities

Overall Results

The most conservative estimates of the externalities of government schooling in the United States can be found in Table 2, while alternative estimates can be found in Table 3 below. The results in Table 2 are more conservative because (1) they assume zero benefits accrue from the positive effects found for math achievement; and (2) they assume that the per pupil funding amount would be equal to the average private school tuition level rather than the average amount currently spent on a private school of choice. As shown in Table 2, this study reveals a net negative externality of government schooling of at least $1.331 trillion. This is a significant effect, as it is over 7 percent of the nation’s entire gross domestic product (GDP) recorded in 2016.50 Notably, this likely is a lower bound of the actual effect, as I have no monetized values for the social harms from less tolerance, political participation, and racial integration.

Table 3 indicates a net negative externality of around $9.303 trillion. By comparison, this would be equivalent to about half of the U.S. GDP in 2016. However, these estimates should be treated with caution because they combine the calculations of externalities from two academic outcomes, test scores and graduation rates. Nonetheless, even if the effect derived from changes in graduation rates is excluded from this model, the overall negative externality is $8.884 trillion, still about half of the 2016 U.S. GDP.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

Since schooling fails both the nonrivalry and nonexcludability conditions, there is no strong argument for government operation of schooling on the basis of the service being a public good.51 While public schooling is certainly not a public good, it may be “good for the public” if it increases overall education levels without any unintended consequences. Even Milton Friedman claims that, because schooling may be an economic merit good, a valid argument may be made for government funding of schools.52

However, because public schooling may not maximize one’s education, it may have significant negative externalities relative to a universal voucher program for schools of choice. Indeed, the results of this study suggest that publicly funded government-run schools, relative to private schools of choice, have substantial negative effects on U.S. society overall associated with a less-educated populace, less social cohesion, and increased taxpayer burdens. In 2017, the most conservative model finds a net negative externality of government schooling of around $1.331 trillion, over 7 percent of the U.S. GDP recorded in 2016, while the alternative specification finds that public schooling results in a net negative externality of about half of U.S. GDP in 2016. Note that these are lifetime estimates of the effects of government schools on 50.477 million children relative to whether they would have attended private schools of choice for 13 years in the United States.

Since government schooling in the United States results in a net negative externality relative to private schools of choice, we should not subsidize government schooling based on the economic argument that it is a merit good. According to the evidence, we should eliminate the negative externalities of government schooling by allowing families to reallocate their educational resources to the private schools that best serve their children. Specifically, states should pass legislation to enact universally accessible Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) to allow families to customize their children’s educational experiences. An ESA would allow society to educate children — rather than simply school them — by allowing parents to allocate education dollars toward various educational services such as schooling, tutoring, online instruction, textbooks, and even college costs. In addition, a universal program may provide the demand necessary for market entry. Market entry and competitive pressures could improve the diversity and quality of educational options available to children while reducing average educational costs.

Of course, not all school choice programs are created equal. Recent studies find that highly regulated private school choice programs can reduce school quality.53 In addition, regulation of private school choice programs could result in more negative externalities by incentivizing existing private schools to operate like current government schools.54 In order to reduce the externalities associated with government schooling, we should allow private schools to continue their specialized approaches by reducing the quantity and intensity of regulations linked to private school choice program funding.

Notes

- Horace Mann, Lectures on Education (Boston: L.N Ide, 1855); Benjamin Rush, “Thoughts upon the Mode of Education Proper in a Republic,” in Essays on Education in the Early Republic, ed. Frederick Rudolph (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965); and John Dewey, Democracy and Education (New York: Macmillan Company, 1916).

- Mann, Lectures on Education.

- Karl E. Jeismann et al., German Influences on Education in the United States to 1917 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 21–41.

- Forest C. Ensign, Compulsory School Attendance and Child Labor: A Study of the Historical Development of Regulations Compelling Attendance and Limiting the Labor of Children in a Selected Group of States (Iowa City, IA: Athens Press, 1921); and Michael B. Katz, The Irony of Early School Reform: Educational Innovation in Mid-Nineteenth Century Massachusetts (New York: Teachers College Press, 1968).

- William M. Landes and Lewis C. Solmon, “Compulsory Schooling Legislation: An Economic Analysis of Law and Social Change in the Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Economic History 32, no. 1 (1972): 54–91.

- Amy Gutmann, Democratic Education (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999).

- Bryan Caplan, The Case against Education: Why the Education System Is a Waste of Time and Money (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018).

- Dictionary.com, “Education,” http://www.dictionary.com/browse/education.

- Paul A. Samuelson, “The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure,” Review of Economics and Statistics 36, no. 4 (1954): 387–89.

- Henry M. Levin, “Education as a Public and Private Good,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 6, no. 4 (1987): 628–41; and Chris Lubienski, “Whither the Common Good? A Critique of Home Schooling,” Peabody Journal of Education 75, no. 1–2 (2000): 207–32.

- Richard A. Musgrave, “A Multiple Theory of Budget Determination,” FranzArchiv/Public Finance Analysis (1956/1957): 333–43.

- R. H. Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost,” Journal of Law and Economics 56, no. 4 (2013): 837–77; and Arthur C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare (London: Macmillan and Company, 1920).

- Richard A. Epstein, Free Markets under Siege: Cartels, Politics, and Social Welfare (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution, 2008).

- Pigou, The Economics of Welfare.

- Lance Lochner and Enrico Moretti, “The Effect of Education on Crime: Evidence from Prison Inmates, Arrests, and Self-Reports,” American Economic Review 94, no. 1 (2004): 155–89; and Andre Blais et al., “Where Does Turnout Decline Come From?,” European Journal of Political Research 43, no. 2 (2004): 221–36.

- Musgrave, “A Multiple Theory of Budget Determination,” pp. 333–43.

- Milton Friedman, “The Role of Government in Education,” in Economics and the Public Interest, ed. Robert A. Solo (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1955), pp. 123–44.

- Friedman, “The Role of Government in Education,” pp. 123–44.

- Christopher Lubienski and Sarah Lubienski, The Public School Advantage: Why Public Schools Outperform Private Schools (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

- M. Danish Shakeel et al., “The Participant Effects of Private School Vouchers across the Globe: A Meta-Analytic and Systematic Review,” University of Arkansas Department of Education Reform Working Paper No. 2016-07, May 2016, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2777633.

- Kaitlin P. Anderson and Patrick J. Wolf, Evaluating School Vouchers: Evidence from a Within Study Comparison, University of Arkansas Department of Education Reform Working Paper No. 2017-10, April 2017; John Barnard et al., “Principal Stratification Approach to Broken Randomized Experiments: A Case Study of Vouchers in New York City,” Journal of American Statistical Association 98, no. 462 (2003): 299–323; Joshua M. Cowen, “School Choice as a Latent Variable: Estimating the ‘Complier Average Causal Effect’ of Vouchers in Charlotte,” Policy Studies Journal 36, no. 2 (2008): 301–15; Jay P. Greene, “Vouchers in Charlotte,” Education Next 1, no. 2 (2001); Jay P. Greene et al., “Effectiveness of School Choice: The Milwaukee Experiment,” Education and Urban Society 31, no. 2 (1999): 190–213; William G. Howell et al., “School Vouchers and Academic Performance: Results from Three Randomized Field Trials,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 21, no. 2 (2002): 191–217; Hui Jin et al., “A Modified General Location Model for Noncompliance with Missing Data: Revisiting the New York City School Choice Scholarship Program Using Principal Stratification,” Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 35, no. 2 (2010): 154–73; Cecilia E. Rouse, “Private School Vouchers and Student Achievement: An Evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 113, no. 2 (1998): 553–602.; Patrick J. Wolf et al., “School Vouchers and Student Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from Washington, DC,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 32, no. 2 (2013): 246–70; Eric Bettinger and Robert Slonim, “Using Experimental Economics to Measure the Effects of a Natural Educational Experiment on Altruism,” Journal of Public Economics 90, no. 8–9 (2006): 1625–48; Marianne P. Bitler et al., “Distributional Effects of a School Voucher Program: Evidence from New York City,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 19271, July 2013; Alan B. Krueger and Pei Zhu, “Another Look at the New York City School Voucher Experiment,” American Behavioral Scientist 47, no. 5 (2004): 658–98; Jonathan N. Mills and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on Student Achievement after Three Years,” Louisiana Scholarship Program Evaluation Report #7, June 2017; Atila Abdulkadiroglu et al., “Free to Choose: Can School Choice Reduce Student Achievement?,” American Economic Journal 10, no. 1 (2018): 175–206; and Mark Dynarski et al., “Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Impacts after One Year,” National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance report, June 2017.

- Shakeel et al., “The Participant Effects of Private School Vouchers across the Globe: A Meta-Analytic and Systematic Review.”

- Leesa M. Foreman, “Educational Attainment Effects of Public and Private School Choice,” Journal of School Choice 11, no. 4 (2017): 642–54.

- Wolf et al., “School Vouchers and Student Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from Washington, DC.”

- Joshua M. Cowen et al., “School Vouchers and Student Attainment: Evidence from a State-Mandated Study of Milwaukee’s Parental Choice Program,” Policy Studies Journal 41, no. 1 (2013): 147–68.

- John R. Warren, “Graduation Rates for Choice and Public School Students in Milwaukee, 2003–2009,” School Choice Wisconsin, January 2011.

- Greg Forster, “A Win-Win Solution: The Empirical Evidence on School Choice,” EdChoice report, 2016, https://www.edchoice.org/research/win-win-solution/.

- Jeff Spalding, “The School Voucher Audit: Do Publicly Funded Private School Choice Programs Save Money?,” EdChoice report, September 2014, https://www.edchoice.org/research/the-school-voucher-audit/.

- Martin F. Lueken, “The Tax-Credit Scholarship Audit: Do Publicly Funded Private School Choice Programs Save Money?,” EdChoice report, 2016, https://www.edchoice.org/research/tax-credit-scholarship-audit/; Corey A. DeAngelis and Julie R. Trivitt, “The Fiscal Effect of Eliminating the Louisiana Program on State Education Expenditures,” University of Arkansas Department of Education Reform Working Paper no. 2016-06, August 2016; Julie R. Trivitt and Corey A. DeAngelis, “State and District Fiscal Effects of a Universal Education Savings Account Program in Arkansas,” University of Arkansas Department of Education Reform Working Paper no. 2017-04, March 2017; and Julie R. Trivitt and Corey A. DeAngelis, “State Fiscal Impact of the Succeed Scholarship Program 2016–2017,” University of Arkansas Department of Education Reform Policy Brief, March 2017, http://www.uaedreform.org/state-fiscal-impact-of-the-succeed-scholarship-program-2016-2017/.

- “School Choice in America,” School Choice in America Dashboard, https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/school-choice-in-america/#.

- Corey A. DeAngelis, “Do Self-Interested Schooling Selections Improve Society? A Review of the Evidence,” Journal of School Choice 11, no. 4 (2017): 546–58.

- Corey A. DeAngelis and Patrick J. Wolf, “The School Choice Voucher: A ‘Get Out of Jail’ Card?,” University of Arkansas Department of Education Reform Working Paper no. 2016-03, March 2016, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2743541.

- DeAngelis, “Do Self-Interested Schooling Selections Improve Society? A Review of the Evidence.”

- Patrick J. Wolf, “Civics Exam,” Education Next 7, no. 3 (2007).

- Forster, “A Win-Win Solution: The Empirical Evidence on School Choice.”

- Forster, “A Win-Win Solution.”

- Anna J. Egalite et al., “The Impact of Targeted School Vouchers on Racial Stratification in Louisiana Schools,” Education and Urban Society 49, no. 3 (2016): 271–96.

- “Enrollment in Elementary, Secondary, and Degree-Granting Postsecondary Institutions, by Level and Control of Institution: Selected Years, 1869–70 through Fall 2025,” Digest of Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_105.30.asp?current=yes.

- Shakeel et al., “The Participant Effects of Private School Vouchers across the Globe: A Meta-Analytic and Systematic Review.”

- Patrick J. Wolf et al., “The Productivity of Public Charter Schools,” School Choice Demonstration Project, University of Arkansas, July 2014; Corey A. DeAngelis and Ben DeGrow, “Doing More with Less: The Charter School Advantage in Michigan,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy report, 2018, https://www.mackinac.org/s2018-01; Corey A. DeAngelis et al., “Bigger Bang, Fewer Bucks? The Productivity of Public Charter Schools in Eight US Cities,” University of Arkansas Department of Education Reform report, 2018, http://www.uaedreform.org/bigger-bang-fewer-bucks-the-productivity-of-public-charter-schools-in-eight-u-s-cities/; and Eric A. Hanushek, “The Economic Value of Higher Teacher Quality,” Economics of Education Review 30, no. 3 (2011): 466–79.

- Hanushek, “The Economic Value of Higher Teacher Quality.”

- Since over 90 percent of U.S. children attend public schools, the overall average income in the nation should largely reflect their average income levels.

- “Occupational Employment Statistics: May 2016 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm#00%E2%80%930000.

- Wolf et al., “The Productivity of Public Charter Schools”; and Cowen et al., “School Vouchers and Student Attainment,” pp. 147–68.

- Henry M. Levin, “The Economic Payoff to Investing in Educational Justice,” Educational Researcher 38 no. 1 (2009): 5–20.

- Cowen et al., “School Vouchers and Student Attainment,” pp. 147–68; and Levin, “The Economic Payoff to Investing in Educational Justice,” pp. 5–20.

- “School Choice in America,” School Choice in America Dashboard.

- DeAngelis and Wolf, “The School Choice Voucher: A ‘Get Out of Jail’ Card?”

- Kathryn E. McCollister et al., “The Cost of Crime to Society: New Crime-Specific Estimates for Policy and Program Evaluation,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 108, no. 1 (2010): 98–109. I exclude the two most costly types of crime — rape and murder — from this calculation in order to provide a more conservative estimate.

- “United States GDP 1960–2017,” Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/gdp.

- Samuelson, “The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure.”

- Friedman, “The Role of Government in Education,” pp. 123–44.

- Yujie Sude et al., “Supplying Choice: An Analysis of School Participation Decisions in Voucher Programs in DC, Indiana, and Louisiana,” Journal of School Choice 12, no. 1 (2018): 8–33.

- Corey A. DeAngelis and Lindsey Burke, “Does Regulation Induce Homogenization? An Analysis of Three Voucher Programs in the United States,” University of Arkansas Department of Education Reform (EDRE) Working Paper No. 2017-14, September 2017, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3038201.