Not all Bangladeshi men think that way. In fact, the earning power of women is eroding the custom of bridal dowries. It has also brought about greater responsiveness by the court system toward women. Since women have started working, the “law is on their side,” one woman explained.145

Attitudes toward women are changing, and Kabeer found that earning increased the weight a woman’s priorities carried within the household. “When she brings [in] money, I have to buy her whatever she wants,” explained one factory woman’s husband. He continued, “She may want a new sari or she may say that [our] daughter needs a book …”146

“Because women can work and earn money, they are being given some recognition. Now all the men think that they are worth something,” claimed one woman.147

Tragedies like the Rana Plaza building collapse are horrifying and understandably garner a lot of press. But they should not overshadow the garment industry’s wider-reaching effects on the material well-being and social equality of women in Bangladesh. As one factory worker put it: “The garments have saved so many lives.”148

Conclusion

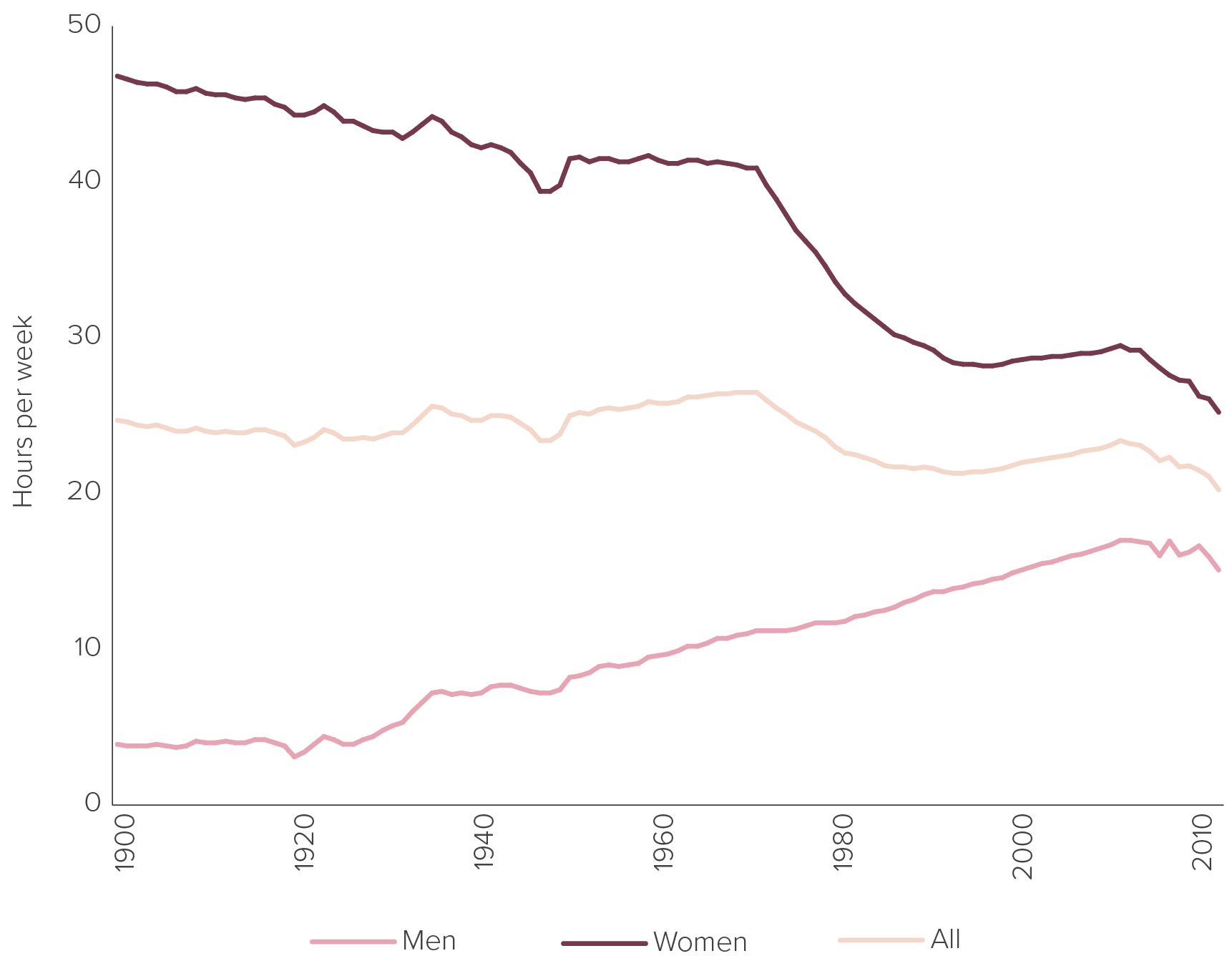

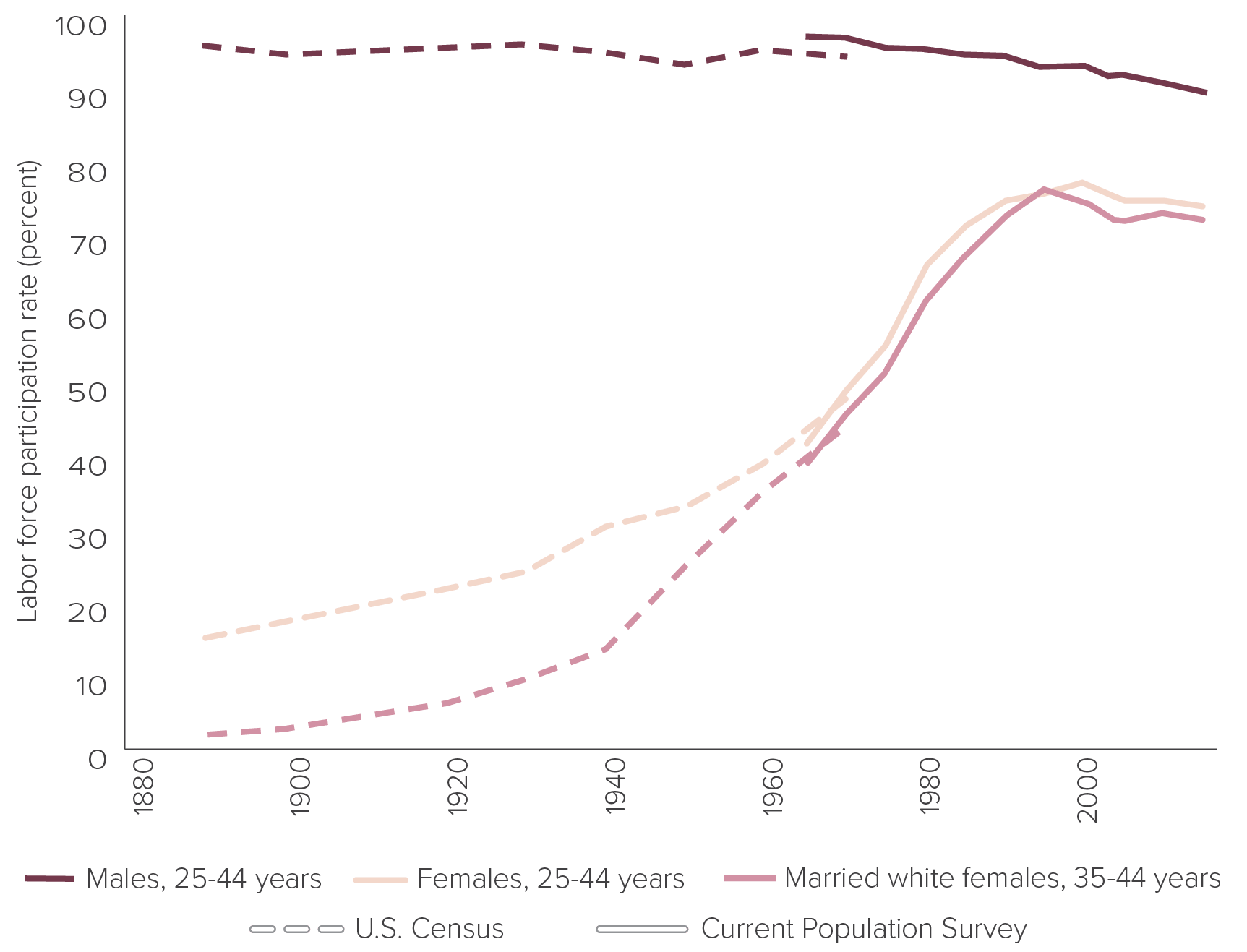

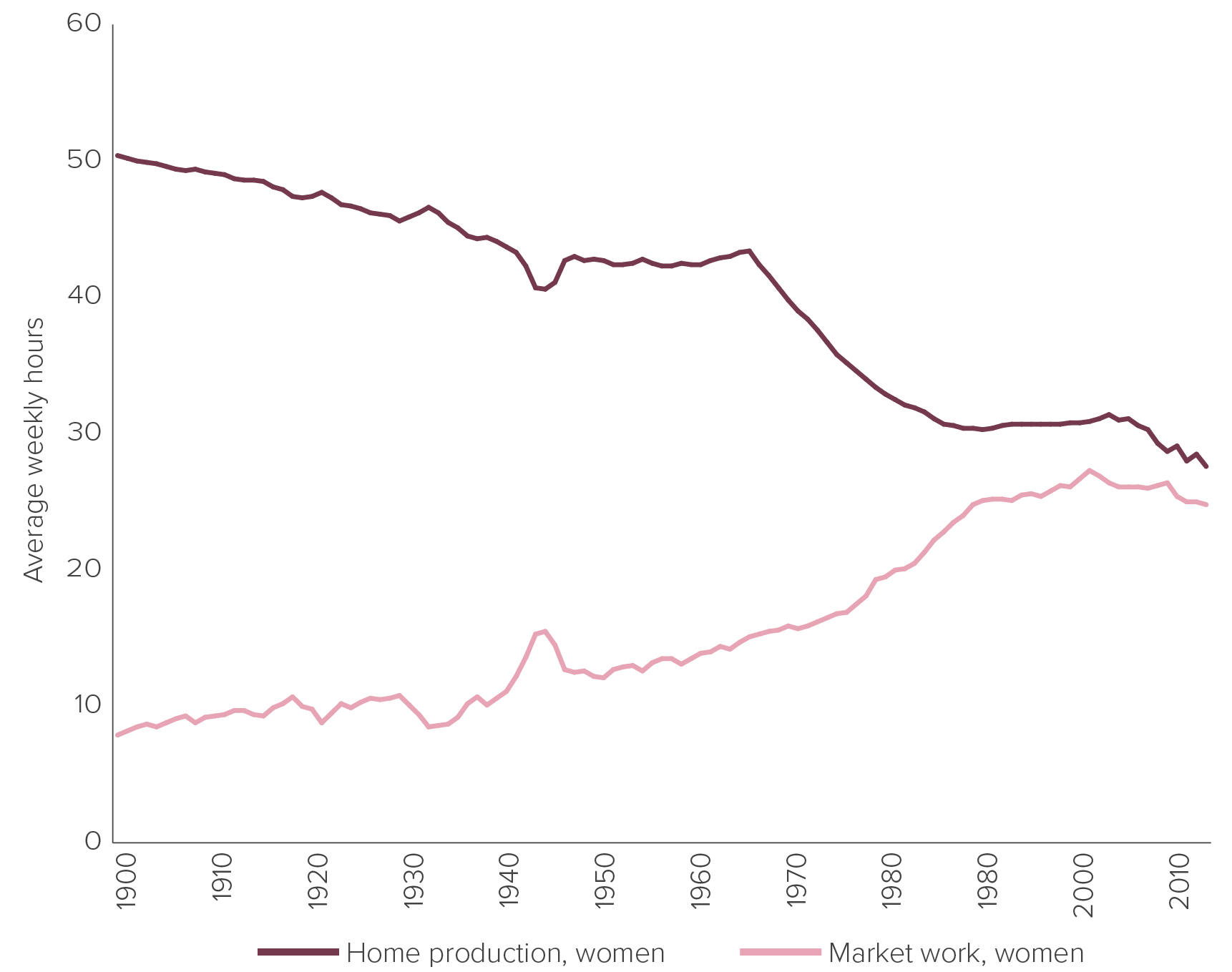

Market-led innovation has improved the lives of women even more so than for men. Women have reaped greater benefits from health advances financed by the prosperity created by free enterprise: female life expectancy has risen faster than men’s and today women outlive men almost everywhere. Women are also less likely to die in childbirth, and falling infant mortality rates have enabled smaller family sizes, giving women more time. Laborsaving household devices have also freed women from the burden of housework. This freeing of women’s time is ongoing as appliances spread throughout the world, and as women spend less time on household production, more of them choose to engage in paid labor.

Labor market participation offers women economic independence and heightened societal bargaining power. Factory work, despite its poor reputation, empowered women in the 19th-century United States by helping them achieve economic independence and social change. Today, the story of the factory girls is repeating itself in new settings across the world, as young women gain economic independence through risk and toil. In China, factory work gave rural women a chance to change their fates and the conditions in their home villages. In Bangladesh it let women renegotiate restrictive cultural norms.

Innovation and market participation enable women to achieve greater material prosperity and promote positive cultural change away from sexism. Progress is still in its earlier stages in many countries, but with the right policies, women everywhere can one day enjoy the same degree of material prosperity and cultural gender equality present in the United States today.

Notes

1 “Human Development Report 2016,” United Nations Development Programme, p. 3, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf.

2 Esther Duflo, “Women Empowerment and Economic Development,” Journal of Economic Literature 50, no. 4 (2012): 1053.

3 Victoria Bateman, “To Understand Britain’s History of Prosperity, Just Look to Its Women,” UnHerd, October 4, 2017; Matthew Willis, “How 17th Century Unmarried Women Helped Shape Capitalism,” JSTOR Daily, December 19, 2017; and Ana Ravenga and Sudhir Shetty, “Empowering Women Is Smart Economics,” Finance & Development 49, no. 1 (2012): 40–3.

4 Max Roser, “Life Expectancy,” Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy.

5 Samuel H. Preston, “The Changing Relation between Mortality and Level of Economic Development,” Population Studies 29, no. 2 (1975): 231–48.

6 Angus Deaton, The Great Escape: Health, Wealth and the Origins of Inequality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), p. 32.

7 Deaton, The Great Escape, pp. 95–7.

8 Deaton, The Great Escape, p. 97.

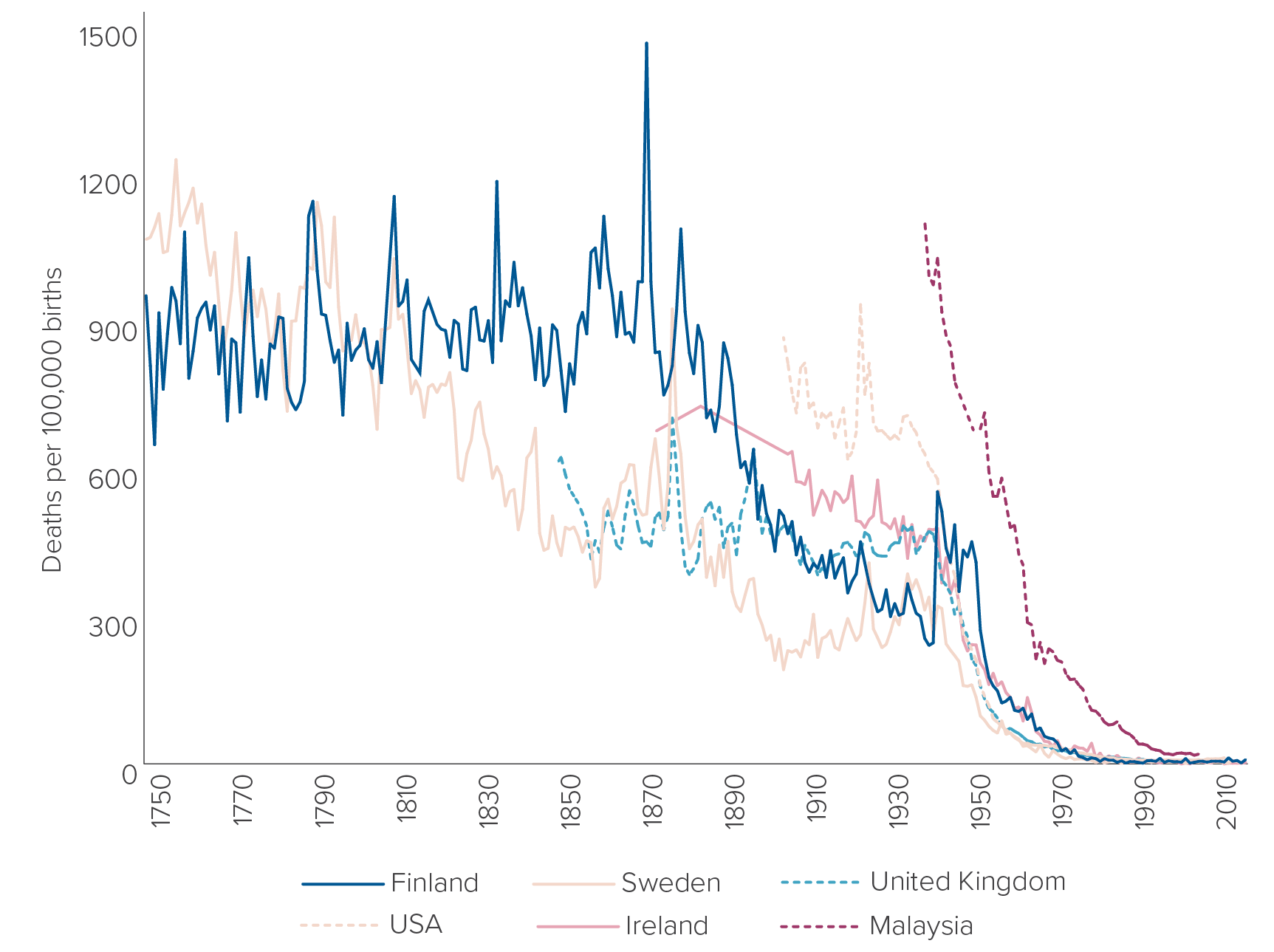

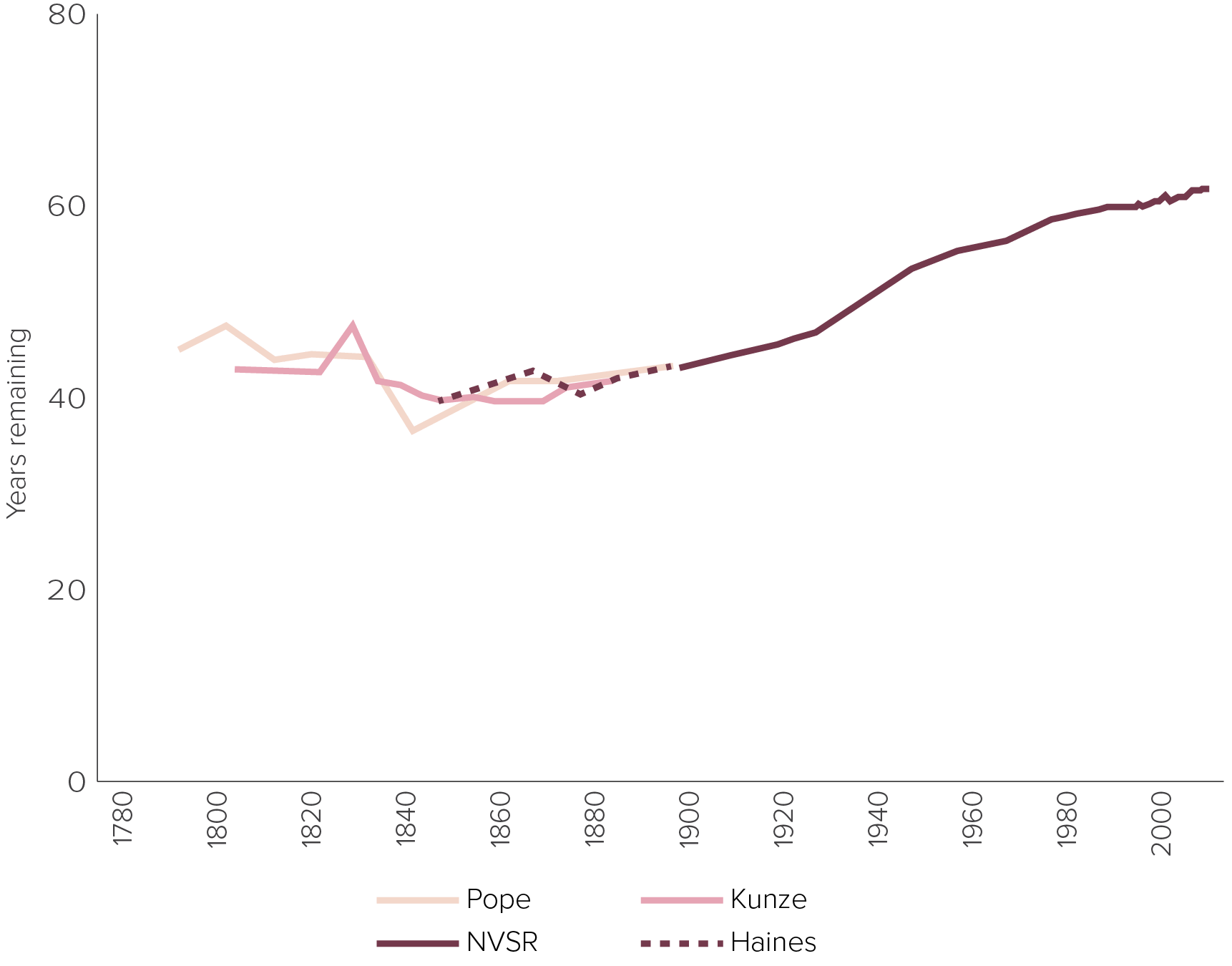

9 Michael R. Haines, “The Urban Mortality Transition in the United States, 1800–1940,” NBER Historical Working Paper no. 134, National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2001.

10 “Middlesex Company Boardinghouse Regulations, Lowell, Massachusetts, c. 1846,” in Thomas Dublin, ed., Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, 2nd ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), p. 11.

11 Ann E. Cudd and Nancy Holmstrom, Capitalism, For and Against: A Feminist Debate (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 39.

12 Deaton, The Great Escape, p. 75; Katherine A. Dettwyer, Cultural Anthropology and Human Experience (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 2011), p. 153.

13 Deaton, The Great Escape, p. 75.

14 Deaton, The Great Escape, p. 75.

15 Deaton, The Great Escape, p. 77.

16 Deaton, The Great Escape, pp. 79–80.

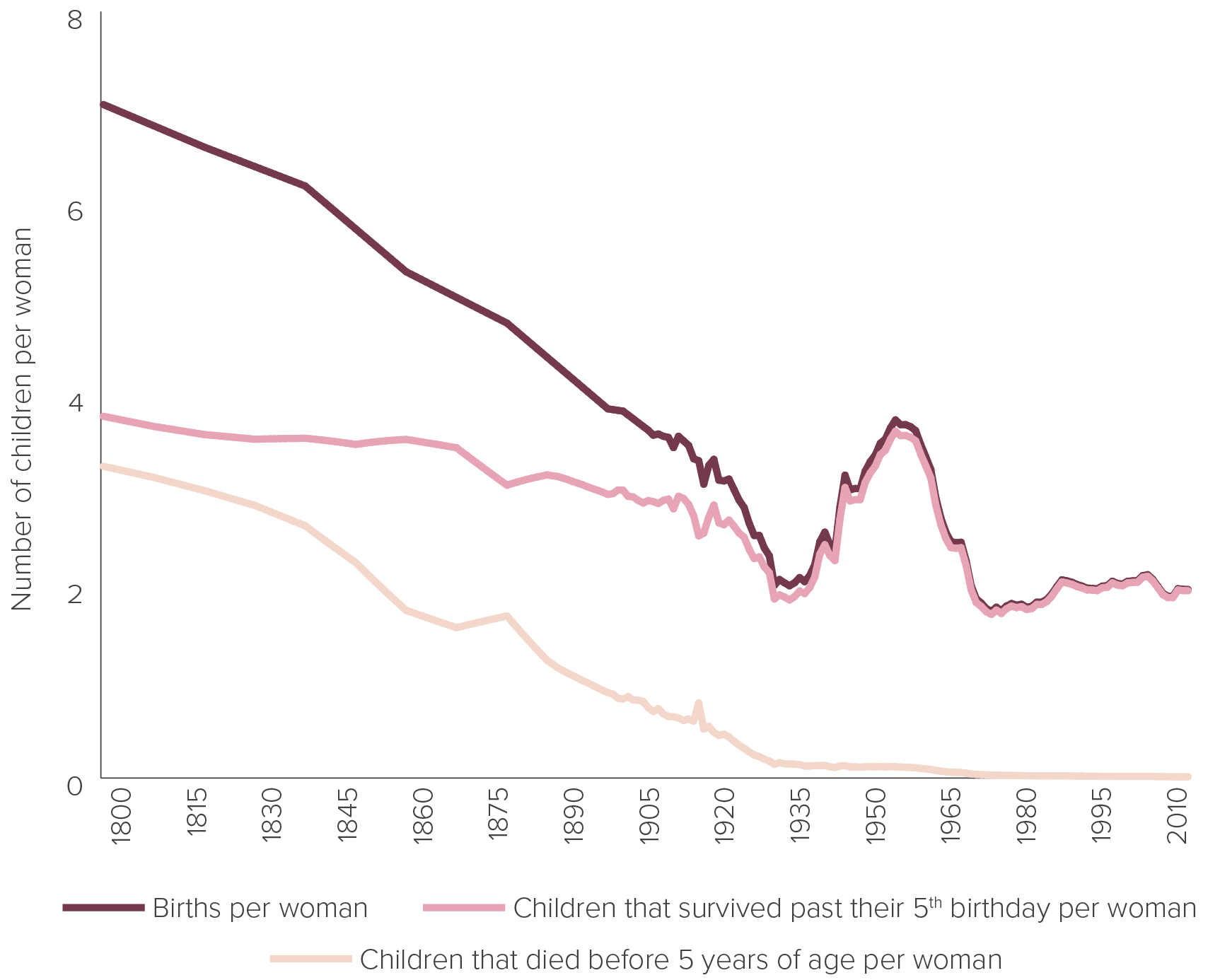

17 Max Roser, “Children that Died Before 5 Years of Age per Woman (based on Gapminder), Children that Survived Past Their 5th Birthday per Woman,” Our World in Data, www.OurWorldInData.org/child-mortality/.

18 Hiram Beltrán-Sáncheza, Caleb E. Finch, and Eileen M. Crimmins, “Twentieth Century Surge of Excess Adult Male Mortality,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, no. 29 (2015): 8993–8.

19 Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: the Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (New York: Viking, 2018), p. 57.

20 Laura Helmuth, “The Disturbing, Shameful History of Childbirth Deaths,” Slate, September 10, 2013, http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science_of_longevity/2013/09/death_in_childbirth_doctors_increased_maternal_mortality_in_the_20th_century.html.

21 Deaton, The Great Escape, p. 66.

22 Noah Smith, “The Population Bomb Has Been Defused,” Bloomberg View, March 16, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018–03-16/decline-in-world-fertility-rates-lowers-risks-of-mass-starvation.

23 “The Desire for Children: Wanted,” The Economist, August 25, 2016.

24 “Demography and Desire: the Empty Crib,” The Economist, August 27, 2016, https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21705678-our-poll-19-countries-reveals-neglected-global-scourge-number-would-be-parents-who.

25 Deaton, The Great Escape, p. 105.

26 Deaton, The Great Escape, p. 101.

27 Marian L. Tupy, “Cost of Living and Wage Stagnation in the United States, 1979–2015,” Cato Institute, January 2016.

28 Deirdre McCloskey, “Post-Modern Free-Market Feminism: Half of a Conversation with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak,” Rethinking Marxism 12, no. 4 (2000): 31, citing Stanley Lebergott, Pursuing Happiness: American Consumers in the Twentieth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), p. 51.

29 Stanley Lebergott, The American Economy: Income, Wealth and Want (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 106.

30 Lindsay P. Smith, Shu Wen Ng, and Barry M. Popkin, “Trends in U.S. Home Food Preparation and Consumption: Analysis of National Nutrition Surveys and Time Use Studies from 1965–1966 to 2007–2008,” Nutrition Journal 12, no. 45 (2013), Table 2.

31 Jesse Rhodes, “Why We Have Sliced Bread,” Smithsonian Magazine, March 7, 2012.

32 Lebergott, The American Economy, p. 105.

33 “Advance Retail Sales: Grocery Stores, Millions of Dollars, Seasonally Adjusted” vs. “Advance Retail Sales: Food Services and Drinking Places, Millions of Dollars, Seasonally Adjusted,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Data, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lIgF.

34 Eileen Bevis, “Home Cooking and Eating Habits: Global Survey Strategic Analysis,” Euromonitor International, April 30, 2012.

35 “Cooking: Consumers’ Attitudes Towards, and Time Spent Cooking,” Global GfK survey, March 2015.

36 Euromonitor, Passport Global Market Information Database, “Economies and Consumers Annual Data,” 2018.

37 Euromonitor, Passport Global Market Information Database, “Economies and Consumers Annual Data,” 2018.

38 Ha-Joon Chang, 23 Things They Don’t Tell You about Capitalism (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010), p. 31.

39 Jeremy Greenwood, Ananth Seshadri, and Mehmet Yorukoglu, “Engines of Liberation,” Review of Economic Studies 72, no. 1 (2005): 109–33.

40 Bill Bryson, At Home: A Short History of Private Life (London: Doubleday, 2010), p. 108.

41 Bryson, At Home: A Short History of Private Life, pp. 107–8.

42 Sarah Skwire, “Capitalism Will Abolish Laundry Day,” Foundation for Economic Education, April 7, 2016, https://fee.org/articles/capitalism-will-abolish-laundry-day/.

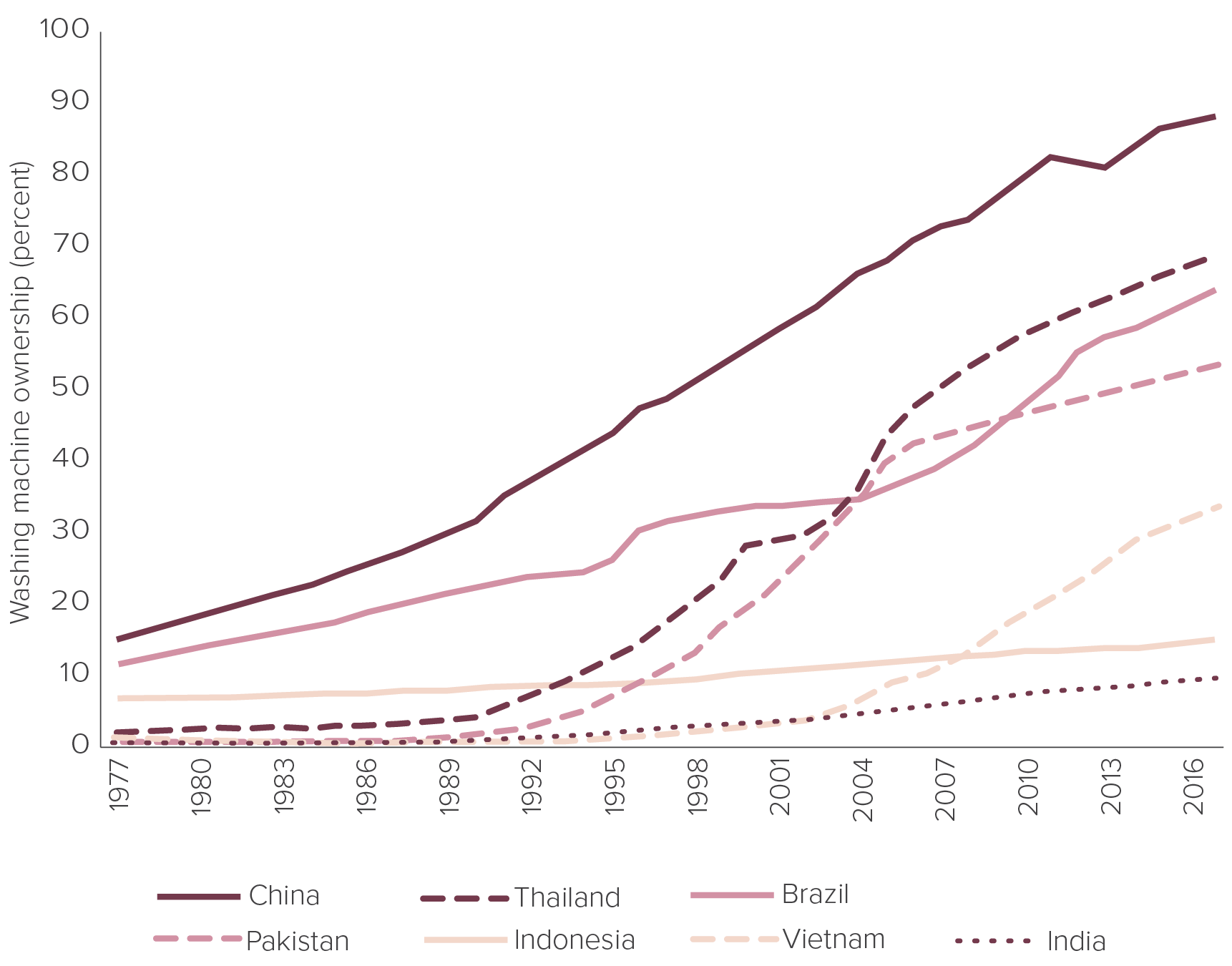

43 Hans Rosling, “The Magic Washing Machine,” TEDWomen 2010 Conference, Washington, D.C., December 7, 2010, https://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_and_the_magic_washing_machine.

44 Slavenka Drakulić, How We Survived Communism and Even Laughed (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), pp. 43–54.

45 Drakulić, How We Survived Communism, p. 43.

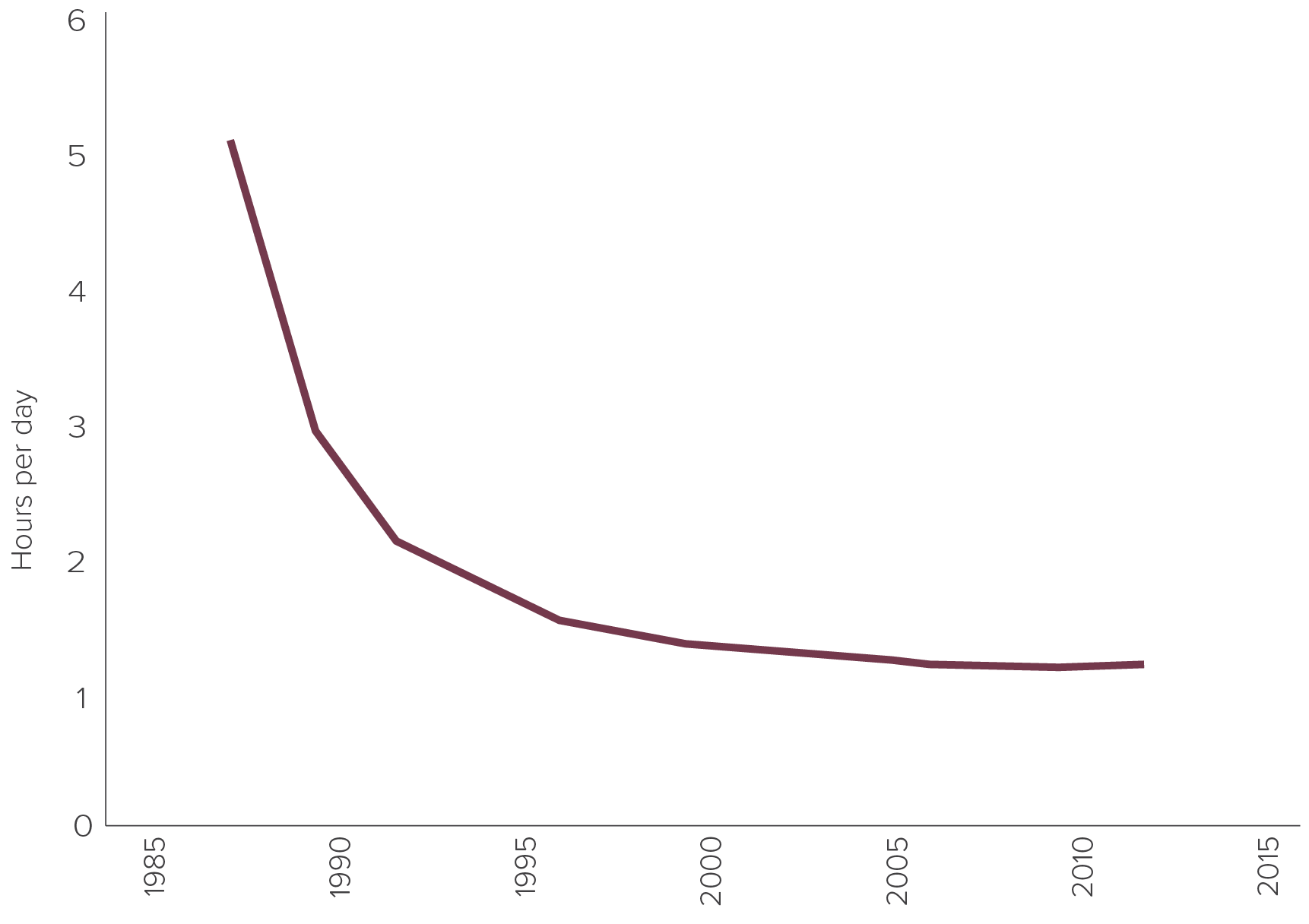

46 “Time Spent on Laundry,” Human Progress, 2016, http://humanprogress.org/static/3264; and Marian L. Tupy, “What Does It Mean to Be Poor Today?” CapX, April 20, 2017, https://capx.co/what-does-it-mean-to-be-poor-today/.

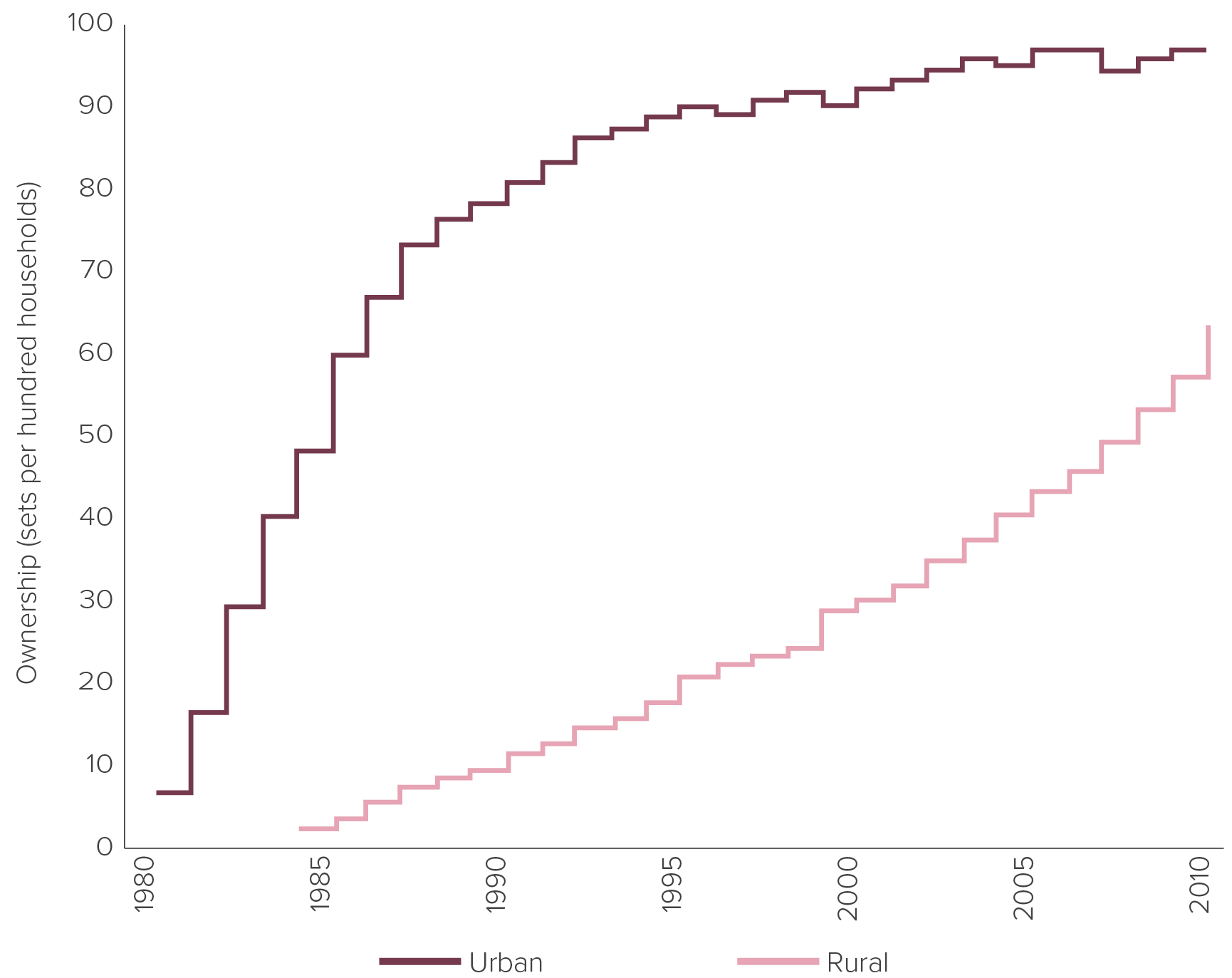

47 Chang, 23 Things They Don’t Tell You about Capitalism, p. 36.

48 Claus Barthel and Thomas Götz, “The Overall Worldwide Saving Potential from Domestic Washing Machines,” bigEE (2013): 1–64; “Global Commercial Washing Machine Market 2016–2020,” Infiniti Research Limited, November 2016; and Nielson, “The Dirt on Cleaning: Home Cleaning/Laundry Attitudes and Trends around the World,” Global Home Care Report, April 2016, p. 25, http://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/nielsenglobal/eu/docs/pdf/Nielsen%20Global%20Home%20Care%20Report.pdf?wgu=12765_54264_15294207023509_6d28c8272e&wgexpiry=1537196702&afflt=ntrt15340001&afflt_uid=w_ftp6T1G58.Es1_5dvWXe2Nf0PPqaIOzgCptiQqJpVc&afflt_uid_2=AFFLT_ID_2.

49 “Number of People Living in Poverty,” Human Progress, 2015, http://humanprogress.org/static/3003.

50 “Total GDP,” Human Progress, 2017, http://humanprogress.org/story/3066.

51 Laili Wang, Xuemei Ding, Rui Huang, and Xiongying Wu, “Choices and Using of Washing Machines in Chinese Households,” International Journal of Consumer Studies 38, no. 1 (January 2014): 104–9.

52 “Household Possession Rate of Washing Machines,” Euromonitor, Global Market Information Database, http://www.euromonitor.com/.

53 Swaminathan S. Anklesaria Aiyar, “Twenty-Five Years of Indian Economic Reform,” Cato Policy Analysis no. 803, October 26, 2016.

54 “Total GDP,” Human Progress, 2017, http://humanprogress.org/story/3066.

55 Pramit Bhattacharya, “In India, Washing Machines Top Computers in Popularity,” Livemint, December 13, 2016, http://www.livemint.com/Specials/bhWpWqj3AFuETVdsC05fdM/In-India-washing-machines-top-computers-in-popularity.html.

56 “2,000,000 Women Walked Away from Washday,” advertisement in LIFE Magazine, April 24, 1950, pp. 117–19.

57 Toshiro Wakayama, Junjiro Shintaku, and Tomofumi Amano, “What Panasonic Learned in China,” Harvard Business Review, December 2012, https://hbr.org/2012/12/what-panasonic-learned-in-china.

58 Marian L. Tupy, “Africa Is Growing Thanks to Capitalism,” CapX, July 22, 2016.

59 Nielson, “The Dirt on Cleaning: Home Cleaning/Laundry Attitudes and Trends around the World.”

60 Valerie A. Ramey, “Time Spent in Home Production in the 20th Century: New Estimates from Old Data,” NBER Working Paper no. 13985, National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2008.

61 Ramey, “Time Spent in Home Production in the 20th Century,” p. 11.

62 Ruth Schwartz Cowan, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York: Basic Books, 1983), p. 100, via Valerie A. Ramey, “Time Spent in Home Production in the 20th Century,” p. 2.

63 Suzanne Lebsock, The Free Women of Petersburg: Status and Culture in a Southern Town, 1784–1860, rev. ed. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1985), p. xv.

64 Quoted in George Frederick Kengott, The Record of a City: A Social Survey of Lowell, Massachusetts (Lowell: Macmillan Company, 1912), p. 15.

65 Harriet J. Farley, “Factory Girls,” The Lowell Offering 2 (December 1840), pp. 17–20, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044021216981;view=1up;seq=32.

66 Alice Kessler-Harris, Out to Work: a History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States, 20th anniversary ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), p. 34.

67 Kessler-Harris, Out to Work, p. 34.

68 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860.

69 “The Fall of the Pemberton Mill,” New York Times, February 16, 1860.

70 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, pp. 169, 180.

71 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, p. 157.

72 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, pp. 181, 192, 169.

73 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, pp. 97–8.

74 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, p. 99.

75 Lucy Larcom, A New England Girlhood (Teddington, UK: Echo Library, 2007).

76 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, pp. 129–30.

77 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, p. 121.

78 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, pp. 135–7.

79 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, pp. 140–1.

80 Dublin, Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830–1860, pp. 142–3.

81 “Free to Booze: The 75th Anniversary of the Repeal of Prohibition,” Cato Policy Forum, December 5, 2008, https://www.cato.org/events/free-booze-75th-anniversary-repeal-prohibition.

82 Robert J. Dinkin, Before Equal Suffrage: Women in Partisan Politics from Colonial Times to 1920 (London: Greenwood Press, 1995), p. 40.

83 Dinkin, Before Equal Suffrage, p. 42.

84 Lebsock, The Free Women of Petersburg, p. 240.

85 Linton Weeks, “American Women Who Were Anti-Suffragettes,” National Public Radio, October 22, 2015.

86 Sylvia Jenkins Cook, “‘Oh Dear! How the Factory Girls Do Rig Up!’: Lowell’s Self-Fashioning Workingwomen,” New England Quarterly 83, no. 2 (June 2010): 219–49.

87 “Eliza Lucas Pinckney, British-American Plantation Manager,” Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Elizabeth-Pinckney.

88 Dylan C. Penningroth, The Claims of Kinfolk: African American Property and Community in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), p. 53.

89 The United States Census of 1860 suggests 12.6 percent of the country’s population was enslaved. See “Recapitulation of the Tables of Population, Nativity, and Occupation,” 1860 Census: Population of the United States, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1864/dec/1860a.html.

90 Lebsock, The Free Women of Petersburg, p. 244.

91 Martha Louise Rayne, What Can a Woman Do: Or, Her Position in the Business and Literary World (Detroit: F. B. Dickerson, 1887).

92 Howard Markel, “Celebrating Rebecca Lee Crumpler, First African-American Woman Physician,” PBS News Hour, March 9, 2016, http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/celebrating-rebecca-lee-crumpler-first-african-american-physician/; and “Charlotte E. Ray: American Lawyer and Teacher,” Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charlotte-E-Ray.

93 Annie Marion MacLean, Wage-Earning Women (New York: MacMillan, 1910), p. 3.

94 Claudia Goldin, “The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women’s Employment, Education, and Family,” Richard T. Ely Lecture, AEA Papers and Proceedings 96, no. 2 (May 2006), https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/goldin/files/the_quiet_revolution_that_transformed_womens_employment_education_and_family.pdf.

95 “Indeed, the idea that paid employment [is] the key to ending women’s subordinate status [has been] subscribed to by a wide spectrum of opinion, from the World Bank to Marxist scholars,” Naila Kabeer, The Power to Choose: Bangladeshi Women and Labour Market Decisions in London and Dhaka (London: Verso, 2000), p. 5.

96 Benjamin Powell, Out of Poverty: Sweatshops in the Global Economy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 120.

97 McCloskey, “Postmodern Market Feminism: Half of a Conversation with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak,” p. 29.

98 Nicholas Kristof, “Where Sweatshops Are a Dream,” New York Times, January 14, 2009.

99 Paul Krugman, “In Praise of Cheap Labor,” Slate, March 1997; Kristof, “Where Sweatshops Are a Dream”; and Jeffrey Sachs, The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time (New York: Penguin Press, 2005), p. 11.

100 Paul Krugman, quoted in Allen R. Myerson, “In Principle, a Case for More Sweatshops,” New York Times, June 22, 1997.

101 Leslie T. Chang, “The Voices of Chinese Workers,” TED Talk, June 2012, https://www.ted.com/talks/leslie_t_chang_the_voices_of_china_s_workers#t‑66532.

102 Chang, “The Voices of Chinese Workers.”

103 This section draws largely on her work.

104 Chang, “The Voices of Chinese Workers.”

105 Leslie T. Chang, Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2009).

106 Chang, Factory Girls, p. 57.

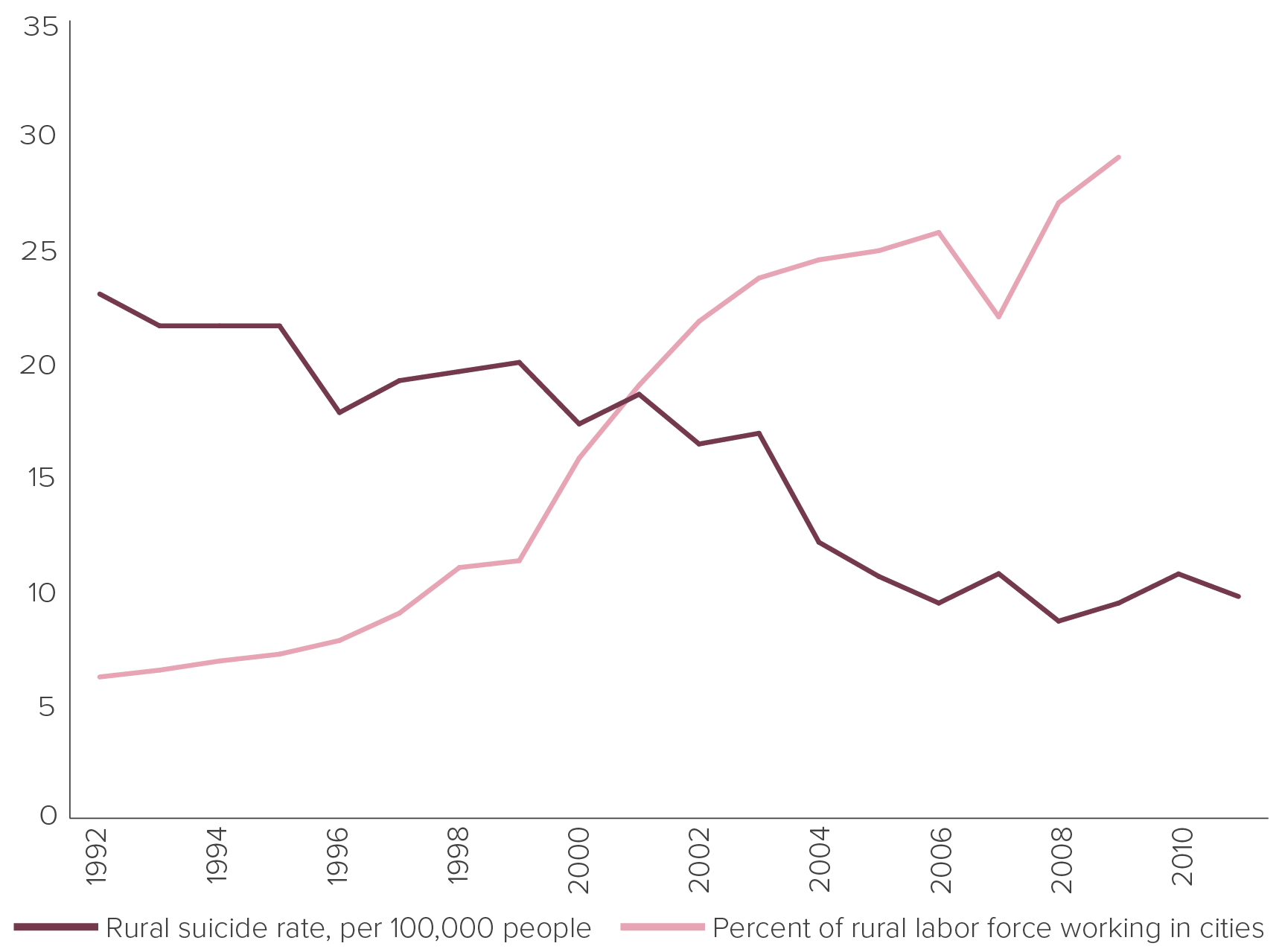

107 “Women and Suicide in Rural China,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/12/09–011209/en/.

108 “Back from the Edge,” The Economist, June 28, 2014; and Feng Sha, Paul S. F. Yip, and Yik Wa Law, “Decomposing Change in China’s Suicide Rate, 1990–2010: Ageing and Urbanisation,” Injury Prevention: Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention 23, no. 1 (2017): 40–45, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27312962.

109 “Women and Suicide in Rural China.”

110 Yuan Ren, “Young Chinese Women Are Committing Suicide at a Terrifying Rate — Here’s Why,” The Telegraph, October 20, 2016, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/life/young-chinese-women-are-committing-suicide-at-a-terrifying-rate/.

111 Jie Zhang, “Marriage and Suicide among Chinese Rural Young Women,” Social Forces 89, no. 1 (September 2010): 319, 321.

112 Zhang, “Marriage and Suicide among Chinese Rural Young Women,” pp. 319, 323.

113 Chang, Factory Girls, p. 105.

114 “Back from the Edge,” The Economist, June 28, 2014.

115 Chang, Factory Girls, p. 27.

116 Chang, Factory Girls, p. 280.

117 Chang, Factory Girls, p. 279.

118 Chang, Factory Girls, p. 404.

119 Zhongdang Ma, “Urban Labour-Force Experience as a Determinant of Rural Occupation Change: Evidence from Recent Urban–Rural Return Migration in China,” Environment and Planning 33, no. 2 (February 2001): 237–55.

120 Leslie T. Chang, “U.S. Misses Full Truth on China Factory Workers,” CNN, October 1, 2012, https://www.cnn.com/2012/09/30/opinion/chang-chinese-factory-workers/index.html.

121 Chang, Factory Girls, p. 224.

122 Chang, Factory Girls, p. 333.

123 Chang, Factory Girls, p. 383.

124 Chang, Factory Girls, p. 383.

125 Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 49. Please note, this section draws largely on her findings.

126 “Globally There Are 746 Million People in Extreme Poverty (in 2013),” Our World in Data, 2013, https://ourworldindata.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Tree-Map-of-Extreme-Poverty-distribution-750x525.png.

127 Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 185.

128 Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 69.

129 Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 69.

130 “In Bangladesh, Empowering and Employing Women in the Garments Sector,” World Bank, February 7, 2017, http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2017/02/07/in-bangladesh-empowering-and-employing-women-in-the-garments-sector.

131 Powell, Out of Poverty: Sweatshops in the Global Economy; and Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 9.

132 Ben Jackson, Threadbare: How the Rich Stitch Up the World’s Rag Trade (London: World Development Movement, 1992), cited in Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 9.

133 Quoted in Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 13.

134 Daniel J. Ikenson, “Cutting the Cord: Textile Trade Policy Needs Tough Love,” Cato Institute Free Trade Bulletin no. 15, January 25, 2005, https://www.cato.org/publications/free-trade-bulletin/cutting-cord-textile-trade-policy-needs-tough-love; and “Harmonized Tariff Schedule (2018 HTSA Revision 11), Section XI: Textile and Textile Articles,” United States International Trade Commission, https://hts.usitc.gov/current.

135 “The Happiest Economic Story in the World Right Now,” Dhaka Tribune, June 4, 2017, http://www.dhakatribune.com/what-the-world-says/2017/06/04/happiest-economic-story-world-right-now/; Rachel Heath and A. Mushfiq Mobarak, “Manufacturing Growth and the Lives of Bangladeshi Women,” NBER Working Paper no. 20383, August 2014; and “Average Age of Women at First Marriage,” Human Progress, http://humanprogress.org/story/2245.

136 “Women Who Were First Married by Age 18,” Human Progress, https://humanprogress.org/dwline?p=103&c0=64&yf=1985&yl=2016&high=1; and “Average Age of Women at First Marriage.”

137 Saidur Rahman Mashreky, Fazlur Rahman, and Aminur Rahman, “Suicide Kills More than 10,000 People Every Year in Bangladesh,” Archives of Suicide Research 17, no. 4 (August 2013): 387–96.

138 Afroze Shahnaz, Christopher Bagley, Padam Simkhada, and Sadia Kadri, “Suicidal Behaviour in Bangladesh: A Scoping Literature Review and a Proposed Public Health Prevention Model,” Journal of Social Sciences 5, no. 7 (July 2017): 254–82.

139 “Suicide Mortality Rate (per 100,000 Population),” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.SUIC.P5?locations=BD.

140 Quoted in Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 175.

141 Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 92.

142 Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 142.

143 Paul Ratje, “Domestic Violence in Bangladesh — in Pictures,” The Guardian, March 15, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/gallery/2016/mar/15/domestic-violence-in-bangladesh-in-pictures.

144 Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 128.

145 Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 185.

146 Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 172.

147 Quoted in Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 171.

148 Kabeer, The Power to Choose, p. 185.