Legislation calling for the establishment of a Centennial Monetary Commission “to examine the United States monetary policy, evaluate alternative monetary regimes, and recommend a course for monetary policy going forward,” was introduced in both the House and the Senate in July 2015, with the essential provisions of the bill passing the House in November. The plan draws inspiration from the National Monetary Commission convened over a century ago, in response to the Panic of 1907.

This Policy Analysis reviews the earlier Monetary Commission’s origins, organization, and shortcomings, in order to suggest how a new commission might improve upon it. In contrast to more conventional, celebratory accounts of the Fed’s establishment, it finds that, instead of serving as a means for achieving desirable reforms, the National Monetary Commission served as a façade behind which its chair, Sen. Nelson Aldrich (R‑RI), pursued a personal monetary reform agenda heavily influenced by major New York bankers.

The resulting “Aldrich Plan” sought to preserve New York banks’ dominant position in the financial system, even though doing so meant setting aside alternative reform proposals that sought to address the root cause of crises, including plans that would have introduced nationwide branch banking while removing Civil War–era limitations on banks’ ability to issue circulating banknotes. Although the Aldrich Plan itself failed, many of its features, including those catering to the interests of the big New York banks, made their way into the later Federal Reserve Act.

Not surprisingly, that Act proved more effective in preserving New York’s financial hegemony than in securing financial stability. If the Centennial Monetary Commission is to prove more successful than its predecessor in serving as a means for achieving financial stability, it must be a genuine, bipartisan commission, with open proceedings, and free of the taint of special-interest influence, which today means not only the influence of Wall Street, but also that of the Federal Reserve establishment itself.

Introduction

Legislation calling for the establishment of a Centennial Monetary Commission “to examine the United States monetary policy, evaluate alternative monetary regimes, and recommend a course for monetary policy going forward,” was introduced in both the House and the Senate in July 2015, with the essential provisions of the bill passing the House in November.1 The Commission is to consist of 12 voting members (8 Republicans and 4 Democrats, given the existing majority and minority compositions), together with two nonvoting members: one chosen by the Secretary of the Treasury, and the other, consisting of a Federal Reserve Bank president, chosen by the Fed chair.

According to Rep. Kevin Brady (R‑TX), the measure’s original sponsor, the Commission is to consider “all points of view… with respect to the proper role envisioned for our central bank.”2 Should the present version of the law pass, the Commission’s report would be due by December 1, 2016.

Prompted by the subprime financial crisis, and particularly by a belief that the crisis revealed significant shortcomings of the Federal Reserve System, the Centennial Monetary Commission plan draws inspiration from the National Monetary Commission convened over a century ago, in response to the Panic of 1907.3 It was, perhaps somewhat ironically, mainly owing to the efforts of that earlier commission, which was also charged with studying alternatives to, and proposing a plan for reforming, the then-existing U.S. monetary system, that the Federal Reserve Act itself was passed.

In this Policy Analysis I review the original Monetary Commission’s origins, organization, and achievements. I mainly wish to identify that Commission’s shortcomings, with the aim of offering some advice concerning how a new commission might improve upon it. But I also wish to respond to conventional, celebratory accounts of the Fed’s establishment by drawing attention to the way in which special interests, and representatives of the major New York City banks in particular, seized control of the pre-Fed currency reform movement, taking it in a direction better suited to preserving and enhancing Wall Street’s profits than to ending financial crises.

I begin by reviewing the financial crises that first gave rise to a movement for monetary reform, and the progress of that movement up to the passage of the Aldrich-Vreeland Act in 1908, by which the National Monetary Commission was established. I then show how the Commission became a façade behind which its chair, Sen. Nelson Aldrich (R‑RI), pursued a personal monetary reform agenda heavily influenced by major New York bankers. I show how the Commission’s successful public relations campaign overcame resistance to the measures Aldrich and his advisers favored, including a “National Reserve Association,” to the point of compelling the Democrats to include similar provisions in their alternative to the Aldrich plan, which became the Federal Reserve Act. I show that the Fed was, in fact, more effective in preserving New York’s financial hegemony than in securing financial stability. Finally, I draw from this review of history some lessons concerning how a new monetary commission might replicate the earlier commission’s strengths, while avoiding its flaws.

Financial Crises under the National Currency System

The National Monetary Commission was an outgrowth of crises that beset the pre–Federal Reserve monetary system. A review of those crises and the circumstances that gave rise to them is therefore essential to a proper understanding of that Commission’s origins and purpose.

During the last decades of the 19th century, and the first decade of the 20th, the cost of credit in the United States tended to vary with the seasons, especially by rising every autumn as farmers drew on banks for funds with which to “move the crops.” The seasonal tightening was largely a reflection of the fact that moving the crops meant paying migrant workers, who had to be paid in cash. When farmers asked their banks for cash, national banks, despite being authorized to issue their own, in the form of circulating banknotes, tended to draw instead on their reserves, sometimes by withdrawing funds from their city correspondents. Unless they were located in New York, the correspondent banks in turn withdrew funds from their own correspondents in that city. To avoid having their reserves fall below legal requirements, correspondent banks everywhere, but New York banks especially, cut back on lending until the harvest season ended and withdrawn cash gradually found its way back into the banking system.

In most years tightening of credit was the whole story. But in others mere tightening gave way to panic. Between the end of the Civil War and 1913, the United States endured five major financial crises: in 1873, 1884, 1890, 1893, and 1907. With the exception of the 1884 panic, which broke out in May, the crises all took place during the fall harvest; and all, with the exception of the 1893 panic, were triggered by the failure of some important firm or firms, often (though not always) located in New York. The failures led to further tightening of the New York money market, including the market for “call” money used to finance stock purchases, and thence to falling stock prices. Falling stock prices in turn aggravated New York banks’ usual seasonal liquidity problems by making it impossible for them to recall many of their loans, and by triggering suspensions of payment, sometimes in New York only, and sometimes nationwide. On several occasions, suspensions were avoided only because Leslie Shaw, Secretary of the Treasury from 1902 to 1907, averted them by shifting cash from the Treasury’s coffers to various national banks in anticipation of the harvest-time drain, and took it back again afterwards.4

That the crises tended to get worse over time was particularly disturbing. The Panic of 1893 was more serious than that of 1884; while the Panic of 1907 was the most severe of all. Senator Aldrich, who was to play the central part in organizing and leading the National Monetary Commission, described that last crisis as follows:

Suddenly the banks of the country suspended payment, and acknowledged their inability to meet their current obligations on demand. The results of this suspension were felt at once; it became impossible in many cases to secure funds or credit to move the crops or to carry on ordinary business operations; a complete disruption of domestic exchange took place; disorganization and financial embarrassment affected seriously every industry; thousands of men were thrown out of employment, and wages of the employed were reduced. The men engaged in legitimate business and the management of industrial enterprises and the wage-earners throughout the country, who were in no sense responsible for the crisis, were the greatest sufferers.5

The Role of Regulation

Frequent financial crises were, by the last decades of the 19th century, mainly a U.S. phenomenon. No other relatively developed nation suffered from them. What set the United States apart?

During the late 1800s the United States, like most advanced industrial nations, operated on a gold standard, which meant that its money consisted either of actual gold coins or of paper currency and deposits redeemable in such coins.6 The United States also made use of paper currency. Until the Civil War, such currency consisted solely of the circulating notes of numerous state-authorized banks. The outbreak of the war led to legislation authorizing the Treasury to issue its own paper money, known officially as United States Notes and, unofficially, as “greenbacks.” A subsequent suspension of gold payments placed the nation on a greenback standard.

Wartime legislation also provided for the establishment, by the federal government, of national currency-issuing banks, while subjecting state banks to a prohibitive 10 percent tax on their outstanding notes so as to compel them to switch to national charters.7 Consequently, when gold payments were resumed in 1879, the stock of U.S. paper currency consisted entirely of greenbacks, the quantity of which was absolutely fixed, and of national banknotes.

Although several foreign nations, including England, France, and Germany, had by this time established paper currency monopolies, the United States was hardly unique in allowing numerous banks to issue paper money. On the contrary: until well into the 20th century, competitive or “plural” note-issue systems were the rule rather than the exception.8 What set the United States apart were destabilizing financial regulations peculiar to it. Two sorts of regulations were especially at fault. The first allowed national banknotes to be issued only to the extent that they were fully backed by government securities. Indeed, until 1900 the requirement was that for every $90 of their notes outstanding, the banks had to have surrendered to the Comptroller of the Currency authorized bonds having a face value of at least $100.

This bond-deposit requirement caused the supply of national banknotes to vary, not with the public’s changing currency needs, but with the availability and price of the requisite bonds. The requirement’s presence within the National Currency and National Bank acts of 1863 and 1864 reflected those measures’ original purpose of helping the Union government to finance its part in the Civil War.

During the last decades of the 19th century, the government, instead of being desperate for funds, ran frequent budget surpluses, which it chose to apply toward reducing the federal debt. As it did so, bonds bearing the banknote circulation privilege became increasingly scarce, and national banks, instead of trying to put more notes into circulation as the economy grew, did just the opposite, retiring their notes so as to be able to sell and realize gains on the bonds that had been backing them. Between 1881 and 1890, a period of general business expansion and rapid population growth, the outstanding stock of national banknotes shrank from over $320 million to just under $123 million! Because the quantity of greenbacks, the nation’s only other paper currency, was fixed by statute, the total money stock was no more elastic than national banknotes were. National banks were especially unwilling to acquire and hold costly bonds just for the sake of meeting temporary currency needs, such as those of the harvest season, because doing that meant having stacks of notes resting idle in their vaults for much of the year, and incurring correspondingly high opportunity costs.

The other important source of U.S. financial instability consisted of laws and other stipulations that prevented many U.S. banks, including all national banks,from establishing branches away from their home office. Besides improving banks’ ability to geographically diversify their assets and liabilities, branching would have allowed them to shift funds to and from different markets, in response to shifting patterns of demand, while still retaining complete control of those funds.

An early source of opposition to branching—state authorities’ narrow construal of rights conferred by banks’ charters—was subsequently reinforced, according to O. M. W. Sprague, by “[p]rejudices aroused in the course of Jackson’s war against the Second Bank of the United States; a somewhat absurd fear of an impossible monopoly in banking; and the self-regarding interests of [established] local bankers.”9 Even despite such prejudices, branch banking flourished prior to the Civil War in some parts of the South and Midwest. It was only after the passage of the national banking acts and 10 percent tax on state banknotes (the last of which came close to wiping out all state banks) that “unit” banking “became a distinguishing feature of the United States economy.”10

National banks were themselves unable to branch, not owing to any specific provisions of the national banking laws, but to the way in which those laws were interpreted. This fact must be kept in mind in light of frequent claims that unit banking was either an inevitable or an unalterable feature of the pre-Fed U.S. economy. According to Richard McCulley,

[N]o evidence exists that the framers of the 1863 and 1864 legislation meant to preclude branch banking. Nevertheless Hugh McCulloch, the first comptroller of the currency, and succeeding comptrollers, interpreted two clauses in the National Banking Act to prohibit branch banking. The act required persons forming an association to specify “the place” where they would conduct banking and required that the transaction of usual business be “an office or banking house” located in the city specified in the charter. Thus the administration of the National Banking Act further directed American banking toward a unit structure and prevented the development of large banks with branches, a system more typical of modern economies.11

More than any other factor, unit banking made the U.S. economy vulnerable to panics. It limited banks’ opportunities for diversifying their assets and liabilities. It made coordinated responses to panics more difficult. Finally, it forced banks to rely heavily on correspondent banks for out-of-town collections, and to maintain balances with them for that purpose. Correspondent banking, in turn, contributed to the “pyramiding” of bank reserves: country banks kept interest-bearing accounts with Midwestern city correspondents, sending their surplus funds there during the off season. Midwestern city correspondents, in turn, kept funds with New York correspondents, and especially with the handful of banks that dominated New York’s money market. Those banks, finally, lent the money they received from interior banks to stockbrokers at call.12

The pyramiding of reserves was further encouraged by the National Bank Act, which allowed national banks to use correspondent balances to meet a portion of their legal reserve requirements. Until 1887, the law allowed “country” national banks—those located in rural areas and in towns and smaller cities—to keep three-fifths of their 15 percent reserve requirement in the form of balances with correspondents or “agents” in any of fifteen designated “reserve cities,” while allowing banks in those cities to keep half of their 25 percent requirement in banks at the “central reserve city” of New York. In 1887 St. Louis and Chicago were also classified as central reserve cities. Thanks to this arrangement, a single dollar of legal tender held by a New York bank might be reckoned as legal reserves, not just by that bank, but by several; and a spike in the rural demand for currency might find all banks scrambling at once, like players in a game of musical chairs, for legal tender that wasn’t there to be had, playing havoc in the process with the New York stock market, as banks serving that market attempted to call in their loans.13

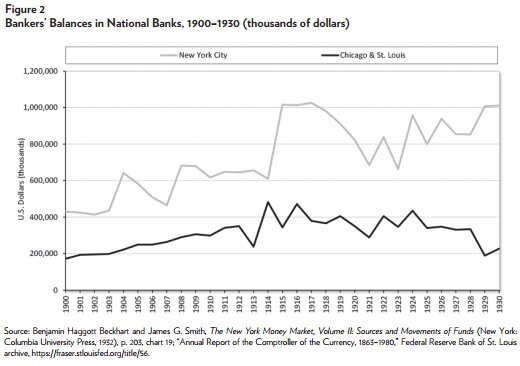

The financial condition of half a dozen New York banks thus became “the most important single factor to be considered in estimating the strength of the system as a whole.”14 “In a dramatic way,” Benjamin Beckhart and James Smith observe in their 1932 volume on the New York money market, “the panic of 1907 demonstrated the evils inherent in the concentration of reserve funds in New York City.” They continue:

The social peril of a dominating financial center and the alleged withdrawal of funds from the farming West for speculation in the East furnished fuel for constantly burning issues. It would probably be no exaggeration to say that this problem in itself was sufficient to give impetus to the banking reform movement which eventually resulted in the establishment of the Federal Reserve system.15

Nationwide branch banking, by permitting one and the same bank to operate both in the countryside and in New York, would have avoided this dependence of the entire system on a handful of New York banks, as well as the periodic scramble for legal tender and ensuing market turmoil. As Sprague explains,

The bank with many branches can concentrate its reserves wherever the demand arises. In a measure this is true in the United States at present, under the system of bankers’ deposits in reserve cities; but the transfer of cash would be more immediate and automatic under a branch system. Moreover, the existing system is exceedingly unsatisfactory during periods of acute distress… . [E]xperience shows that at such times country banks withdraw deposits to protect themselves, even when they are in no immediate danger. The credit structure as a whole is weakened, reserves become unavailable at points of greatest danger, and banks fail which might have survived with a little timely assistance.16

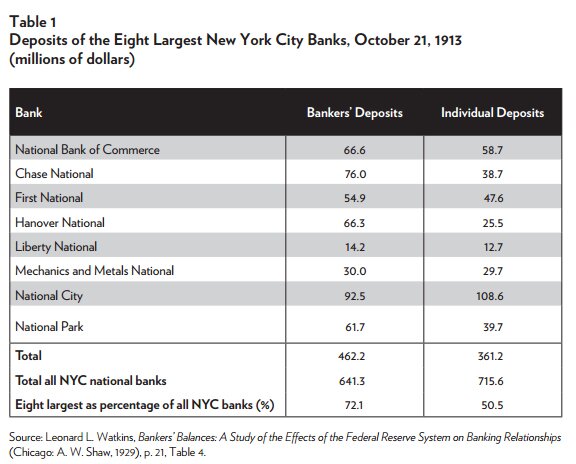

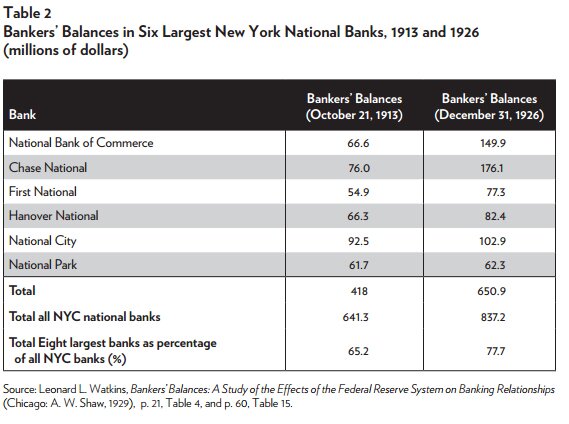

Although it exposed them to occasional crises, the correspondent business was both very lucrative to the most powerful New York banks and crucial to their success, having come to surpass in importance the business they did with individual depositors. By October 1913, the eight largest New York banks collectively managed $462.2 million in bankers’ balances, as opposed to just $361 million in individual deposits (See Table 1). It was owing to those banks’ concern to preserve their correspondent banking business that they came to play a prominent part in shaping the course of subsequent banking and currency reform efforts.

The Asset Currency Movement

In light of existing regulations’ contribution to U.S. monetary instability, it was only natural for those seeking to improve the U.S. banking and currency system to recommend getting rid of, or at least substantially relaxing, the troublesome regulations. In particular, they favored letting national banks issue notes backed by their general assets—that is, by the same general assets those banks held against their deposits. Some also favored doing away with the prohibitive tax on state banknotes.

Although some early calls for “asset currency” predate the Panic of 1893, the movement first achieved prominence in the wake of that crisis, when “the business and financial community was nearly unanimous in its desire to abolish bond-secured currency and issue a new national bank note secured by the [general] assets of the issuing banks.”17 “The appeal of an asset-based currency,” Elmus Wicker notes, “resided in its simplicity. It did not require further intrusion by government into the banking industry. No major institutional changes were necessary.”18

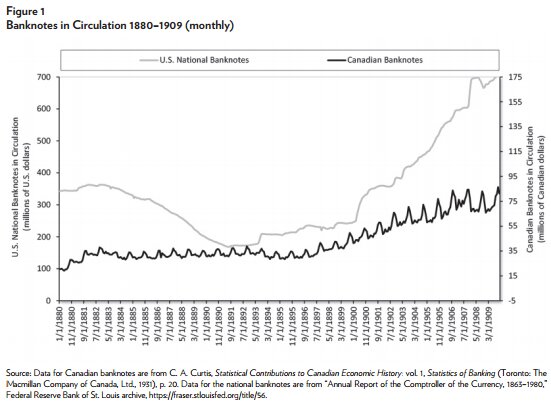

The asset currency movement drew inspiration from several nations that had long relied on asset-backed currency, and especially from Canada, where several dozen banks supplied such currency while managing more than one thousand branch offices scattered across the country. Although it involved practically no government regulation save certain minimum capital requirements, Canada’s system managed to accommodate fluctuating currency needs without difficulty and without any losses to the public. “As surely and regularly as the autumn months come around and the inevitable accompanying demand for additional currency begins to manifest itself,” wrote L. Carroll Root, so “does the currency of the banks automatically respond.”19 Credit crunches and panics were unknown. As one prominent Canadian banker put it, “The Canadians never know what it is to go through an American money squeeze in the autumn.”20 The stark contrast between the behavior of the currency stock in the United States and its behavior in Canada is shown in Figure 1.

Proposals to eliminate or relax regulatory restrictions on banks’ ability to issue notes had as their counterpart provisions that would allow banks to branch freely. The Canadian system supplied inspiration here as well. Canadian banks enjoyed, and generally took full advantage of, nationwide branching privileges. What’s more, by an ironic twist, many also had branches in New York City, and so had direct access to a valuable market that was denied to most of their U.S. counterparts.

Many asset currency proposals called upon the Comptroller of the Currency to allow national banks to branch, while also requiring banks to redeem their notes—that is, to exchange them, on demand, for gold or greenbacks—at their branches as well as at their head offices, both as an alternative to correspondent banking (and the consequent pyramiding of reserves) and as the most straightforward means for absorbing redundant banknotes: unlike unit banks, banks with nationwide branch networks could resort to local exchanges or “clearings” of notes and checks as a less costly and more expeditious alternative to shipping them to one or more central clearinghouses or redemption agencies. Besides aiding the prompt mopping-up of excess currency, and reducing interior banks’ reliance upon city correspondents, branch banking would also enhance banks’ safety through greater diversification of bank assets and liabilities. For these reasons pleas for branch banking quickly became “an integral part” of the asset currency movement.21

Despite the emphasis they placed on deregulation, asset currency plans often called upon either banks or the government to take various positive steps, many of which were aimed at assuaging critics’ fears that asset currency might be less secure than bond-backed notes, or that banks might overissue it. To protect noteholders from losses due to bank failures, most plans provided for a banknote “safety” or “guarantee” fund, typically to be kept equal to 5 percent of the total value of asset-backed notes. To guarantee that excess notes would be redeemed promptly, even in the absence of widespread bank branches, many also called for the establishment of banknote redemption facilities in major commercial centers across the country. Like other asset currency measures, such proposals looked to Canada for inspiration, for Canadian banks also took part in a banknote guarantee fund, while being required to provide for the redemption of their notes in each of Canada’s seven provinces.

More than a dozen asset currency bills found their way into Congress between the Panic of 1893 and the Panic of 1907. Until 1897, the most important of these, and the basis for many later proposals, was the Baltimore Plan, so-called because it originated in an 1894 meeting of Baltimore’s bankers. During the mid-1890s the movement was sidelined when its more active participants went to battle against “Free Silver.”22 But with William McKinley’s election victory it sprang back to life.

Of various McKinley-era asset currency plans, the most important by far was that which grew out of the Indianapolis Monetary Convention, where 300 businessmen-delegates, representing more than 100 cities, resolved to convince Congress to appoint a Monetary Commission, and, if that effort failed, to establish an eleven-member commission of their own. Although McKinley himself favored a government-sponsored commission, and the House passed a bill to establish it, the Senate, led by Aldrich, rejected the plan.23 Consequently the Indianapolis Monetary Commission itself, a private and nonpartisan body that was a sort of prototype for the later National Monetary Commission, took up the challenge of developing a reform proposal. The Commission’s impressive 600-page report, including its proposed currency and banking reform, was published and offered to Congress in January 1898.24 The report would remain the most comprehensive of all arguments in favor of asset currency.

J. Laurence Laughlin, a University of Chicago economics professor, was the most important of the Indianapolis Monetary Commission’s 11 members, and the uncredited author of its report. He had criticized some earlier asset currency plans, and the Baltimore Plan in particular, for failing to provide adequately for the active redemption of national banknotes, by means of branch banking or otherwise.25 Laughlin would remain a key figure in the currency reform movement until the passage of the Federal Reserve Act, to which he also contributed. However, in 1898 Laughlin stood so squarely in the asset currency camp that his report contained only one passing reference to a “central bank.” As Roger Lowenstein notes, the Indianapolis delegates whose views Laughlin represented “were headed in the other direction—they wanted the government out of banking.”26

Despite the Indianapolis Commission’s impressive report, Congress rejected its asset currency plan and various bills inspired by it.27 Instead, with the Gold Standard Act of March 14, 1900, Congress put into effect those parts of the Indianapolis proposal addressing the question of the standard, while making it somewhat easier for national banks to issue bond-backed notes. It allowed national banks to issue notes up to deposited bonds’ par value, rather than 90 percent of that value; and it cut the tax on outstanding notes in half. Most importantly, it provided for conversion of expensive bonds that were about to mature into others running 30 years and paying a lower rate.28

Although the Gold Standard Act reversed the downward movement in the stock of national banknotes, the relief this brought didn’t last long: in the fall of 1901, credit tightened again, as New York “experienced the greatest difficulty meeting the autumnal call from the interior,” reminding everyone that another crisis would come sooner or later.29

By then, asset currency had gained a new and influential advocate in Charles N. Fowler, a Republican Congressman from New Jersey, and Congress’s “most persistent and articulate champion of financial reform.”30 Fowler had been made chair of the House Committee on Banking and Currency when Teddy Roosevelt took office the previous March. Between 1902 and 1907, he introduced several asset currency bills, all of which were endorsed by the American Bankers Association (ABA) and various chambers of commerce.31 But despite this support, and his considerable status, Fowler’s attempts fared no better than other asset currency proposals had. Although several were reported favorably in the House, they died when the Senate Banking Committee refused to take them up.

Opponents of Asset Currency

Despite its popularity among experts, and the persuasive evidence that Canadian experience supplied, the asset currency movement faced stiff opposition both within the government and from representatives of the banking industry.

The banking industry’s attitude toward asset currency is best grasped by referring to Richard T. McCulley’s treatment of the late-19th century politics of banking reform as a struggle among three banking industry interest groups: Wall Street, Main Street, and LaSalle Street.32 The last, meaning the bankers of Chicago but also those of other relatively large Midwestern cities, spearheaded the asset currency movement, hoping by means of it “to improve their competitive position vis-á-vis the East, and to expand at the expense of smaller rural bankers.”33 Country or “Main Street” bankers were, on the other hand, generally opposed to branch banking, fearing, as one of them put it in assessing Fowler’s 1902 plan, that the major banks of the great money centers “would be able to plant their branches in every city or town where they pleased, and ... would soon drive the local institutions out of business.”34 A 1903 resolution of bankers of Kansas and Nebraska went still further, condemning branch banking, not only as “tending to establish a monopoly ... in the hands of a few millionaires,” but also as “unpatriotic, un-American, unbusinesslike.”35

Because plans calling for it were often joined by calls for letting banks branch, in the eyes of country bankers asset currency became “blackened by the company it kept.”36 According to H. Parker Willis, writing at the end of 1903,

when the question of bond security has come up in Congress, the influence of small banks has been thrown forcibly against any change, and the general apathy of members, coupled perhaps with a feeling that the matter was a good one for use as the basis in political huckstering, has tended to keep things in status quo.37

Small bankers’ tendency to assume that “complicated reforms … always originated with the ‘sinners’ and ‘plutocratic combinations’ in Wall Street,” was only part of the problem.38 “Strangely enough,” Louis Ehrich (a prominent Colorado businessmen and asset currency proponent) remarked at a 1903 dinner at New York’s Reform Club, “the primal hindrance to a reform of the currency has been the indifference, and even opposition, of this very banking class, this so-called Money Power.”39

In fact there was nothing at all surprising about the Money Power’s unwillingness to join the movement for asset currency. Far from being uninterested in the course of reform, the major New York banks, which by 1900 had come to specialize in investment rather than commercial banking, were determined to oppose any proposal that threatened to undermine their lucrative correspondence-banking business.40 By the time of the 1907 Panic, New York banks collectively held about 35 percent of all correspondent balances, amounting to about $500 million. Eighty percent of this amount was held by the city’s “big six” national banks, including the National City Bank, the National Bank of Commerce, and the First National Bank.41 Thus it happened that Main Street unwittingly joined forces with Wall Street, whose machinations it most feared, with both battling against the LaSalle Street–led asset currency campaign.42

Banking-industry opposition to asset currency had as its counterpart the opposition of two powerful politicians, politically as far removed from one another as Main Street and Wall Street. The first of these was William Jennings Bryan.

Though better known for having campaigned for free silver and against a gold standard, Bryan was no less opposed to commercial banknote currency, his belief being that government alone should issue paper money. As a Democratic congressman (1891–95), Bryan consistently opposed measures calling for asset currency, as well as attempts to repeal the 10 percent tax on state banknotes. When President Grover Cleveland urged that the prohibitive tax be removed in the wake of the Panic of 1893, Bryan “delivered an impassioned speech” in which he not only opposed that step but expressed his desire to see all national banknotes retired in favor of government money.43

Although he lost his presidential bids both in 1896 and in 1900, Bryan maintained control of the powerful, progressive minority within the Democratic Party. “If you said anything against Bryan,” a Democratic representative of long standing recalled many years later, “you got knocked over, that is all.”44 Using this influence Bryan waged “incessant war against asset currency,” treating it, without warrant, as part of a conspiracy of major financiers to assert control over the nation’s money supply.45

During the Panic of 1907, Bryan, far from moderating his blanket opposition to any relaxation of existing currency laws, insisted on it all the more vehemently. In response to the many “editorials in the city dailies, demanding an asset currency,” Bryan claimed that the panic was itself “a part of the plutocracy’s plan to increase its hold upon the government.”46 “The big financiers,” he wrote, “have either brought on the present stringency to compel the government to authorize an asset currency or they have promptly taken advantage of the panic to urge the scheme which they have had in mind for years.” It followed, Bryan argued, that Democrats were “duty bound to … oppose asset currency in whatever form it may appear.” Democrats, he said,

should be on their guard and resist this concerted demand for an asset currency. It would simply increase Wall Street’s control over the nation’s finances, and that control is tyrannical enough now. Such elasticity as is necessary should be controlled by the government and not by the banks.47

The other major political opponent of asset currency could not have been less like Bryan in every other respect. Nelson Aldrich was a wealthy, blue-blooded Republican, who served on the Senate Finance Committee for 30 years and chaired it from 1898 to 1911. He was for that reason alone by far the most powerful shaper of monetary policy and reform during that time. According to McCulley, “Aldrich was at the same time the most logical and the least promising figure to lead the reform of American banking.”48 The very “embodiment of the Republican congressional ‘Old Guard,’” he was notorious for his role in “shielding eastern banking and corporate interests from greater public accountability and government control.”49 Until the 1907 panic, Aldrich employed his power, not to encourage monetary reform, but to stand in its way, especially by foiling every plan for asset currency.50

Fowler’s asset currency bills became particular targets of Aldrich-led opposition. According to Willis, who assisted in drafting the Indianapolis Commission Plan, and who would later assist Carter Glass in drafting the Federal Reserve Act, Fowler’s first, 1902 asset currency bill was scuttled by a Republican caucus:

The whole tone of the caucus … was one of contempt for the movement to gain a currency not based on bonds… . The outcome was a crushing defeat for the original Fowler measure and therewith for credit currency—a defeat which was only deepened by the slightly less contemptuous but still very hostile attitude of the Republicans toward the revised and simplified Fowler bill which appeared … at the next session of Congress.51

Although President Roosevelt had been prepared to support Fowler’s 1903 attempt, Aldrich refused to cooperate. “Our currency,” he told A. Barton Hepburn, one of the plan’s proponents, “is as good as gold. Why not let it alone?”52 To more effectively counter Fowler’s attempt, the big New York bankers first denounced it as one that would give rise to “second-class currency.” They then arranged to have Aldrich introduce an alternative “proposing a limited expansion of the currency with notes issued against selected state, municipal, and railroad bonds”—that is, with bonds of the very sort that had been the basis of the notoriously “second-class” currencies and “wildcat” banking of the antebellum era.53

Aldrich was, however, more concerned with making his bill attractive to his fellow Republican senators, and the special interests they represented, than with keeping the nation’s currency safe. As Paul Warburg, who played a major part in shaping subsequent reforms, put it, Aldrich “believed in bond-secured currency and, at a pinch, in still more bond-secured currency.”54 Wrote Willis:

It was natural that the conservative banking interests should be attracted by the Aldrich bill and repelled by the Fowler bill, partly because the Aldrich bill proposed no radical changes, partly because it promised to enhance the price of certain existing securities. The Fowler bill took a step in the direction of greater freedom of competition in banking … while it possibly squinted toward the ultimate introduction of a branch banking measure, though this, of course, would be entirely a matter for the future.55

Democratic filibustering ultimately prevented a Senate vote on the Aldrich bill. In the meantime, the measure’s Republican supporters attempted to bypass Fowler’s committee, which also would have put paid to it, by having a similar bill introduced in the House as a revenue measure, with the intent of having it reported to the Ways and Means Committee.56 Fowler protested, and the House Speaker sustained him, so Aldrich’s bill would have died anyway. Still, the episode illustrates the lengths to which Aldrich and the rest of the Republican Old Guard were prepared to go to counter any threat to the monetary status quo.

In December 1906, Fowler tried again, introducing legislation embodying a new asset currency plan developed during the preceding months by the ABA’s Currency Commission. The plan would have allowed national banks to issue asset-backed notes up to 25 percent of their capital, or 40 percent of their outstanding bond-secured notes (depending on which limit was lower) subject to a low (2.5 percent) tax. This attempt died on the House floor.

By the summer of 1907, a few prominent proponents of asset currency, having become discouraged by the movement’s lack of political success, began to desert it and to instead join those who were prepared to limit the privilege of issuing notes not backed by bonds either to a central bank or to a handful of regional banks or bank associations.57 One of the defectors was Frank Vanderlip, who was to play a prominent behind-the-scenes part in the National Monetary Commission.

Vanderlip had been the assistant of Lyman Gage, McKinley’s Secretary of the Treasury who, like his chief, “attributed the inept U.S. currency system to serious legal constraints.”58 But his views changed after he was employed by National City Bank, which he quickly turned into “the nation’s largest holder of interior bank deposits.”59 In his 1906 Chamber of Commerce Committee report Vanderlip, instead of insisting as he once had on the need for asset currency and financial deregulation, instead proposed a central bank of issue, authorized to deal, but not to compete, with other banks, controlled by a board consisting partly of presidential appointees.

Despite desertions from its supporters’ ranks and powerful opponents in Congress, until the Panic of 1907 asset currency remained a relatively popular reform alternative. It continued to command the almost universal support of leading monetary economists. And although it faced stiff resistance, resistance to the alternative of a central bank was even stiffer. Warburg’s partner, Jacob Schiff, who himself favored the idea, summed the matter up well in addressing the New York Chamber of Commerce in anticipation of the release of its 1906 report:

The American people at the time of Andrew Jackson, and more so today, do not want to centralize power. They do not want to increase the power of Government. They know that every increase in the power of government, beyond the legitimate functions of government, means the suppression of private energy, and they also know that a central bank would, more or less, just as the SubTreasuries are today, be a government institution… . They do not want to have this mass of deposits, these large deposits, which the government would have to keep in this bank, controlled by a few people. They are afraid of the political power it would give and the consequences. That is the feeling of the people of this country.60

According to Wicker, even as late as the first half of 1908 “no one … thought a central bank would be at the top of the banking system reform agenda.”61 Although it is too strong to say, as Wicker does, that asset currency plans still “monopolized the banking reform debate,” such plans remained prominent.62 While the central bank plan “appealed to a handful of journalists and professors,” it had no friends in Congress, where preferences were divided between those who favored an asset currency reform and others, including Aldrich, who still remained “enamored of the system of National Bank Notes secured by government bonds.”63

The currency reform movement had thus reached an impasse that only Aldrich himself could break. By electing to convene and direct a National Monetary Commission, Aldrich did at last break it. But he did so in a manner that was to decisively sway the balance of the movement in favor of a central bank.

The Aldrich-Vreeland Act

Although an interval of economic expansion between August 1904 and May 1907 reduced the pressure for monetary reform, the Panic of 1907 led to calls for immediate legislation.64 “Reform,” Lowenstein writes, “was suddenly the rage. Proposals poured into Congress.65

The more authoritative proposals once again called for asset currency, including yet another Fowler bill essentially repeating his 1906 attempt. But because of the Aldrich-led Senate Finance Committee’s “stern opposition … against any form of ‘asset-currency,’”66 the measure that ultimately won approval—the Aldrich-Vreeland Act of May 30, 1908—amounted, not to a permanent and coherent plan for currency reform, based on asset currency or otherwise, but, in the words of Indianapolis Plan author J. Laurence Laughlin, to “a curious compound of conflicting views, compromise, haste, and politics.”67

The “compromise” to which Laughlin refers began as one between Fowler’s asset currency bill and another reply by Aldrich. Aldrich’s plan, renewing his 1903 call for allowing national banks to secure their notes with the same sorts of bonds that had secured the notes of antebellum wildcat banks, was for that and other reasons “ridiculed in the House by the representatives of industry and banking.”68 “One can scarcely avoid the conclusion,” Laughlin observed in his own scathing assessment of Aldrich’s plan, that it “represented only the stolid personal prejudices of a very few mistaken politicians, who held the reins of power.”69

Fowler’s proposal was, on the other hand, exceedingly ambitious: unlike some previous asset currency plans, it called for national banks to retire all of their bond-secured notes at once, rather than gradually, while allowing them to issue asset-backed notes up to 100 percent of their capital, rather than up to 40 or 50 percent of that capital. Realizing that neither the Fowler Bill nor the Aldrich alternative could succeed, Rep. Edward Vreeland (R‑NY) offered a compromise measure resembling Aldrich’s but allowing commercial paper as well as bonds to serve as backing for emergency note issues. Fowler, however, refused to report Vreeland’s bill from his committee.70 Fowler’s refusal to compromise cost him the support of a House that “was not ready to throw over all bond security,” as well as that of the American Bankers’ Association, which instead of endorsing his plan, developed its own, less aggressive asset currency proposal.71

The Republican leadership answered Fowler’s intransigence by calling a party caucus to bring Vreeland’s bill before the House. The House, in turn, resolved to discharge the bill from Fowler’s committee, guaranteeing the bill’s passage there. Fowler in the meantime reintroduced a more moderate version of his bill, only to have Vreeland’s committee set it aside unceremoniously in favor of one of Vreeland’s measures. When the Senate rejected the Vreeland Bill, the matter was referred to a conference committee, which came up with the Aldrich-Vreeland compromise by incorporating large chunks of the Aldrich Bill into the House proposal.

The Aldrich-Vreeland Act was passed on May 30, 1908. Although “there was little enthusiasm for the bill among bankers, and none among the public,” the measure was approved owing to the keen sense of urgency engendered by the recent panic and the fact that the actual reforms it provided for, instead of being permanent, were originally scheduled to expire on June 30, 1914.72 (The Federal Reserve Act would later extend them for an extra year.) Those reforms “authorized banks to form local currency associations and, with the approval of the Treasury secretary, to issue additional National Bank Notes in an emergency.”73 The emergency notes were to be backed first by government securities and second by commercial paper.

The temporary emergency currency provisions of the Aldrich-Vreeland Act were as close as the United States would ever come to establishing a decentralized asset currency. Although the Act did not allow national banks to directly issue asset-backed notes, it at least allowed some of them to do so indirectly, albeit subject to a stiff tax, by organizing themselves into currency associations.74

Although it didn’t last long, the Aldrich-Vreeland asset currency experiment was to prove both beneficial and enlightening. When World War I broke out some months before the Federal Reserve Banks opened for business, the ensuing panic confronted the U.S. monetary system with its “biggest gold outflow in a generation.”75 Put to its only test, the Aldrich-Vreeland emergency currency passed with flying colors.76

Of far greater bearing upon the ultimate course of monetary reform than the Aldrich-Vreeland Act’s emergency currency provisions was the Act’s single paragraph establishing a National Monetary Commission, the mission of which was “to inquire into and report to Congress, at the earliest date practicable, what changes are necessary or desirable in the monetary system of the United States or in the laws relating to banking and currency.” According to Vreeland’s April 20, 1908, testimony before the House Committee on Banking and Currency, although Aldrich promised that the Senate would draft a bill providing for such a commission, no such legislation was introduced there.77 “The main thing,” Vreeland continued, “is that we shall have a commission… which shall study the need of such revisions in our banking laws as may be necessary, and who shall take time to do it intelligently, and report at a future session of Congress upon the whole matter.” Vreeland therefore allowed his own bill to be amended to provide for the proposed Monetary Commission.78 In short, had the matter been left to Aldrich’s own committee, the commission that would determine the future course of U.S. monetary reform, over which Aldrich was to preside like Suleiman, might never have been launched.

The Commission

Officially the National Monetary Commission had 18 members, including Aldrich and Vreeland, who served as its chair and vice chair, respectively. The rest consisted of 8 senators appointed by Vice President Charles Fairbanks and 8 representatives chosen by the Speaker of the House Joseph Cannon. Of the senators, 4 were Republicans and 3 were Democrats, while of the representatives 5 were Republicans and 3 were Democrats. Arthur Shelton served as the Commission’s secretary; A. Piatt Andrew served as its special assistant.

To accomplish its task the Commission was expected “to examine witnesses and to make such investigations and examinations, in this or other countries, of the subjects committed to their charge as they shall deem necessary.”79 These interviews, examinations, and investigations were supposed, in Andrew’s words, to serve as the “foundation” for the Commission’s report to Congress, which was to include its proposed legislation.

The Commission’s first gathering took place at Rhode Island’s Narragansett Pier in July 1908. There the Commission “voted to send representatives … to the leading countries of Europe to collect information with regard to the organization of banking in these countries.”80 The European tour began on August 12 and ended on October 13, 1908, although most commission members returned in late August, leaving Aldrich and Andrew to complete the mission.

The investigations of both foreign and domestic monetary arrangements undertaken or otherwise sponsored by the Commission were complemented by an equally impressive U.S. “education” campaign. “Reform,” wrote Wall Street Journal editorial assistant Sereno S. Pratt to Aldrich in February 1908, “can only be brought about by educating the people up to it.”81 In fact, Aldrich had understood all along that “the public had to be educated before he could propose legislation.” Consequently, as soon as the Commission had formulated its proposals, he and his associates proceeded “to blanket the country with educational literature.”82 The Wall Street Journal itself took part in this campaign, by publishing a 14-part series of opinion pieces authored by Charles Conant, a journalist and member of the New York Chamber of Commerce Commission on Currency Reform, which had earlier reported in favor of establishing a U.S. central bank.

The first fruits of the Commission’s efforts, consisting of 23 volumes of studies commissioned and interviews undertaken by it, began to appear in the autumn of 1910. Although they were completed around the same time, the Commission’s report and actual reform plan were not made public until January 17, 1911. The midterm election had, in the meantime, handed control of the House to the Democrats. Consequently Aldrich, who had originally intended to present his plan to Congress immediately following its completion, chose to withhold it for another year with the aim of gaining broader support for it, including the ABA’s much-coveted endorsement. With that strategy in mind the draft bill was sent to leading bankers and economists, who were asked to suggest revisions. According to Andrew, “as many as twenty modified drafts were printed during the course of that year as a result of continuous consultation with hundreds of important people.”83 Having at last gained the ABA’s approval, Aldrich introduced his bill to the Senate in January 1912. That step having at last been taken, the business of the National Monetary Commission was formally over.

The centerpiece of the Aldrich plan was a National Reserve Association, located in Washington and operated as a cooperative of subscribing state and national banks, with 15 branches assigned to districts throughout the country. The districts would, in turn, be divided into portions assigned to local associations, each made up of at least 10 banks. The local associations of each district would select both their own boards and, collectively, that of the Reserve Association’s district branch. Subscribing banks would also directly or indirectly select 40 of the National Reserve Association’s 46 directors. The rest would consist of government appointees, including the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of Commerce and Labor, the Secretary of Agriculture, and the Comptroller of the Currency.

The National Reserve Association would have the power, through its branches, of issuing notes against its members’ prime commercial paper, and so would serve as an indirect means by which those members could place currency into circulation that was not backed by government bonds. But although it provided in this way for a kind of asset currency, Aldrich’s proposal was a far cry from genuine asset currency plans such as those devised at Baltimore and Indianapolis, or those offered later by Congressman Fowler. While “asset currency” in its original sense meant currency backed by ordinary bank assets, rather than by government bonds, the Aldrich plan allowed banks to acquire currency only in exchange for short-run commercial paper. Regardless of the soundness of their other assets, banks that lacked such paper would have no more access to currency than they would have had without the reform.

Instead of having them apply for currency to a semi-centralized agency, on terms established by that agency, genuine asset currency plans also allowed national banks themselves, if not all banks, to issue their own asset-backed notes. The idea was to let national banks stand on their own feet, instead of having them lean on other institutions, whether private or public. Far from seeking the same end, the Aldrich plan went in precisely the opposite direction, by calling for the eventual substitution of National Reserve Association notes for those of national banks themselves. In other words, the plan called for removing banks altogether from the currency business, and turning that business over to a semi-public monopoly.

A Trojan Horse for Wall Street

Although it pretended to be an objective and bipartisan body of 18 senators and representatives, all working together to determine the best means for ridding the U.S. economy of financial crises, in truth the National Monetary Commission served from the very beginning as a sort of Trojan horse, the purpose of which was to convey Aldrich’s—which is to say Wall Street’s—preferred scheme for currency and banking reform through Congress.

According to no less an authority than A. Piatt Andrew, the Commission’s “special assistant” who was responsible for composing its report and editing its other publications, the Monetary Commission “was a one-man show.”84 Aldrich, Andrew says, “expected little help from the members of the commission, most of whom had little to offer in the way of scholarship and experience in financial matters and all of whom he knew he could control… . So far as the Commission itself was concerned, the Senator’s principal idea was to keep its members happy until he had a bill ready and then get their approval.” Aldrich held bimonthly meetings with commission members in New York so as to assure them that “they were not being left out of the picture.” But those meetings were otherwise of no real significance. “Occasionally some member would have an idea to which the Senator would listen patiently, but following some general discussion one of his friends on the Commission would usually move that ‘the matter be left to the Chairman with the power to act,’” and that would be the end of that.85

If one man’s dominance of a commission of inquiry wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, it certainly was so in this instance, for Aldrich was notorious for being “fiercely partisan.”86 “[T]he old leopard,” said Andrew Gray of Aldrich, “could not change his spots, and his identification with the crusade did not enhance its political prospects.” Despite Piatt Andrew’s having “made every effort to enlist bipartisan support,” the Commission’s proposal “was universally dubbed the ‘Aldrich Plan.’”87 The fortunes of that plan thus remained inextricably intertwined with those of the Republican Party itself.

Handicapped as it was by Aldrich’s partisanship, the Commission was rendered still more so by its chairman’s notoriously cozy relationship with Wall Street. “In the marriage of business and government,” Lowenstein observes, “Aldrich felt no discomfort.”88 His close ties to Wall Street were especially conspicuous. In “The Treason of the Senate,” his muckraking Cosmopolitan series, David Graham Phillips described Aldrich as “the intimate of Wall Street’s great robber barons” and “the chief agent of the predatory band which was rapidly forming to take care of the prosperity of the American people.”89

The popular perception of Aldrich—or at least that of Democrats and many western Republicans—was no different. It is well-captured by a 1905 cartoon depicting him as the crowned king of the Senate, a tiny Teddy Roosevelt prostrate before him. Other Republican senators around him are busy welcoming “The Trusts” into the Senate Chamber, reading a ticker tape, or otherwise enjoying the fruits of crony capitalism. At the cartoon’s upper right corner the senator’s office door appears, with “VESTED INTERESTS” painted below his name on its etched-glass window.

Aldrich’s close ties to Wall Street were evident in his choice of advisers. Although he treated his fellow commissioners as mere ciphers, he did not hesitate to take the advice of powerful financiers to heart, particularly ones closely associated with Morgan and Rockefeller. It is now common knowledge that the Aldrich Plan, despite having been presented as the fruits of the Commission’s labor, was entirely the work of Aldrich and his small circle of advisers—Henry P. Davison, Frank Vanderlip, Paul Warburg, Piatt Andrew, and (according to Vanderlip) Benjamin Strong—who cobbled it together during their November 1910 “duck hunt” at Jekyll Island.90

The Jekyll Island meeting is now notorious, but it remained a well-kept secret until Aldrich’s biographer, Nathaniel Stephenson, spilled the beans in 1930. No word of it had ever been breathed to the other Commission members. The need for secrecy was perfectly obvious. By 1910 a lack of “Wall Street Influence” had become, in Lowenstein’s words, “the litmus test of monetary reform,” and one that President William Taft himself had promised the National Monetary Commission would pass.91 Yet the Jekyll Island gathering had Wall Street written all over it. The island itself was a Morgan retreat, while the participants, apart from Andrew, were all Wall Street luminaries. Davison, who arranged the retreat, besides being a senior Morgan partner, was vice president of the First National Bank of New York, a founder of Banker’s Trust, and a director of four other major New York City banks or trusts.92 Vanderlip was then president of the Morgan-controlled National City Bank, and would soon help the Morgan interests to gain control of the National Bank of Commerce. Warburg had been a partner in Kuhn, Loeb & Co. since 1902. Strong, finally, was vice-president of Bankers Trust.93

Gaudy conspiracy theories have portrayed the Jekyll Island gathering as a plot aimed, as Lowenstein puts it, at “confiscating the people’s wealth.” But to portray the participants as “patriotic conspirators” who merely wished “to achieve a worthy public reform,” as Lowenstein himself does, is no less misleading.94 The truth, as McCulley observes, is that the Jekyll Island bankers were concerned, above all, about “the viability of the banks that they represented,” and particularly about how those banks’ “interior correspondents continued to subject them to sudden calls for cash” that often “placed an almost unbearable strain on the financial center.”95 Vanderlip in particular had reason to be concerned:

While National City Bank officials increasingly bound their assets to a declining securities market, the bank’s interior balances doubled between 1900 and 1910… . Heightened financial instability at New York rendered problematic Vanderlip’s numerous projects for expanding the National City Bank’s activities both domestically and internationally and severely impaired his bank’s ability to smoothly channel financial resources to its corporate clients.96

Aldrich’s advisers wanted stability; but they only wanted as much of it as they could have while preserving the pyramiding of bank reserves in New York. They therefore rejected reforms that would have made other banks less dependent upon them, by granting those banks direct access to the New York money market and enhancing their freedom to issue banknotes. Although the dismissal of such popular and sensible alternatives would have been surprising had the Aldrich team merely “wanted a more resilient banking system,” allowing for those authors’ vested interests, it wasn’t surprising at all.97 Nor was it surprising that, instead of referring to the adverse effects of unit banking and other structural sources of U.S. financial instability, as asset currency proposals had done, the National Monetary Commission’s official report ignored them.98

Instead of allowing banks to branch, so that they might maintain control of their own reserves while still employing those reserves efficiently, the Aldrich Plan asked them to maintain deposits at 15 district “reserve associations,” each of which acted as a branch of a National Reserve Association in Washington. The plan also prohibited reserve associations from paying interest on reserves, while making no change in the National Banking Act’s provisions allowing banks to count correspondent balances in reserve city and central reserve city banks as part of their legal reserves. These arrangements were designed to assure city correspondent banks, and the big New York banks especially, that the new reserve associations would not compete with them for bankers’ deposits.99 As Alfred Crozier observes in U.S. Money vs. Corporation Currency—an excoriating, 400-page assessment of the Aldrich plan,

The chief curse and evil of the present banking system is the law that years ago was instigated by Wall Street, under which a large portion of the entire cash of the country held by the banks, nearly one-third of it, by means of the reserve system is concentrated in a few big Wall Street banks… . And this Aldrich bill practically makes no change in this reserve system. The banks of the entire country can go on depositing their “cash reserve” in Wall Street, and will do so, because Wall Street banks pay interest on such deposits and the National Reserve Association is prohibited from doing so.100

Piatt Andrew, who composed the Commission’s report, had no qualms about catering to Wall Street’s needs. Almost uniquely among economists at the time, he was himself a champion of unit banking who, instead of seeing it as a source of weakness and instability, waxed poetic over its supposedly egalitarian tendencies. “Nowhere else,” he observed on the eve of the 1907 panic, “will one find such equality of importance among the banks… or such mutual independence of action.”101 That the New York banks, whose agenda he helped to carry out, were more equal than all the others, doesn’t appear to have weakened Andrew’s determination to preserve the correspondent system status quo.

To allow Wall Street to steer the Commission to an outcome it considered favorable was one thing; to publicly justify the course taken was another. Aldrich tried to accomplish the last goal by claiming that branch banking was insufficiently popular to have merited the Commission’s attention:

Of course, I realize that there are in this country a great many intelligent men who think we ought to have a system of branch banking like the Canadian [sic]; but unless I greatly mistake the character of the American people that will not be possible. In my judgement any system which is to be adopted in this country must recognize the rights and independence of the 25,000 separate banks in the United States… .

The men who deposit in or borrow from small country banks, or banks in the large towns, who have been accustomed to dealing with men who are their neighbors and friends who have a sympathetic appreciation of their wants, will not be willing to consent that legislation shall authorize the displacing of such banks by agents sent from the banks of New York or Chicago to conduct business in these smaller communities.102

The palpable weakness of Aldrich’s argument betrays its insincerity. If clients of “small” banks really did prefer them to potential interlopers from New York or Chicago, that was a reason for other banks to refrain from entering the smaller banks’ markets, rather than one for legally prohibiting such entry. In truth Aldrich cared, not about the well-being of small banks’ country clients, but about that of New York bankers who stood to lose their correspondent business if branch banking was permitted.

The Commission’s out-of-hand rejection of branch banking was but one component of its general rejection of the asset currency approach to monetary reform in favor of a central bank–based alternative. Instead of drawing attention to the part bond-deposit requirements had played in making the currency supply inelastic, as all previous discussions of the topic had done, the Commission made hardly any mention of it; and far from recommending that those requirements be repealed or at least relaxed, its plan looked forward to the complete replacement of commercially supplied banknotes with those issued by the National Reserve Association.

Aldrich understood perfectly well, of course, that a call for any sort of central bank would face resistance as stiff, if not stiffer, than one for unlimited branch banking. He also understood that his planned National Reserve Association was but a thinly disguised central bank, and that it would be widely recognized as such. Addressing the Economic Club of New York in November 1909, he admitted that the commission’s plan was likely to meet with the objection “that no organization which we may suggest can be adopted on account of political prejudices of the past or of the present.”103 But this time, rather than regarding public resistance as fatal, he expected to prevail against it:

I have the utmost confidence in the intelligence and ultimate good judgement of the American people, and I believe if it should be thought wise by the commission, supported by the consensus of intelligent opinion of the people of the United States, to adopt any system, that neither the political prejudice of the past nor the ghost of Andrew Jackson … will stand in the way.104

In the event, the ghost of Andrew Jackson was indeed laid to rest. But if the Commission was able to manage that, surely it might also have managed to overcome objections to branch banking, and therefore to asset currency, had it only been willing to pursue this alternative agenda.

In truth the Aldrich plan, rather than reflecting the state of public opinion, reflected Aldrich’s personal preferences, as informed by his intimate circle of advisers. Of those preferences the most significant consisted of Aldrich’s “conclusion that a central bank was the solution to the United States banking problem,” which, according to McCulley, he appears to have arrived at “with unseemly haste” after a long career as Congress’s “leading defender of the financial status quo.”105 Here again, Aldrich’s preferences aligned with Wall Street’s, for the Wall Street bankers, and Vanderlip in particular, had come to see a central bank as the best means for preserving their correspondent business whilst protecting them from the shocks to which that business exposed them.

The first evidence of Aldrich’s own conversion to central banking occurs in the Monetary Commission’s fall 1908 European itinerary, which concentrated on the central bank–based arrangements of England, Germany, and France.106 A similar bias is evident in the Commission’s publications, nine, five, and three volumes of which are, respectively, devoted to studies of the German, French, and English banking systems. When these studies were being commissioned, only 21 countries—a third of the world total—had central banks. Yet of the remaining countries Canada alone is represented, in volumes (both excellent) by Joseph French Johnson and R. M. Breckenridge.107 In short, rather than supplying an objective foundation for the Commission’s conclusions, the Commission’s studies instead constituted, in Livingston’s words, “a formidable brief on behalf of a central bank.”108

Nor was there any compelling a priori reason for the central bank–oriented nature of the Commission’s investigations. Although Aldrich’s claim that the central bank systems that received the lion’s share of the Commission’s attention had witnessed fewer financial panics than the United States, it was also true, as Charles Calomiris and Stephen Haber note in their recent survey of banking crises, that “the U.S. was the only country in the world still suffering from these kinds of panics at the end of the nineteenth century” (my emphasis).109

What is less clear is whether Aldrich intended all along to “prosecute the ideological struggle for central banking,” as Livingston claims,110 or whether he only “became a convert” to the central banking alternative after visiting the Reichsbank, as Wicker maintains.111 There is perhaps some truth to both positions. While the Commission’s European itinerary itself suggests that some central-bank bias was present from the start, according to Warburg, who had long been a lone champion of the central-bank alternative, it was only after the European trip that Aldrich, who had previously shown little interest in Warburg’s plan, not only expressed his approval of it, but chided Warburg for having been “too timid about it.”112

Warburg’s Influence

That Paul Warburg himself played a major role in shaping the Aldrich Plan is beyond doubt. Warburg had favored central banking along German lines ever since his arrival in the United States in 1902, and had been tirelessly campaigning for a U.S. central bank since the beginning of 1907. He first met Aldrich on the day after Christmas, 1907. According to Piatt Andrew, although Aldrich “disliked the tenacity with which Warburg would press his points,” he also realized that Warburg knew more about central banking than other bankers whose advice he sought. Aldrich had been particularly impressed by Warburg’s speech on “A United Reserve Bank for the United States,” which was originally delivered at the New York YMCA on March 23, 1910, with thousands of copies distributed by the New York Merchant’s Association. And although, at Jekyll Island, the too-frequently needled senator often cut Warburg off in mid-sentence, he did so “only to reintroduce later the point Warburg had been making as his own.”113

Warburg had no patience for proposals calling for a decentralized asset currency and related, deregulatory reforms. Rather than ever delving into the root causes of U.S. financial instability, as other reformers had done, he took as his starting point the assumption that the German system, with which he was most familiar, was ideal.114 Noting that that system avoided the “inelasticity” that plagued the U.S. arrangement, he, like many commentators since, concluded that the U.S. currency system was inelastic because it lacked a central bank—a diagnosis that allowed for only one cure. In a January, 1908 address at Columbia University, for example, Warburg dismissed as “bad” any reform measure “which accentuates decentralization of note issue and of reserves” or “which gives to commercial banks power to issue additional notes against their general assets without restricting them in turn in the scope of their general business, and without creating some additional independent control, endorsement, or guarantee.”115

A comparison of Warburg’s opinion—that the best way to have plenty of cash available for an emergency was to keep it all in a “central reservoir”—with Walter Bagehot’s very different perspective, as set forth in Lombard Street, is highly instructive. England had long had what Bagehot termed a “one reserve” banking system. “All London banks,” he observed, “keep their principal reserve on deposit in the Banking Department of the Bank of England. This is by far the easiest and safest place for them to use. The Bank of England thus has the responsibility of taking care of it.”116 But far from viewing this concentration of reserves as a blessing, Bagehot saw in it the ultimate cause of British financial instability. “I shall have failed in my purpose,” he wrote,

if I have not proved that the system of entrusting all our reserve to a single board, like that of the Bank directors, is very anomalous; that it is very dangerous; that its bad consequences, though much felt, have not been fully seen; that they have been obscured by traditional arguments and hidden in the dust of ancient controversies.117

A far safer alternative, in Bagehot’s opinion, was the “natural” one “of many banks of equal or not altogether unequal size,” each keeping its own reserves, “which would have sprung up if Government had let banking alone.”118 It was only because he believed that “[n]othing could persuade the English people to abolish the Bank of England” that Bagehot, instead of proposing that England “return to a natural or many-reserve system of banking,”119 instead offered the now-famous advice that there ought to be a clear understanding between the Bank and the public that, since the Bank holds our ultimate banking reserve, they will recognize and act on the obligations which this implies; that they will replenish it in times of foreign demand as fully, and lend in times of internal panic as freely and readily, as plain principles of banking require.120

As if to settle any doubt as to his first-best ideal, Bagehot ended Lombard Street with a final apology for having proposed something else:

I know it will be said that in this work I have pointed out a deep malady, and only suggested a superficial remedy. I have tediously insisted that the natural system of banking is that of many banks keeping their own cash reserves, with the penalty of failure before them if they neglect it. I have shown that our system is that of a single bank keeping the whole reserve under no effectual penalty of failure. And yet I propose to retain that system, and only to mend and palliate it.

I can only reply that I propose to retain this system because I am quite sure it is of no manner of use proposing to alter it.… You might as well, or better, try to alter the English monarchy and substitute a republic, as to alter the present constitution of the English money market, founded on the Bank of England, and substitute for it a system in which each bank shall keep its own reserve. There is no force to be found adequate to so vast a reconstruction, and so vast a destruction, and therefore it is useless proposing them.

No one who has not long considered the subject can have a notion of how much this dependence on the Bank of England is fixed in our national habits.121

Thus Warburg, like many central banking apologists since, took as his scientific ideal an arrangement that Bagehot had considered fundamentally unsound. He did this, moreover, despite the fact that the idea of a central reserve bank, far from having been fixed in American habits, was one Americans had long opposed.

The Fate of the Aldrich Plan

The long interval between the National Monetary Commission’s launch and the completion of its report was due to Aldrich’s involvement in the tariff debate of 1909, and to his consequent preoccupation with attacks upon him by insurgent Republicans that would ultimately lead to his decision to retire from the Senate. The delay meant that the Aldrich Plan could not be completed until after the 1910 election, which gave Democrats a majority in the House for first time in 16 years. The lame-duck senator’s other critics were thus joined by New York bankers, who “publically chastised Aldrich for procrastination that endangered the movement for a central bank.”122

The plan’s hopes now rested on the success of the National Citizens’ League—an organization launched in April 1911, at Warburg’s urging, to “carry on an active campaign of education and propaganda for monetary reform, on the principles... outlined in Senator Aldrich’s plan.”123 The League’s purpose was to win support for the plan from progressives who tended—with good reason—to regard any scheme with which Aldrich was associated as one hatched by Wall Street. Consequently, Warburg arranged to have its Executive Committee consist entirely of Chicago businessmen and politicians, with Laurence Laughlin (who, like Vanderlip, had by then abandoned the cause of a fully decentralized asset currency) serving as its chairman. To gain progressives’ support for the Aldrich plan, the League argued in favor of its essential elements, while studiously avoiding any reference to it by name, both in lectures it sponsored and in Banking Reform, its monthly magazine. The League also took pains to insist that the measures it favored, far from catering to Wall Street, or amounting to a call for a central bank, were the best means for avoiding these outcomes.

The National Citizens League was to do more than any other body to overcome Americans’ longstanding aversion to the idea of a U.S. central bank. Yet despite the League’s efforts, Aldrich’s hopes for the success of his own bill were dashed. The bill found no supporters in the Senate. “Republicans were embarrassed by the Aldrich Plan and Democrats were beholden to oppose it.”124 The plan’s bipartisan trappings fooled no one. Nor did it help that Aldrich chose to submit the plan in his own name. “Certainly,” Warburg later wrote, “it was not to be expected that [Democratic representatives] would endorse a bill which carried the name of the outstanding Republican leader.”125 On the contrary: they considered Aldrich anathema.126 Within Aldrich’s own party, on the other hand, Aldrich’s plan was opposed by progressives, and especially by Wisconsin Senator Robert La Follette, who detected excessive Wall Street influence. As the November election approached, even Taft himself gave the plan the cold shoulder.

Nor did the Jekyll Island gathering’s cloak of secrecy prevent others from concluding that Aldrich’s plan was, in fact, a Wall Street concoction. A month before it was finally submitted to Congress, Charles Lindbergh Sr. assailed the plan as a scheme to preserve, and even enhance, the “Money Trust’s” share of the nation’s bank reserves, by requiring state as well as national banks subscribing to the proposed National Reserve Association to conform to the National Bank Act’s reserve requirements.127