Paid parental leave provides workers with financial compensation during temporary absences following the birth or adoption of a child. Private companies often provide paid leave and the federal government mandates 12 weeks of job-protected unpaid leave, but recently policymakers and advocates have become dissatisfied with the status quo.

Proponents of federal intervention argue that the private market does not or cannot provide sufficient paid leave. Moreover, proponents believe government supported leave would improve labor market outcomes and reduce gender and labor-market inequality.

This study provides evidence that suggests otherwise. First, ample data show that the private market provides paid leave at rates about 30 to 50 percentage points higher than proponents claim. Private paid leave provision has grown three- or fourfold over 50 years and continues to grow. This trend indicates industry is responsive to employee demands.

Second, workers may not be better off under federal paid leave and may be worse off. Government intervention provides new incentives, and individuals are likely to adapt accordingly. Evidence suggests government supported leave may result in wage or benefit reductions, female unemployment, or reduced professional opportunities for women.

Government intervention is also unlikely to correct gender or labor-market inequality in ways proponents desire. For example, families may respond to the policy by increasing women’s household work contributions relative to men’s. Redistributive effects of government intervention are likely to harm workers.

This study concludes that policymakers should not adopt paid parental leave policies. Instead, they should consider improving workers’ lives through reforms that increase economic efficiency, remove barriers to flexible work, and increase choice.

Introduction

Paid parental leave provides financial compensation when employees are temporarily away from work following the birth or adoption of a child. Companies can provide benefits voluntarily or government can mandate or subsidize leave.1 When government mandates or subsidizes parental leave it is considered government-supported leave.

In the United States, paid parental leave is provided voluntarily by many employers. In addition, most workers qualify for 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave through the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) of 1993. But there is no federal paid leave program or mandate.

Some policymakers believe the status quo is lacking and have pushed for further government action. Five states and the District of Columbia have established paid parental leave programs since 2002, and many states have studied or introduced legislation.2 In 2017, the Trump administration proposed providing paid parental leave through state unemployment insurance,3 and congressional Democrats proposed federal subsidized leave funded through taxes on businesses and workers.4

Proponents of these measures often argue the private market cannot sufficiently provide paid leave due to collective action problems. They claim that government-supported leave would markedly improve workers’ lives by improving labor-market outcomes and reducing gender inequality. In this paper, I provide economic research and federal data that suggest otherwise.

First, abundant data show that the private market provides paid leave at much higher rates than advocates have acknowledged. Over the past 50 years, the private sector has substantially increased paid leave offerings; this suggests the private market responds to employee demands. At the same time, mothers’ labor-force engagement increased without government intervention.

Second, workers may not be better off overall with government-supported leave, and many may be worse off. Most advocates assume a static economic model, where parental benefits are provided and nothing else changes. That is unlikely because individuals respond to incentives.

In the simplest case, employers may offset the cost of government-supported leave by reducing worker wages or employee benefits. If employers cannot fully offset costs through wage reductions, then side effects such as increased female unemployment or reduced female professional opportunities may occur, even when leave is available to both genders.

Workers may also adjust their behavior in ways that do not meet advocates’ goals. For example, government-supported leave may increase women’s household-work contributions relative to men’s. Because higher-income working women with children are most likely to use parental leave, government-supported leave is likely to redistribute to this group and away from other groups.

This study concludes that policymakers should eliminate government rules that reduce economic efficiency and interfere with worker’s choices, including relevant labor and childcare regulations. This would make integrating work and family life easier, while sidestepping perverse efficiency and redistributive effects associated with government-supported leave.

The Private Market Provides Paid Family Leave

Proponents of government-supported leave are skeptical about the private market’s ability to provide adequate paid leave and believe that employees and employers face a collective action problem in obtaining or providing paid leave. They claim that 15 percent of workers have access to paid leave, based on a Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) figure. But the BLS figure does not include all paid leave options and benefits.5

The functional consequence of firms’ policies is that workers can take time off for family matters. In that sense, other survey evidence is likely to be a better guide than measures of official maternity- or paternity-leave programs.

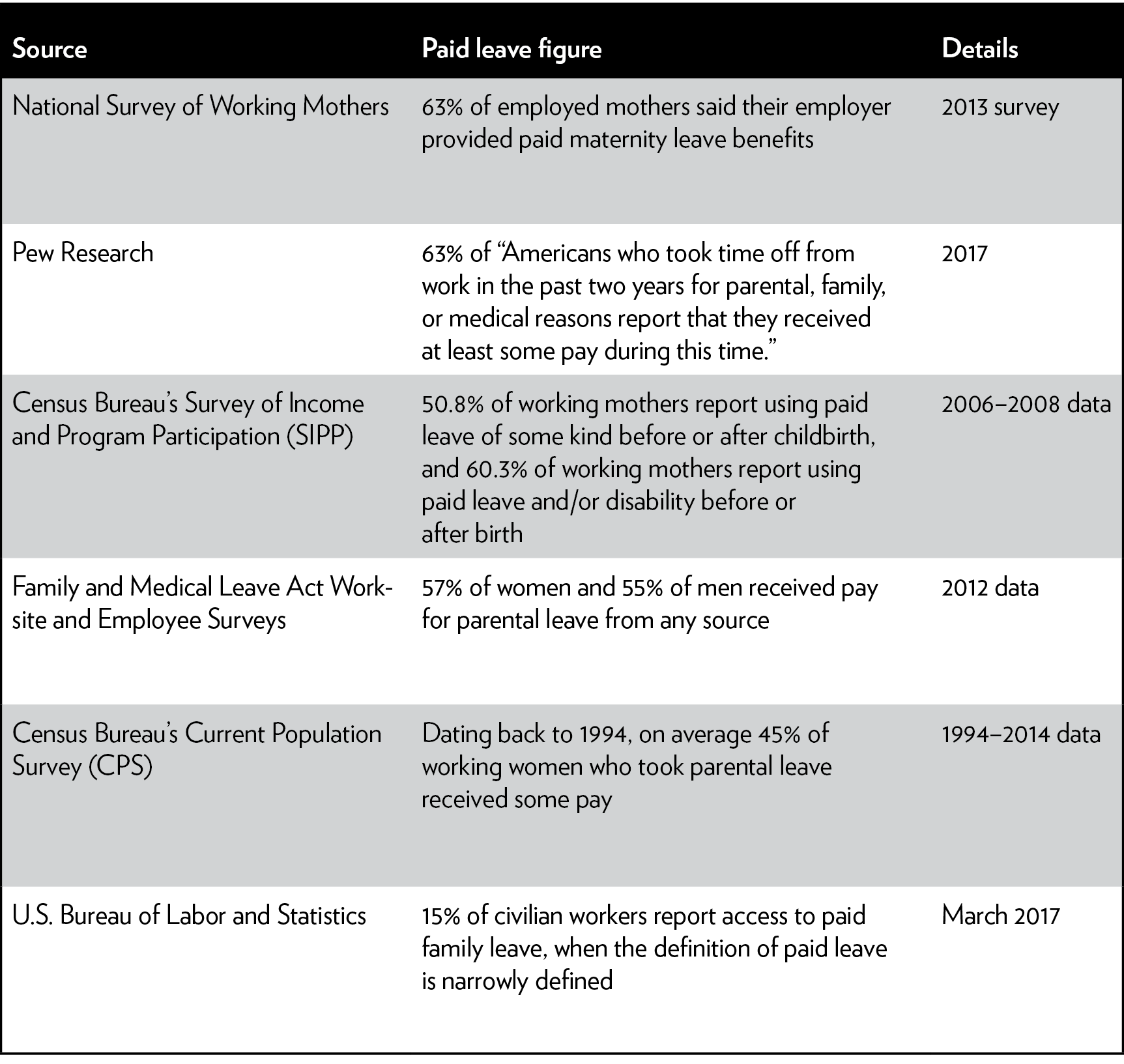

Using more comprehensive metrics, the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), Pew Research polling, and the National Survey of Working Mothers find that more than 60 percent of mothers or workers have access to paid leave (Table 1).6 Other government surveys estimate that the number is between 45 and 57 percent, substantially higher than the BLS figure.7

Table 1: Estimates of access to paid leave

Source: Barbara Gault et al., “Figure 1: Paid Parental/Family Leave Access and Usage Statistics from Five Federal Key Data Sources,” in “Paid Parental Leave in the United States: What the Data Tell Us about Access, Usage, and Economic and Health Benefits,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, U.S. Department of Labor, March 2014, https://www.dol.gov/wb/resources/paid_parental_leave_in_the_united_states.pdf; Eugene R. Declercq et al., “Listening to Mothers III: New Mothers Speak Out,” New York: Childbirth Connection, June 2013, http://Transform.childbirthconnection.org/reports/listeningtomothers/; Renee Stepler, “Key Takeaways on Americans’ Views of and Experiences with Family and Medical Leave,” Pew Research Center, March 23, 2017, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/03/23/key-takeaways-on-americans-views-of-and-experiences-with-family-and-medical-leave/; Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), “Employee Benefits Survey,” March 2017, https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2017/ownership/civilian/table32a.htm; and BLS, “National Compensation Survey: Glossary of Employee Benefit Terms,” April 11, 2017, https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/glossary20162017.htm.

Proponents of government-supported leave also worry that employers are not sufficiently responsive to employees’ paid-leave preferences. But access to paid leave has grown substantially over time and has accelerated as U.S. female labor force participation declined post-2000.

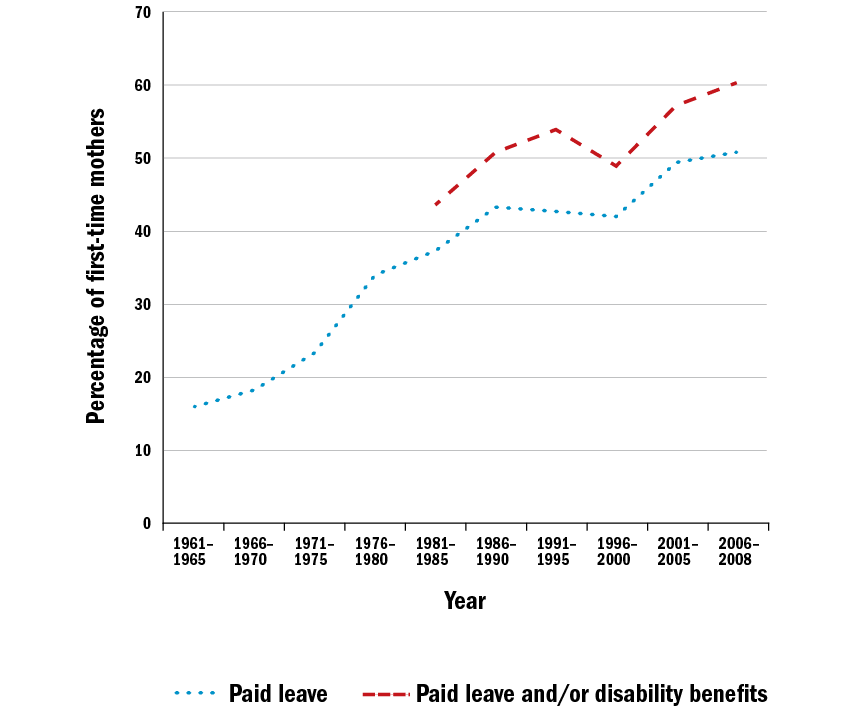

The share of first-time mothers who reported using paid leave and/or disability grew from 16 to 61 percent over 50 years (Figure 1).8 This represents a 280 percent increase and suggests the private market is responsive to employee demands.

Although the Census Bureau discontinued asking mothers about paid leave in 2014, there is reason to think paid leave provision continued to grow. Over 100 large name-brand companies have created or expanded paid family leave policies over the last three years,9 and a long list of major companies, including Walmart, Walgreens, Home Depot, Target, Starbucks, Amazon, FedEx, and McDonald’s, have created or expanded paid leave programs since late 2017 alone (Appendix A). The latter expansions apply to low-wage or hourly workers, not just high-wage or educated workers.

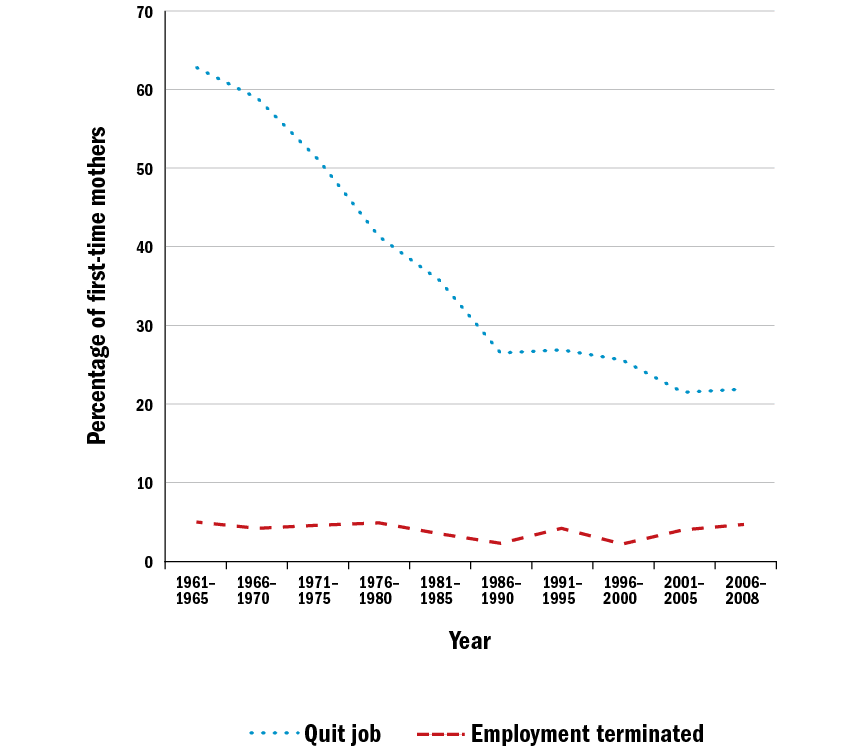

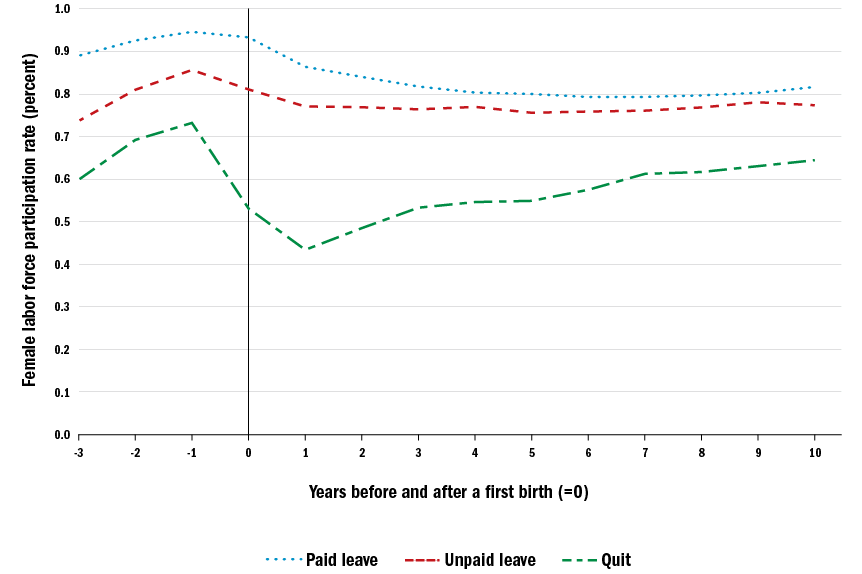

Working mothers’ labor-market engagement has also increased without government intervention. The share of first-time mothers who quit working declined significantly in past decades, from over 60 percent in 1961 to just over 20 percent in 2008 (Figure 2). This represents a 66 percent decline in first-time mothers who quit their jobs, in the absence of federal government-supported leave.

Figure 1 : First-time mothers’ leave use, 1961–2008

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, “Table 5: Selected Leave Arrangements Used by Women Who Worked during Pregnancy preceding First Birth: 1981–1985 to 2006–2008,” in “Maternity Leave and Employment Patterns of First-Time Mothers: 1961–2008,” U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, October 2011, https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p70-128.pdf; U.S. Census Bureau, “Table F: Leave Arrangements Used by Women Who Worked during Pregnancy: 1961–1965 to 1991–95,” in “Maternity Leave and Employment Patterns: 1961–1995,” U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, November 2001, https://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/p70-79.pdf.

Figure 2 : First-time mothers’ employment outcomes before and after birth

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, “Table 5: Selected Leave Arrangements Used by Women Who Worked during Pregnancy preceding First Birth: 1981–1985 to 2006–2008,” in “Maternity Leave and Employment Patterns of First-Time Mothers: 1961–2008,” U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, October 2011, https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p70-128.pdf; U.S. Census Bureau, “Table F: Leave Arrangements Used by Women Who Worked during Pregnancy: 1961–1965 to 1991–1995,” in “Maternity Leave and Employment Patterns: 1961–1995,” U.S. Census Bureau, November 2001, https://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/p70-79.pdf.

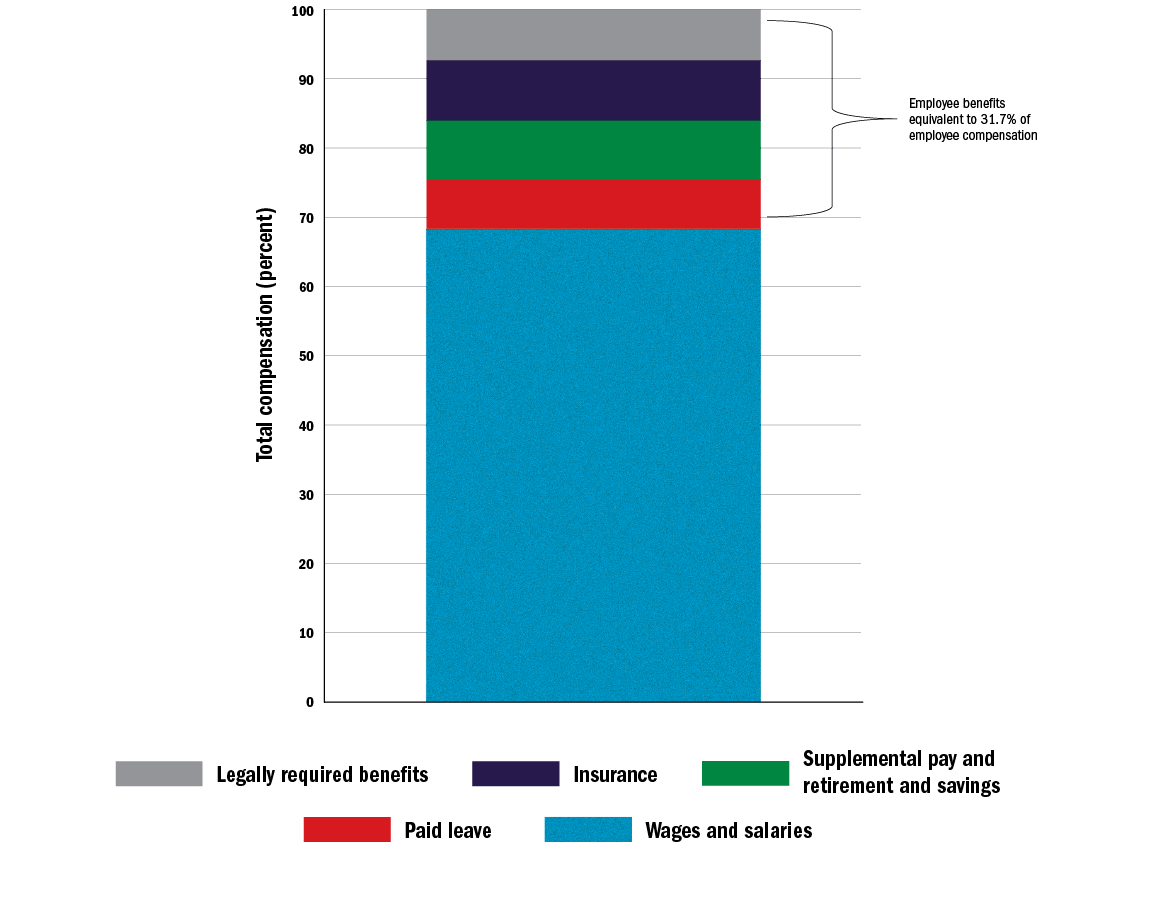

Between voluntary expansions in paid leave and more mothers in the workforce, U.S. companies are already spending sub-stantial resources on paid leave benefits. Thirty-two percent of an average U.S. worker’s total compensation is nonwage benefits (Figure 3), and more than 14 percent of workers’ compensation is paid leave and legally required social insurance programs.10 Employers spent an estimated $1.25 trillion on paid leave and other legally required benefits in 2016.11

Government Intervention May Have Minimal Effects

Advocates of government-supported leave seem to believe paid leave can be provided and nothing else in the economy will change. But whether the program takes the form of an employer mandate or is funded through a payroll tax, employers and employees will change their behavior in response to new incentives. In the simplest case, employers offset the cost of government-supported leave by reducing worker wages or employee benefits.

Imagine an employer that is currently paying an employee $10 per hour. The employer is indifferent toward providing compensation as wages or benefits but is interested in limiting business costs for a given productivity level. One way she can offset the effects of a mandate or new tax is by reducing wages but maintaining total compensation (see Figure 3).12 In this case, government-supported leave rearranges worker compensation, but the new benefit is not free to the worker.

Figure 3 : Breakdown of compensation for average U.S. worker in 2017

Source: U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employer Costs for Employee Compensation Archived News Releases,” BLS, Economic News Release, 2017, https://www.bls.gov/bls/news-release/ecec.htm#current.

Note: Includes private- and public-sector workers, except federal government employees and farm or private household workers.

Academic research supports this idea. Economist Lawrence Summers studied the effects of mandating government benefits and concluded that women’s wages would be reduced to reflect the cost. Summers states that “if wages could freely adjust, these differences in expected costs would be offset by differences in wages.” If not, “there will be efficiency consequences as employers seek to hire workers with lower benefit costs.”13

Summers’s predictions have been borne out in the real world. Economist Jonathan Gruber studied maternity-benefit mandates in Illinois, New York, and New Jersey, and his findings “consistently suggest” women’s wages were reduced to reflect the cost of benefits. The estimated reduction in wages was around 100 percent of the cost of benefits.14

Government-mandated leave has similar effects internationally. A study of 16 European countries over a period of around 20 years found that “parental leave is associated . . . with reductions in [women’s] relative wages at extended durations.”15 Other researchers have noted that “work-family policies . . . have also contributed to . . . lower wage-levels for women relative to men.”16

Mandated paid leave reduces employee wages indirectly, but subsidized paid leave programs reduce employee wages directly. Subsidized paid leave programs rely on payroll taxes borne by workers to fund paid leave benefits.

If government-supported leave reduces wages in favor of benefits, it may reduce worker’s economic utility.17 Cash benefits are flexible, and employee benefits are not. When employees prefer wages, government-supported leave makes them worse off.

Side Effects of Mandated or Subsidized Leave

Even if firms could fully offset costs by reducing wages there may be business-disruption costs associated with employees taking more leave.18 But firms may not be able to fully offset the cost of government-supported leave by reducing employee wages because of minimum wage laws, union contracts, or other reasons.

As a result, government-supported leave may produce side effects that reduce economic efficiency. These have a direct impact on women because women take the majority of parental leave, even when men are eligible. This gendered pattern exists even in egalitarian societies like the Nordic countries.19

Young women are more expensive than other workers under government-supported leave, so employers may be less likely to hire women or may limit training and leadership opportunities. In this case, government-supported leave increases gender-based discrimination in the labor market.

Husbands and wives may also change their behavior in ways that reduce efficiency. Some research suggests government-supported leave increases the amount of household work women do relative to men, even when government-supported leave is available to both sexes. (See the section “Household Labor.”)

Employment

Empirical research highlights employment effects. A study of California’s subsidized leave program found it increased unemployment and unemployment duration for childbearing age women by 5 to 22 percent and 4 to 9 percent, respectively.20 A recent review of the literature suggests “employers who find leave-taking costly may discriminate against female employees by being less likely to hire them.”21

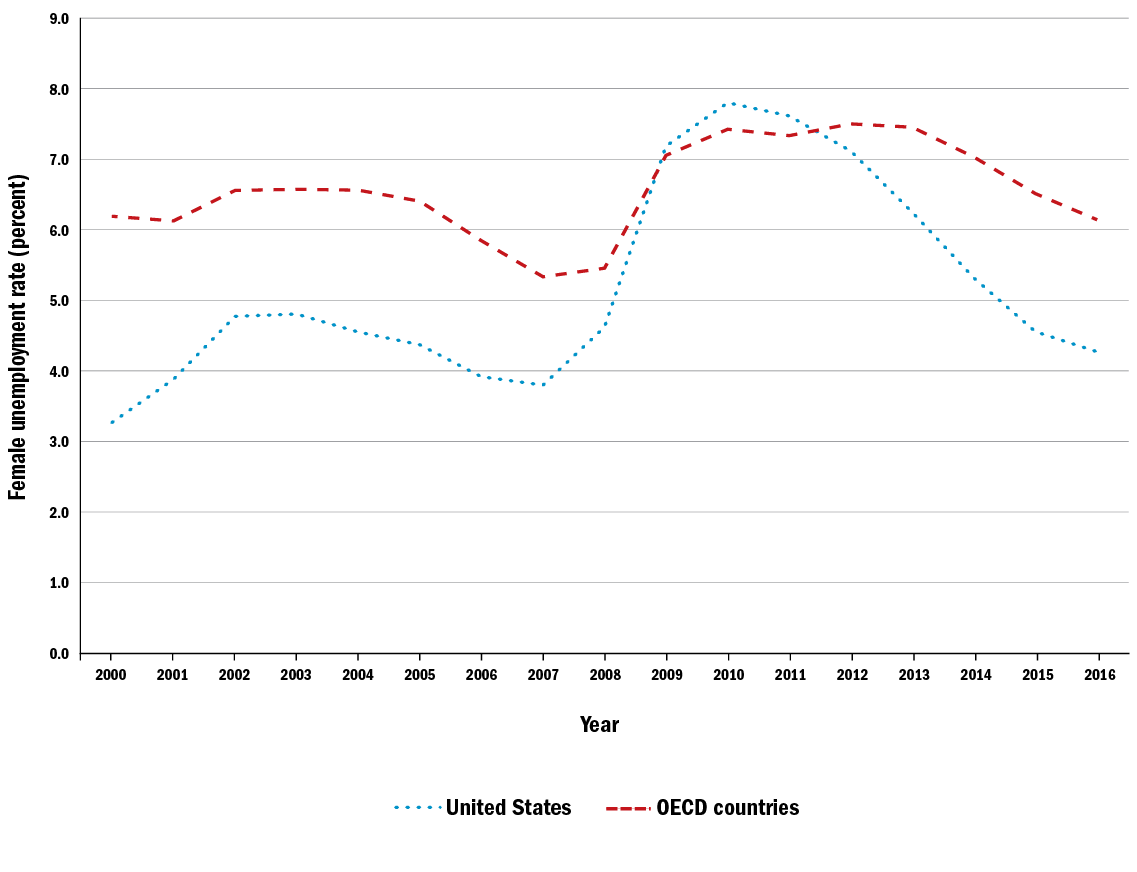

Although descriptive data do not constitute strong standalone evidence, female unemploy-ment is lower in the United States compared to non-U.S. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries with government-supported leave (Figure 4). Labor-force participation is higher for U.S. women than it is in the OECD overall. This pattern is consistent with the theory that government-supported leave increases discrimination against women in the labor market.

Government-supported leave may also change the type of employment women are engaged in. A study that compares the United States with other OECD countries finds that government-supported leave is associated with greater segregation in labor markets, with men and women more separated by industry. The authors find fewer female professionals and fewer women in leadership roles in countries with government-supported leave and other mothers’ work entitlements.22

Figure 4 : Postrecession, U.S. continues traditionally low female unemployment

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Labour Force Statistics by Sex and Age Indicators,” 2000–2016 data, https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54752.

Leadership

Research indicates government-supported leave affects female promotions and leadership. Economist Jenna Stearns studied two leave expansions in Britain and found that government-supported leave and job entitlements led to fewer women holding management positions and promotion-track jobs and “exacerbate[d] gender inequality among highly educated workers.”23 Stearns also found that mothers with low education were more than 10 percentage points less likely to be promoted within five years after the maternity-leave expansion.

Economists argue that so-called family-friendly policies may “have boomerang effects on women’s position in the labor market, especially for the more educated women,” and that women’s labor market position has deteriorated in the Nordic countries. The policies have inadvertently created a “system-based glass ceiling.”24

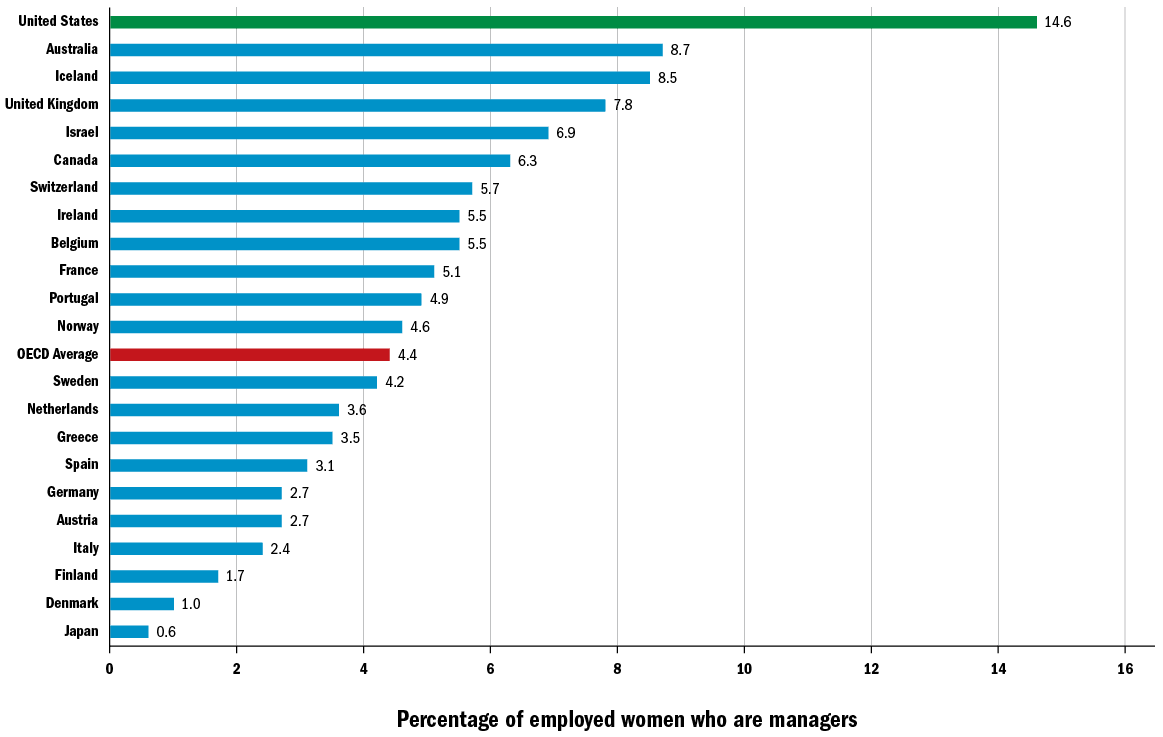

Figure 5: Higher share of women in the U.S. are employed as managers than in other OECD countries

One study suggests that the FMLA has had a similar impact in the United States: women hired after the policy went into effect were 8 percent less likely to be promoted than women hired before.25

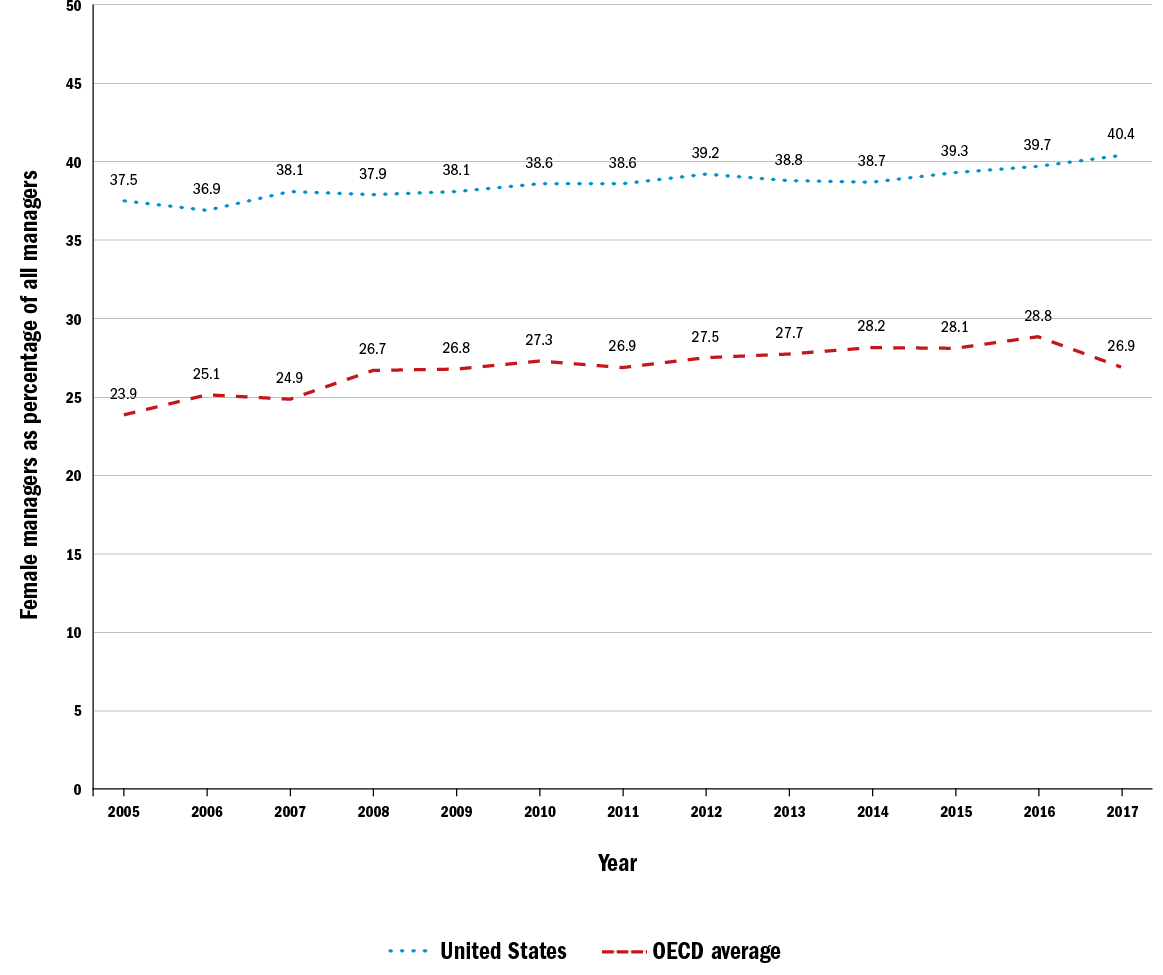

American women outperform internation-al counterparts along corporate leadership lines, although descriptive data alone do not provide robust independent evidence (Figures 5 and 6, Table 2). This is consistent with the theory that government-paid leave either increases gender-based discrimination in the labor market or reduces women’s quali-fying work experience, or both.

U.S. women are more likely to be employed as managers than women in any of 21 OECD countries with government-paid leave policies (Figure 5), and as a share of all managers, U.S. women have exceeded the OECD average for many years (Figure 6).26

According to OECD and World Bank data, the proportion of women employed as managers is three times higher in the United States than in Norway.27 Between 1980 and 2010, 4.5 million managers were added to the U.S. workforce, and women filled the majority (58 percent) of new positions.28

Figure 6: Higher share of managers in the U.S. are female compared to other OECD countries, 2005–2017

Source: International Labour Organization (ILO) Statistics: “Key Indicators of the Labour Market,” ILO, http://www.ilo.org/inform/online-information-resources/databases/stats/lang--en/index.htm.

Note: All OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries are included, but data for all countries are not available for all years. Data are specific to middle- and senior management positions. ILO estimates do not include hospitality, retail, and other service managers or general managers, which likely depresses the raw estimates somewhat.

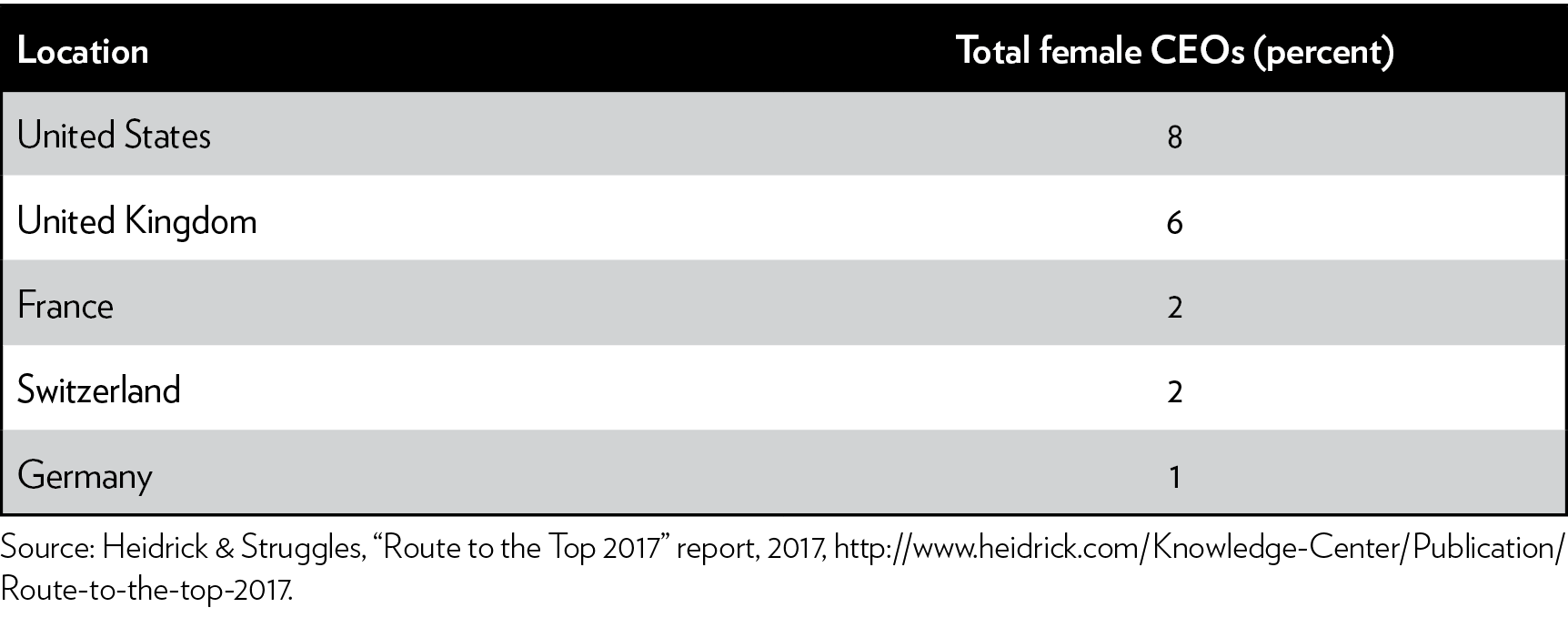

The United States also has a relatively high proportion of female CEOs. In the “Route to the Top” report, the United States has the highest proportion of female CEOs overall of any country measured (Table 2). The U.S. labor market seems to hold distinct leadership opportunities for women, in contrast to other labor markets worldwide.

Table 2: Female CEOs as a percentage of all CEOs

Household Labor

Proponents believe government-supported leave can help eliminate perceived household inequities. Husbands and wives may change their behavior in response to government-supported leave, but not in the way advocates expect. These changes may create inefficiencies.

Some research suggests long parental leaves create artificial incentives for women to increase time spent on cooking and housework compared with men. A study on parental time use in 19 countries over 40 years found “men do less and women do more time-inflexible housework in nations where . . . parental leave(s) are long.”29 According to the author, “parental leave makes women available for time-inflexible housework during a critical time of household negotiation, and it sends a clear message about who should provide family labor.”

As Kimberly Morgan and Kathrin Zippel argue, multiyear childcare leave policies common in Europe “are likely to reinforce the traditional division of care work in the home and temporary homemaking is . . . institutionalized as the norm for many women.”30 Likewise, Nima Sanandaji argues in “The Nordic Glass Ceiling” that government-supported leave and a variety of other social welfare policies have turned many Swedish women into part-time workers and part-time mothers.31

In line with this theory, government subsidized leave in California raised leave use by almost five weeks for the average covered mother and two to three days for the corresponding father,32 increasing mothers’ domestic contributions compared to those of fathers. According to one estimate, women with infant children increased the amount of time spent on childcare by 3.56 hours per day after the implementation of California paid leave.33

As male labor force participation has declined in the United States and women outpace men at school, reshuffling domestic and professional responsibilities may naturally occur in some partnerships.34 While supporters of traditional gender roles might find government-supported leave’s impact on household duties appealing, encouraging women to stay at home is not likely to be in the interests of all households.

Redistributive Effects of Mandated or Subsidized Leave

Government-supported leave is likely to redistribute from childless adults to those with children, from men to women, from male breadwinner households to other household types, and from low-income to middle- or high-income workers.35

First, government-supported leave requires childless adults to trade their own wages for parental leave other families will use.36 These costs may be felt more acutely by childless adults over time, since government-supported leave entitlements tend to grow. For example, Norway expanded leave from 18 to 35 weeks between 1987 and 1992, which nearly doubled the cost to taxpayers from $12,354 to $24,022 per eligible birth.37

Government-supported leave also redistributes from male to female workers. Men are more likely to be childless than women (25 percent compared to 15 percent at ages 40 to 44)38 and women take parental leave at significantly higher rates than men even when both sexes are eligible.39

Partly because men are less likely to take paid leave, government-supported leave would redistribute from male breadwinner households to dual-income and female breadwinner households. In the United States, male breadwinner households constitute 30 percent of families with children under 18.40

Government-supported leave is also likely to redistribute from one income class to another. In California, government-subsidized leave use is “concentrated among more highly paid workers,” and the median paid leave recipient earns $10,000 more than the median working woman.41

Figure 7 : Paid leave does not predict substantially higher U.S. female labor force participation 10 years after birth

Source: Claudia Goldin and Joshua Mitchell, “The New Lifecycle of Women’s Employment: Disappearing Humps, Sagging Middles, Expanding Tops,” NBER No. 22913, December 2016, http://www.nber.org/papers/w22913.

Likewise, expanding paid leave in Norway from 18 to 35 weeks regressively redistributed from low-income to middle- and upper-income mothers while raising taxes considerably. Mothers with higher incomes were more likely to meet eligibility standards for receiving the benefit, such as working 6 of the last 10 months. But even among eligible mothers, the parental leave benefit was regressively distributed.

In a study of this expansion, economists found that Norway’s leave “amount[s] to a pure leisure transfer to middle and upper income families at the expense of the least well off in society.” Expanding benefits had little impact on positive social outcomes, including labor force participation in the short or long run, fertility, marriage, or divorce, according to the study’s authors.42

Female Labor Market Outcomes and Government-Supported Leave

Economic efficiency and redistributive effects indicate women may not be better off overall under government-supported leave. However, proponents insist women’s lives could be improved because government-supported leave is linked to higher female labor force participation and smaller gender pay gaps.

Economics can’t tell us what the female labor force participation rate or unadjusted pay gap should be, but most economists would start from the premise that, with some exceptions, economic welfare is maximized when families make free choices.43 In a free market, individual outcomes, and by extension group outcomes, are not expected to be equal.

Moreover, there is reason to think metrics wouldn’t change in the direction proponents desire or would be perversely impacted by government-supported leave. A study of five expansions of maternity leave in Germany found that expansions “reduced mothers’ postbirth employment rates in the short run,” and long-run effects on labor market outcomes were small.44

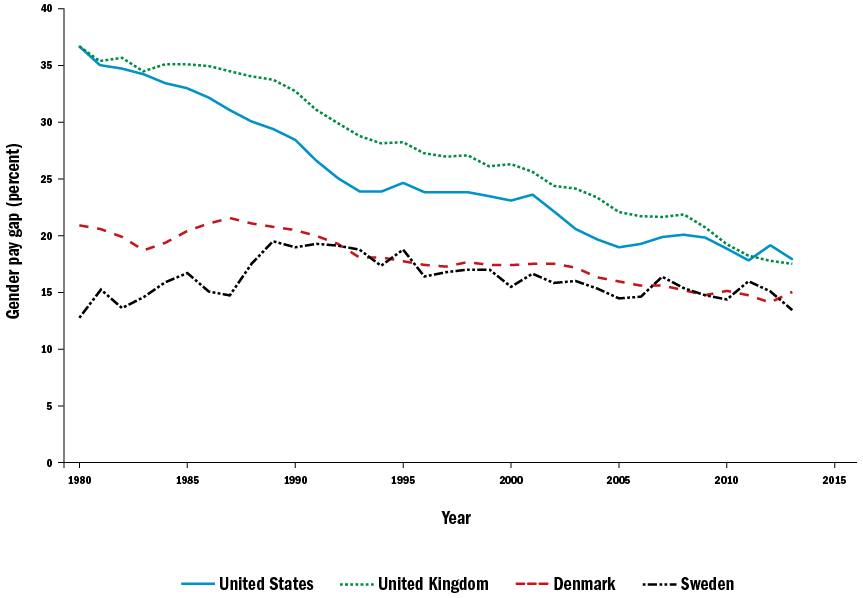

Figure 8 : The U.S. gender pay gap is converging with that of other countries

Source: Henrik Kleven, Camille Landais, and Jakob Egholt Sogaard, “Children and Gender Inequality: Evidence from Denmark,” NBER Working Paper no. 24219, January 2018, http://www.nber.org/papers/w24219.

U.S. research suggests paid leave does not predict substantially higher female labor force participation 10 years after birth (Figure 7). It’s likely that women offered paid leave by their employer have other characteristics that make them more likely to retain employment.

In countries where government-supported leave is linked to increased female labor force participation, it is a result of women doing more part-time work. Economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn find that women weakly attached to the labor force stay partly engaged as a result of government-supported leave.45

Women’s labor market outcomes also vary for other reasons. Economists argue the gender pay gap is converging across all countries, and “though [the United States and Sweden or Denmark] feature different public policies and labor markets, they are no longer very different in terms of overall gender inequality” (Figure 8).46

The size of the gender pay gap seems to have little to do with government-supported leave. According to one highly cited study, although gender pay gaps are “less pronounced in countries with developed family policies,” the lower gender pay gap “should be attributed to their more egalitarian wage structures” rather than paid leave entitlements.47

In other words, government-supported leave does not explain smaller gender pay gaps after considering public policies that reduce wage dispersion directly, including government rules that strengthen trade unions or limit minimum or maximum wages.

Policy Options

The private sector has grown its paid leave offerings in response to employee demands and continues to do so. Wage restructuring, efficiency, and redistributive effects may mean workers are no better off or are worse off overall with government-supported leave. Therefore, the federal government should not adopt a paid leave policy.

Instead, policymakers should think broadly about improving workers’ lives and focus on removing barriers to workers’ career choices and improving economic efficiency. Childcare regulations and existing labor laws impose some of the most significant barriers.

Childcare expenses are soaring in many states, and they are inflated by government policies that reduce the supply of care. Childcare expenses occur over many years and are more likely to matter for mothers’ employment than government-supported leave, which lasts a few weeks or months.

According to Rachel Connelly and Jean Kimmel, the cost of childcare is a significant factor in single and married mothers’ decisions to seek work or apply for welfare.48 Kimmel finds “child-care prices significantly impede married mothers’ labor force participation behavior.”49

It has to be economically “worth it” for mothers to work, and regulations drive up the price of childcare. According to a study on regulation and the cost of childcare, “requiring [supervising daycare] teachers to have at least a high school diploma is associated with an increase in child care costs for infants of between 25 and 46 percent, or between $2,370 and $4,350 per year, per child.”50

Policymakers should eliminate regulation that artificially increases staff-to-child ratios or requires daycare teachers to hold a high school or college degree. Lawmakers should also reform labor laws to make work scheduling more flexible. Working parents, especially working mothers, highly value flexibility.

The 2017 Working Families Flexibility Act would allow interested employees to bank overtime compensation and use it as future time off. Government employees can do this, but private companies are prevented from compensating employees this way under the Fair Labor Standards Act, ostensibly to protect private-sector workers.51

These policies sidestep negative repercus-sions for women related to government-supported leave and also improve fairness, flexibility, and choice for working mothers and parents. Unlike government-supported leave, these reforms avoid creating another entitlement at a time when U.S. public debt is at its second highest level in history.52

In short, these policy improvements provide many of the promised benefits of government-supported leave, without the perverse consequences. These reforms should be considered instead by policymakers eager to improve workers’ lives.

Appendix A

Corporations increase paid leave offerings in early 2018 (all numbers in weeks)

|

Salaried workers |

Hourly workers/p> |

|||

|

Birth mother |

Other parent |

Birth mother |

Other parent |

|

|

IBM |

20 |

12 |

20 |

12 |

|

Starbucks |

18 |

12 |

6 |

6 |

|

Walmart |

16 |

6 |

16 |

6 |

|

Wells Fargo |

16 For primary parents, regardless of gender |

4 For nonprimary parents |

16 For primary parents, regardless of gender |

4 For nonprimary parents |

|

JP Morgan |

16 For primary parents, regardless of gender |

2 For nonprimary parents |

16 For primary parents, regardless of gender |

2 For nonprimary parents |

|

Amazon |

14 Includes 4 weeks prepartum |

6 |

14 |

6 Includes 4 weeks prepartum |

|

McDonald’s |

12 Also applies to some hourly corporate employees |

2 Adoptive primary caregivers receive more |

0 Depends on franchisee policies |

0 Depends on franchisee policies |

|

General Electric |

12 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

|

Kroger |

10 Also applies to nonunion hourly employees |

2 Also applies to nonunion hourly employees |

0–6 At two-thirds pay up to a max.; depends on collective bargaining agreements |

0 |

|

PepsiCo |

10 |

4 |

10 |

4 |

|

Target |

8 |

2 |

8 |

2 |

|

AT&T |

8 |

2 |

6–8 Depends on collective bargaining agreements |

0–2 Depends on collective bargaining agreements |

|

Cognizant Technology Solutions |

7 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

|

Walgreens |

6 100% pay |

0 |

6 2 weeks 100% pay, 4 weeks 50% pay |

0 |

|

Home Depot |

6 100% pay from company disability contributions |

0 |

6 60% pay from employee disability contributions |

0 |

|

Albertsons |

6 |

0 |

6 Depends on collective bargaining agreements |

0 |

|

TJX |

6 4 weeks 100% pay, 2 weeks 60% pay |

0 |

6 60% pay |

0 |

|

FedEx |

6 For FedEx Express, the largest operating company |

0 |

6 For FedEx Express, the largest operating company |

0 |

|

UPS |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Lowe’s |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Source: Claire Cain Miller, “Walmart and Now Starbucks: Why More Big Companies Are Offering Paid Family Leave,” New York Times, January 24, 2018.

APPENDIX B

Efficiency and redistributive effects of paid leave policies and related policies, national and international

|

Geography |

Policy |

Unintended consequences |

Sources and further reading |

|

International, OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries |

Parental leave and part-time work entitlements for women |

Encourage women’s part-time work and employment in lower level positions. |

Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, “Female Labor Supply: Why Is the US Falling Behind?,” NBER Working Paper no. 18702, 2013. |

|

United States (national) |

Unpaid Leave / FMLA (Family and Medical Leave Act) |

Women are 8% less likely to get promotions than they were before it became law. |

Mallika Thomas, “The Impact of Mandated Maternity Benefits on the Gender Differential in Promotions: Examining the Role of Adverse Selection,“ Institute for Compensation Studies, Cornell University, 2016, https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/ics/16/. |

|

California |

6-week subsidized paid leave |

Increased female unemployment by 5–22% and unemployment duration by 4–9%. |

Tirthatanmoy Das and Solomom W. Polachek (2014), “Unanticipated Effects of California’s Paid Family Leave Program,” discussion paper no. 8023, Institute for the Study of Labor, March 2014. |

|

Great Britain |

Job-protected leave expansions |

Fewer women holding management positions and other jobs with the potential for promotion. |

Jenna Stearns, “The Long-Run Effects of Wage Replacement and Job Protection: Evidence from Two Maternity Leave Reforms in Great Britain,” working paper, University of California, Davis, January 14, 2017, http://economics.ucdavis.edu/events/papers/28Stearns.pdf. |

|

Europe |

Paid care leave or lengthy paid leave |

These policies also are likely to reinforce the traditional division of care work in the home. |

Kimberly J. Morgan and Kathrin Zippel, “Paid to Care: The Origins and Effects of Care Leave Policies in Western Europe,” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 10, no. 1 (2003): 49–85. |

|

Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and United Kingdom |

Paid parental leave |

Reductions in women’s relative wages at extended durations. |

Christopher J. Ruhm, “The Economic Consequences of Parental Leave Mandates: Lessons from Europe,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 113, no. 1 (1998): 285–317, https://doi.org/10.1162/003355398555586. |

|

International |

Paid leave and longer paid leave |

Negatively affects employment rates and wages; long leave times reduce the likelihood that workers return to the same employer; career interruptions due to parental leave can lead to detachment from work and human capital depreciation, especially with longer leave durations. Evidence of discrimination against women and mothers in some areas of work exists; parental leave policies represent one potential explanatory factor. |

Astrid Kunze, “Parental Leave and Maternal Labor Supply,” Institute of Labor Economics, World of Labor, 2016, https://wol.iza.org/articles/parental-leave-and-maternal-labor-supply/long. |

|

Germany |

Five major expansions in maternity leave coverage |

Each expansion in leave coverage reduced mothers’ postbirth employment rates in the short run. |

Uta Schönberg and Johannes Ludsteck, “Expansions in Maternity Leave Coverage and Mothers’ Labor Market Outcomes after Childbirth” Journal of Labor Economics 32, no. 3 (2014): 469–505. |

|

Norway |

Expanding paid leave from 18 to 35 weeks (without changing the length of job protection) |

Regressively redistributed “primarily to middle and upper income families” and raised taxes considerably in a well-designed study. Expanding benefits had little impact on positive social outcomes including labor force participation in the short or long run, fertility, marriage, or divorce. |

Gordan B. Dahl et al., “What Is the Case for Paid Maternity Leave?,” NBER Working Paper no. 19595, October 2013, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19595. |

|

Illinois, New York, New Jersey |

Mandated maternity benefits |

Findings consistently suggest shifting of the costs of the mandates on the order of 100%. |

Jonathan Gruber, “The Incidence of Mandated Maternity Benefits,” American Economic Review 84, no. 3 (1994): 622–41. |

Source: Compiled by author from sources listed in table.

Notes

1 Government mandates use regulation to require businesses to pay for paid leave, whereas government subsidies use federal or state tax revenue to fund paid leave benefits.

2 Work & Family Policy Database, National Partnership for Women & Families, http://www.nationalpartnership.org/.

3 In 2017, Republicans also bolstered federal paid leave efforts by creating a tax credit program that provides $1 billion in tax credits annually to businesses providing paid leave. Additionally, in 2018 some conservatives advocated allowing workers to dip into Social Security benefits to cover paid leave.

4 Democrats have produced a proposal for government-paid leave called the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act (FAMILY Act), sponsored by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, FAMILY Act, S. 337, 115th Cong. (2017), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/337.

5 The difference between BLS and other national data sets and surveys is attributable to BLS’s peculiar survey methods, which require paid leave to exist separately from “sick leave, vacation, personal leave or short-term disability leave that is available to the employee.” This means that when employees take paid leave for family reasons, it doesn’t count if it could have been used for something else. Parents often save and pool paid personal leave, vacation, sick leave, and short-term disability in the event of a birth or adoption. On average, employees with five years of service are provided 22 days of sick and vacation leave alone. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Paid Leave in Private Industry over the Past 20 Years,” post by Robert W. Van Giezen, Beyond the Numbers 2, no. 18 (August 2013), https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-2/paid-leave-in-private-industry-over-the-past-20-years.htm. A majority of private-sector employees can carry over unused sick days from previous years, which adds to the tally. “Paid Leave Benefits, March 2016,” U.S. BLS, 2016, https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2016/benefits_tab.htm#tabs-4. Meanwhile, the median short-term disability benefit is 26 weeks for private-sector workers; 6 to 8 weeks can be used toward paid maternity leave. “Table 25. Short-term disability plans: Duration of benefits, private industry workers, March 2016,” U.S. BLS, 2016, https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2016/ownership/private/table25a.pdf. Unconventional benefit packages, like consolidated paid leave (or paid time-off banks) and unlimited paid leave plans allow employees to use paid leave for any reason, family or otherwise. Consolidated paid leave is on the rise; the BLS reports that 35 percent of private-sector employees receive it. In some industries, more than half of employees receive this flexible benefit. “Paid Leave Benefits, March 2016,” U.S. BLS, 2016, https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2016/benefits_tab.htm#tabs-4.l. Unlimited paid leave plans are also growing in certain industries. These plans allow employees to take as much leave as they want, whenever they want, assuming they meet performance expectations. These benefits can be used for parental reasons and they are paid. As Human Resources, Inc. puts it, “family-leave is usually created from a variety of benefits that include sick leave, vacation, holiday time, personal days, short-term disability.” What You Should Know about Maternity Leave, Short-Term Disability and the FMLA, Human Resources Inc, https://www.hri-online.com/blog/what-you-should-know-about-maternity-leave-short-term-disability-and-the-fmla. And although not all employers, especially small businesses, have official paid parental leave policies, “many employers are flexible and can work out an agreement with you.” Benefits that aren’t spelled out in the company manual are surely undercounted by the BLS, too. As a result, BLS figures grossly underestimate paid leave availability by ignoring employers’ flexible benefits. The BLS figure is an alarming-sounding outlier, not an accurate depiction of the typical experience of working parents.

6 The BLS figure and other federal data and national survey figures differ considerably. For example, the FMLA Worksite and Employee Survey’s figure is more than 40 percentage points higher than the BLS figure, and the National Survey of Working Mothers number is nearly 50 percentage points higher than the BLS figure.

7 The Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey number may be somewhat depressed because it is a 20-year average.

8 Disability benefits are paid and often can be used during pregnancy or postpartum. It appears that the difference in categorization results from disability benefits that are based on an employee’s contributions or an employer’s contributions to a disability plan. Disability benefits may have been included in paid or unpaid leave categories in previous survey years. A majority of growth in paid leave provision occurred prior to California implementing its first-in-the-nation family paid leave program in 2002.

9 Rachel Greszler and Drew Gonshorowski, “How a Proposed Federal Paid Family Leave Policy Would Become a Federal Entitlement and Weaken Social Security,” Heritage Foundation Policy Analysis no. 3318, May 29, 2018.

10 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employer Costs for Employee Compensation Archived News Releases,” BLS, Economic News Release, 2018, https://www.bls.gov/bls/news-release/ecec.htm#current.

11 Total wages in U.S. private industry in 2016 were $6.8 trillion, and assuming average employee compensation is an additional 32 percent greater after accounting for benefits, this gives us a total compensation of $8.98 trillion.

12 This is true whether federal paid leave is formulated as a mandate or a social insurance program financed through a payroll tax. Wage reductions in the face of benefit mandates occur because in markets, total worker compensation is determined in the long run by worker productivity. Businesses cannot pay workers more in compensation than their contribution to production.

13 Lawrence H. Summers, “Some Simple Economics of Mandated Benefits,” American Economic Review79, no. 2 (1989): 177–83.

14 Jonathan Gruber, “The Incidence of Mandated Maternity Benefits,”American Economic Review 84, no. 3 (1994): 622–41.

15 Countries include Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and United Kingdom. Christopher J. Ruhm, “The Economic Consequences of Parental Leave Mandates: Lessons from Europe,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 113, no. 1 (1998): 285–317.

16 Joya Misra, Michelle Budig, and Irene Böckmann, “Work-Family Policies and the Effects of Children on Women’s Employment and Earnings,” working paper no. 543, Luxembourg Income Study, 2010.

17 A socialized program may benefit some workers that expect to obtain more value from leave benefits than they expect to pay into the program.

18 These costs would likely be different depending on the industry and size of firm.

19 For instance, in Sweden only about 14 percent of men share paid leave equally with their partners, despite government subsidies providing bonuses and tax credits to encourage parents’ equal division of paid leave. Meanwhile, Danish men take just 10 percent of available paid leave. Christian W., “Danish Fathers Take Far Less Paternity Leave Than Nordic Brethren,” Copenhagen Post, November 3, 2017. The inequality in paid leave utilization likely occurs due to a variety of biological, sociological, and cultural factors. Women need time to recover from labor and delivery immediately following birth. Also, breastfeeding is a time-consuming undertaking.

20 Tirthatanmoy Das and Solomom W. Polachek, “Unanticipated Effects of California’s Paid Family Leave Program,” discussion paper no. 8023, Institute for the Study of Labor, March 2014.

21 Maya Rossin-Slater, “Maternity and Family Leave Policy,” NBER Working Paper no. 23069, January 2017.

22 Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, “Female Labor Supply: Why Is the U.S. Falling Behind?,” NBER Working Paper no. 18702, January 2013.

23 Jenna Stearns, “The Long-Run Effects of Wage Replacement and Job Protection: Evidence from Two Maternity Leave Reforms in Great Britain,” working paper, University of California, Davis, 2016, http://economics.ucdavis.edu/events/papers/28Stearns.pdf.

24 The glass ceiling is a metaphor for the firm but invisiblebarriers professional women face climbing the corporate ladder. Nabanita Datta Gupta, Nina Smith, and Mette Verner, “The Impact of Nordic Countries’ Family Friendly Policies on Employment, Wages, and Children,” Review of Economics of the Household 6, no. 1 (2008): 65–89.

25 Mallika Thomas, “The Impact of Mandated Maternity Benefits on the Gender Differential in Promotions: Examining the Role of Adverse Selection,” Institute for Compensation Studies, Cornell University, 2016, https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/ics/16/.

26 Economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn note that in non-U.S. OECD countries with paid leave, women are about half as likely as men to be managers, whereas women are approximately equally likely to be managers as men in the United States. Non-U.S. countries included in Blau and Kahn’s analysis include Australia, Austria, Denmark, France, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. In 2013, 16.9 percent of U.S. male workers were managers and 14.6 percent of U.S. female workers were managers. Blau and Kahn, “Female Labor Supply: Why Is the U.S. Falling Behind?”

27 The gap between the United States and Denmark or Sweden is larger yet, as shown in Figure 5.

28 William Scarborough, “What the Data Says about Women in Management between 1980 and 2010,” Harvard Business Review, February 23, 2018.

29 Jennifer L. Hook, “Gender Inequality in the Welfare State: Sex Segregation in Housework, 1965–2003,” American Journal of Sociology 115, no. 5 (2010): 1480–523.

30 Care leave policies differ from parental leave policies in that they are substantially longer (from 2–3 years, as compared with 3–12 months) and care leave benefits are paid at a flat rate instead of as a percentage of previous income. Kimberly J. Morgan and Kathrin Zippel, “Paid to Care: The Origins and Effects of Care Leave Policies in Western Europe,” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 10, no. 1 (2003): 49–85.

31 Nima Sanandaji, “The Nordic Glass Ceiling,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 835, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/nordic-glass-ceiling.

32 Charles L. Baum and Christopher J. Ruhm, “The Effects of Paid Family Leave in California on Labor Market Outcomes,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 35, no. 2 (2016).

33 Julia M. Goodman, “Did California’s Paid Family Leave Law Affect Mothers’ Time Spent on Work and Childcare?,” working paper, presented at Population Association of America 2012 Annual Meeting Program, hosted by Office of Population Research, Princeton University, 2012, http://paa2012.princeton.edu/abstracts/120449.

34 Challenging conventional socio-cultural expectations and pressures is difficult. For example, a recent study shows that a full two-thirds of Harvard-educated millennial-generation men expect their partners to handle the majority of childcare. And women are more likely than men to make decisions “to accommodate family responsibilities, such as limiting (work-related) travel, choosing a more flexible job, slowing down the pace of one’s career, making a lateral move, leaving a job, or declining to work toward a promotion.” Harvard Business Review; “Rethink What You ‘Know’ about High-Achieving Women,” post by Robin J. Ely, Pamela Stone, and Colleen Ammerman, December 2014. Families may shift away from the traditional division of household labor, given women’s greater workforce participation and educational success, but government shouldn’t have a thumb on the scale or inadvertently impede that readjustment, which should be up to families to decide.

35 Private paid leave may differentially affect employees within a firm (for example, those with vs. those without children), but those effects may be mitigated by other aspects of compensation or work schedules or promotions. Moreover, this is a private issue.

36 This is likely under either government-subsidized or -mandated leave. The share of U.S. adults that are childless is significant. Fifteen percent of women between the ages of 40 and 44 were childless in 2014. Twenty-two percent of women between ages 40 and 44 with at least a master’s degree were childless in 2015, despite the number falling over previous decades. Gretchen Livingston, “Childlessness Falls, Family Size Grows among Highly Educated Women,” Pew Research Center, May 7, 2015, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/05/07/childlessness-falls-family-size-grows-among-highly-educated-women/.

37 Gordon B. Dahl et al., “What Is the Case for Paid Maternity Leave?,” NBER Working Paper no. 19595, October 2013.

38 “Fertility of Men and Women Aged 15–44 Years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006–2010,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 12, 2012; Christian W., “Danish Fathers Take Far Less Paternity Leave Than Nordic Brethren”; and Livingston, “Childlessness Falls, Family Size Grows among Highly Educated Women.”

39 As noted elsewhere, in Sweden only 14 percent of men share paid leave equally with their partners. Danish men take 10 percent of available paid leave and men account for 4 percent of paid leave beneficiaries in Austria and France. Christian W., “Danish Fathers Take Far Less Paternity Leave Than Nordic Brethren”; and “Parental Leave: Where Are the Fathers?,” OECD Policy Brief, March 2016, https://www.oecd.org/policy-briefs/parental-leave-where-are-the-fathers.pdf.

40 “The Rise in Dual Income Households,” Pew Research Center, June 18, 2015, http://www.pewresearch.org/ft_dual-income-households-1960-2012-2/.

41 Ariel Pihl and Gaetano Basso,“Paid Family Leave, Job Protection and Low Take-Up among Low-Wage Workers,” University of California, Davis, Center for Poverty Research Policy Brief 3, no. 12, http://poverty.ucdavis.edu/sites/main/files/file-attachments/cpr-pihl_basso_pfl_brief.pdf.

42 Dahl et al., “What Is the Case for Paid Maternity Leave?”

43 The adjusted gender pay gap should be zero, when all relevant variables are accounted for. Most studies and the public debate focus on the unadjusted pay gap, rather than the adjusted pay gap. The gender pay gap is a particularly unhelpful statistic. It compares two values that aren’t comparable: median men’s and women’s wages. The pay gap looks large because (1) the median man and woman work in different industries with varying levels of profitability, and (2) the median man and woman make different family, career, and lifestyle tradeoffs. Most of the gender pay gap in the United States can be explained by characteristics including industry, role, location, education, and experience. Andrew Chamberlain, “Demystifying the Gender Pay Gap: Evidence from Glassdoor Salary Data,” Glassdoor Research Report, March 2016, https://www.glassdoor.com/research/studies/gender-pay-gap/.

44 Uta Schönberg and Johannes Ludsteck, “Expansions in Maternity Leave Coverage and Mothers’ Labor Market Outcomes after Childbirth,” Journal of Labor Economics 32, no. 3 (2014): 469–505.

45 Blau and Kahn, “Female Labor Supply: Why Is the U.S. Falling Behind?”

46 Henrik Kleven, Camille Landais, and Jakob Egholt Søgaard, “Children and Gender Inequality: Evidence from Denmark,” NBER Working Paper no. 24219, January 2018.

47 Hadas Mandel and Moshe Semyonov, “Family Policies, Wage Structures, and Gender Gaps: Sources of Earnings Inequality in 20 Countries,” American Sociological Review 70, no. 6 (2005): 949–67, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4145401; and Giuseppe Bertola, Francine D. Blau, and Lawrence M. Kahn, “Labor Market Institutions and Demographic Employment Patterns,” NBER Working Paper no. 9043, July 2002.

48 Rachel Connelly and Jean Kimmel, “The Effect of Child Care Costs on the Employment and Welfare Recipiency of Single Mothers,” Southern Economic Journal 69, no. 3 (2003): 498–519, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1061691.

49 Jean Kimmel, “Child Care Costs as a Barrier to Employment for Single and Married Mothers,” Review of Economics and Statistics 80, no. 2 (1998): 287–99.

50 Diana W. Thomas and Devon Gorry, “Regulation and the Cost of Child Care,” Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center, George Mason University, 2015, https://www.mercatus.org/publication/regulation-and-cost-child-care.

51 Working Families Flexibility Act of 2017 (H.R. 1180): Hearing before the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections, Committee on Education and the Workforce, U.S. House of Representatives, 115th Cong., 1st sess., April 5, 2017.

52 As measured as a percentage of GDP in 2018. Congressional Budget Office, “The 2018 Long-Term Budget Outlook,” June 2018, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/53919.